Oceans, edited by writer and art historian Pandora Syperek and art historian Sarah Wade. Published by MIT Press.

Oceans is part of a Whitechapel Gallery series titled The Documents of Contemporary Art. Each volume focuses on a specific subject or body of writing that has been of key influence in contemporary art.

This anthology presents the work of artists and writers who address the ocean as a major actor in artistic and curatorial practices. Many of the essays look at oceans as a dynamic force that can be nurturing, awe-inspiring or sinister. Oceans are part of who we are. They carry the same saltwater as the one that runs through our bodies. They are capable of flooding, rising and raging in unprecedented ways as the climate emergency unfolds. Oceans are also the habitats of wondrous creatures, some we know, others that stubbornly hide from us, some we have declared intelligent and others we dismiss.

The book navigates both spaces that appear familiar and spaces that remain far away from our land-bound existences. It offers readers multiple opportunities to embrace plurality, divergences and utter strangeness.

Oceans contains dozens of essays by artists, art critics, curators and thinkers. It’s eclectic, entertaining, deep and packed with surprises. Here’s a small selection of the ideas and artworks I discovered along its pages:

Guy Ben-Ner, Moby Dick, 2000

Shuvinai Ashoona, Composition (Attack of the Tentacle Monsters), 2015. Photo: Feheley Fine Arts

Tarralik Duffy explains the impact that the arrival of whale ships had on the imagination of Inuits. Once seen as alien invaders, the ships are now welcome as they bring in much-needed supplies from the outside world.

Brian Jungen, Cetology, 2002. Photo: Trevor Mills/Vancouver Art Gallery

Matthew Higgs interviews Brian Jungen about the wonders and dangers of marine habitats. His large sculptures of whale skeletons, made of mass-produced plastic garden furniture, allude to the uncontrollable pollution threatening the survival of the sea’s biggest mammal.

Shimabuku, Sculpture for Octopuses: Exploring for Their Favorite Colours, Aquarium in Kobe (film still), 2019

Shimabuku, Sculpture for Octopuses: Exploring for Their Favorite Colours, Aquarium in Kobe (film still), 2019

One of my favourite texts is by Shimabuku who wrote a kind of journal that narrates his adventures with octopuses and the special relationship he developed with them over the years.

Marcus Coates, Finfolk, 2003 (excerpt)

Ron Broglio explains how Marcus Coates’s work reexamines folklore about amphibious creatures who change form and interact with humans. According to Scottish folklore, the finfolk are mysterious shape-shifters who travel from their underwater world onto land in order to cause havoc.

Anthropologist Stefan Helmreich, author of Alien Ocean, describes how marine biologists use the figure of the alien when they depict the unfamiliar universe of marine microbes, the foreignness of invasive species and the possibility that marine microbes might serve as models for extraterrestrial life forms.

Vampyroteuthis infernalis. Photo: © 2004 MBARI

Vilém Flusser and Louis Bec‘s 1987 treatise about the Vampyroteuthis infernalis, a cephalopod that inhabits the abysses of the sea, was an essay I will read again and again with joy.

We would not survive in the Vampyroteuthis infernalis habitat and, they write, when we hold its relatives captive in aquaria, they kill themselves by devouring their own arms. The main difference between the vampyroteuthis and us lies in art. “The difference between our art and that of the vampyroteuthis,” they explain, “is this: whereas we have to struggle against the stubbornness of our materials it has to struggle against the stubbornness of its fellow vampyroteuthes. Just as our artists carve marble, vampyroteuthic artists carve the brains of their audience. Their art is not objective but intersubjective: it is not in artefacts but in the memories of others that it hopes to become immortal.”

Jean Painleve, Scene from Acera or The Witches’ Dance, 1972.

Ralph Rugoff wrote a brilliant text that explores how, in his work, filmmaker Jean Painlevé plays up minor similarities of appearance between certain sea creatures and humans.

Allan Sekula, Fish Story, 1995

Allan Sekula argues that the model of containerised, automated and odour-free harbours challenges the belief that computers and telecommunications are the sole engines of the third industrial revolution.

Heba Y. Amin, Operation Sunken Sea, 2018-ongoing

Tacita Dean, Teignmouth Electron, 1999

Tacita Dean writes about the extraordinary story of Donald Crowhurst. In 1968–69, the British businessman and amateur sailor competed in a single-handed, round-the-world yacht race. Mid-way into the Atlantic, Crowhurst realised he would abandon the race. However, he reported false positions and faked the circumnavigation.

By June 1969, when Crowhurst’s fabricated Journey collided with his real position in the Atlantic. As he resumed radio communication, he learnt that he was winning the race. By that time, however, Crowhurst was beginning to suffer from ‘time-madness’, a familiar problem for sailors whose only way of locating their position is through meticulous time-keeping. His logbooks, found after his disappearance, suggest that the stress he was under and the associated psychological deterioration may have driven him to commit suicide.

The Estate of Bas Jan Ader / Mary Sue Ader Andersen, 2019 / The Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jan Verwoert writes about Bas Jan Ader, a young artist who disappeared at sea in 1975 while attempting to sail from the east coast of the United States to Europe as part of a project titled In Search of the Miraculous.

The solitary endeavour turned Bas Jan Ader into the romantic figure of the tragic hero who met his death while sailing surrounded by sublime nature.

Klara Hobza, Diving Through Europe, Part 1: Introduction, 2012. Photo

Klara Hobza talks to Bergit Arends about her experience of in diving through Europe’s rivers, canals and harbours from the North Sea to the Black Sea. The artist shares stories about the encounters she makes along the way, the dangers posed by finding a huge container ship pushing straight towards you and the exercise of eating a banana underwater.

Betty Beaumont, Ocean Landmark, 1978–80

Betty Beaumont collaborated with a team of scientists and engineers on an artwork that recycles 500 tons of processed coal waste into a habitat for fish. The underwater piece on the floor of the Atlantic transforms a potential pollutant into a lush underwater garden that has grown into a new, constantly evolving ecosystem.

Saskia Olde Wolbers, Pfui – Pish, Pshaw / Prr, 2017

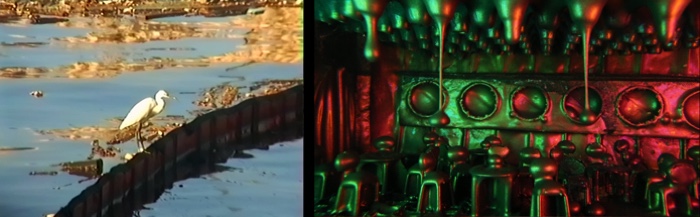

Saskia Olde Wolbers’ film Pfui – Pish, Pshaw/Prr deals with the urgent business of marine oil spills and fossil fuel’s continuing threat to the environment. The work gives voice to Mr Theodosis Alifrangis, the longest-serving worker of a Greek toxic waste management company, who unofficially filmed over 20 years of emergency callouts on his camcorder.

Isabella Rossellini, Elephant Seal – Green Porno Season 2

Sarah Wade looks at the role that Isabella Rossellini’s Green Porno vignettes, with their mix of playfulness and scientific rigour, can play in making people want to protect wildlife.

John Akomfrah, Vertigo Sea, 2015. Photo: © Smoking Dogs Films

John Akomfrah’s Vertigo Sea inspired T.J. Demos to write about the importance of holding historical failings within the realm of visibility – so that the creation of future alternatives will take them into account.

Dorothy Cross, Jellyfish Lake (video still), 2002

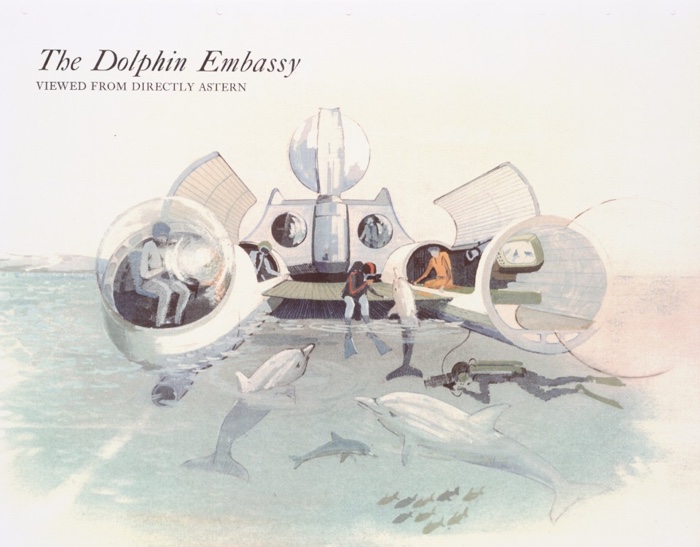

Ant Farm, The Dolphin Embassy, 1974

Related stories: Prospecting Ocean. The extractivist Wild West, Forensic Oceanography, investigating the militarised border regime in the Mediterranean, Turning human tears into a mini marine ecosystem, Heard by the Deep. How sound artists reveal the challenges encountered by the underwater world, “Have we met?” A multispecies approach to the planet, Tales from the Crust. Portraits of extractive violence and resistance, Life on a Post-Water planet, etc.