I finally found the time to catch up with the recordings of the MoneyLab conference weekly stream of panels, conversations and presentations. MoneyLab, an event usually held in Amsterdam, gives the stage to critical thinkers, artists, researchers, activists and tech-enthusiasts in search of other economies and financial discourses for a fair society. This year, Aksioma held an extra edition of the event in Ljubljana. I was watching the video recordings one after the other, learning something new and interesting from each of them. And then I reached episode 6: Tax Havens: Normalized Grand Theft. That one was so engrossing and informative that i started to scribble snippets of the conversation. The frantic writing quickly turned into a blog post. Obviously, I’d recommend you stop here and watch the video. Come back if you fancy a (slightly!) more condensed version of the exchange, plenty of links and a few photos.

Tax Havens: Normalized Grand Theft

For this dive into new forms of financial delinquency, investigative artists were talking to Anuška Delić, an investigative journalist and the founder of Oštro, Center for Investigative Journalism in the Adriatic Region. As for the artists they were the Demystification Committee who set up their own global corporate structure with offshore ambitions and RYBN.ORG who make it possible for members of the public to explore the physical and mundane dimensions of offshore finance in their own neighbourhoods.

Delić explained how difficult it is to write about tax haven. Members of the media often believe that the public will find the issue too complex to understand, that they’ll dismiss the problem as just another form of tax optimisation or as a tedious issue that doesn’t concern them. Many of the industries running this planet are based on tax havens, transnational crime relies on them, even politically exposed people use them. It feels like the whole tax haven network is “too big to fail.” Tax havens are often supported by a web of services (legal services, company registration offices, etc.) that not only normalises tax havens but also widens the conceptual gap between the public and the problem. The consequences of tax havens, however, are real and far-reaching for each of us: millions of euros evaporate and never contribute to public services, healthcare and a country’s budget.

Even some of the transparency mechanisms put into place after the scandal of the Panama Papers are often little more than rubber stamps that further obfuscate the tax evader behind a simulacrum of transparency. COVID-19 has brought to light how companies in many EU countries are benefiting from the effects of the pandemic, selling goods to governments, receiving help from governments, offshore companies popping up everywhere. Some countries are trying to curb the phenomenon by making a list of the tax havens. If a company is linked to one of the tax havens on the list, it is not eligible for COVID-19 government financial assistance. However, as Delić added, the European tax havens are not on that list. Which, again, is normalising the problem.

Can art expose and disrupt these mechanisms? Can it contribute to the public debate? That’s what RYBN and the Demystification Committee set up to do:

Demystification Committee, Offshore Spring/Summer 2018

Demystification Committee, Offshore Investigation Vehicle, 2017-2018

The Demystification Committee is a group of artists whose work “studies the intensities of late capitalism, engaging with its networks, interfaces and excesses.”

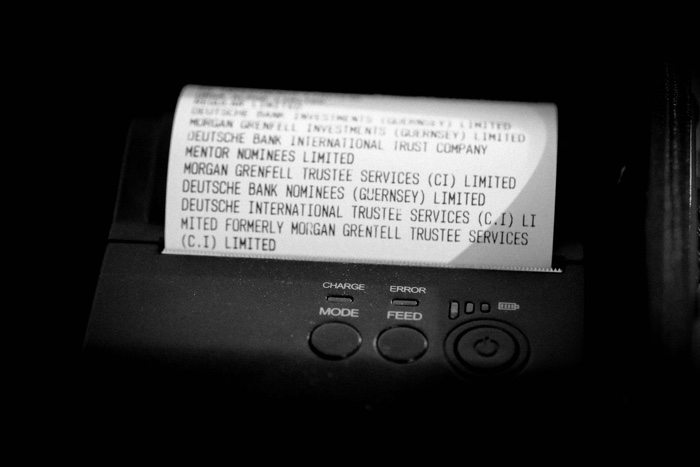

The Offshore Investigation Vehicle, on view at Aksioma until a few days ago, was a small but functional international corporation structure they set up to explore offshore practices from the inside, by directly engaging with the service providers and other actors across a number of tax havens.

The “vehicle” consisted of a company in the UK, a company in the Seychelles and a bank account in Puerto Rico. The artists were the official directors of the UK company. Once it was set up, they ran a series of focus groups and performances to explore different uses of it. Members of the public were also offered the possibility to become shareholders of The Offshore Investigation Vehicle. 53 people joined in. At the first general meeting, the shareholders and the Demystification Committee agreed to initiate two operations: set up a tax avoidance scheme through the online sale of a collection of beachwear (a reference to the visual tropes of offshore practices) and launch The Offshore Economist, a digital publication focusing on the tricks involved in the practice of offshore corporate finance.

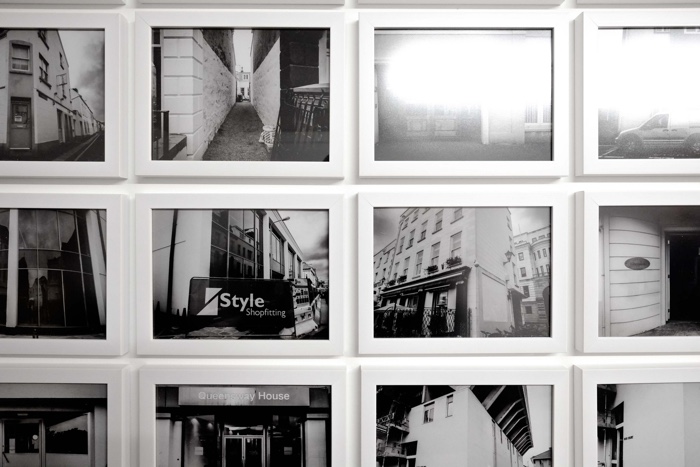

Demystification Committee, Offshore Matters. Exhibition at Aksioma Project Space. Photo: Domen Pal / Aksioma

Demystification Committee, Offshore Matters. Exhibition at Aksioma Project Space. Photo: Domen Pal / Aksioma

Demystification Committee, Offshore Matters. Exhibition at Aksioma Project Space. Photo: Domen Pal / Aksioma

The project played with aspects of the otherwise inaccessible world of offshore corporate finance in order to challenge the narrow tax justice discussion and the usual imaginary of offshore finance.

As the artists had a small budget for the project, they could not afford to hire a law firm to help them set up the company. Instead, their main “consultancy” was the OffshoreCorpTalk forum where they found a provider that offered a cheap combination of offshore company and bank account. The first documents the artists received from the provider contained a number of spelling mistakes, an incorrect address and other errors. It turned out that issuing certificates with errors is standard practice, it’s a precaution to protect the actors involved.

They gave the example of Arron Banks. During an investigation related to Cambridge Analytica, the founder of Leave EU was questioned about the multiple versions of his name appearing in legal documents. He claimed that the misspellings and wrong names were a matter of simple mistakes. It was just a bit sloppy.

The Demystification Committee wanted to explore the scope of making these mistakes…

In order to have credit cards they could use to operate their offshore activity, the artists opened a company bank account in Puerto Rico. They took advantage of the confusion between minuscule L and capital I in Helvetica and wrote their names Francesco TachLmL and OlLver SmLth on the documents. They assumed that there would be some checks and basic forms of validation but the bank sent them bank cards were their names were spelt Francesco TachLmL and OlLver SmLth instead of Oliver Smith and Francesco Tacchini.

Demystification Committee, Offshore Investigation Vehicle, 2017-2018

In the documents submitted to Companies House (the UK’s registrar of companies), they explained that they would be using various loopholes to minimise the payment of their taxes. The artists wanted to see how the official organisation would react to that admission. Companies House wrote back saying they were unable to accept their documents. Ironically, the reason for the refusal had nothing to do with the content of the letter. Company House had simply found that the text was not legible enough. DC resubmitted the same document, this time with more legible text and the registrar accepted it. No question asked.

The whole offshore operation cost the artists a grand total of 2000 euros.

The DC also published a hardcover book that documents the process of setting up The Offshore Investigation Vehicle. The volume is accessible online.

RYBN, The Great Offshore, Basel, 2018

RYBN, The Great Offshore: Offshore Tour in Marseille

The second collective invited to share their investigation into offshore finance was RYBN.ORG. Their extra-disciplinary investigations explore the complex relationships between technologies and economics. RYBN’s talk focused on The Great Offshore, an ongoing inquiry into offshore banking networks and the offshore phenomenon.

The project started as a field investigation. The first step was to make a list of notable tax heavens to visit: The City of London, Jersey and Guernsey, Dublin, Switzerland, Lichtenstein, Bahamas, Caymans, Delaware, Malta, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Singapore and Hong Kong, maybe Jakarta.

RYBN then built an open source situationist prototype to conduct their research: the Offshore Tour Operator, a portable GPS fuelled by the offshore leaks data. Armed with this tool, they (and anyone who participates to their workshops) visit the physical locations associated with leaks in order to confront them with the database and visualise what offshore activity looks like from the ground.

The project adopts several forms. I’m particularly fond of the Offshore Encyclopedia, an online index of the singular manifestation of offshore banking. Its folklore, narratives, figures, companies, icons, etc.

Other related phenomena that the project investigates include golden passports, seasteading, Freeport and other transformations of the art market, the Luxembourg space resources program and other space extractivist initiatives popping all over the world and the Virtual Financial Assets, the rebranding of cryptocurrencies within the institutional spheres, etc. There’s a book in preparation and i can’t wait to get my hands on a copy!

RYBN, The Great Offshore, Basel, 2018

RYBN, The Great Offshore, Basel, 2018

The findings of RYBN research have examined 3 assumptions about offshore practices:

First assumption: Offshore = secret

Since the 2008 crisis, many studies, articles and books have cast aside the veil of secrecy around offshore practices. RYBN mentioned books such as Offshore: Tax Havens and the Rule of Global Crime by Alain Deneault, Treasure Islands: Tax Havens and the Men who Stole the World by Nicholas Shaxson and The Hidden Wealth of Nations: The Scourge of Tax Havens by Gabriel Zucman.

Various scandals, affairs and trials have also played a role in making the problem more conspicuous: the US vs UBS in 2009, the Wildenstein trials in 2017, the Cahuzac affair in France, Europe vs Apple in 2016, etc. Leaks and whistleblowing have brought further scrutiny: Bradley Birkenfeld (UBS), Rudolf Elmer (Julius Bär), Stéphanie Gibaud (UBS), the Offshore leaks in 2013, the Lux leaks, Swiss leaks, Panama Papers, Malta Files, Paradise Papers, Daphne Caruana Galizia‘s investigation, the Daphne project and many more.

A number of art projects have further contributed to exposing the problem: Taxodus and Liquid Citizenship by Femke Herregraven, Citizen Ex by James Bridle, Loophole for All by Paolo Cirio, Duty Free Art by Hito Steyerl, etc.

From all these leaks, works and reports, the public has learnt who the architects of the offshore banking are: UBS, Crédit Suisse, Société Générale, BNP, Deutsche Bank, KPMG, PwC, Deloitte, Ernst & Young. We’ve also learnt the identity of the beneficiaries: Amazon, Apple, Fiat, Google, Microsoft, Netflix, Donald Trump, Starbucks, etc.

Offshore banking is not a marginal, secret system. It is at the heart of global capitalism.

Second assumption: Offshore = elsewhere

There is a gap between the phenomenon and its representation fuelled by the colonial imaginary. The word “offshore” evokes images of palm trees and beaches. RYBN see it as their job as artists to close this gap of representation and challenge the way we represent the offshore phenomenon. As their Offshore Tour Operator workshops and exercises demonstrate, illegal offshore “optimisation” is also rooted in the streets of Basel, Berlin, Amsterdam, Brussels, etc.

Third assumption: Offshore = complex

RYBN quoted a passage from Gabriel Zucman‘s introductory text of The Hidden Wealth of Nations:

“If we believe most of the commentators, the financial arrangements among tax havens rival one another in their complexity. In the face of such virtuosity, citizens are helpless, nation-states are powerless, even the experts are overpowered. So the general conclusion is that any approach to change is impossible.

In reality, the arrangements made by bankers and accountants, shown in the pages that follow, are often quite simple. Some have been functioning unchanged for close to a century.”

RYBN agree with the economist. For them, the model is fairly simple, it’s a matter of adding layer upon layer of obfuscation. Some models of tax avoidance are well documented too: there’s the Dutch Sandwich, the Double Irish, the Singapore Sling, the Bermuda Black Hole, etc.

Offshore is “the new normal”. RYBN believes that offshore is an embodiment of neo-illiberalism, a regime working from the offshore structure and transforming into something that is not neoliberalism but has become much worse.

Notes from the Q&A that followed the discussion:

Maruša Babnik, a corporate tax advocate, observed that when we report on these practices we also unintentionally promote them. Secret tax deals increased dramatically in Luxembourg after the Luxleaks scandal broke.

Lawyer and cryptocurrency specialist Žiga Perovič asked about the technical side of the problem and how much technology is making it easier and cheaper to set up a tax evasion scheme. RYBN answered that there are patents for automatic systems of tax avoidance which were, ironically, validated by various state institutions. They also explained how some companies like KPMG and E&Y hijack the blockchain and sell it as a solution for future greater transparency when in fact they are using blockchain technology against its initial purpose, deepening opacity and paying no mind to public social good. The links between technology and banking are made even more tangible at the Museum of Business History and Technology in Delaware there is a museum of Technique in business.

I’ll close this report with The Spider’s Web: Britain’s Second Empire, a documentary recommended by the Demystification Committee during the exchanges:

The Spider’s Web: Britain’s Second Empire, 2017

Previously: Staying Alive. A “wunderkammer” of disaster solutions, César Escudero Andaluz. So many ways to mess up with surveillance capitalism, Offshore tour operators, lithium landscapes and other things i discovered at MUTEK_IMG, Economia, a festival on economy without the economists, Flash crashes. Glitches in the trading system, Dataghost 2. The kabbalistic computational machine, etc.

Check out also ML8: Offshoring and Other Magic Tricks of Global Finance – An Interview with RYBN.