Very few of us think of trees in terms of how hardworking they are. And yet, they work 24/7 and most of their labour is to our benefit. Trees (and any plant for that matter) perform all kinds of services for us. They shelter us against the elements, they help filter water and cool the air, soak up solar radiation, prevent soil erosion, provide living space for wildlife, can be turned into wood, some of them bear fruit and beautiful flowers, etc. They also perform all sorts of ‘cultural services’ for us: they help us unwind, inspire art, mental well-being and spiritual experiences. All of us, human and non-human alike, benefit from their presence around us.

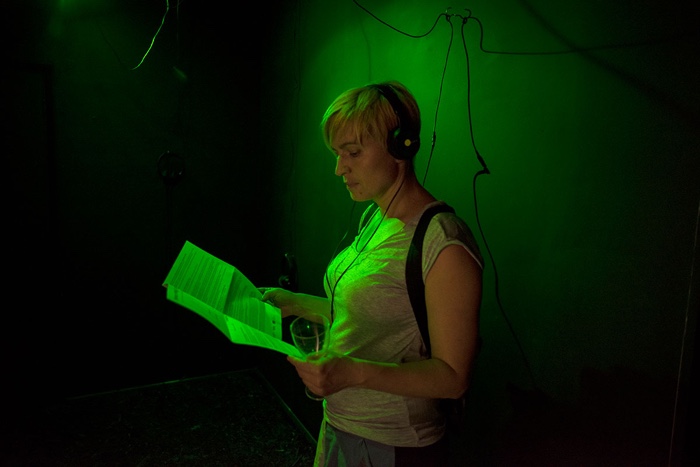

Marija Bozinovska Jones, Treebour, 2018. Photo by Pau Ros

Image courtesy of Marija Bozinovska Jones

Artist Marija Bozinovska Jones pays homage to this ‘treebour’ in her contribution to Playbour – Work, Pleasure, Survival, an exhibition at Furtherfield in London that explores an issue that deserves more attention from us: the blurring between work, well-being and play in an age of increasingly data-driven technologies.

With the sound piece, Bozinovska Jones investigates playbour from the perspective of trees and asks:

What would it mean to value this treebour like we value human labour? Trees’ careers last hundreds of years. They’re also natural co-operators and communicators, existing in symbiotic harmony with each other and other lifeforms. If they ever form a union and strike for back pay we’re in trouble.

If we were more aware of what trees do for us, would we treat them like we treat women doing an unfair share of household chores? Like the YouTubers creating free content, the factory and field workers exposed to hazardous chemicals and the other human workers who don’t get a decent wage for their efforts?

And if we valued the labour that trees perform for us, wouldn’t we be tempted to make them work harder? Would we try and extract profit from the “social” underground and air-borne networking of trees? Would they end up being the new victims of companies like Uber, Deliveroo and Amazon Mechanical Turk that promise autonomy and flexibility but make humans compete for each gig to drive down costs and reframe hobbies as potential revenue streams?

Marija Bozinovska Jones, Treebour promo video

The Treebour sound installation gives a human voice to three treebourers. Each of these anthropomorphised trees patiently describes their worth, highlighting the insidious logic of the gamification of all forms of life and work.

Marija Bozinovska Jones, Treebour, 2018. Photo by Pau Ros

Treebour is a very moving and smart sound piece. I don’t have a video or sound file of the beautiful text of the trees’ pleas but i got in touch with Marija Bozinovska Jones and asked her to tell us more about trees, anthropocentrism and all things playbour:

Hi Marija! Why did you decide to approach the playbour theme through trees? Looking at some of your previous works, i would have expected you to explore playbour through a piece that comments on playbour in virtual environment.

I tend to consider mimicry of biological in computational and social infrastructures.

The early stages of conceptualising the work was collective, during a workshop organised by curator Dani Admiss with Furtherfield. After its conclusion some of us participating were asked to produce work towards an exhibition.

In the course of the workshop we were discussing the unusual gallery location of Furtherfield – in the middle of a park; I am personally keen to exhibit in environments outside the white cube. The first idea was to work with couple of chosen trees surrounding the gallery onto which we would map contemporary socio-cultural values, for example through creating social media profiles for the trees, where they would compete against each other for attention, followers and likes.

Consequently, another workshop participant, Rob Gallagher who is a postdoctoral researcher in Gaming and Identity at King’s College, and myself developed individual monologues for three tree species found in Finsbury park to correspond to human characters. They were to communicate gamified aspects and corporatization of interpersonal relationships online. We likewise aimed to disneyfy the tree personas to appeal to the wide demographic of the audience that passes through the park and the gallery.

Marija Bozinovska Jones, Treebour, 2018. Photo by Pau Ros

The text of Treebour is amazing. It’s moving, very well researched and it made me appreciate trees even more. Perhaps, if we had a better understanding of what trees and other plants do for us we would be less keen on ‘artificializing’ our landscape with roads, airport extensions, shopping malls, etc. Do you think we need to instrumentalize nature more in order to recognise its value? Or are there dangers to that strategy?

Being an anthropocentric society, we have a tendency to translate other natural species’ communication to fit our logic rather than leaving it as something open which transcends our knowledge and perception.

Beyond our own nature, we often tend to take others’ for granted, as something to be consumed, exploited and conquered. In this respect we can learn from trees who live in symbiotic relationships with each other and other life forms.

We have organised ourselves in a way that we are dependent on concrete infrastructural architecture. In urban environments, the ratio of the built and the artificial is highly disproportionate with the natural.

Research studies observe how our wellbeing increases when surrounded with other natural species of flora and fauna, even with downscaled botanical versions such as plants in our living and working environments; the sole use of green colour in interior space is supposed to have calming properties for the human nervous system.

Marija Bozinovska Jones, Treebour, 2018. Photo by Pau Ros

Marija Bozinovska Jones, Treebour, 2018. Photo by Pau Ros

Marija Bozinovska Jones, Treebour, 2018. Photo by Pau Ros

I can imagine where you found the information for the techy-intellectual tree and the habitat tree. But what about the “relaxing tree”? How did you manage to make it sound so Gwyneth Paltrow-ish? Where does that particular jargon come from?

The character for the Relaxing (beech) tree was based on ASMR YouTubers. I asked my studio colleague to contribute with his voice for it as he has a very soothing voice.

The monologue was based on guided mindfulness instructions as something I am practicing myself as well as researching for work.

Treebour is clearly the outcome of a research on trees and the role they play in making our planet more liveable for us and other living species, etc. Is there anything you discovered during your research that truly amazed you?

The research was building on previous knowledge, for example of way in which trees communicate with each other as well as other life forms, phrased as ‘wood wide web’ and arboreal ARPANET. Rob came across some descriptive botanical jargon such as ‘vascular cambium’ and ‘carboniferous rhytidome‘.

Marija Bozinovska Jones, Treebour, 2018. Photo by Pau Ros

I love that you made Treebour a sound installation. It’s very suggestive and gives a sense of intimacy. But what were your motivations to do an art piece rather than a video animation or a performance for example? Why did you decide to give trees a voice?

For awhile now, our modes of communication is mediated through blackboxed screen interfaces predominantly employing the visual sense, followed by the haptic and the sonic. Over the past years, I have been examining human voice as a dimensional interface which is able to encapsulate affect. Due to our ability to detect and project emotions onto voice, it is often exploited by technocapitalism through disembodied AI. For example, intelligent personal assistants couple sleek consumer products with a sentient often female voice since we are genetically predisposed to react to a voice most similar to our primary caregiver’s, our mother. Anthropomorphised technologies are something I have been addressing through a proxy MBJ Wetware, a simulation of my voice via machine learning.

What shape does the concept of playbour play in your life as an artist?

Producing ’Treebour’ was a role-play itself.

With the plethora of social media with its potentials to promote work, lifestyle and disseminate opinions, playbour reaches new immaterial labour heights.

Thanks Marija!

Marija Bozinovska Jones’s Treebour is part of Playbour, an exhibition curated by Dani Admiss for Furtherfield Gallery in London. The show remains open until Sunday 19 Aug 2018.

Playbour is realized in the framework of State Machines, a joint project by Aksioma (SI), Drugo more (HR), Furtherfield (UK), Institute of Network Cultures (NL) and NeMe (CY).