In 1930, economist John Maynard Keynes predicted that technological progress would free us from long hours of labour. We would be working 15-hour weeks and, our material needs satisfied, we’d spend the rest of our life as we please. We do indeed work fewer hours compared to 100 years ago. Yet, it feels like we are more exhausted than ever. Even Covid-19 has given a new flavour to the conundrum. Most of us entered lockdowns thinking we’d catch up on books, films d’auteur and brush up on our Dutch but we soon found that we were as anchored to our desks as ever. Perhaps even more. In fact, it seems that being gifted with unlimited time has made us lose touch with the meaning and measure of time.

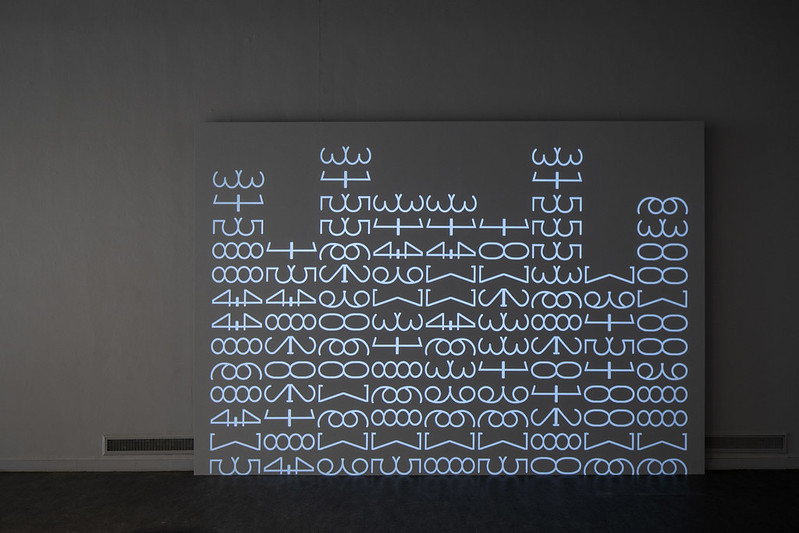

Andy Weir, Pazugoo, 2020

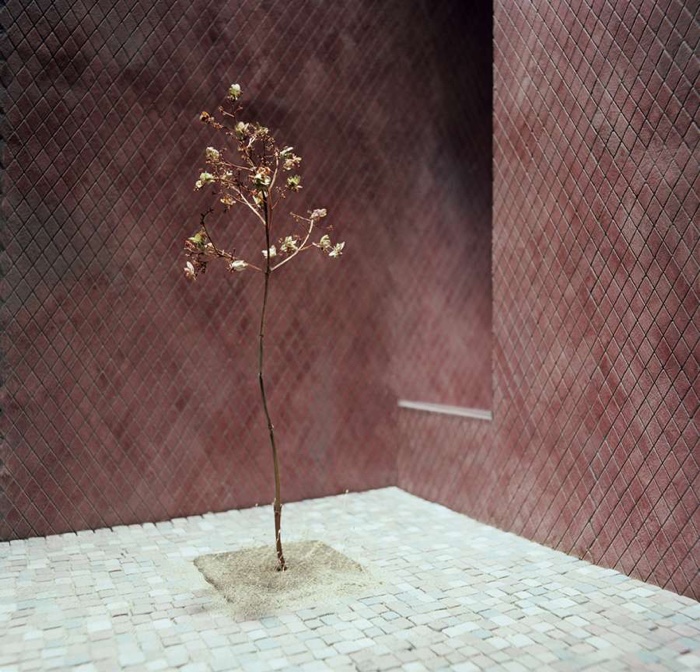

Helga Schmid, Circadian Dreams, 2020. Photo: Kristof Vrancken

The Work of Time, an exhibition curated by Ils Huygens for Z33 House for Contemporary Art, Design & Architecture, dissects the relationships between time, knowledge and learning. The artists selected for the show invite us to shift our attention to other dimensions of time such as inner time, biological time, dream time or the deep geological time of the earth. Their works ponder upon questions such as:

In a world that values speed, efficiency and productivity, is there any room left for slow human processes such as doubt, dialogue, democracy or even imagination? And what happens when important issues such as climate breakdown and radioactive waste force us to think on a radically different scale?

The exhibition is articulated around 3 sections. The one I found most thought-provoking, A Time to Expand: Learning from Deep Time, stems from exchanges between artists and Belgian nuclear scientists about the possibility to visualise the inconceivably long lifespan of radioactive waste. The artists explore the (in)feasibility of building eternal infrastructures that will not only stand the passing of time physically but that will also be able to pass on their message of toxicity and danger from generation to generations over thousands of years. The works in this chapter articulate the limits of human knowledge and technology and the need to include cultural, ethical and philosophical points of view into our elaboration of the future.

Maarten Vanden Eynde, Half Life, 2019. Installation view: The Work of Time, Z33. Photo: Kristof Vrancken

Half-life, in radioactivity, is the interval of time required for one-half of the atomic nuclei of a radioactive sample to decay. Half Life is also a series of copies in baked Boom clay of the storage containers used for nuclear waste in Belgium. The Boom clay comes from a strata of clay, between 200 and 400 metres deep that is being tested as one of the possible geological locations for Belgium to store its radioactive waste.

That same clay is used to make an exact copy scale 1: 1 of the storage container. The next model in the series is exactly half the size. The third is half of the second container. And so on. After nine steps or nine lives, the original size of 1335mm has shrunk to 5.21mm, after which it becomes practically invisible to the human eye.

The decrease in size is a direct echo of the decrease of nuclear radiation. The work visualises both the process that takes place underground and the material that protects it. In a distant future, where languages that we now think of as solid and strong might have disappeared or be understood only by a tiny minority of the human population (think of Latin which used to be widely spoken or at least read in most of Europe), a similar visualization could play a vital role in transmitting information about the perilous material hidden below the ground.

Alexis Destoop, Hourglass, 2019. Installation view: The Work of Time, Z33. Photo: Kristof Vrancken

Alexis Destoop’s digital composition consists of a series of photographs taken inside HADES, the Belgian underground research laboratory for experimental research on geological disposal for high-level and/or long-lived radioactive waste. The photographs reveal how organic and geological elements are quietly invading man-made infrastructures. Water is seeping through cracks, clay is forcing its way in, concrete is rusting. The images emphasise the impossibility of designing buildings that can last for eternity.

Thomson & Craighead, Temporary Index, 2016 — 2017. Installation view: The Work of Time, Z33. Photo: Kristof Vrancken

Vertical clocks projected on the wall count down the seconds necessary for a nuclear waste site to be safe again. Each countdown clock refers to a different location. Some are underground repositories of radioactive waste. Others correspond to places hit by nuclear disasters. The latest addition is the clock for the Category A site in Dessel, a municipality near Antwerp which has been selected to host the first shallow land disposal facility for low-level radioactive waste in Belgium.

The data collected by scientists working at each site was used to accurately calculate the half-life of the radioactive materials at the site. The data, which correspond to timescales so overwhelming they become abstract, is made more tangible. Its meaning, so disquieting, is given a hypnotising, almost soothing shape.

Andy Weir, Pazugoo, 2020. Installation view: The Work of Time, Z33. Photo: Kristof Vrancken

Andy Weir, Pazugoo, 2020. Installation view: The Work of Time, Z33. Photo: Kristof Vrancken

Andy Weir investigated how we can inform the hundreds and thousands of generations to come that they might find themselves in the vicinity of a repository for nuclear waste. The answer might not reside in monuments and words that become more inscrutable with each passing century. Many myths and legends, however, have stood the test of time. Weir suggests entrusting a new archaeological figure with the mission to carry out a message to intelligent creatures that will/might inhabit the planet in the distant future.

The cautionary figure he proposes is a distant disciple of Pazuzu, the Mesopotamian demon of epidemic, wind and dust. Pazuzu both issued warnings and offered protection. Pazuzu amulets were often buried near entryways or worn as a protective spirit against destruction.

Weir reinvents the powerful demon-gods of the underworld and calls him Pazugoo. Pazugoo figurines, like the myths that accompany them, can be passed down for generations. Used to mark potential repository sites, they are intended as archaeological artefacts that will be studied by generations to come.

The Pazugoo exhibited now at Z33 is a new prototype informed by his research on the nuclear sites in the Mol and Dessel area in Belgium. The winged Pazugoo echoes local elements from the landscape and legends.

Another chapter of the exhibition, A Time to Unwind: Unlearning Clock Time, invites visitors to challenge conventional understandings of time. Instead of focusing on acceleration and productivity, the works highlight other time dimensions, such as non-Western time, biological time, sleep time or dream time.

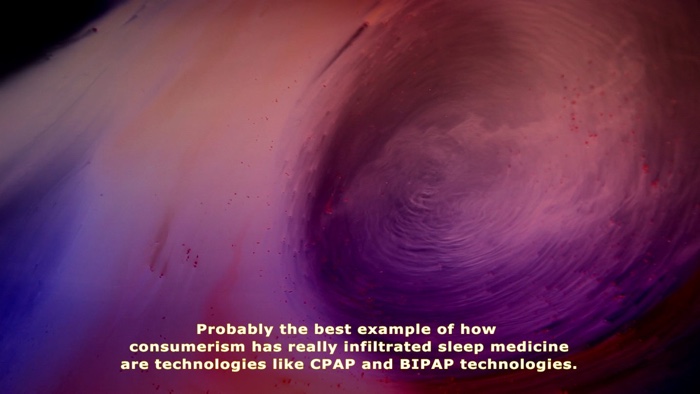

Danilo Correale, No More Sleep No More, 2014 — 2016

Danilo Correale, No More Sleep No More, 2014 — 2016

In 2014, Danilo Correale started a series of conversations with various experts on sleep and in particular on the dictates of neoliberal capitalism over our sleep patterns. His research led him to interview doctor David M. Rapoport, anthropologist Matthew J. Wolf-Meyer, historian Roger Ekirch, sociologist Simon Williams, labour studies scholar Alan Derickson, geographer Murray Melbin, philosopher Alexei Penzin and feminist scholar Reena Patel.

Correale’s 4-hour long video features extracts of these conversations. They reveal the tensions between the unyielding urge to be productive and the impact that sleeplessness has on productivity but also on social life as well as physical and mental health.

Historian Roger Ekirch, for example, argues that industrial capitalism’s relentless need for productivity has shaped our sleeping habits. Not only did we sleep more in the past but we also used to divide our sleep into two shifts. Until the Industrial Revolution which imposed stricter, less intuitive sleep/wake schedules on the workers.

No More Sleep No More suggests a very near future when productivity will not only encroach on every waking hour of the day, as it already does, but will also take control over our sleeping cycles.

The film features a dreamy, sci-fi screening of hypnotizing moving fluids inspired a period of sleep deprivation the artist experienced himself.

I first saw this visual essay on the chronopolitics of sleep and wakefulness at Kunsthalle Wien in 2017. It remains one of my favourite works to date.

Teis De Greve, A Ditto, Online Device, 2020. Photo: Kristof Vrancken

Teis De Greve, A Ditto, Online Device, 2020. Photo: Kristof Vrancken

A Ditto, Online Device brings side by side the constantly changing stream of online data and the much quieter flow of print. Two desktop printers were hacked so that they can decipher words. The printers are set to work only with pages that already feature texts. Visitors are invited to feed paper into the printer. Or rather in these COVID-19 times, are invited to ask a member of staff to show them how it works. The installation scans the pages and searches for related content on social media and online news feeds. The printers then spit our a glossary of topics and concepts related to the current time crisis, adding thus an extra layer of data over the existing text and changing according to what is ‘trending’ that day. The printers never issue the same information twice.

Commonplace Studio, Jesse Howard, Tim Knapen, A Commonplace Book, 2018 — 2020. Installation view: The Work of Time, Z33. Photo: Kristof Vrancken

Commonplace Studio, Jesse Howard, Tim Knapen, A Commonplace Book, 2018 — 2020. Installation view: The Work of Time, Z33. Photo: Kristof Vrancken

Commonplace Studio, Jesse Howard, Tim Knapen, A Commonplace Book, 2018 — 2020. Installation view: The Work of Time, Z33. Photo: Kristof Vrancken

Commonplace Studio, Jesse Howard, Tim Knapen, A Commonplace Book, 2018 — 2020. Installation view: The Work of Time, Z33. Photo: Kristof Vrancken

A Commonplace Book is an open information machine that stimulates curiosity and knowledge-sharing. The work investigates how we understand, perceive and deal with time. On one side of each table is a selection of time-related objects. On the other side, a mechanical drawing machine produces excerpts, drawings, quotes or anecdotes that make us question our understanding of time. Visitors can compile their own book with the fragments available in the room and later continue filling the blank pages with their own thoughts, notes or discoveries.

More images from the exhibition:

Ecole Mondiale, Fieldstation: Time, 2020. Installation view: The Work of Time, Z33. Photo: Kristof Vrancken

Ecole Mondiale, Fieldstation: Time, 2020. Installation view: The Work of Time, Z33. Photo: Kristof Vrancken

Nelly Ben Hayoun-Stépanian, I am not a Monster. Hannah Arendt handmade doll. Photo: Kristof Vrancken

Nelly Ben Hayoun-Stépanian, I am not a Monster. Photo by Fiona Briallon

Helga Schmid, Circadian Dreams, 2020. Photo: Kristof Vrancken

Alexis Destoop, Untitled (Naji), 2017. Installation view: The Work of Time, Z33. Photo: Kristof Vrancken

Z33 House for Contemporary Art, Design & Architecture has a new exhibition wing created by architect Francesca Torzo and it is stunning:

Wing 19, a new exhibition building for Z33 by architect Francesca Torzo. Photo: Olmo Peeters

Wing 19, a new exhibition building for Z33 by architect Francesca Torzo. Photo: Gion Balthasar von Albertini

The Work of Time was curated by Ils Huygens. You’ve only got a couple of days left to visit it if you’re anywhere near Z33 House for Contemporary Art, Design & Architecture in Hasselt, Belgium.

Previously: Pazugoo, the 3D printed evil spirits of nuclear waste storage; The Nuclear Culture Source Book.