Paul Chaney, Breast Plough’o’metric, 2014. Photo via THG (Thelma Hulbert Gallery)

Scientist, curator and philosopher Sue Spaid coined the term ‘Ecovention’ in 1999 and went on to illustrate its meaning and reach three years later with an exhibition titled Ecovention: Current Art to Transform Ecologies at the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati. Spaid defines ecoventions as inventive, practical actions with ecological intent. The focus of an ecovention is not to interfere aesthetically with the landscape but to explore how art can contribute, even on a microscale, to the improvement of a given ecosystem.

This year, Sue Spaid teamed up with Roel Arkesteijn to look at the development of these artistic ecological interventions in Europe. Together, they curated Ecovention Europe: Art to Transform Ecologies, 1957-2017 at De Domijnen in Sittard.

The artists in the show not only remind us that the way we exploit the earth and its resources is irresponsible and unsustainable but they also look for solutions to environmental destruction. Alone or with the help of local communities, they’ve cleaned up polluted soils, planted wheat fields, provided pollinators with appetizing flowery landscapes, built hanging gardens, initiated edible and medicinal urban farms, developed schemes for sharing excess food and bred more resilient chicken breeds.

Unlike the website of De Domijnen, the show is in both Dutch and English. It is also very good. Informative, impeccably researched and uplifting. Ecovention Europe cheered me up and convinced me that the human animal is not a hopelessly toxic species after all.

Cecylia Malik, Białka’s Braids, 2013/2017. Photo credit: Mieszko Stanisławski

Do me a favour and visit the show if you live in the area (Sittard is 15 minutes away from Maastricht by cheap and cheerful train) because exhibitions like these are few and far between. Sue Spaid explains why in this extract from a fascinating interview she had with Metropolis: Pragmatically speaking, this kind of art is a nightmare for institutions. They prefer the kind that comes in a box, comes out of a box and then gets returned in a box a few months later. If the artists decide to exhibit something living, the museums are responsible for keeping it alive! If it is living, it might generate insects, dust, vapor, etc. Then there is the issue of commissioning ecoventions, which is another thorny issue, since it demands artists working with politicians, scientists, community members, etc., not to mention securing permits to place the work.

The exhibition is huge, with dozens of art works, all of which i’d like to mention. I’ll only cover a fraction of what i’ve discovered at De Domijnen in this article and the one coming up tomorrow (if i have good wifi access during my 9 hour long journey and i’m not too lazy) or on Wednesday. Here’s a first selection:

Paul Chaney, Breast Plough’o’metric, 2014 (video)

Paul Chaney, Slug’o’metric Device II, 2008

Paul Chaney, Slug’o’metric Devices

Paul Chaney. Installation view at Museum De Domijnen. Photo by Bert Janssen

Made of forged iron and chestnut, Breast Plough’o’metric is a replica of an ancient breast plough. Paul Chaney outfitted it with digital strain gauges and a small computer to record the exact amount of effort needed to plough a given tract of land by human power alone.

The instrument is part of a series that explores the metrics of direct human interaction with the land. A previous work, the Slug’o’metric series of kinetic sculptures employs progressively more complex technologies to kill and count slugs in your garden patch. The more technologically sophisticated each device gets, the more it removes the user from the physical action of killing the mollusc. Both the Slug’o’metric series and the Breast Plough’o’metric unsettle the typical illusion that ‘living with the land’ is a pure and uncomplicated affair.

George Steinmann, Blues for the glaciers, 2015. Photo: Tabea Reusser

In 2015, artist and blues musician George Steinmann became the first ever official “artistic observer” at the World Climate Conference COP21 in Paris.

It’s in this context that Steinmann recorded a concert of blues music in the Glacier du Rhône, in the Swiss Alps. He chose this particular glacier as the venue for the performance because the ice up there is melting about 8 cm a day. It’s global warming in action and without any veil of modesty.

The concert was filmed and unfiltered with all the sounds of nature

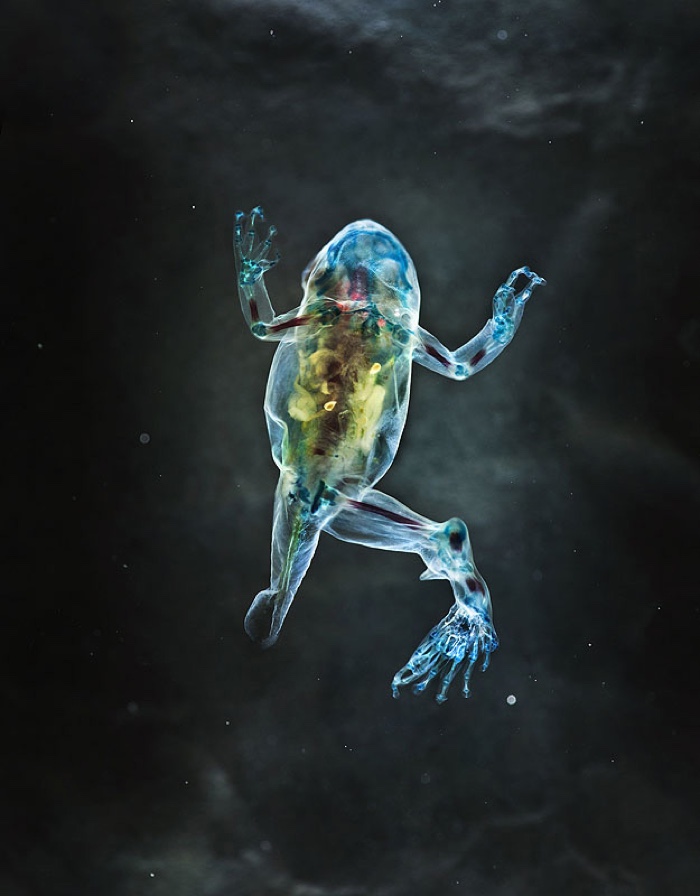

Brandon Ballengée, DFA136: Procrustes, cleared and stained Pacific tree frog collected in Aptos, California in scientific collaboration with Stanley K. Sessions (from the series Malamp Reliquaries), 2013

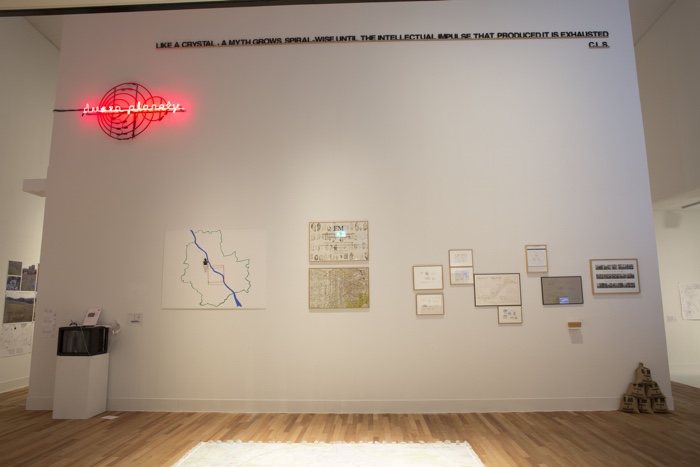

Installation view of Ecoventionat Museum De Domijnen, September 2017. Photo by Bert Janssen

Malamp Reliquaries are a series of portraits of severely deformed amphibians that artist and biologist Brandon Ballengée has discovered in wetlands, ponds and rivers around the world. Their extra or missing limbs can be explained either by the presence of chemical pollutants or by a parasite, Ribeiroia ondatrae. It is thought that the parasite disrupts the cells involved in the limb bud formation of tadpoles.

To make these portraits, the artist chemically “cleared and stained” the frogs. The photos are printed as unique watercolor ink prints and each individual frog appears to “float” in clouds. This otherworldly quality is reinforced by the titles named after ancient characters from Greco-Roman mythology.

The artist writes: They are scaled so the frogs appear approximately the size of a human toddler, in an attempt to invoke empathy in the viewer instead of detachment or fear: if they are too small they will dismissed but if they are too large they will become monsters. Each finished artwork is unique and never editioned, to recall the individual animal and become a reliquary to a short-lived non-human life.

AnneMarie Maes, Transparent Beehive, 2013-2014. Photo by AnneMarie Maes

AnneMarie Maes, Red Flag. Photo by AnneMarie Maes

The Transparent Beehive is an observation beehive that used to home a living bee colony. The beehive is fitted with microphones which pick up the vibrations and sounds of the hive and monitor the colony. Cameras inside the hive survey the growth of the wax structures and the activity of bees. Additional sensors measure the microclimate inside the structure. Data is then processed and visualized to make the state of the colony tangible.

In 2013, the bees inhabiting Maes’ beehive suffered colony collapse disorder due to the invasion of the waxmoth. Standing empty, emitting only the recorded sounds of the honey bees that once inhabited it, the work bears witness to colony collapse disorder that challenges our food future.

In the exhibition, the beehive is accompanied by a lightbox depicting a scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of a honey bee’s extended glossa, the hairy “tongue” in the bee’s mouth that collects nectar from flowers.

Finally, the Red Flag, a biotextile grown by microorganisms, warns us that we should act to preserve (or restore) the well being of our environment.

Vera Thaens, Lost Common Sense, 2014/2017, Black lights, broccoli, Monsanto broccoli seed patent

Vera Thaens, Lost Common Sense, 2014/2017. Installation view at Museum De Domijnen. Photo by Bert Janssen

Vera Thaens hid an illicit plantation of broccoli under the staircase of the museum. The work, called Lost Common Sense, reacts to Monsanto being granted a patent on broccoli in all of its natural forms in Europe (in EUROPE!!!)

I’ll mention Thaens again in my upcoming story. I wish i could find more documentation about her work online. That lady is my new hero!

Lara Almarcegui, Mineral Rights, Tveitvangen, 2015

Lara Almarcegui looked into issues surrounding the ownership of the ground and the depths beneath it. Mineral Rights are regulated differently from country to country. They entitle an individual or organization to explore the rocks, minerals oil and gas found below the surface of the land. It is often impossible for a private individual to acquire them. After a lengthy procedure, Lara Almarcegui gained the mineral rights to the iron ore deposits for an area of one square kilometer in Tveitvangen, near Oslo. The mineral rights reach from the subsoil down to the center of the earth. Her objective though was to prevent the resources from being extracted.

She later acquired another iron deposit in Buchkogel and Thal, near Graz.

The artist writes: The project reminds us of how the territory is shaped at a geological level and how it is broken down and split into pieces for mine exploitation. While presenting what is below the feet in our contemporary cities and who owns it, the project raises the question of mineral extraction for the production of construction materials and it brings to light questions on land ownership and resources ownership.

Federica Di Carlo, Come in terro cosi in cielo (As in earth, so on heaven), 2013-ongoing

Federica Di Carlo, Come in terro cosi in cielo (As in earth, so on heaven), 2013-ongoing

Since Federica Di Carlo noticed that not all rainbows have all 6 colours, she has been working with scientists to discover the relationship between incomplete rainbows and air pollution.

Installation view of Ecoventionat Museum De Domijnen, September 2017. Photo by Bert Janssen

Czekalska + Golec, Homo Anubium (St. Francis 100% Sculpture), 1680-1985

Tatiana Czekalska and Leszek Golec co-created these artworks (originally church sculptures) with woodworms that had eaten so much of the material that their former owners deemed them useless as religious sculptures. The artists however saw the aesthetic and intrinsic value in the contribution of the animals, in particular their having selected Francis of Assisi, patron saint of animals and the natural environment. The artists date it 1680-1985 as they see the creative process as being conducted over centuries

More views from the exhibition:

Installation view of Ecoventionat Museum De Domijnen, September 2017. Photo by Bert Janssen

Installation view of Ecoventionat Museum De Domijnen, September 2017. Photo by Bert Janssen

Installation view of Ecoventionat Museum De Domijnen, September 2017. Photo by Bert Janssen

Installation view of Ecoventionat Museum De Domijnen, September 2017. Photo by Bert Janssen

Installation view of Ecoventionat Museum De Domijnen, September 2017. Photo by Bert Janssen

Installation view of Ecoventionat Museum De Domijnen, September 2017

The publication that accompanies the exhibition is a fantastic resource for anyone interested in ecological art. You can get it online at BOL if you live in The Netherlands. The rest of us can buy it on Amazon.

Ecovention Europe, art to transform ecologies, 1957 – 2017 remains open at Museum Hedendaagse Kunst De Domijnen in Sittard (NL) 7th January 2018