DISNOVATION.ORG, Shanzhai Archeology, 2017. Exhibition view at FAKE: THE REAL DEAL?. Photo credits: Science Gallery Dublin

Matt Kenyon, Giant Pool of Money, 2016. Exhibition view at FAKE: THE REAL DEAL?. Photo credits: Science Gallery Dublin

FAKE: The Real Deal?, a free exhibition at Science Gallery Dublin, invites us to leave behind our prejudices when considering the simulated, the artificial and the fictitious.

“Fake” is a word that pops up ad nauseam in social, political and economic contexts. It is often associated with low quality goods, forged artworks, earnings of dubious origins, polite orgasms, Trump bombastic ‘rhetoric’ (or rather lack thereof), etc.

The curators of the exhibition, however, challenge us to spend time examining the multiple facets of the fake and to reconsider any assumption we might have about it:

From fake meat to fake emotions, if faking it gets the job done, who cares? In both the natural world and human society, faking, mimicking and copying can be a reliable strategy for success. When the focus is on how things appear, a fake may be just as valuable as the real thing. But what about replicating taste, emotions, chemical signatures, facts and trademarks? Have patents, politics, and art given copying a bad name? From biomimicry to forged documents, from scandals to substitutes, Fake asks when authenticity is essential, when copying is cool, and what the boundary is between a fakery faux-pas and a really fantastic Fake.

FAKE is your typical Science Gallery Dublin exhibition. It puzzles, informs, puts you out of your comfort zone at least once and it entertains you in the process.

Many of the dimensions of the fake are analysed and discussed in the show but the one that ended up staying with me after i had left Dublin looked at the ruses and strategies deployed by animals and plants to deceive each other. In the video recording of a joint talk they gave at the Science Gallery in March, Fiona Newell and Nicola Marples bring to light some of the sneaky tricks used by plants as well as human and non-human animals:

Fiona Newell, Professor of Experimental Psychology and Nicola Marples, Professor in Zoology, Trinity College Dublin talking about deception in the natural world

The presentation is absolutely fascinating. The superstar among all those creatures of treachery is not the human being but the mimic octopus, a species of octopus capable of impersonating other local species:

Mimic Octopus: Master of Disguise

Let’s remain in the company of cephalopods and dive into the exhibition itself:

Ryuta Nakajima, Cuttle 61

Like other cephalopods, cuttlefish are masters of shape and shade shifting when they need to camouflage themselves in the background. Ryuta Nakajima attempted to push the cognitive and interpretive system of cuttlefish camouflage patterns to their limits by decorating aquaria with computer-generated images of famous visual artworks. His installations shows how the creatures responded to art reproductions. The conclusion of the artistic experiment is probably that the cuttlefish didn’t see the artworks as worthy of any mimicking effort.

Barrett Klein with Joey Stein, Paul Clements, Ryan Taylor, Faux Frogs. Research models of calling male frogs, 2005—2018

Barrett Klein with Joey Stein, Paul Clements, Ryan Taylor, Faux Frogs. Research models of calling male frogs, 2005—2018. Exhibition view at FAKE: THE REAL DEAL?. Photo credits: Science Gallery Dublin

Robotic Frog Attracting Potential Mate. In the video a female tungara frog approaches a robofrog inflating its vocal sac. The female can also hear recorded mating calls playing

Ecologists can also deploy deceptive strategies when studying animal species.

Science collaborators Ryan Taylor and Michael Ryan were studying the túngara frogs in Panama and they wanted to understand the connections between multimodal signaling (using more than one sensory cue) and mate selection. Behaviourist Barrett Klein built ‘faux frogs’ (a.k.a. ‘robofrogs’) to assist them in their cheeky field studies. As the video above demonstrates, the artificial amphibians successfully fooled real female túngara frogs. When choosing a potential mate, these ladies listen to the sounds of the male calls but they are also sensitive to the sight of the male frogs inflating their vocal sacs.

Heather Beardsley, Die Sammlung/The Collection, 2017. Exhibition view at FAKE: THE REAL DEAL?. Photo credits: Science Gallery Dublin

Heather Beardsley, Die Sammlung/The Collection, 2017

Heather Beardsley’s collection of decidedly odd creatures proposes that we stop and reflect on the contrasting frameworks of museums and art galleries.

Museums use display conventions developed over time to communicate knowledge to a non-expert audience. These conventions convey the importance of the objects, but do not invite critical thinking. Contemporary art galleries, on the other hand, challenge viewers to think critically about the artifacts and decide whether or not they have any intrinsic value.

Beardsley lined up a series of animal specimens inside antique jars in a museum display. Some are hand-made reproductions of real animals. The others are actual biological creratures.

By installing these specimens together, the artist encourages viewers to question the hierarchical system they are used to and think more critically about museum displays.

Patricia Pisanelli, Stretching Cheese, 2017. Exhibition view at FAKE: THE REAL DEAL?. Photo credits: Science Gallery Dublin

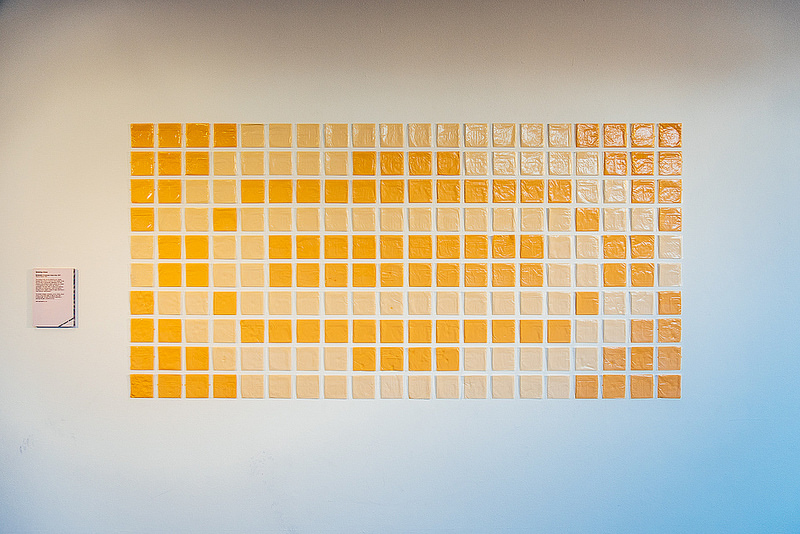

Patricia Pisanelli‘s wall of square slices of processed cheese makes us question the border between fake and authentic. How much fake are you allowed to use in a food product for it to remain authentic? In the case of cheese, the answer is 51%.

Slices of processed cheese are made from cheese (and sometimes other dairy by-product ingredients), emulsifiers, saturated vegetable oils, salt, food colouring, whey or sugar. If the product contains at least 51% cheese, it can be called cheese food. Less than 51% and the slices have to be labelled as “cheese product.”

Because there are so many processes and ingredients that enter into the production of these slices, they end up presenting different flavors, colors and textures. The artist chose slices from different brands. The assemblage is changing gradually over time. The colour of some of the slices is slowly fading under the light. Stains appear on others. Some seem to dry up inside their flimsy plastic wrapping. Others remain defiantly immutable.

James Shaw, Modular Mechanics Hairy Armchair, 2017

James Shaw‘s armchair is a bit maddening. It’s made from both natural and synthetic materials: ash timber, plastic timber, brass, real sheepskin and faux fur. I inspected it with great care and i was unable to distinguish what was organic and what was imitating the organic. Which sums up the reality around us: it’s made of real and fake. They are so intermingled, so good at imitating each other that we struggle to separate one from the other.

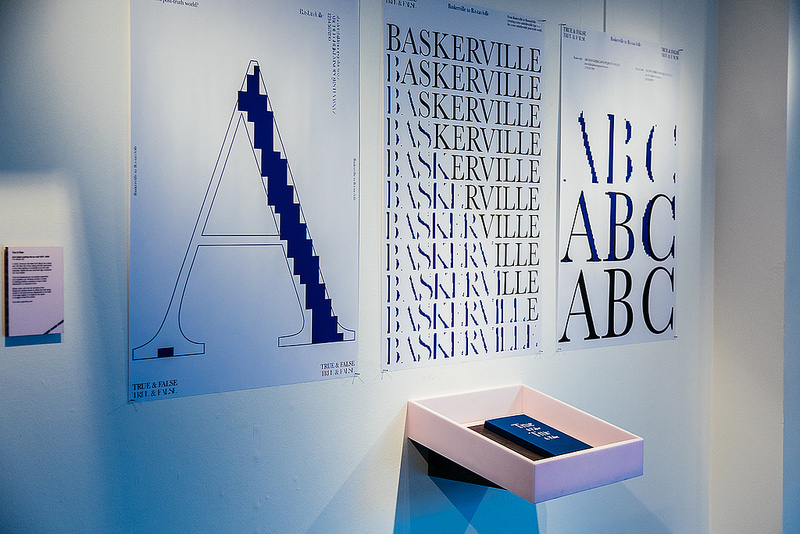

Finn Mullan, True & False, 2017—2018. Exhibition view at FAKE: THE REAL DEAL?. Photo credits: Science Gallery Dublin

Although it doesn’t deal at all with the organic, i need to mention Finn Mullan‘s Bastardville font because it addressed in a very literal and smart way the kind of mental association recent events have caused us to make when we hear the word “Fake.”

The font was inspired by a study that U.S. documentary film director Errol Morris made back in 2013. The research attempted to find out what typeface is considered to be the most believable, the most likely to convince us that a sentence is true. It turned out that Baskerville was considered the most reliable.

Broken down until it becomes barely legible, the Baskerville gradually turns into Bastardville. The battered typeface echoes the truth eroded in the post-truth era. In the Post-Truth age, no typeface, not even the most convincing one, can save the truth from corrosion and decay.

And if you’re curious about how typefaces can shape perception, you might enjoy this episode of Word of Mouth.

More works and installation views from FAKE:

Morten Rockford Ravn, Fear and Loathing in GTA V, 2015 — present. Exhibition view at FAKE: THE REAL DEAL?. Photo credits: Science Gallery Dublin

Morten Rockford Ravn, Fear and Loathing in GTA V, 2015 — present

Morten Rockford Ravn, Fear and Loathing in GTA V, 2015 — present

Janez Janša, Janez Janša and Janez Janša, Janez Janša Bottles, 2017. Exhibition view at FAKE: THE REAL DEAL?. Photo credits: Science Gallery Dublin

DISNOVATION.ORG, Shanzhai Archeology, 2017. Exhibition view at FAKE: THE REAL DEAL?. Photo credits: Science Gallery Dublin

Isaac Monté & Toby Kiers, The Art of Deception, 2015. Exhibition view at FAKE: THE REAL DEAL?. Photo credits: Science Gallery Dublin

Unknown, Fake Fake Alien Autopsy Head, 1996. Exhibition view at FAKE: THE REAL DEAL?. Photo credits: Science Gallery Dublin

Also part of the exhibition: Vapour Meat: a helmet to vape the essence of ‘clean meat’ and The Phylogenetic Atelier: Would your wear clothes made of the skin of de-extinct species?

The exhibition FAKE: The Real Deal? remains open at the Science Gallery at Trinity College Dublin until the 3rd of June 2018.