The Killifish lives in puddles, sometimes in the middle of a road, where trucks drive through. These habitats provide little competition for food, and are disregarded by predators, especially since water is brown and unclear. The obvious disadvantage is that puddles are highly unstable habitats. One of the strategies killifishes have developed to cope with this is to jump out of the puddle, maybe landing in a new one. Many don’t make it.

Jump technique composite

Jump technique composite

Because puddles are different, the populations evolve into new species rather quickly. The kamikaze behaviour and the multitude of subspecies have triggered the interest of a community of killifish collectors, who travel to puddles in the tropics, collect live specimens and bring them home where they will breed the fish with a self imposed ethic: the killifish must stay exactly as they were found in the puddle, and not change between generations.

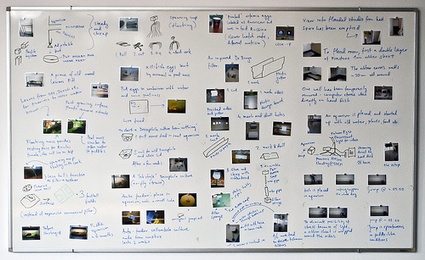

For artist Mateusz Herczka, the killifish behaviour and culture reveal a new relationship between nature and people, as if the killifish have infiltrated culture, and are now part of the cultural evolution rather than the biological. He followed the example of the killifish and infiltrated the killifish keepers community, learning, exchanging information and tactics.

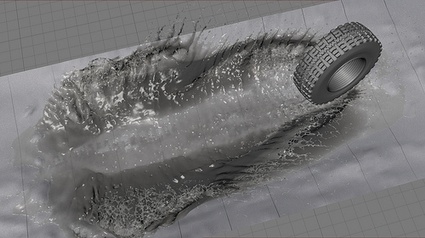

Because the way killifish jumps from one puddle to another remained to be properly documented, Herczka flooded his studio and captured this spontaneous jumping in HD video. The video material shows jumps under various conditions and still frames have been composited to show the jumping technique and the trajectory. The fish always jump in the middle of the night when nobody is around.

Reconstructing the puddle at the Verbeke Foundation

Reconstructing the puddle at the Verbeke Foundation

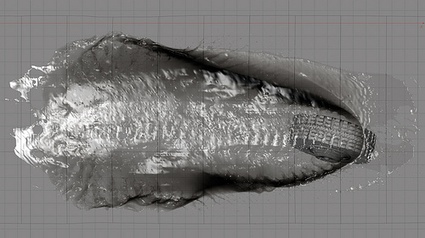

To understand how fish can survive in a puddle with trucks driving through it, the artist set up a digital simulation using software which simulates liquid, and rolled a virtual tire through a virtual puddle. Finally, an ambitious reconstruction of the puddle is being built at the Verbeke Foundation, to be completed in the next coming months. Unsurprisingly, recreating a South American puddle in an unheated Belgian space was quite a technical challenge. The huge cube of glass and metal contains a reconstruction of a puddle found in the middle of a road in Guyana, with a truck wheel rolling through it.

The Verbeke Foundation isn’t easy to reach if you don’t own a car but the result of Mateusz Herczka‘s research is documented and presented with plenty of visual material and also aquariums containing fish, worms, artemia and springtails in the exhibition Puddle Drive-Through Simulation currently open at the Verbeke Gallery in Antwerp (BE).

Diving under the puddle platform at the Verbeke Foundation

Diving under the puddle platform at the Verbeke Foundation

I hope to be able to visit the show when i’m in Belgium next month. In the meantime, i asked Mateusz to answer my many questions:

How did you first encounter the Killifish? But even more importantly, what made you want to spend more than 3 years working with them?

There is a two-floor basement near my studio in Stockholm. The upper floor was a club for mini-z model car racing. A steel door leading to the lower floor says “Södermalms Akvarieaffär, kom in och titta”, (South-side’s aquarium shop, come in and have a look). One day I needed glass and thought maybe they could sell me some. Upon entering, I realized this is not a regular aquarium shop. The atmosphere was somewhere in between a laboratory, and a computer club I belonged to as a teenager. Passing a few normal looking aquariums and some merchandise, I turned a corner and saw rows of murky aquariums with carefully written labels showing Latin names and some kind of codes. The fish didn’t look like any I had seen in other shops. Homemade devices, bubbling liquids in plastic bottles, cultures of little worms and jumping things.

I was approached by a guy who said “Amazing, isn’t it? Janne only works with nature forms.” He indicated the owner, Jan Wester, who turned out to be an architect devoting his life to killifish, a warm and friendly guy who loves to talk about killifish and keeping techniques. His strict ethic of fish origin and his refusal to stock more popular “plastic fish” turns a lot of customers away. The shop is his “fishroom”. I visited him several times and listened to his stories. Later, I met other killi keepers around Europe, and found a rich scene on the internet.

What intrigued me was the complexity and level of involvement with what appears to be an insignificant fish species. Then I found the Jim’s Basement Floor anecdote, and started to remember fragments of literature I read. A story by Polish SciFi writer Stanislaw Lem, describing a planet where the government decided that the fish was the most noble state of being, so the water level is raised a little every year. Or various books where someone travels to the jungle, it starts to rain, and “suddenly there are fish on the ground”.

I started to wonder if these fish are quietly infiltrating culture – on a grassroots level in people’s basements, in stories suggesting a merging of people/fish habitats. This links to the discussion of a possible end of biological evolution – the new evolution being cultural, the new fitness parameter being adaptability in culture. I was wondering if I, an artist, could bring something new to the killifish scene, but also infiltrate the killifish scene into the art community, to push the killifish even further into the realms of culture, using strategies from both science and art.

Composite from video stills to show the jump trajectory

Composite from video stills to show the jump trajectory

I was also intrigued by the existence of a killikeeper community. Who are they? Is there anything that sets them apart from other fish hobbyists? Did they give you any feedback about your Killifish art projects?

The people I met are all professionals in different fields. They are spread around the globe, communicate via internet, send eggs to each other via airmail, and sometimes meet at conventions. Some of them make field trips to the tropics, looking for fish in puddles, ditches, etc. Specimens are brought home for breeding and preservation in the fishroom. This requires dedication and ingenuity – the fish are quirky, jump out of the aquarium, some subspecies are very short-lived and lay eggs that need to be dried and re-hydrated several times. The community is bristling with clever technical DIY solutions that enables maintenance of a large aquarium count, live food culture in the everyday home environment, ecological “balanced” aquaria, automation, etc. A major contrast to domesticated species from the aquarium shop.

After speaking to several killifish keepers, and observing their interaction with the fish, I get an impression of a special kind of relationship with nature. Not keeping animals as pets, decoration, utility or food, but bringing content and meaning to your free time by actively interacting with an animal population, shunning commercial products in lieu of Do It Yourself methodology. It is especially interesting to note their killifish breeding ethic, to preserve the population as close as possible to the nature form, the exact look and behaviour of the original fish in the puddle. The community arranges regular contests where keepers show fish which are judged specifically on the nature form criteria. In the case of some subspecies, the original habitats are gone. The preservation ethic allows such populations to continue their existence in somebody’s fishroom.

Laboratory to Ascertain Plausibility of Jim’s Basement Floor Anecdote, 2009

Laboratory to Ascertain Plausibility of Jim’s Basement Floor Anecdote, 2009

I have received a lot of help and feedback from the killi community. When showing Laboratory to Ascertain Plausibility of Jim’s Basement Floor Anecdote, local killi keepers helped to arrange fish and care for them, and the installation became something of a meeting place. Many are intrigued by my video films showing the killifish jumping behavior, which was common knowledge but never properly documented. These films attract attention from the art community, but also bring something new to the killi keepers.

The Verbeke Gallery in Antwerp

The Verbeke Gallery in Antwerp

The Verbeke Foundation

The Verbeke Foundation

The Verbeke Gallery in Antwerp

The Verbeke Gallery in Antwerp

The introductory text of the catalogue, written by Simon Delobel, explains that you gave your aquariums and fish to a shop because “keeping killifishes at home or in his studio would have meant losing the artistic aspect of his creative activity.” Can you tell us the reason for that?

When working with a project, my artistic strategies are based on theoretical research, but most importantly to “walk the walk and talk the talk”. In this case, I had to learn the methods of killikeeping by maintaining some populations in my studio, their way. I discovered that it was extremely interesting, and found myself wanting to try some new killifish species, different methods, contacting some guy i Canada to get eggs from a rare Rivulus type…

After about a year, my studio was filling up with aquariums – I was “bitten by the bug”. This is very relevant to the whole story – the killifish seem to combine just the right elements of complexity and accessibility to create and maintain interest with almost anybody. After an exhibition in Spain, I heard that one of the personnel had started to keep killifish. So one side effect of this project has been to promote a specific and positive model of interaction between people and nature. But as an artist I need to retain objectivity, and so I gave all my killifish away.

Like some of your other works, this installation navigates between art and science. You asked for the advice of experts in various disciplines, read numerous articles and watched scientific videos in order to make your own as scientific as possible. Nowadays many people see art and science as two radically different fields. But what do they have in common for you? Why do you find that they can be intertwined? What does this intimate flirting with science (or amateur science) brings to your art practice?

Like some of your other works, this installation navigates between art and science. You asked for the advice of experts in various disciplines, read numerous articles and watched scientific videos in order to make your own as scientific as possible. Nowadays many people see art and science as two radically different fields. But what do they have in common for you? Why do you find that they can be intertwined? What does this intimate flirting with science (or amateur science) brings to your art practice?

There are many answers, not always coherent. In art school, I learned how to make things look like art, and art theory as an analysis tool for the work – there were no new media or art/science programs at the time. But artistic practice for me has always kept one leg in the process of discovery, both digital and wetware. In the 90’s I participated in the generative graphics scene, which consisted of people publishing strange quicktime videos on the budding internet, projecting live graphics from laptops in artsy clubs, hacking video games to crash in an interesting way etc. This was very exciting and relevant stuff but the art world had no idea what to do with it, there were no proper contexts, and most of the material is gone today, the computers outdated, the operating systems deprecated.

I decided to abandon art theory as an anaysis tool for my work, and started to look for alternative artistic strategies. Having studied with conceptual artist Dick Raaijmakers in Den Haag, I started formulating projects that provided some kind of answer to questions. This in contrast to the common saying that “science provides answers, art provides questions”. To provide answers, you have to look for them, which means genuinely trying to understand certain literature, formulating and recreating experiments, careful documentation and so on. And when embarking on a research journey, the mind has to be open for what comes out – the semiotics of the work don’t always look like art.

Another strong component is Do It Yourself – I know scientists as discussion partners, but I prefer to work in such a way that I can do most of the initial work myself. This is one reason for plugging into communities, which often accumulate large bodies of informal knowledge of very high quality. Lately, I’m looking for ways to bring the DIY aspect to the audience as well. I’m increasingly considering the DIY aspect to be crucial to survival not only of art, but of the post-technological society, because it breaks down peoples dissociation with nature, science and technology, and connects them to the artistic experience.

For example, my Open Out Of Body Experience project uses recent science to let people experience an artificially induced OOBE, video game style, in a DIY format. The discussions that come from these sessions show an urgent need for problematization of the avatar concept, which recently cemented itself in our culture but whose morality has never really been discussed at street level. Or to take the point even further – if there was a DIY nuclear plant, Fukushima would have looked different today.

The art & science moniker is a buzzword that goes around right now, and I’m not sure what to make of it. I am an artist who tries to understand things going on right now in the real world, using methods which can also be found in the scientific tradition. The process of understanding leaves a trail of images, objects, videos and ideas, which I call art. I get the question all the time: is your work art or science? Good question, but I don’t have a good answer without engaging into a long discussion about semiotics….

A group of visitors checking out the work in progress at the Verbeke Foundation

A group of visitors checking out the work in progress at the Verbeke Foundation

Does this project mark the end of your artistic relationship with killifishes or do you think you haven’t quite finished exploring their world?

Does this project mark the end of your artistic relationship with killifishes or do you think you haven’t quite finished exploring their world?

Returning to the nature form preservation concept of the killifish community, there is a tendency of aquarium bred species to become more beautiful. Not because of selective breeding by keeper (actually the keepers are very selective to prevent this). It’s a principle in any species that relies on display for sexual selection – the more beautiful, the more visible for predators – which increases overall fitness. I’m planning a project inspired by the citizen science model which documents such change over several generations. Interestingly, a specific population from one subspecies of killifish seems to have abandoned display selection for another principle – forced copulation. Basically a rapist killifish. Further research is necessary to fully ascertain what’s going on. But it’s not certain if the research will lead me elsewhere. We’ll see.

Thanks Mateusz!

PDF of the catalogue. More images of the work in progress at the Verbeke Foundation.

You can see Puddle Drive-Through Simulation at the Verbeke Gallery in Antwerp (BE) until 20th October 2011.