Like many people across the world, i started the year dispirited by the images of the fires in Australia. The country, it seemed, had become a testbed for the extreme climate conditions we’d all be facing soon. When I found myself in Frankfurt to visit Trees of Life – Stories for a Damaged Planet, i was bracing myself for similar reminders of how foolish and irresponsible our species is.

Strangely enough, that feeling of helplessness and discomfort didn’t materialise. Trees of Life might thus be one of the very few exhibitions that look at the Anthropocene without hammering the visitor with guilt. Instead of pointing us to all the things that are wrong with this world, the exhibition invites us to consider our real place in the world, in terms of space and time. It’s an invigorating, albeit profoundly humbling, experience.

Dominique Koch, Holobiont Society (film still), 2017

Trees of Life – Stories for a Damaged Planet. Video overview of the exhibition

Using artifacts from the Senckenberg Natural History Museum in Frankfurt as fragments of the world in the course of its evolution, the art exhibition presents bold new perspectives, new thought models that are anchored in science. Combined together, the artworks, the petrified trunk and amonites that had shared the Earth with early dinosaurs, the moldavites from a meteorite fallen on Germany 15 million years ago, Charles Darwin’s sketch of evolution and other pieces of scientific evidence challenge our anthropocentric worldview.

Trees of Life – Stories for a Damaged Planet inspires visitors to embrace new knowledge and critically reexamine established ways of thinking the world. Starting with a confrontation between “the survival of the fittest” and the more nuanced concept of the holobiont…

Symbiotic Earth: How Lynn Margulis rocked the boat and started a scientific revolution

A holobiont is an assemblage of a host and the many individual species living in or around it. Together they form an ecological unit. Reef-building corals and animal bodies are examples of holobionts. The concept of the holobiont was formulated by evolutionary theorist and biologist Dr. Lynn Margulis in her 1991 book Symbiosis as a Source of Evolutionary Innovation. Her theory that interdependence was a key driver of evolution first met with severe criticism, even derision. By stressing the importance of symbiotic or cooperative relationships between species, her theory challenged the mainstream competition-oriented views of evolution. Her ideas met with resistance outside of scientific circles as well. First of all, her theory of tiny and big species relying on each other didn’t sit well with the “survival of the fittest” doctrine that is still driving the capitalist rhetoric. But her theory also indicated a paradigm shift. Suddenly, humans were not at the apex of the world anymore, they were part of an intricate system in which each of their actions had repercussions.

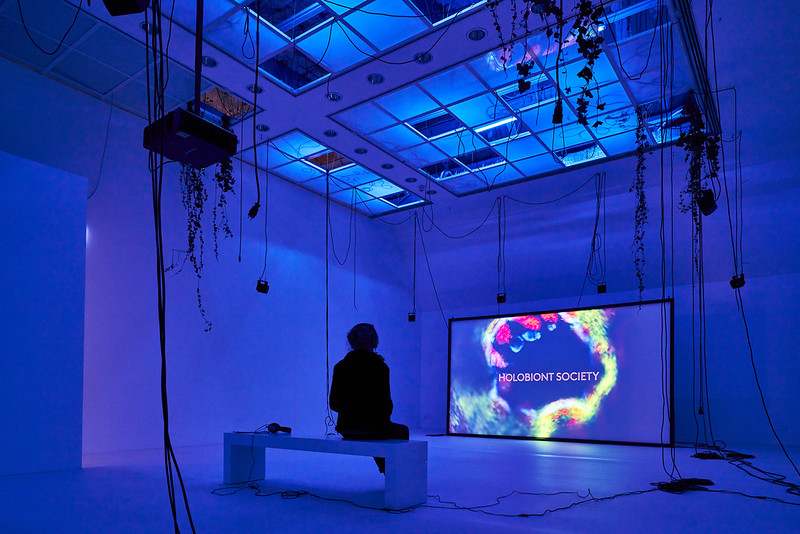

Dominique Koch, Holobiont Society, 2017. Installation view at Frankfurter Kunstverein 2019. Photo credit: Norbert Miguletz

Dominique Koch, Holobiont Society (film still), 2017

in her video Holobiont Society, Dominique Koch propels Margulis’ “heretical” theory of interdependency into the socio-political sphere. Her video installation interweaves images that evoke an ambiguous future with a soundtrack composed by Tobias Koch and interviews with theorists who have bittersweet, lucid and at times almost optimistic views on the world we are busy destroying.

American biologist and feminist Donna Haraway puts the holobiont concept in an ethical perspective. Since all species (no matter how small or modest-looking) are co-dependent on each other, we have to take care of each other. Ideas about actions to undertake for the future of the planet should be coming from below, not from positions of power.

Philosopher and sociologist Maurizio Lazzarato draws painful parallels between neoliberalism, with its ruthless appropriation of resources and accumulation of property, and the rise of the far right with its rhetoric of retrenchment that creates divisions between cultures, classes, sex, races, etc.

No matter how bleak their diagnostic, both Lazzarato and Haraway offer glimpses of hope: they see the rise of a new awareness, of new forms of resistance.

The images that accompany the interviews are ambiguous. They are visions of a powerful nature devoid of any human presence. They evoke a kind of Romantic sublime that doesn’t illustrate the interviews but gives the words of the thinkers a space to sink in and be further pondered upon by spectators. Electronic music by Tobias Koch fills in the room on a separate audio track. It’s only January but i doubt that this year i’ll come across any artwork that will move me as much as Holobiont Society did.

Sonja Bäumel, in collaboration with bacteriograph Erich Schöpf, realisation with molecular biologist Manuel Selg, Expanded Self II, 2015/2019. Installation view at Frankfurter Kunstverein 2019. Photo: Norbert Miguletz

Sonja Bäumel, in collaboration with bacteriograph Erich Schöpf, realisation with molecular biologist Manuel Selg, Expanded Self II, 2015/2019. Installation view at Frankfurter Kunstverein 2019. Photo: Norbert Miguletz

Sonja Bäumel, in collaboration with bacteriograph Erich Schöpf, realisation with molecular biologist Manuel Selg, Expanded Self II, 2015/2019. Installation view at Frankfurter Kunstverein 2019. Photo: Norbert Miguletz

Sonja Bäumel, in collaboration with bacteriograph Erich Schöpf, realisation with molecular biologist Manuel Selg, Expanded Self II, 2015/2019. Detail of the installation after 3 months spent at Frankfurter Kunstverein

Some scientific studies estimate that human cells make up only 43% of the body’s total cell count. The rest are microscopic creatures such as bacteria, viruses, fungi and archaea. They live in our gut, on our skin. Our health (including our mental health) depends on them as much as they depend on us. They help to digest our food, strengthen our immune systems, influence our mood, etc.

This fairly recent discovery that more than half of your body is not human seems to further challenge the so-called human exceptionalism and to strengthen Margulis’ interdependency theory. The very existence of the microbiota challenges our idea of humanity, prompting us to wonder whether we are individuals, multispecies entities or ecosystems.

In her work, artist Sonja Bäumel pays homage to our microbial companions, revealing their existence and enrolling their “collaboration” in the development of artworks. She has several pieces at Frankfurter Kunstverein. The one i found most spectacular is Expanded Self II, a living cast of her body that challenges our assumptions about the body as a hermetic entity.

Bäumel used agar to create a cast of herself. What she left behind on the nutritive substrate was her own microbiome. The agar was then sealed and the living organisms that had covered her body were left to grow, morph, bloom, expand and reveal the full extent of the artist’s skin flora.

The living artifact suggests that the human body is not one unit but a symbiotic ecosystem, an accumulation of the smallest parts: microorganisms that inhabit and rule the human hosts.

Edgar Honetschläger, Go Bugs Go (film still), 2018. Courtesy and Copyright the artist

Edgar Honetschläger, Go Bugs Go (teaser), 2018

Collection of prepared bugs in systematic arrangement, about 1880. Installation View at Frankfurter Kunstverein 2019. Photo: Norbert Miguletz. On loan: Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung

Collection of prepared bugs in systematic arrangement, about 1880. Installation View at Frankfurter Kunstverein 2019. Photo: Norbert Miguletz. On loan: Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung

Edgar Honetschläger, GoBugsGo, 2018. Installation view at Frankfurter Kunstverein 2019. Photo: Norbert Miguletz

Insects are other life forms whose survival we depend upon. In the past, men preserved bugs by pinning them and displaying them in museum collections. We still do that of course but in front of the collapse of insect populations, more proactive measures are needed. The disappearance of insects puts the future of the planet’s ecosystems at risk: no insects, no food for the reptiles, the amphibians and the fish. No pollination either so no food for us.

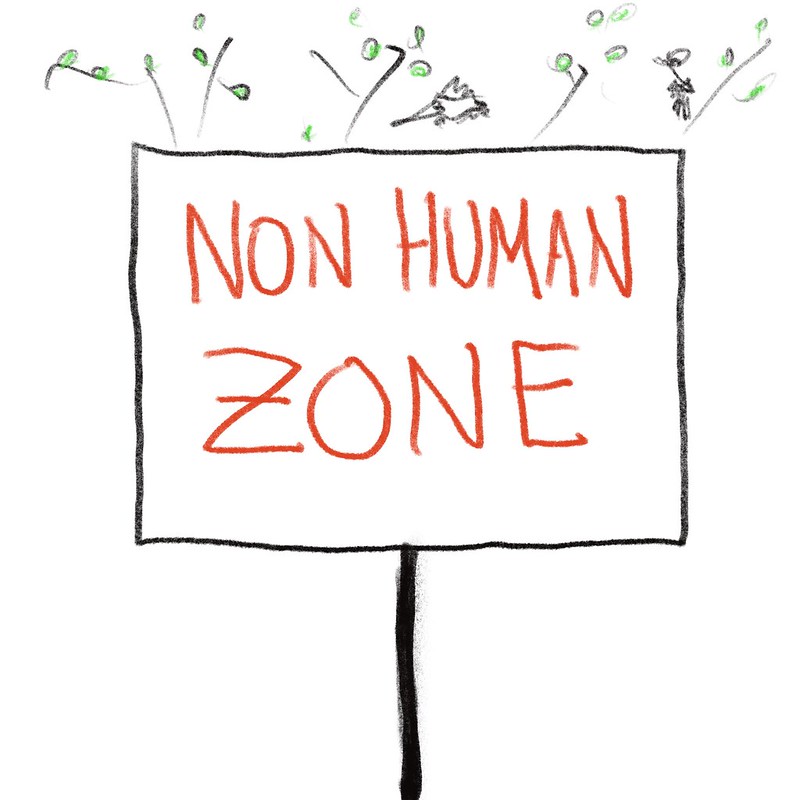

In 2018, artist and filmmaker Edgar Honetschläger teamed up with economist David Wöss, art historian Henny Ulm, to set up GoBugsGo, an NGO that endeavours to keep insects, birds and wild animals in this world.

The initiative invites citizens concerned about the future to join forces, buy land and give it back to nature, providing thus plants, insects, birds and other animals with a refuge from fertilisers and other human interference.

With its hand-drawn aesthetic and laid-back style, the film is engaging and humourous. The message however is strong: No insects = no food! A simple call of action addressed to our bellies. Perhaps the most moving aspect of this type of art-meets-life project is that it reminds us that nature needs insects more than it needs us. Were humans to disappear, biodiversity would recover. If the insects that die out, however, flora and fauna might never recover.

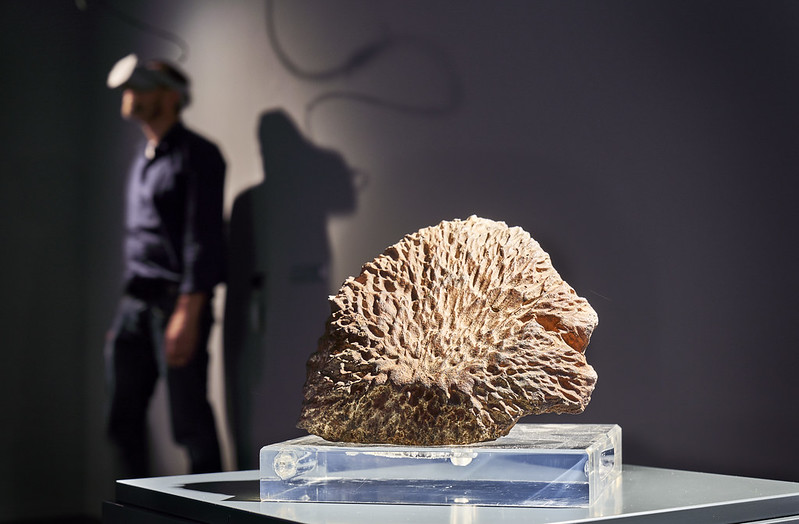

Agathoxylon, (Detail). Age: Lower Triassic, 225 million years. Photo: Norbert Miguletz. Installation view at Frankfurter Kunstverein 2019. On loan: Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung

Stromatoliths in limestone (Cyano bacterial colonies). Installation view at Frankfurter Kunstverein 2019. Photo: Norbert Miguletz

The exhibition also uses (deep) time and outer space to contextualise our existence on the planet and further question anthropocentrism.

The Senckenberg Natural History Museum lent examples of stromatolites from its collection. The stromatolites exhibited at Kunstverein were formed in the Precambrian period, the earliest part of Earth’s history that extends from about 4.6 billion years ago to about 541 million years ago, when hard-shelled creatures started appearing. The fossils consist of layers of primeval cyanobacteria, a single-celled photosynthesizing microbe which Margulis regarded as the basic unit of all life and also a source of free oxygen in the atmosphere.

Meteorites are even more mind-boggling. Formed 4.5 billion years ago at the birth of the solar system, these fragments of asteroidal and planetary bodies contain the chemical elements that make up our entire solar system and from which all life on our planet developed. For example, the water in our oceans might very well come from comets, the calcium in our bones and the iron in our blood from supernovae explosions, and the hydrogen (which makes up roughly 9.5% of our bodies) is a primordial element from the Big Bang. We carry chemical substances within us that are derived from the stars in the cosmos. The most distant corners of the universe are thus within and around us.

David M. Hillis, Derrick Zwickl and Robin Gutell, Plot, 2003. Installation view at Frankfurter Kunstverein 2019. Photo: Norbert Miguletz

All of the above suggests that the metaphor of the tree to represent the evolutionary process and the connections between species are no longer adequate.

Evolutionary biologist David Mark Hillis created the Hillis Plot, one of the first phylogenetic illustrations in which the position of humankind is visualised as a systemic part of the whole, and not in a superior position. The full-size graphic can be found online.

This project originated as an attempt at a new visualization in light of new laboratory methods and what was then becoming current knowledge. It was only with DNA sequencing of the genome that biologists were able to create a comprehensive taxonomic classification showing the relationships of organisms to each other.

It is a humbling representation of the place of mankind on this planet, miles away from Charles Bonnet’s Scala Naturae (1781) and other hierarchical visualisations that have placed mankind at the apex of all living beings and guided much of our Western way of seeing the world.

More works and images from the show:

Studio Drift, M16 + bullet, 2019. From the series Materialism. Photo: Ronald Smits

Studio Drift, AK47 + bullet, 2019. From the series Materialism. Installation view Frankfurter Kunstverein. Photographer: Norbert Miguletz

Ricarda Dennen, (Sound), Marius Jacob (CGI, Animation), Simone Rduch, Dario Robra, Martin Thul (Master Students, Intermedia Design Trier), Prof. Daniel Gilgen (Installation), Marcus Haberkorn (Sound Editing) (Hochschule Trier), Leben im Wassertropfen, 2019. Installation view at Frankfurter Kunstverein 2019. Photo: Norbert Miguletz

Meteorite Horace. Discovery year: 1940. Installation View at Frankfurter Kunstverein 2019. Photo: Norbert Miguletz. On loan: Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung

Cotylorhiza tuberculata (Spiegeleiqualle), wet preparation, occurence: Mediterranaen Sea. Photo: Sven Tränkner / Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung. On loan: Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung

Cotylorhiza tuberculata (Fried egg jellyfishes). Installation View at Frankfurter Kunstverein 2019. Photo: Norbert Miguletz. On loan: Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung

Sonja Bäumel, Installation view at Frankfurter Kunstverein 2019. Photo: Norbert Miguletz

Trees of Life – Stories for a Damaged Planet, curated by Franziska Nori with scientific advice from palaeontologist Philipe Havlik, remains open until 16 February 2020 at Frankfurter Kunstverein in Frankfurt.