The Sick Rose” Disease and the Art of Medical Illustration, by academic medical historian Dr Richard Barnett.

Available on Amazon UK and USA.

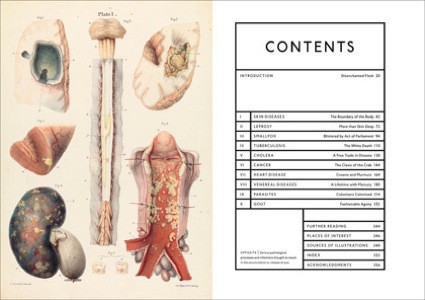

Publisher Thames and Hudson writes: The Sick Rose is a visual tour through the golden age of medical illustration. The nineteenth century experienced an explosion of epidemics such as cholera and diphtheria, driven by industrialization, urbanization and poor hygiene. In this pre-color-photography era, accurate images were relied upon to teach students and aid diagnosis. The best examples, featured here, are remarkable pieces of art that attempted to elucidate the mysteries of the body, and the successive onset of each affliction. Bizarre and captivating images, including close-up details and revealing cross-sections, make all too clear the fascinations of both doctors and artists of the time. Barnett illuminates the fears and obsessions of a society gripped by disease, yet slowly coming to understand and combat it. The age also saw the acceptance of vaccination and the germ theory, and notable diagrams that transformed public health, such as John Snow’s cholera map and Florence Nightingale’s pioneering histograms, are included and explained. Organized by disease, The Sick Rose ranges from little-known ailments now all but forgotten to the epidemics that shaped the modern age.

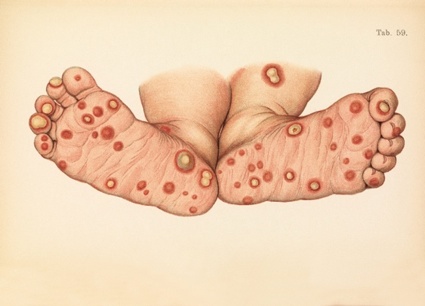

The feet of an infant with hereditary syphilis, showing the skin covered in pustules. Photograph: Wellcome Library, London

The feet of an infant with hereditary syphilis, showing the skin covered in pustules. Photograph: Wellcome Library, London

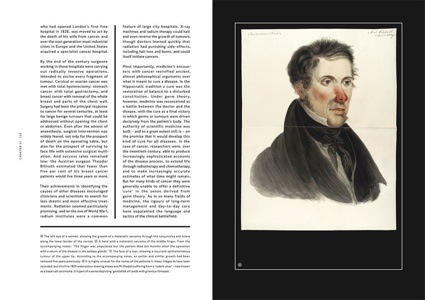

The images in the book might not be to everyone’s taste. They date back from the late 18th century to the early 20th century, a time when medicine was moving away from the principles of Hippocratic humoralism that saw the body as unified whole and starting to see disease as a form of specific physical disorder. It’s no coincidence that in the early 19th century, Mary Shelley would imagine Victor Frankenstein, a scientist who subverted the integrity of the body and created his living creature by assembling parts originating from various human corpses.

The period also saw the beginning of the mass-production of books for the education of medicine students. The medical images these books contained were the result of a collaboration between several professions. Physicians, surgeons and anatomists would first secure, dissect and prepare bodies. Draughtsmen would then be called to reproduce the subject in great details and under the guidance of the medicine man. Finally, engravers would cut woodblocks or copper plates as mirror images of the illustration. The anatomical reality would thus have to be filtered by the minds, eyes and hands of subjective humans. That’s without taking into account any further involvement of the printers and publishers.

A 13-year-old boy with severe untreated leprosy. Photograph: Wellcome Library, London

A 13-year-old boy with severe untreated leprosy. Photograph: Wellcome Library, London

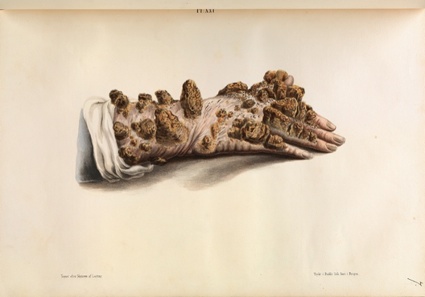

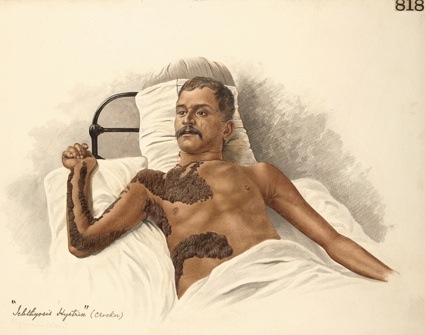

Severe tubercular leprosy (or ichthyosis) of the hand. Photograph: Wellcome Library, London

Severe tubercular leprosy (or ichthyosis) of the hand. Photograph: Wellcome Library, London

The Sick Rose is a wonderful book. Not just because of the eye-catching illustrations but because Richard Barnett is a talented narrator. And the stories he tells are fascinating.

First of all, there is the origin of the corpses to dissect and portray. At first, they came from the gallows. Starting in 1752, the sentence for murder in English courts included indeed public dissection. Body snatchers would supply corpses of pregnant women and foetus and any extra cadaver if needed. The 1832 Anatomy Act, however, abolished the dissection of executed criminals but allowed anatomy schools to use the body of anyone who had died unclaimed in hospitals. Which means that it was no longer crime that lead you to the dissection table, it was poverty.

Then there are the stories that accompany each disease studied in the book. Leprosy, aka the “Imperial Danger”, that reappeared in the 19th century when doctors and missionaries traveled to tropical colonies. Smallpox and how the first vaccine was successfully developed with the help of pretty milkmaids. Venereal diseases and syphilis in particular which was treated by injection or ingestion of mercury. Et cetera.

My favourite page in the book may well be page 246, aka “Places of Interest”, a list of the pathology museums, anatomy museums, medical history centers and other public collections of all things bodily and gruesome. I’m definitely going to drop by some of those in the coming weeks.

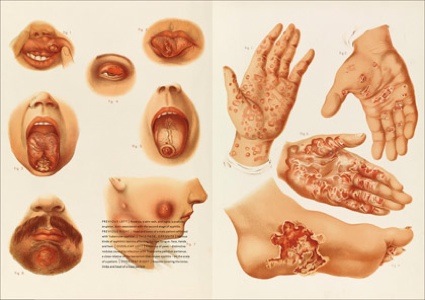

Left: The face of a male patient showing rupia, a severe encrusted rash associated with secondary syphillis. Right: A woman’s face, affected with lesions of impetigo. Prince A. Morrow, Atlas of Skin and Venereal Diseases including a brief treatise on the pathology and treatment, London, 1898

Left: The face of a male patient showing rupia, a severe encrusted rash associated with secondary syphillis. Right: A woman’s face, affected with lesions of impetigo. Prince A. Morrow, Atlas of Skin and Venereal Diseases including a brief treatise on the pathology and treatment, London, 1898

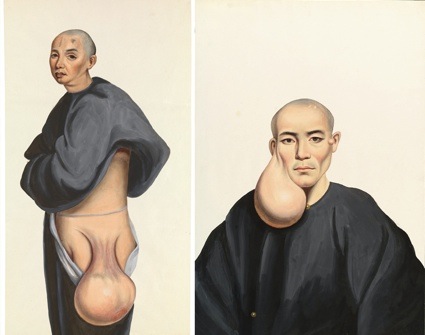

Left: A man with a large pendant hip tumour. Right: A man with a large pendant face tumour. Lam Qua

Left: A man with a large pendant hip tumour. Right: A man with a large pendant face tumour. Lam Qua

A child with blisters and other lesions affecting the skin. Photograph: Wellcome Library, London

A child with blisters and other lesions affecting the skin. Photograph: Wellcome Library, London

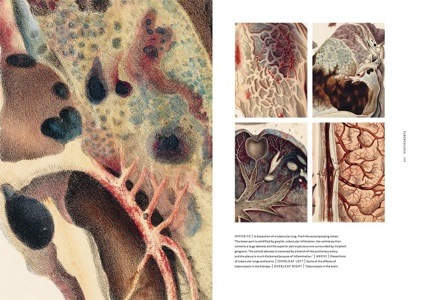

Diffused and spotted pulmonary apoplexy in a tubercular lung, drawn by Berhari Lal Das at the Medical College of Calcutta in 1906. Photograph: St Bartholomew’s Hospital Archive

Diffused and spotted pulmonary apoplexy in a tubercular lung, drawn by Berhari Lal Das at the Medical College of Calcutta in 1906. Photograph: St Bartholomew’s Hospital Archive

Views inside the book:

The Guardian has a photo gallery.

Dr Richard Barnett will have a conversation with journalist and historian Frances Stonor Saunders about ‘The Sick Rose’ on June 19 at the Wellcome Collection.

Related story: Doctors, Dissection and Resurrection Men.