The past 2 decades have seen an acceleration of the horrendous and the uncontrollable: wars, pandemics, financial crashes, scarcity of energy resources, climate crisis, rise of dangerous ideologies and distrust in facts, etc. If today’s world looks uncertain, tomorrow appears to be even more daunting. Unknown Unknowns, the 23rd edition of the Triennale in Milan is looking at what we don’t know that we don’t know. And it does so by using art, design and sciences to help us confront -and even revel in- the uncharted that scares us.

Antonio Fiorentino, Dominium Melancholiae, 2014

Unknown Unknowns. An introduction to mysteries. Exhibition view. Photo: DSL Studio

The exhibition’s full title is Unknown Unknowns. An Introduction to Mysteries. I love its ambiguity. While the show is curated by astrophysicist Ersilia Vaudo Scarpetta from ESA and looks at scientific realities such as gravity or mathematics, the word “mysteries” gives it a more spiritual aura, suggesting perhaps that we will emerge the exhibition as “initiated members.”

One of the main anchors of the show is that we only know 5% of the observable universe. Perhaps even less than that. I love this humbling admission that scientists, designers and artists alike have more questions than answers. The show, however, attempts to equip us with ideas and prototypes that could make this unknown unknown more “manageable”: tools to inhabit outer space, augment human senses, print body parts, make our knowledge of cosmic concepts easier to understand by all, etc. I’m more dubious about the exhibition’s ambition that it might help us overturn our anthropocentric vision of the world and our imperialistic urge to tame the unknown. I’ve heard that one so often over the past few years, I’m wondering if anyone still pays attention to that kind of claim.

Momoko Seto, Planet Σ, 2014

Momoko Seto, Planet Σ, 2014

Visitors of the show will find that the technological often contends with the artistic when it comes to creating aesthetics and ideas that stop them in their tracks. Recent images captured by the James Webb space telescope have made that very clear.

Here are some of the ideas and works I found most fascinating during my visit of Unknown Unknowns:

Unknown Unknowns. An introduction to mysteries. Exhibition view. Photo: Gianbellomo for Elle

Adam Elsheimer, The Flight into Egypt, 1609

The show opens with a reproduction of Adam Elsheimer’s The Flight into Egypt, a Biblical scene that is considered to feature the first realistic depiction of the night sky, with the Milky Way represented as a myriad of individual stars accurately distributed in the constellations of Ursa Major (the Great Bear, Big Dipper and Plough) and of Leo.

On a side note, there’s an appealing show at the Prado Museum looking at how art has represented the cosmos in the past.

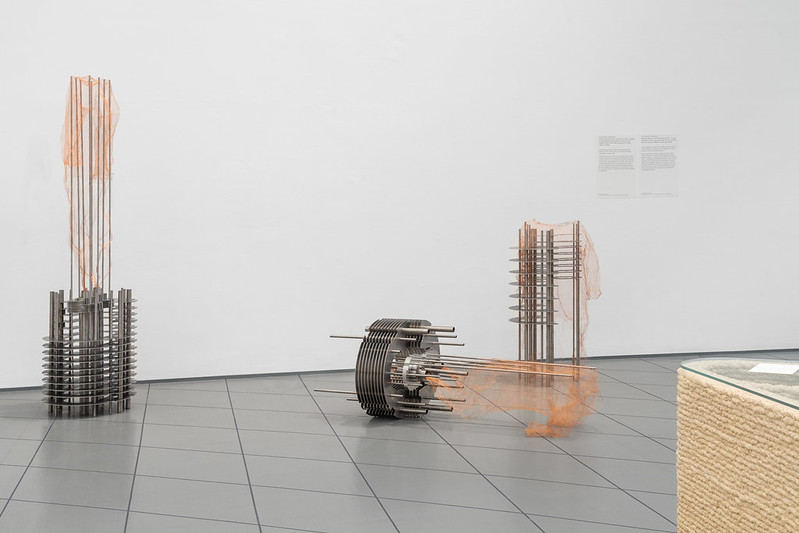

Julijonas Urbonas, When Accelerators Turn into Sweaters, 2016-ongoing. Photo by Aistė Valiūtė and Daumantas Plechavičius

Julijonas Urbonas, When Accelerators Turn into Sweaters, 2016-ongoing. Photo by Aistė Valiūtė and Daumantas Plechavičius

Julijonas Urbonas, When Accelerators Turn into Sweaters, 2016-ongoing. Exhibition view. Photo: DSL Studio

During a residency at the CERN centre, Julijonas Urbonas investigated the unique properties and imaginary qualities of superconductors, used in particle accelerators to generate large continuous electric and magnetic fields for beam acceleration and manipulation. Urbonas was particularly interested in quantum magnetic levitation, a phenomenon that occurs when scientists use the properties of quantum physics to levitate an object (specifically, a superconductor at its critical temperature) over a magnetic source (a quantum levitation track designed for this purpose).

The artist explored the impact that levitation would have on art, design and architecture if this event were possible at room temperature. ‘What if your clothes, for example, were made of this levitating stuff? Maybe such a levitating wearable could bring particle physics into the experiential realm: the micro into the macro?’

The artist started experimenting with knitting superconductor fibres immersed underwater – non-coated superconductors can ignite under oxygen exposure – and looking into cryogenics to make them levitate.

Urbonas created a full-scale stainless steel replica of a section from the Large Hadron Collider and developed a way to weave superconducting fibres into textiles. The cables knit together to create a kind of sweater and levitate in response to the magnetic field.

The work, titled, When Accelerators Turn into Sweaters, is part of Urbonas’ study of gravitational aesthetics, a term he coined to describe an art and design approach that exploits the means of manipulating gravity to create experiences that push the body and imagination to the extremes.

Alicja Kwade, Selbstporträt / Self-portrait, 2021. Photo: Roman März

Alicja Kwade broke down the body into the purely elemental by presenting it in 24 small vials containing the chemical elements that make up the human anatomy: oxygen (O), carbon (C), hydrogen (H), nitrogen (N), calcium ( Ca), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), sulphur (S), sodium (Na), chlorine (Cl), magnesium (Mg), iron (Fe), fluorine (F), zinc (Zn), silicon (Si), bromine( Br), copper (Cu), selenium (Se), manganese (Mn), iodine (I), nickel (Ni), molybdenum (Mo), chromium (Cr), cobalt (Co).

Her artistic investigation of the self echoes the complexities of understanding what it means to exist. We all share these chemical elements and yet, once mixed together to form a body, they give strikingly different outcomes.

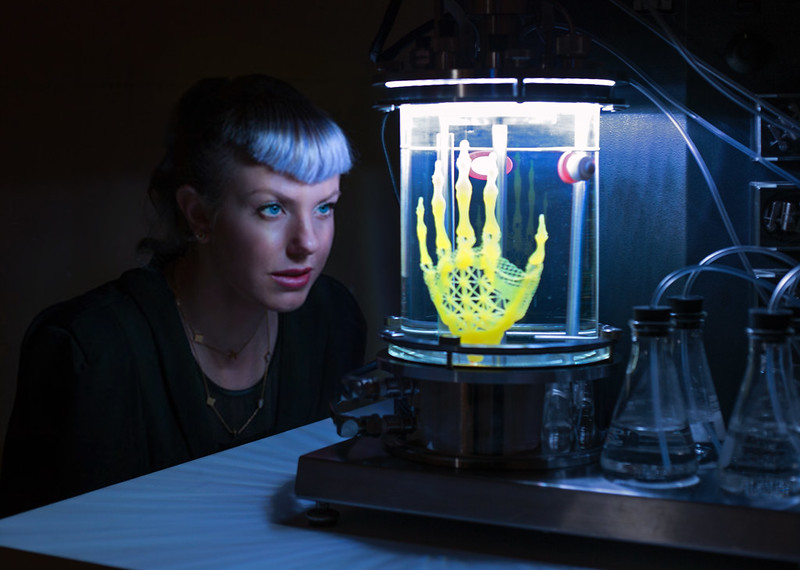

Amy Karle, Regenerative Reliquary, 2016. Photo: Ars Electronica Vanessa Graf

Amy Karle grew bone on a bioprinted scaffold in the shape of a human hand. Made of biodegradable hydrogel, the scaffold eventually disintegrates allowing the human Mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs from an adult donor) seeded onto the design to grow tissue and mineralise into bone.

The sculpture is kept inside a glass bioreactor, in reference to the practice of using reliquaries to contain the purported or actual remains of religious figures. Instead of enshrining the inanimate remains left after death, the Regenerative Reliquary looks at future bodies by suggesting the possibility of growing living body parts. In the perspective the Milan exhibition, the work suggests a future when we will be able to use 3D printing to “fix” the first humans on Mars. It also investigates who we could become if we exploit the full potential of biotechnologies.

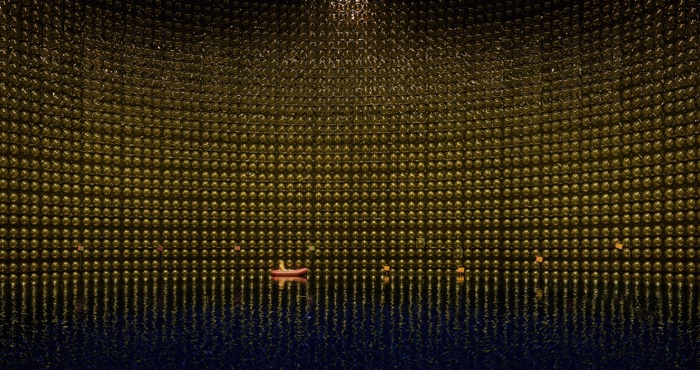

Jan Hosan, Super Kamiokande, 2018. Courtesy of the artist

Neutrinos are sub-atomic particles that travel the universe and pass through matter (including our bodies) all the time. Studying these particles helps scientists detect dying stars and understand why the Universe has so much more matter than antimatter.

Spotting neutrinos requires special detectors. The largest of its kind, the Kamioka Observatory, is buried under a mountain in Hida, in Gifu Prefecture, Japan. The steel tank with a diameter of 39.3 meters and a height of 41.4 meters is located deep underground – in order to be exposed to as little cosmic radiation as possible. The walls are lined with thousands of highly sensitive light detectors that look like golden bulbs. They can identify the tiniest amounts of light produced by the passage of the neutrinos in their interactions with water. Which is a very very rare event.

In 1987, the Kamiokande detector caught the first neutrinos from a supernova. A dozen neutrinos came from supernova 1987A, which occurred in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a small galaxy that orbits the Milky Way.

Jan Michael Hosan was one of the very few photographers allowed to take pictures inside the giant gold chamber of the Super-Kamiokande when the neutrino detector had to be reopened for maintenance work. The photo of the Kamioka Observatory is gigantic and mesmerising. In the image above you can just about see an orange dinghy that floats on the surface of the water.

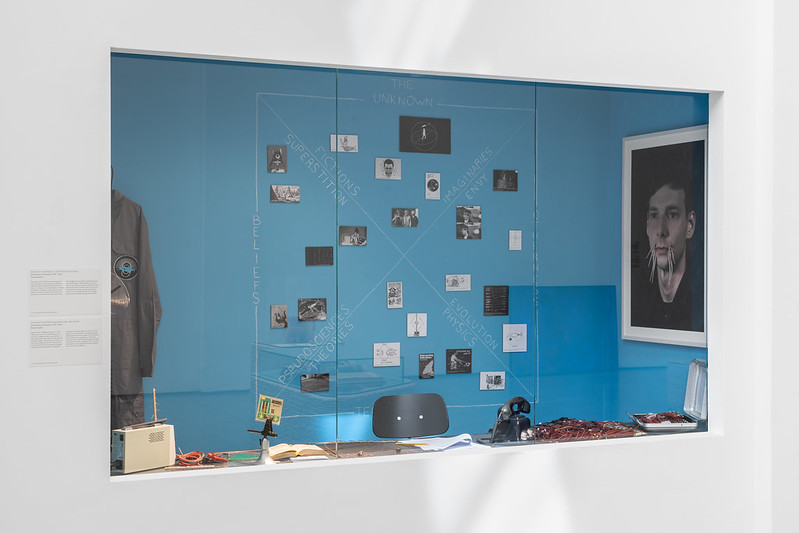

Susanna Hertrich and Shintaro Miyazaki, Sensorium of Animals, 2016–2019. Exhibition view. Photo: DSL Studio

Designer Susanna Hertrich and researcher Shintaro Miyazaki explored the possibility of expanding the human sensory apparatus and enhancing it with sensorial abilities similar to those found in elephant nose fish. The species can navigate and find prey in the murkiest rivers by emitting brief pulses of electricity. It also relies on a passive system attuned to the minute electric signatures of everything living in its environment. Hertrich and Miyazaki wondered if it would be possible to engineer a similar EM sense for the human sensory apparatus.

The installation offers insight into a research process that normally remains hidden. Books, electronic prototypes, images deriving from the research process, a desk and a chair, inspiring works, tools and curious items are displayed inside a “research aquarium”.

The project also has a purely speculative strand as it tries to imagine a world where we are able to feel our invisible EM infrastructure and their signals and processes as sensible pulses, rhythms and tickings. What kind of future society would unfold through the design of such altered sensory capabilities? Or conversely, what kind of society would develop the necessity for such sensory capabilities?.

The publication that accompanies the project can be purchased in paper but its digital version is entirely free.

Yuri Suzuki, Sound of the Earth: Chapter 3. Exhibition view. Photo: DSL Studio

In the foreground: Bosco Sodi, Perfect Bodies. In the background: Yuri Suzuki, Sound of the Earth: Chapter 3. Exhibition view. Photo: DSL Studio

Yuri Suzuki‘s soundoftheearth.org website invites users to listen to sounds from all over the world and to submit sounds that will join the global archive. Machine learning then links user-submitted sounds to their nearest sonic neighbours, creating a collective soundscape without borders.

The physical installation is a gigantic geodesic sphere situated at the entrance of Unknown Unknowns. Walking around the sphere, you can listen to a range of sounds that have been submitted via the soundoftheearth.org website.

More images of the exhibitions. Most of them are from Unknown Unknowns. An Introduction to Mysteries. Others from the other shows that are part of the Triennale:

Unknown Unknowns. An introduction to mysteries. Exhibition view. Photo: DSL Studio

Unknown Unknowns. An introduction to mysteries. Exhibition view. Photo: DSL Studio

Nonhuman Nonsense, Planetary Personhood; A universal declaration of martian rights, 2020-21

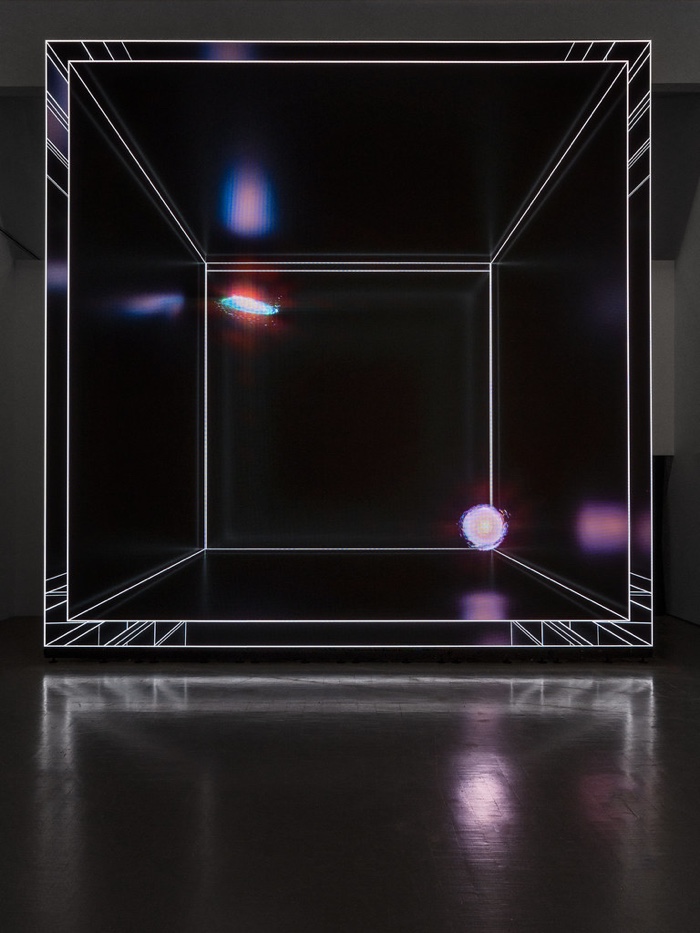

Björn Dahlem, The Still Expanding Universe, 2013. Photo: Achim Kukulies, Düsseldorf

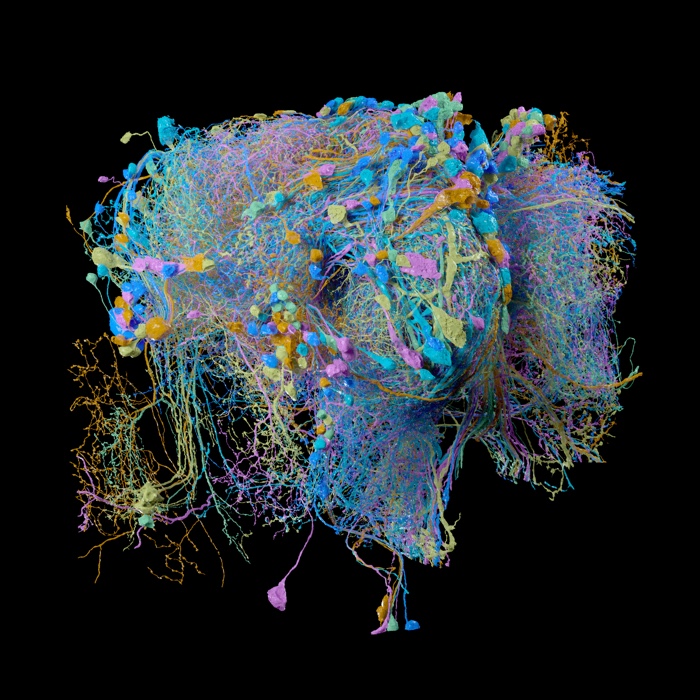

Philip Hubbard, Flyem/Hhmi-Janelia Research Campus, Google, Flyem Project, 2020

![]()

BIG + Icon Build + NASA, Project Olympus, 2020. Design for the first permanent settlement on the lunar surface; multi-material model

Vincent Fournier, Kjell Henriksen Observatory #1 [KHO], Adventdalen, Isola di Spitsbergen, Norvegia, 2010

Vincent Fournier, Mars Desert Research Station #11 [MDRS], Mars Society, San Rafael S 64 well, Utah, USA, 2008

In the foreground: Andrea Galvani. Instruments for Inquiring into the Wind and the Shaking Earth. In the background: Alighiero Boetti, Mettere al mondo il mondo, 1975. Exhibition view. Photo: DSL Studio

Refik Anadol, Universe Simulations: The Merging of Milky Way & Andromeda. Exhibition view. Photo: DSL Studio

Antonio Fiorentino, Dominium Melancholiae, 2014. Photo: Jean Brasille

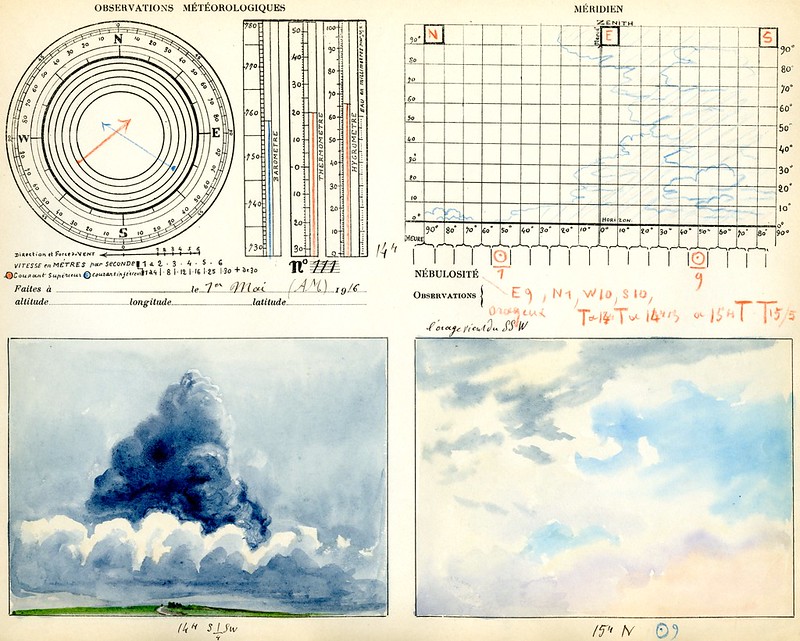

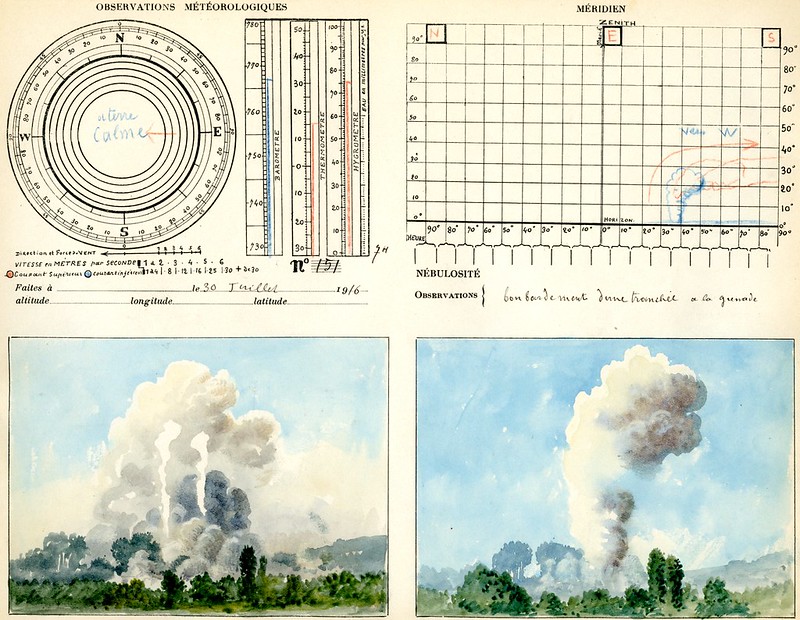

André des Gachons, Observations météorologiques, 1915-17

André des Gachons, Observations météorologiques, 1915-17

Three times a day (morning, early afternoon and at sunset), painter and illustrator André des Gachons would look at the sky and turn his weather observations into small watercolours. Between 1913 and 1951, he sent around 77,000 to the weather service in Paris.

Giovanni Agosti and Jacopo Stoppa, Il corridoio rosso. Exhibition view. Photo: DSL Studio

Giovanni Agosti and Jacopo Stoppa, Il corridoio rosso. Exhibition entrance. Photo: DSL Studio

Giovanni Agosti and Jacopo Stoppa, Il corridoio rosso. Exhibition view. Photo: DSL Studio

Unknown Unknowns. An Introduction to Mysteries, one of the main exhibitions of the 23rd International Exhibition at the Triennale, is curated by Ersilia Vaudo, the Chief Diversity Officer of the European Space Agency. The triennale is open until 11 December 2022.

Previously: An artificial planet made entirely of human bodies; Supre:organism. Alternative perspectives on space exploration, etc.

Also part of the Triennale di Milano: “Have we met?” A multispecies approach to the planet.