Video games regularly hit the news for a number of reasons. Some of them justified. Other less so. Games are accused of corrupting young people, causing spikes of violence, hosting a culture of sexism and harassment, etc. Even the extravagant production budgets that some blockbuster games command never fail to distract the conversation from the intrinsic value of game culture.

Sahej Rahal, Antraal, 2019. Exhibition view at HeK (House of electronic Arts Basel), Photo: Franz Wamhof

Mikhail Maksimov, Sanatorium Anthropocene Retreat, 2020, Video game, screenshot, Courtesy the artist

Radical Gaming – Immersion Simulation Subversion, an exhibition that opened a few days ago at HEK (House of Electronic Arts) in Basel, invites visitors to play with games that challenge gaming tropes -in particular the stereotypes of virility and the logic of competition- as well as our understanding of what it means to interact.

Boris Magrini, the curator of the show, calls these works “radical” because they offer alternative experiences of and in the virtual world. They break with the content, techniques and formal norms of the game industry and facilitate other modes of immersion and engagement.

Free from the mercantile constraints that often govern mainstream video games, the artistic games presented at HEK offer opportunities to reflect on many of the issues that have come to define our complicated cultural and historical moment: gender politics, queerness, the mysterious inner workings of artificial intelligences, racial discrimination, the excesses of financial capitalism, etc.

The interactive experiences of this avant-garde sub-genre also differ from mainstream contemporary gaming: instead of being purely adrenaline-fuelled, the rules of engagement involve meditative states, involvement of multiple senses, modified controllers, etc. They deviate from what the industry normally offers/sells. But that doesn’t mean that they are not fun, in their own, strange ways.

Here are some of the games that impressed me the most:

Theo Triantafyllidis, Pastoral (Video Game), 2019, screenshot. Courtesy the Artist and The Breeder Gallery, Athens

Theo Triantafyllidis, Pastoral (Video Game), 2019, screenshot. Courtesy the Artist and The Breeder Gallery, Athens

Theo Triantafyllidis, Pastoral (trailer), 2019

Theo Triantafyllidis, Pastoral (Video Game), 2019. Exhibition view at HeK (House of electronic Arts Basel), Photo: Franz Wamhof

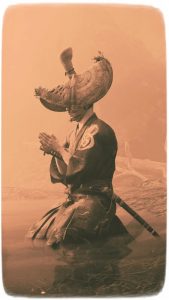

Theo Triantafyllidis, Self Portrait (Reclining Ork). Detail

Pastoral subverts the dynamics of the fantasy genre as well as one of its most common characters. Instead of waging battles against other powerful creatures bearing fearsome weapons, a beautiful transgender ork is walking across a wheat field, like a medieval knight from the ruling class fancying himself/herself as a peasant. In the background, a mythical character is playing the lute. The ork, whom the player is invited to embody, throws the player off balance: its calm gestures make it appealing and seducing while its fangs and extremely muscular silhouette render it slightly intimidating.

The world of Pastoral provides players with a restful moment. There are stacks of hay to sit on and bucolic music to enjoy. Even better (in my view): you don’t have to “interact” in order to enjoy the installation. I doubt I’ll see a work I like as much as Theo Triantafyllidis’ Pastoral this year. Sitting on the hay, watched over by a smirking tapestry version of the ork and reveling in the atmosphere of the work just filled me with pure joy.

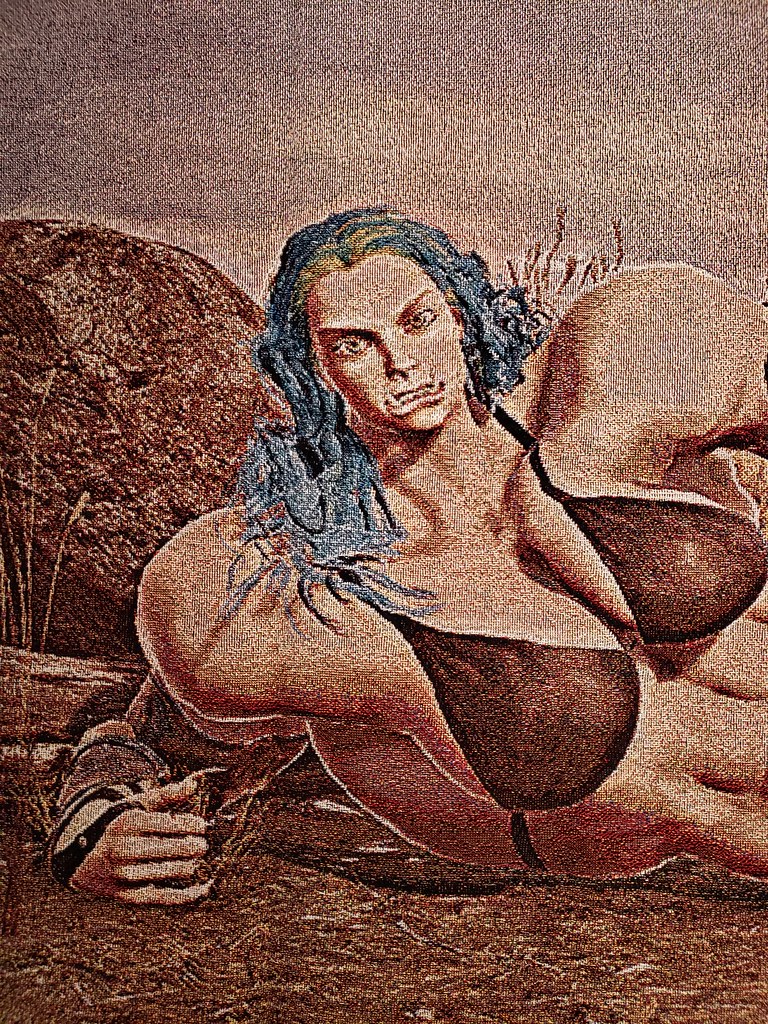

Miyö Van Stenis, Eroticissima, 2021 © Miyö Van Stenis Courtesy of the artist

Miyö Van Stenis, Eroticissima, 2021. Exhibition view at HeK (House of electronic Arts Basel), Photo: Franz Wamhof

Miyö Van Stenis, Eroticissima, 2021

MiyöVan Stenis created a kind of BDSM dungeon inside a room that people aged 16 and over can enter. This space for erotic encounters in virtual worlds attempts to break the stereotypes of the porn industry and explore sexual orientations and practices that are not targeted at the sole male clientele. I must confess I didn’t try that one. I was too self-conscious of what I would look like wearing VR goggles and manipulating the sexed-up controllers Van Stenis had designed for the installation.

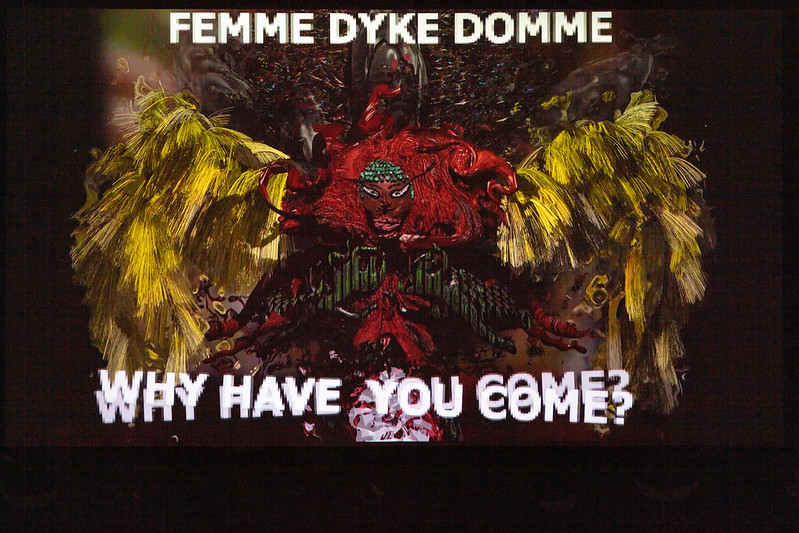

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, Resurrection Land, 2020, Browser-based video game, screenshot, Courtesy the artist

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, Resurrection Land, 2020. Exhibition view at HeK (House of electronic Arts Basel). Photo: Franz Wamhof

First-hand representation of the experiences of Black transgender people fails to appear in historical collections such as the Portico or even contemporary game culture. Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley‘s online game pays homage to them, as they are being erased from history.

A work of speculative fiction, Resurrection Land offers a digital haven for resurrected, unarchived Black trans ancestors to live out their second life. The work also seeks to address what Brathwaite-Shirley calls “trans tourism”, the inappropriate use of the experience and representation of (black) trans people. In her scenario, the more the archive is gaining in popularity, the more it becomes misused and mistreated. To prevent further appropriation of the archive (and of the often painful experiences it conveys), access to it becomes restricted. If you wish to gain access to it, you have to participate in a tournament.

To enter Resurrection Land, you are asked to indicate how close you are to the Black transgender community. This identification will determine the experience of the game, which takes place in an imaginary city ruled by a Black trans community. If you identify yourself as a member of this community, your inclusion will be greater than that of a player who identified outside of it. The game is thus both an experience that allows the Black trans community to live in a virtual space of protected communion. At the same time, it offers the possibility for players who do not identify with this community to experience exclusion firsthand. It’s a bit brutal and unpleasant but it is far less harrowing than what members of the Black trans community experience on a daily basis.

With this work Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley is also challenging the idea of what an archive can be and how they are accessed.

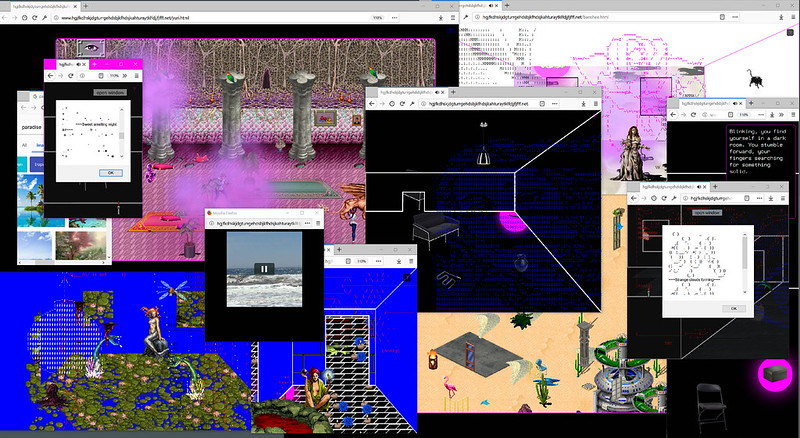

Cassie McQuater, Black Room, 2017 – ongoing, Browser-based video game, still, Courtesy the artist

Cassie McQuater, Black Room, 2017 – ongoing. Exhibition view at HeK (House of electronic Arts Basel), Photo: Franz Wamhof

A game best played in the dark, when you’re suffering from insomnia, Black Room is a feminist dungeon crawler that replicates the structure rather than the action of old school video games. In Cassie McQuater‘s version of the games, female supporting characters are recast as post-feminist heroines, questioning gender tropes and representations seasoned video game players had too often taken for granted. It’s also a fantastic journey into the aesthetics and dynamics of pre-bubble internet.

To explore and navigate the game, players have to resize the browser and manage tabs. Making windows longer or shorter, they can uncover hidden doors leading to other rooms and encounter different video game genres.

Try it if you can’t find sleep tonight! Black Room is also a fantastic journey into the aesthetics and dynamics of pre-bubble internet.

Sara Culmann, Skolkovo. The Game, 2016 – 2021, Video game, screenshot © Sara Culmann Courtesy of the artist

Sara Culmann, Skolkovo. The Game, 2016 – 2021. Exhibition view at HeK (House of electronic Arts Basel), Photo: Franz Wamhof

Sara Culmann’s open-world game depicts a postapocalyptic version of Skolkovo Innovation Center, a high tech park in Moscow.

Skolkovo. The Game is a commentary on the relationship between techno-capitalism and politics that pervades Moscow’s tech hub (just like it does elsewhere in the world.) Culmann has recreated areas of the Skolkovo Innovation Centre district ands set them in a post-apocalyptic near future. While navigating the ruins of the neighbourhood, players come across posters, objects, audio files and other media that reveal elements of corruption and financial speculation associated with the district. Over time, the secret history of the place is revealed.

With its neat, black and white aesthetics, the game subtly comments on the cult of innovation, on gentrification, on the hype of start-up culture and the uncritical faith in technology.

Leo Castañeda, Levels and Bosses, 2021, Video game, screenshot, Courtesy the artists,

Leo Castañeda, Levels and Bosses, 2021. Exhibition view at HeK (House of electronic Arts Basel), Photo: Franz Wamhof

Leo Castañeda’s Levels and Bosses is another work that made me inexplicably happy. The result of a long-term research series, the installation immerses visitors in an atmospheric game world by establishing feedback loops between the analog and the digital. Paintings are covering walls, sculptures double as pieces of furniture, video games can be played or watched as if they were pieces of video art.

More images from the show:

Lawrence Lek, Nøtel, 2016 – ongoing, HD Video, stereo sound, 19 min 30 sec, still / video game © Lawrence Lek Courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London

Lawrence Lek, Nøtel, 2016 – ongoing. Exhibition view at HeK (House of electronic Arts Basel), Photo: Franz Wamhof

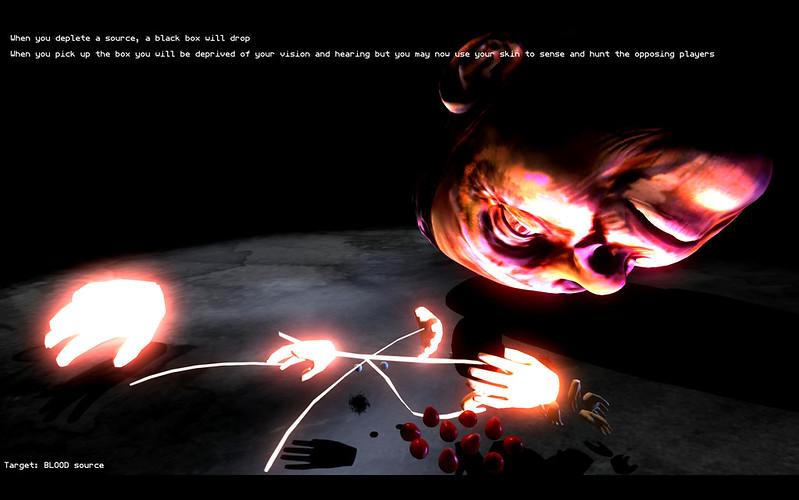

Eddo Stern (with Alex Ricket, Wilm Tobin), Darkgame 4, 2014 Computer software, Electronics, Rubber, screenshot, Courtesy of the artist

Eddo Stern (with Alex Ricket, Wilm Tobin), Darkgame 4, 2014 Computer software, Electronics, Rubber, screenshot, Courtesy of the artist

Eddo Stern (with Alex Ricket, Wilm Tobin), Darkgame 4, 2014. Exhibition view at HeK (House of electronic Arts Basel), Photo: Franz Wamhof

Sahej Rahal, Antraal, 2019, Video game and artificial intelligence simulation, screenshot © Sahej Rahal Courtesy of the artist and Chatterjee & Lal

Jacolby Satterwhite, We are in Hell when We Hurt Each Other, 2020. Exhibition view at HeK (House of electronic Arts Basel). Photo: Franz Wamhof

Debbie Ding, VOID, 2021, Video game and VR experience, screenshot © Debbie Ding Courtesy of the artist

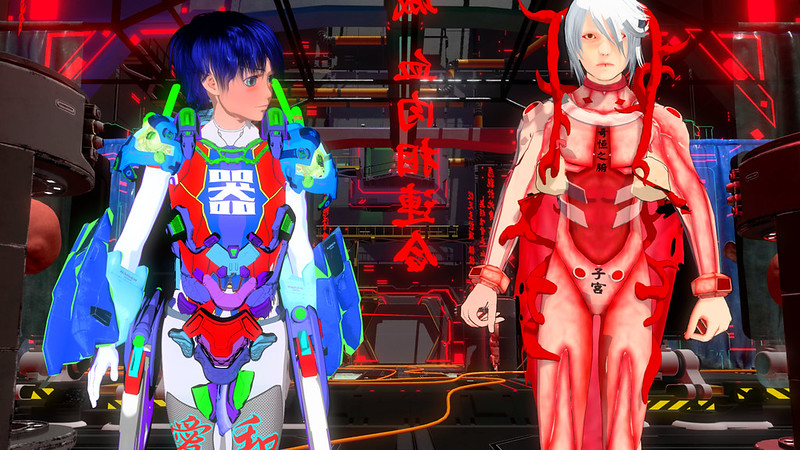

Lu Yang, The Great Adventure of Material World, 2019, Video game, screenshot © 2019 Lu Yang

Lu Yang, The Great Adventure of Material World, 2019, Video game, screenshot © 2019 Lu Yang

Lu Yang, The Great Adventure of Material World, 2019. Exhibition view at HeK (House of electronic Arts Basel), Photo: Franz Wamhof

Mikhail Maksimov, Sanatorium Anthropocene Retreat, 2020, Video game, screenshot, Courtesy the artist

Mikhail Maksimov, Sanatorium Anthropocene Retreat, 2020. Exhibition view at HeK (House of electronic Arts Basel), Photo: Franz Wamhof

Nicole Ruggiero, How The Internet Changed My Life, Franziska von Guten, 2021, 3D mixed reality (MR) portrait and installation © Nicole Ruggiero, Daniel Sabio, Dylan Banks Courtesy of the artist

Nicole Ruggiero, How The Internet Changed My Life, Mike Diva, 2021, 3D mixed reality (MR) portrait and installation © Nicole Ruggiero, Daniel Sabio, Dylan Banks

Keiken in collaboration with Obso1337, Ryan Vautier, Sakeema Crook, Wisdoms for Love 3.0, 2021, Interactive game, screenshot © Keiken Courtesy of the artist

Radical Gaming – Immersion Simulation Subversion was curated by Boris Magrini. The exhibition remains open at HEK (House of Electronic Arts) in Basel until 14 November 2021.

Previously: The feminist and the manosphere. An interview with Angela Washko, Interview with Pippin Barr, maker of witty and infuriating video games, “Universalization is a colonialist heritage.” An interview with video game curator Isabelle Arvers, Gaming Masculinity. Trolls, Fake Geeks, and the Gendered Battle for Online Culture, Play Station: Bread and Circus for the new jobless society, etc.