Olaf Brzeski, Dream – Spontaneous Combustion, 2008 (image by Dirk Houbrechts)

Olaf Brzeski, Dream – Spontaneous Combustion, 2008 (image by Dirk Houbrechts)

Katarzyna Kozyra, Punishment and Crime, 2002

Katarzyna Kozyra, Punishment and Crime, 2002

At first sight, an exhibition entirely dedicated to art from Poland might seem like an exotic eccentricity but visits to art fairs, exhibitions and festivals have opened my eyes times and times again to the high number of talented artists from Poland. Or maybe it’s just that i’m especially sensitive to what they do: the heavy, meticulous, and at times distressing, historical references in Robert Kusmirowski’s mock-ups, Krzysztof Wodiczko‘s homeless vehicles, Artur Żmijewski’s video documentation of social experiments, etc.

I was therefore really looking forward to see The Power of Fantasy – Modern and Contemporary Art from Poland at the BOZAR Centre for Fine Arts when i went to Brussels last week.

Divided throughout the 19th century, occupied during the Second World War, and subsequently under the Soviet yoke for decades, Poland became a democracy in 1989. In this wounded country, victim of a succession of oppressive regimes, there developed a flourishing culture that gave expression, down the centuries, to a spirit of resistance to any order imposed from outside. Via the absurd and the fantastic, Polish artists reacted to the chaos of the real world with art imbued with a spirit of resistance, not in order to flee reality, but with a view to reconstructing it.

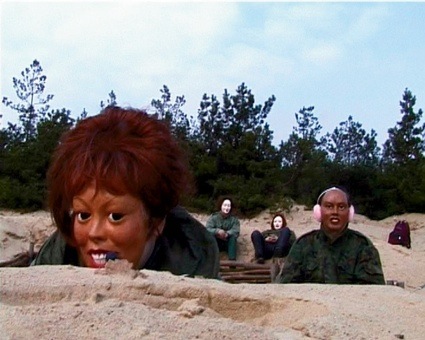

Memories of communism, shadows of the occupation, fantasy, irony and look at the catchy image used to promote the exhibition:

Clearly, that was a show i was going to like. Unfortunately, BOZAR might be a bit of a kill-joy because of 1. the fairly high entrance price, it’s 15 euros to see 3 exhibitions (you can also buy tickets to see individual exhibitions, their price is 6 euros, 6 euros and 3 euros which makes the ‘combined ticket’ such a fantastic bargain.) 2. the absolute interdiction to take picture. Which would be fine if BOZAR provided visitors with good photos of the shows on their website. Instead, you have a to make-do with a couple of unsatisfactory photos that were taken in other contexts. Or buy the catalogue.

But let’s get back to the exhibition:

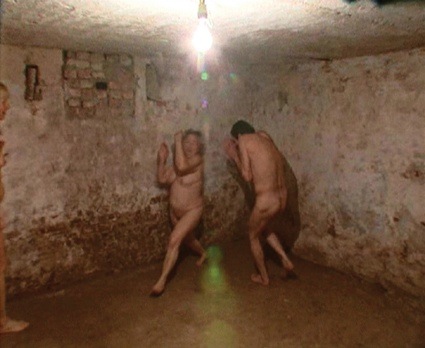

Artur Żmijewski, The Game of Tag, 1999

Artur Żmijewski, The Game of Tag, 1999

Robert Kusmirowski, D.O.M., 2004 (image by Dirk Houbrechts)

Robert Kusmirowski, D.O.M., 2004 (image by Dirk Houbrechts)

Kuśmirowski and Żmijewski whose work i mentioned earlier were came with heavy boots. The former reconstructed a catholic cemetery using cardboard, wood, heaps of dirt and polystyrene while the latter showed the short film The Game of Tag, in which adults of various ages enter a former concentration camp gas chamber. They are naked and asked to play tag. After the initial moments of awkwardness, the players seem to go for it and merrily run around the death chamber. The artist compares the experiment to a therapy used in psychology: the re-enactment of a traumatic event with a simultaneous shifting of its meaning.

Zbigniew Libera, The exodus of the People from the Cities, 2010 (image Houbi)

Zbigniew Libera, The exodus of the People from the Cities, 2010 (image Houbi)

A couple of meters away from the video, Zbigniew Libera, who made the headlines with his Lego Concentration Camp (1996), is showing a large, staged photo titled The Exodus of the People from the Cities, which probably meets all the clichés we might come up with when we stop and think about people who immigrated from Poland to work in “Western” countries.

Katarzyna Kozyra, Punishment and Crime, 2002

Katarzyna Kozyra, Punishment and Crime, 2002

Katarzyna Kozyra, Punishment and Crime, 2002

Katarzyna Kozyra, Punishment and Crime, 2002

Perhaps the most fascinating work for me, Katarzyna Kozyra’s Punishment and Crime introduces us to a group of men wearing masks of pin-ups as they engage in their favourite hobby: explosions, shooting and other paramilitary activities. The weaponry they use is impressive: homemade explosives, MG42s, flame throwers, rocket propelled grenades, bazookas, etc. The wooden shacks and cars that they torch, explode and pierce with projectile were built or brought for the express purpose of being destroyed. Crime follows crime (their weekend pastime is illegal) but punishment never ensues.

Art historian Paulina Pobocha writes that we must imagine that these war enthusiasts have already been punished. Like in so many of Kozyra’s works, the subject of Punishment and Crime is only partially that which we see projected on the screen. Outside of our field of vision, but integral to the piece is the context that gave birth to this strange (or not so strange) behavior: the society that cultivates this insatiable need for violence. The crime, which follows, is a possible, and perhaps inevitable, outcome, one which these men are consumed by and destined to enact over and over again.

Many of the works in the exhibitions echo 40 years of communist’s ideals, aesthetics and control.

Julita Wójcik, (image by Dirk Houbrechts)

Julita Wójcik, (image by Dirk Houbrechts)

Julita Wójcik’s knitted replica of a string of communist-era apartment buildings in beige and pink yarn stretches from one end of the room to the other.

Piotr Uklanski, Untitled (Solidarnosc), 2008

Piotr Uklanski, Untitled (Solidarnosc), 2008

Piotr Uklanski‘s large scale aerial photographs were created with the help of 30,000 men. Dressed in red and white, they were choreographed to spell the word “Solidarnosc”, the first non-communist party-controlled trade union in a Warsaw Pact country. The photo was shot in Gdansk, by the shipyard that became one of the icons of the end of communism.

The work directly nods to the photo-staging of the Soviet propaganda machine. The second image, however, shows the crowd disbanding and going opposite ways.

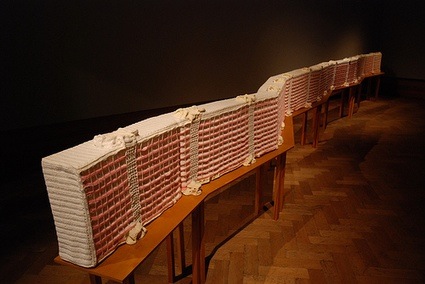

Katarzyna Józefowicz, Habitat, 1993-96 (image by Dirk Houbrechts)

Katarzyna Józefowicz, Habitat, 1993-96 (image by Dirk Houbrechts)

Katarzyna Józefowicz, Habitat, 1993-96 (detail)

Katarzyna Józefowicz, Habitat, 1993-96 (detail)

Katarzyna Józefowicz built a stunning construction filled with models of the typical furniture sets found in every Polish home when she was a child. Habitat highlights in a seducing way the standardization of Polish interiors that used to look almost exactly identical wherever you lived in the country.

Maciek Kurak‘s Fifty-Fifty is an old-model FIAT car turned upside down and powering a sewing machine (unless it’s the opposite?)

Maciek Kurak, Fifty-Fifty

Maciek Kurak, Fifty-Fifty

Janek Simon, Chleb krakowski, 2006

Janek Simon, Chleb krakowski, 2006

Janek Simon‘s Chleb krakowski (“Krakow bread) is a loaf mounted on robotic bug legs.

Maciek Kurak, Fifty-Fifty

Maciek Kurak, Fifty-Fifty

Maciek Kurak, Fifty-Fifty (detail)

Maciek Kurak, Fifty-Fifty (detail)

The Power of Fantasy – Modern and Contemporary Art from Poland was curated by David Crowley, Zofia Machnicka and Andrzej Szczerski, it remains open until Sunday 18.09.2011 at BOZAR Centre for Fine Arts in Brussels.

Tadeusz Kantor, Trumpet of the Last Judgment, 1979 (photo by Dirk Houbrechts)

Tadeusz Kantor, Trumpet of the Last Judgment, 1979 (photo by Dirk Houbrechts)

Previous posts featuring the work of Polish artists: DIY tractor culture in Poland, Machines from a past that never was, Artur Żmijewski: The Social Studio, M10, Venice Biennale of Architecture: the Polish pavilion, Wagon, Book review: Urban Interventions – Personal Projects in Public Spaces.