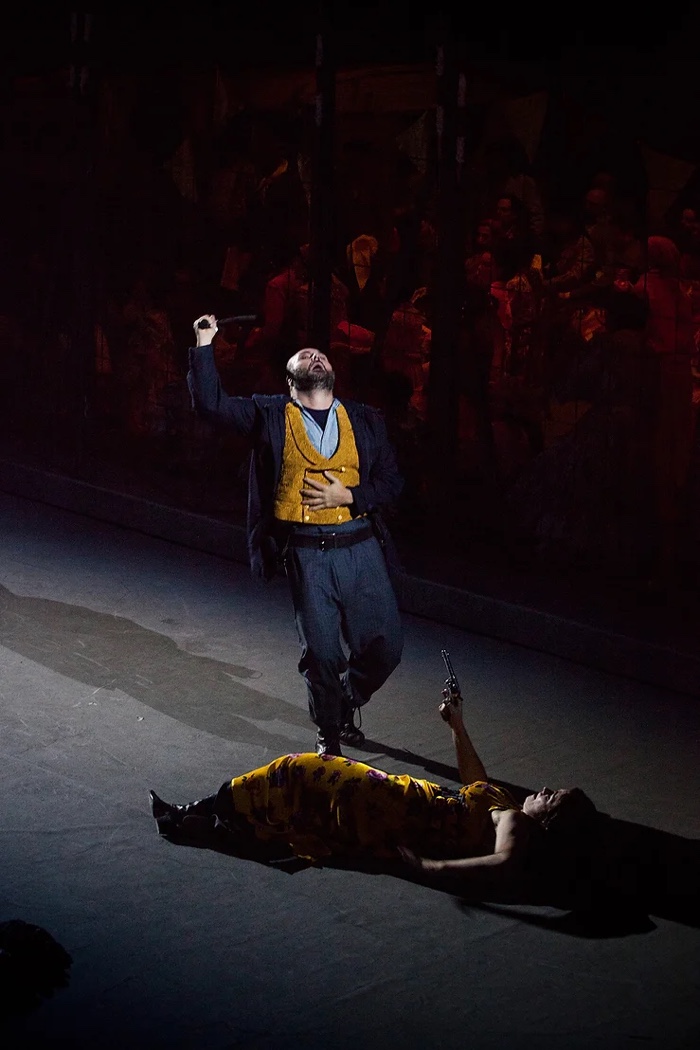

I remember the incensed headlines when the opera Carmen, directed by Leo Moscato, premiered at the Teatro del Maggio Fiorentino in 2018. In the revised final scene, Carmen -who lives in a Roma camp- is stabbed by her lover, the violent policeman Don José. However, the woman manages to grab a pistol and shoot him. With this alternative ending, Moscato wanted to express his support for Italian women killed by their partner or former partner. The idea was suggested by Cristiano Chiarot, then head of the Florence institution, who wondered: “How about a Carmen who doesn’t die? Why should we applaud when a woman is killed, in the light of what is happening at the moment?”

Carmen di Georges Bizet, directed by Leo Moscato at the Teatro del Maggio Fiorentino, 2018

Carmen di Bizet, directed by Leo Moscato at the Teatro del Maggio Fiorentino, 2018

Some people in the audience booed the final. Social media were filled with the kind of anger you only find on social media. Critics expressed their horror: art is not about morality, the opera was “violated”, the modified final was a betrayal of Bizet’s work, etc. Others applauded, believing that the way some operas present or treat feminine characters is unacceptable by today’s standards. Carmen’s gesture generated a much-needed debate about the rising rate of feminicides among opera lovers in the country. The alternative ending did not suggest that Carmen should be “sanitised” nor expurgated from any misogynist undertone. I think it was merely an experiment, a timely statement of solidarity with women victims of violence.

All the spectacles quickly sold out but I sometimes wondered if the criticisms the Director encountered had not discouraged other creative minds to take liberties with classical performances for fear that they’d be accused of being too woke, too coarse or sacrilegious.

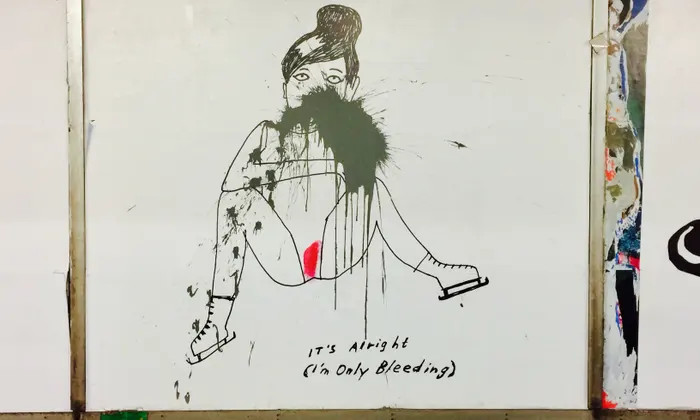

Liv Strömquist, It’s Alright (I’m Only Bleeding.) Cartoon of a menstruating woman at Slussen station in Stockholm, defaced by black paint. Photograph: Janet Carr

Eugenio Merino, Always Franco, 2012

It may look like Europe is a safe place for the freedom of artistic expression but in its most recent report, Freemuse recorded 104 violations against visual art in Europe. Sometimes these violations are easy to recognise. Such as when the influence of Beijing’s censors outside the country forces a French museum to postpone a major exhibition about Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire. When a participatory drawing of Viktor Orbán is taken off the wall of the Ludwig Museum in Budapest to the surprise of both the artist and curator. Or when writers, artists (including Jewish artists), musicians and philosophers are stripped of awards or accused of antisemitism over their stance against the oppression of Palestinians in Israel. Sometimes, however, artists and culture workers are silenced in more subdued ways. When they are self-censoring their work under pressure from right-wing populist governments, for example.

Free to Create: Report on Artistic Freedom in Europe (free PDF), published by the Council of Europe, explores the challenges European artists and cultural workers face in the practice of their right to freedom of artistic expression. Artistic freedom is a core human right that is being affected by rising political extremism, economic collapse, digital forms of disinformation and abuse, environmental disasters, protracted pandemic concerns and the return of war within Europe.

Free to Create: Report on Artistic Freedom in Europe is report but also a guide for artists and cultural actors who find themselves confronted with restrictions and interferences in their practice. It gives an overview of the institutions, organisations and support mechanisms that protect artistic expression, presents the state of artistic freedom on the continent and explores self-censorship, precarity and other under-the-radar threats that muzzle artistic practices. Free to Create also examines forms of solidarity, safe spaces for artists and suggests recommendations and ways forward.

Emin Alper, Kurak Günler, 2022

Mujeres Públicas, Cajita de fósforos, 2005. Exhibited at the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid

The author of the report is Sara Whyatt. She is a campaigner and researcher on freedom of artistic expression and human rights, notably as the director of PEN International’s freedom of expression programme for over 20 years and previously as the coordinator of Amnesty International’s Asia Research Department. In 2013, she took up freelance consultancy, working on projects for Freemuse, Culture Action Europe, PEN International and the International Freedom of Expression Exchange. She also works with UNESCO developing training programmes for governments and CSOs, as well as monitoring and reporting strategies to promote artistic freedom under the 2005 Convention.

Sara Whyatt kindly accepted to answer my questions about the background and findings of the report:

Hi Sara! Your expertise when it comes to artistic freedom is extraordinary. You are a campaigner and researcher on freedom of artistic expression and human rights, notably as the director of PEN International’s freedom of expression programme for over 20 years and previously as the coordinator of Amnesty International’s Asia Research Department. I would expect you not to be surprised by anything you read and read while working on this report. Am I wrong? Or did you encounter stories and situations you were not expecting?

I’ve been working in human rights for over 40 years. I started in 1982. I joined Amnesty International in the midst of the Cold War. Over time, especially with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, we noticed that in the Americas and in many countries around the world, there was a return to democracy. We had this feeling of euphoria but that euphoria began to fall apart, in particular following the war in Yugoslavia and in Iraq. For someone like myself who was working on human rights during the Cold War, the return of the war in Europe brings familiar old hatred, fears, divisions or the different approaches between the EU countries and Russia.

I started working on artistic freedom only in 2012 – 2013 and that was because when I was working for PEN International (which defends journalists and writers.) At the time, I was constantly getting requests from artists telling us “We’re in trouble.” “People are getting arrested. What can we do?” They had nowhere to go.

If you were a very famous artist and you were attacked or locked up, then yes, a human rights organisation would try and help you. I started wondering why lesser-known artists were not better supported and that’s why I started looking deeper into this. I came to understand that the art world is very different from the world of literature and journalism. The creative sector is more than one and artists work differently in each. If you are a performing artist, you often work collaboratively. If you’re a fine artist, you generally work alone. Artists also have different relationships with the outside world and to funding structures. So I was starting to ask whether we really understood what artistic freedom meant: was it purely about the freedom to create or was it about other fundamental rights?

Financial precarity is particularly prevalent in the arts. There is a lack of security and a reliance on institutional sponsorship, particularly for those not in the commercial sector. And if it is not a direct reliance through a grant or an award, you have to rely on your gallery, theatre or look for sponsorship. So if you are thinking about doing a play on a controversial topic or a minority issue, you are likely to rely on a theatre that is getting support from the government or from some other kind of sponsorship. The theatre may be looking over its shoulders, wondering whether or not it can risk presenting a work that might have an impact on its own funding or get a negative public reaction. The way that certain kinds of public outcry can affect your work might be direct or indirect. For example when the staff of an institution is threatened. Or when the reputation of the cultural space is damaged. That will make it less likely for an institution to take up certain types of work. The situation can be so multi-layered that sometimes it is very hard to see where the censorship happens.

There is a distinction between what happens off the radar and what is very visible, when your work is taken down or you get fined or denied a licence to perform, for example, the censorship isn’t as apparent as when works have been visibly censored such as through the courts.

You can act on legislation, you can tell a state “Please abolish this law that is penalising people for their legitimate expressions”, “Please stop arresting people under these circumstances.” But when it comes to legislating to protect economic rights or to deal with the issue of self-censorship due to wide public pressure, then I’m not even sure if there is a standard way to legislate that. Each country is so different. What can we do? I’ve been running a project for the Council of Europe where we are bringing artists together simply to exchange experiences and ideas. They have not just included artists from countries where free expression is under direct attacks such as Hungary and Poland, but also from countries where the self-censorship is more subtle, including the UK, Norway, Belgium and elsewhere. We quickly found out that there we have common issues around social, economic and public pressure on artworks.

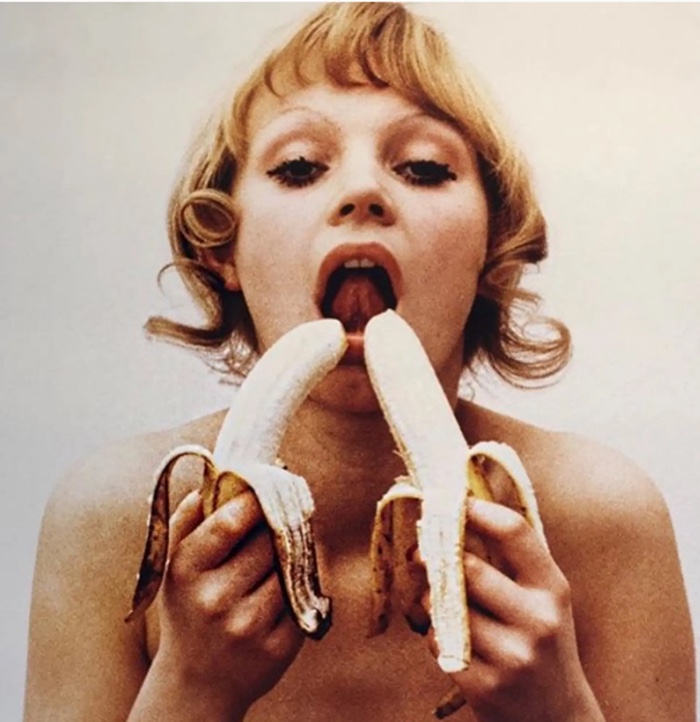

Natalia LL, Consumer Art, 1972

I always think that it all comes down to education but then again that’s another complicated field.

What surprises me is that freedom of artistic expression is not taught in universities and art schools. I have given occasional seminars, such as Goldsmiths University in London, but I do see the need for a module that would look at the threat to artistic freedom and present the legislations that promote as well as hinder creative freedom in the students’ own countries. These should include what to be thinking about when you know you are going to open an exhibition, for example, on a controversial topic, what are the legal implications, what are the protections you need to establish for the artists, the venue staff and the audience. Very important is to ask how can you have conversations with the people who might be upset by your work, how can you bring them together and explain the reasons why the artwork has been created. In countries like the UK where it is possible to speak with the police beforehand, explaining why the work has been created, identify any threats and find a way that protects against attack, rather than close the exhibition, as is the tendency among police, to find a balance between public safety and protecting artistic freedom.

The big issue is how you convince the public of the importance of artistic freedom, through the media. Public support can happen when you get controversy. Do you remember that three or four years ago in Poland, there was a 1973 video by a feminist artist featuring a woman eating a banana? The video was taken down. There was such an outcry. The response was actually very funny: the public used digital media and uploaded online all those humorous videos showing people using bananas. The work was put back up.

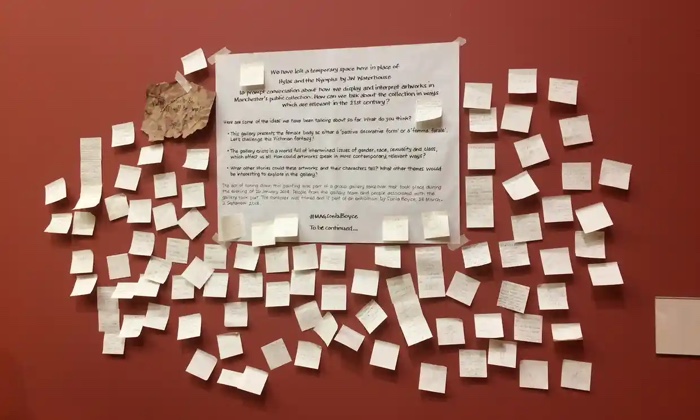

How do you support the other instances of censorship? How do you deal with controversies? It is not always very easy to do. There was an interesting incident in Manchester where the artist Sonia Boyce took down a Pre-Raphaelite painting showing young nymphs bathing. Some people were very angry, finding the censorship ridiculous. I believe the artist even received death threats. Two or three days later, it was revealed that the removal of the painting was an art intervention, Boyce wanted to start a debate about the hidden workings of museums. I am not sure that they were expecting an extreme reaction. The story reminds me of the debate around the taking down of statues: Is this the right thing to do? In the absence of memories, how do you deal with atrocity and maintain the memory? How do you deal with the tendency to censor and the reaction that follows it?

John William Waterhouse, Hylas and the Nymphs, 1896. Photograph: Manchester City Galleries

A notice in Manchester Art Gallery explains the temporary removal of John William Waterhouse’s 1896 painting Hylas and the Nymphs. The public have responded on Post-it notes. Photograph: Manchester Art Gallery

I was particularly curious about blasphemy, one of the topics your report explores. Is there really still legislation penalising blasphemy in European countries in 2023? Have artists been affected by that legislation?

There are several countries in Europe that still have blasphemy laws. In most countries, these laws are not used. Or very occasionally. You’ve got the usual suspects like Turkey that use them regularly. Poland to a certain extent does it too. But then you also find them where you wouldn’t expect them. In Switzerland, for example. In many cases, I think it is just laziness because getting legislation repealed is a pain, it takes a long time, and other priorities get in the way.

Other laws that tend to be used are the ones regarding insults and this particularly affects comedians and satirists. It is mainly insults to individuals in power, but it also extends to insults to the state for example. If you deface the flag in some countries, you could find yourself trialled or imprisoned. And even more extraordinarily another state can intervene, saying “This person in your country insulted us.” That happened to be the case in Germany with a comedian who made pretty offensive jokes about Turkish President Erdoğan. The result of that case meant that German laws were changed to ensure that this couldn’t happen again.

There are still many countries, including in Northern Europe, where you can run into trouble if you insult the monarchy. Most haven’t used these laws for decades. But it just takes one case for the atmosphere to change.

Even if some of these laws on blasphemy or insult to the state have not been used for decades, there is the danger that an autocratic state could emerge, dig up these laws and use them to suppress their critics. So a piece of work you are now developing can absolutely be fine now but tomorrow, it could put you in a difficult position.

Looking back at the blasphemy laws, there are several countries in Europe, where my work is focused at the moment, where there had been aggressive attacks by religious conservatives against artworks and writings that they see as blasphemous. Yet, recently in countries where blasphemy has been a big issue, Ireland, Greece and Malta, these laws were abolished. What is interesting is that in these counties where there had been attacks against theatres and others, the repeal of blasphemy laws has not been met with any significant backlash. This shows that there really is only a minority of people who feel so strongly about these laws and who are causing problems regarding blasphemy, religion or insults to the state. I believe that often these ideas are often instrumentalized by those in power, pandering to a small community as a means to hold onto power.

This brings us to the populist discourse and their use of “the public” when governments say “We are acting on behalf of the public and this is not what the public wants”. But who is the public exactly? It is too often a minority that populists want to instrumentals in favour of their own interests. In my view, the public is a positive force. I don’t think the public wants to see these kinds of actions. Apart perhaps from a minority, an often vociferous one because they have the ear of the government or because they are hugely present on the internet. It’s a mistake to look at social media and say that this is the true voice of public opinion. Unfortunately, these voices have an impact on government decision-making and media coverage, which in turn influences public funding, private sponsorship, etc.

You wrote the report for the Council of Europe. Do you feel that institutions, national or international, can provide meaningful assistance to artists? Do they play a different role than NGOs when it comes to supporting artists?

You wrote the report for the Council of Europe. Do you feel that institutions, national or international, can provide meaningful assistance to artists? Do they play a different role than NGOs when it comes to supporting artists?

The Council of Europe, and you can extend that to the UNESCO and to the United Nations, are big machines with burdensome bureaucracies. If you want instant results for specific critical cases then they are probably not the places to go to. Although it has to be said that the UN does have complaints “mechanisms” through which individuals can raise abuses. Relating to artistic freedom is the Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights who also issues reports on various aspects of cultural freedoms.

Working with the Council of Europe and UNESCO, these are membership organisations and in order to get a strategy, project or policy through, you need to have pretty much unanimous agreement from the member states. That can be a challenge when working in human rights and ‘naming and shaming’ is avoided. This is also why, in my reports for those institutions, I will not write something like “This is the country that has the highest number of artists in prison”. What we are looking at instead are either the trends or the positive initiatives.

When you work with institutions, you know you will be aiming for the long-term, it is about setting policies and strategies. I worked on the CoE Manifesto on the Freedom of Expression of Arts and Culture in the Digital Era, it is something that can be quoted, it is a document that can be referred to.

As for art and culture institutions, they are severely underfunded. They don’t have the resources nor the capacity to expand their remit to artistic freedom or human rights. Even if they did engage with these issues, some would be looking at the possibility of losing funding.

On the other hand, organisations such as Amnesty International don’t necessarily have that understanding of the complexities of working as an artist and the ways that artists are self-censoring or are being stopped from doing certain kinds of work. If an organisation is supporting a lot of people who are getting arrested, threatened or even killed then the fact that somebody cannot get a licence to perform in a particular space because they are on a blacklist is not going to be on the top of your agenda. Quite rightly so but it is a means of oppression that is off the radar.

Human rights organisations such as Amnesty International or the many other rights groups that are out there will take on a person who is in prison or before a court who is an artist. Generally, however, these organisations don’t have the capacity to take on the other ways that censorship happens. As for the arts and cultural institutions, the issue is that they are struggling anyway with funding and their capacity to do their core works. There are a handful of organisations that only work on artistic freedom.

There is Freemuse, Artists at Risk (AR), the Artists Rights Connection, etc. They liaise with the UN Special Rapporteur in the field of cultural rights, Alexandra Xanthaki. There are also organisations that provide places of refuge for artists at risk who have had to flee their countries, the largest and best known being the International Cities of Refuge Network (ICORN).

Every layer from international governmental to national organisations have a role in shaping global and national strategy on artistic freedom and, they also have a guidance role. They all have their strengths. The arts institutions understand, represent and know the arts sector. Human rights organisations know human rights. So you work with all of them if you work on artistic freedom. Interestingly, what is often missing is the voice of the artists themselves. All these organisations might have assumptions regarding artistic experience and artistic freedom but we are not hearing them articulated by the artists because they do not tend to have representative organisations in the same way as freedom of speech organisations do.

I am also pleased to see a lot more focus on artistic freedom in art magazines like Hyperallergic or The Arts Newspaper.

![]()

Santiago Sierra, Presos políticos en la España contemporánea, 2018

Vienna museums protested against censorship on social media and in public space by turning it into a marketing opportunity

How can individuals, and more generally society, support artistic freedom? How can we be an ally to artists?

I think it’s a difficult one because the public is only alert to artistic freedom when there is some kind of controversy. Having regular debates and features on artistic freedom would be helpful. There are quite a lot of articles on censored books. Every year, you can read articles with titles like “Books that were censored last year.” Somehow we need to get the same kind of media coverage for artists as well, with articles talking about the artworks that were censored and other issues that raise concerns. In the UK, there was a ceramic artist who made a rather large figure in a small town in Cornwall and got a negative reaction from the local church. People have to be aware that there are these pressures are happening and that we need to have more organisations that are alert and monitoring and telling the story. Sometimes, the stories are small and they cannot be compared to, for example, Shady Habash, the Egyptian filmmaker dying in prison but to keep the story going, giving it space in the art media, for that you need monitors in the country. The art world is not going to have the time and resources to do it so it is important to have organisations like Freemuse monitoring the small and the bigger stories, to gather people together to do joint petitions, or to have awareness programs for instance in art schools asking them “what do you think of this? What would you do if you were the artist?”

Philip Guston, In Riding Around, 1969

Unfortunately, even mainstream newspapers seem to dedicate less and less space to arts, unless it is novels and movies.

The problem is that the space for cultural debate has shrunk and also the expertise and the quality of arts coverage can be quite poor. That’s another reason why it is important to have a monitor for the arts because of course you can’t expect the newspapers to have a dedicated section on artistic freedom but it is important that they be alert. Journalists are always looking for another angle, they might be interested in that sort of debate. At least, that is what I would be doing if I were an advocate for artistic freedom in the UK for example. If you could get this ceramicist in Cornwall if as an organisation you could lobby well-known figures in the arts such as Grayson Perry and ask him to say something about it. That would get the attention and from there you would have the opportunity to explain that this sort of incident, and worse, is happening across Europe and the world in general.

There is a need to raise awareness of why art should be free and why even challenging art needs protection, not only in the art world, but in the wider community and the public at large.

Thanks Sara!

Related stories: Censored Art Today, János Brückner. Making visible the influence of politics on culture, Andres Serrano. Uncensored photographs, Emily Jacir’s Stazione. In Turin and uncensored this time, etc.