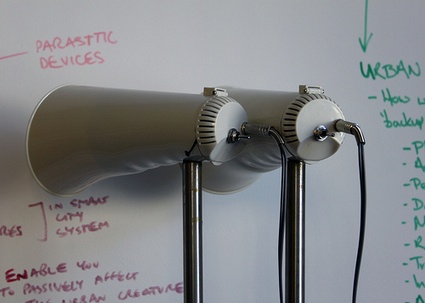

IBI trying Town Crier, a device which recognises and reads geo-tagged tweets through a megaphone

IBI trying Town Crier, a device which recognises and reads geo-tagged tweets through a megaphone

Last week, i was telling you about Le Cadavre Exquis, an interactive installation commissioned Making Future Work. This Nottingham-based initiative that called for artists, designers and organisations based in East Midlands to submit proposals that would respond to four distinct areas of practice: Co creation / Online Space, Pervasive Gaming / Urban Screens, Re-imaging Redundant Systems and Live Cinema / 3D.

The Urban Immune System Research, one of the 4 winning projects, investigates parallel futures in the emergence of the ‘smart-city’. During their research, the Institute has produced a series of speculative prototypes that combine digital technology and biometrics: one of the devices ‘functions as a social sixth sense’, a second one is a backpack mounted with 4 megaphones that shouts out geo-located tweets as you walk around, a third one attempts to make its wearer get a sense of what might it feel like to walk through a ‘data cloud’ or a ‘data meadow’.

The devices are the starting point of a series of user tests, performative research and public engagement events that seek to provoke debate and facilitate wider public discussion around potential urban futures, and our role in shaping them.

Just a few words of introduction about The Institute for Boundary Interactions before i proceed with our interview. IBI is a group of artists, designers, architects, technologists and creative producers conduct practice-based research into the complex relationships between people, places and recent developments in the field of science, technology and culture.

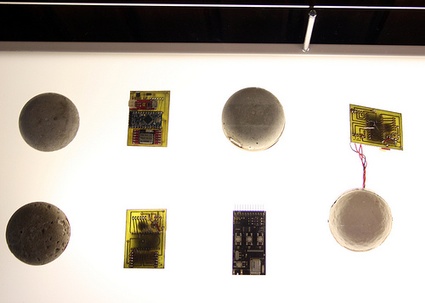

The Institute for Boundary Interactions display L.O.S.T. Stone and Sticky Data. Image credit: Melissa Gueneau, courtesy MFW

The Institute for Boundary Interactions display L.O.S.T. Stone and Sticky Data. Image credit: Melissa Gueneau, courtesy MFW

The name of your project is quite intriguing. Why did you call it Urban Immune System Research? How does the immune system of a city compare to the human body immune system, for example? What are the differences and similarities?

The Urban Immune System Research [UISR] project was the culmination of a two day event we ran in December 2010 as part of our LAB commission for Sideshow2010. We set out to discuss the relationship between notions of ‘intelligent’ systems, and principles of ecology. A whole raft of interesting and thought provoking ideas emerged but after some discussion they coalesced into the UISR project.

We found the immune system a fascinating and intriguing departure point because it demonstrates complex self-organising properties, but what’s interesting about this to us is how this kind of system is understood outside of scientific circles, in the everyday and within the context of the city. There is a general understanding of these kinds of systems, but we discovered an absence in the general lexicon of everyday terms with which to describe the kind of phenomena we explored in that workshop. So in part the name of the project is to ask questions about perceptions of intelligence and explore that gap between the science and the experience.

The interest in looking at urban space as an organism developed from thinking about this relationship between ecologies and intelligent systems. We looked at how these systems scale up, inspired by Geoffery West’s research into the similarities and differences between mammalian and urban scaling. So despite their very clear differences urban ecologies correlate strongly to biological systems and although made of different components behave in similar ways.

This research quickly grew into a fascination by what happens at that juncture where human technology meets ecology, how personal electronic devices, micro-biology and nano-technology effect us at the macro level. We were interested in how this will manifest macroscopically, or ecolologically if you will, and how this in turn will affect us individually as constituent parts of that urban ecology. Asking what form an Urban Immune System might take, and the devices we have developed under this title thus far are the first steps in our efforts to understand these ideas and their implications.

The devices all look to find alternative ways of connecting the individual directly to their ecology (the urban organism) and feel their place within it. These technologies operate to mediate our relationship to, and navigation through physical, social and virtual space. This process of upgrading could be seen as the momentum leading us towards transhumanism, an imagined yet possible future where the augmented body replaces natural selection as an evolutionary process in turn effecting the development of our ‘ecological’ surroundings.

This notion of transhumanism is another aspect that we we’re very interested to explore within this project as it has a lot of synergy with the notion of the urban organism. From one perspective we are looking at the inorganic environment as an organic organism, and from another we look at the organic organism as a component within an inorganic machine.

Trying IBI’s Sticky Data device. Image credit: Melissa Gueneau, courtesy MFW

Trying IBI’s Sticky Data device. Image credit: Melissa Gueneau, courtesy MFW

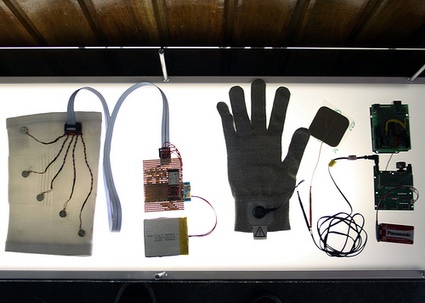

Sticky Data display. Image courtesy of IBI

Sticky Data display. Image courtesy of IBI

With The Sticky Data device you were asking “What might it feel like to walk through a ‘data cloud’ or a ‘data meadow’?” Did you find an answer to the question while you were testing the device? Is the experience of knowing how much data our body goes through every single second a stimulating one? or is it rather stressing? worrying? overwhelming? Does it influence the way you navigate a city afterwards? Would you for example avoid a quiet street because you’ve discovered that it might looks like a pleasant street empty of cars and passersby but with a data traffic that you find too intense?

The most stimulating thing about being able to sense geo-located data is the thought that you are physically feeling traces of people’s experiences in the same place where they happened. We think this gives an extra sense of connection to a place, even if only for a moment.

It’s difficult to say exactly what that should feel like, we’re still playing with different haptic sensations, but the device certainly challenged our assumptions about certain areas. For example, in one test we found a really high density of data outside a bus depot, whereas across the street near a stadium, a seemingly much more social and ‘eventful’ place, there was comparatively little. So you definitely get a sense that the topography of a city’s data layer can be quite different to that of its architectural space, but also an alternative sense of a places social makeup. So, finding themselves in a less sociable environment, did the inhabitants of the bus depot turn to more digital forms of social interaction, while the stadium offered enough ‘face to face’ social encounters that digital interaction was unnecessary?

The hope is definitely to ask people to question their relationship with space by providing a very different experience of navigating a city – the technologies that we use everyday are creating this digital topography, so how does this affect the urban organism and our interactions within it?

Sticky Data App Field Test

At the end of your description of the Sticky Data project, you explain that “As the user moves on, data seeds will be copied and dropped in new locations spreading them throughout the city or collected and cataloged by the device.” Why did you feel the need to add this ‘manipulation’ of the data? Is it not going to make the ‘datascape’ too confusing?

This was an idea that came from discussions around the notion of the Urban Immune System. We talked about the idea that perhaps urban space already has an immune system of sorts that operates to keep the city within normative parameters. We discussed this redistribution as something that might function like an immunisation to bolster this existing immune system by disrupting it with non-normative behaviour to see how it responded.

We were interested in devices that have parasitic (viral) properties or where the owner could engage in the production of data and urban data configuration using the traces that others leave behind just through wearing the device and walking. We leave behind traces of our electronic identities almost daily and it’s something that we are not really aware of.

Also, if data is part of our physical world then it in some way degrades or gets pasted over like the posters in a metro station over time, the datascape is constantly shifting. We were going to be selective over how what qualities of data we were looking for, so older data might not be as ‘memetically healthy’ and so may not spread as far or at all. We were interested in being deliberately disruptive to see what might happen if we push messages into and across territories. So the Sticky Data project could sift through what is there in electronic space to find data that might benefit the wearer or be most disruptive.

Testing sticky data. Image courtesy of IBI

Testing sticky data. Image courtesy of IBI

Conductive glove. Image courtesy of IBI

Conductive glove. Image courtesy of IBI

One of the objectives of UISR is to explore new ways to ‘sense the social characteristics of a city as you would temperature, or air quality.’ Do you have a better idea of Nottingham (or any other city where you have experimented with the devices) after having tested your prototypes through its streets? Do you see the city with another eye?

The devices have opened up new ways of experiencing the city, so we’re pleased about that. When testing the Sticky Data device we discovered huge amounts of twitter data in surprising places – like the bus depot on an unremarkable street that we mentioned before. So the device certainly challenges your perceptions of the social makeup of your environment and certain expectations or pre-judgments you may have made. Of course it also has the ability to re-enforce some prejudices too. However, not knowing what the messages are it leaves you to read into their presence from what is physically around you, building the virtual narrative into the physical narrative of your surroundings.

In the tests we have carried out we have felt some interesting things that have challenged and re-enforced our assumptions of particular locations. However no one of us has tested the device thoroughly across the city yet as we are still fine tuning it and have remained largely within familiar areas. Personally I am looking forward to taking the device somewhere totally unfamiliar and finding out what a city you’ve never visited before feels like. If you have no pre-suppositions about a particular street does the device make it easier to walk down or give you spidey-sense tingle that there will be something unpleasant around the corner? We just don’t know yet.

LOST display. Image courtesy IBI

LOST display. Image courtesy IBI

Could you describe The LOST (Local Only Shared Telemetry) device? How does it work?

The idea with the LOST device is for it to function as a social sixth sense. It’s a wireless device, kept in close contact with the body that stores its owners profile. It simply transmits and receives this profile data over relatively small distances. When it finds a similar signal to its own the device communicates this to the owner by changing its temperature.

We wondered how a system that is similar to that of ants leaving pheromone trails might work in the social context of a city. In antithesis to the omniscient Internet this device doesn’t use any kind of infrastructure as it communicates only locally, so the user has to physically travel to find new data rather than just clicking hyperlinks. The sensory feedback the wearer receives is specific only to the time and place in which they find themselves.

It’s a thought experiment thinking that if everyone in an urban space wore such a device you would develop a very granular sense of the social make up of your very local vicinity with the cumulative heating, cooling effect of everyone else’s device surrounding you. In such a way you could get a very clear feeling about whether a particular area is sympathetic to you as an individual or not. Kind of like blind man’s buff, but instead of other players saying warmer or colder you simply feel it directly.

As with the sticky data device, having no lingual or visual output, it interfaces at a somatic level – we’re interested in what happens when social data is perceived physiologically rather than visually. By integrating these digital sensory devices into our normal bodily senses we can start to understand the possible positive and negative implications not just of existing systems but also our rapid progress towards transhumanism.

The notion of being a trans-human is very exciting but until technologies are developed we can never really know what the implications of them will be. Devices like the LOST device allow ways of imagining how technological and biological integration might operate and in turn perhaps begin to understand their consequences individually and socially.

IBI trying Town Crier, their latest device which recognises and reads geo-tagged tweets through a megaphone. Image credit: Melissa Gueneau, courtesy MFW

IBI trying Town Crier, their latest device which recognises and reads geo-tagged tweets through a megaphone. Image credit: Melissa Gueneau, courtesy MFW

IBI trying Town Crier, their latest device which recognises and reads geo-tagged tweets through a megaphone. Image credit: Melissa Gueneau, courtesy MFW

IBI trying Town Crier, their latest device which recognises and reads geo-tagged tweets through a megaphone. Image credit: Melissa Gueneau, courtesy MFW

I’m afraid i forgot the name of the device you used for the public performance on the day of Making Future Collaboration Work. Beyond the fun and spectacular side of the performance, what are you trying to achieve with this piece?

That was the Town Crier. It’s a backpack mounted with 4 megaphones that shouts out geo-located tweets as you walk around. The other two devices we made offer very subtle, private interactions, so we wanted to try something a little more confrontational.

The idea was to use the disparity between what can often be intended as very private or relatively anonymous reflections, and the openness of physical spaces that they are associated with. Shouting out these bits of text wrenches them, quite forcibly, back into public view. On the other hand though, the electronic voice puts all these statements on an even plane, and democratizes them giving a sense of the voice belonging to the place rather than any individual. These statements are at different times nonsensical, funny, or timely and touching, but they all add to the texture of a place, offering a glimpse of the collective memory embedded within it.

Town Crier Public Field Test Documentation

Town Crier. Image courtesy IBI

Town Crier. Image courtesy IBI

Are you still working on the project? Do you plan to push the prototypes any further? Add new ones?

We see this as a long term research project so we are definitely still working on not only testing and improving current devices, but also using this process to develop our understanding of the data city, the technologically augmented human, and the ecology that they create.

We’re currently developing the town crier into some kind of performance work and playing with the Google Navigation voice more as a means of exploring the way in which the network operates as a continuous landmark in our landscape.

The Sticky Data and LOST device projects are still very much a works in progress. With Sticky Data we are going to continue experimenting with the way that the data is sensed or output. The immediate question we want to address is the character of the sensation in relation to the density of data being sensed. Similarly, what types of data are being sensed, and what are the most appropriate modes of sensation for these different bits of data? With the LOST stone, we are going to play with what information is used to form the user profile to find which provide most effective functionality.

Once we’ve worked out the technical challenges with both of these devices we want to produce enough of them for each of us to wear and live with them for a significant period of time. Perhaps with the LOST device also using willing volunteers to test them to increase the area density.

We’d like to know what it would feel like if I put on a sticky data sleeve at the same time you put on your watch in the morning and wore it wherever you go for a month. Is it an irritation, will you get muscle spasms, or forget you’ve got it on most of the time and only notice more drastic or uncharacteristic changes?

After this we hope to have a better idea of how we can develop the project further, fine tuning these devices and perhaps developing new ones. To put it in techno-garb, perhaps create the Urban Immune System 1.0 rather than its current beta version.

It is perhaps worth making clear that the focus will remain on provoking speculation on what the possible social implications of developing this sort of technology might be, rather than trying to create a cure for urban illness. Technology is exciting and interesting, however the implications of innovations are rarely visible until you have the grace of hindsight. One can only speculate how developments might or might not change the world, but that process of speculation is really interesting and tells us something about our current understanding of our society and technological culture.

Thanks Institute for Boundary Interactions!

Previously: Le Cadavre Exquis.