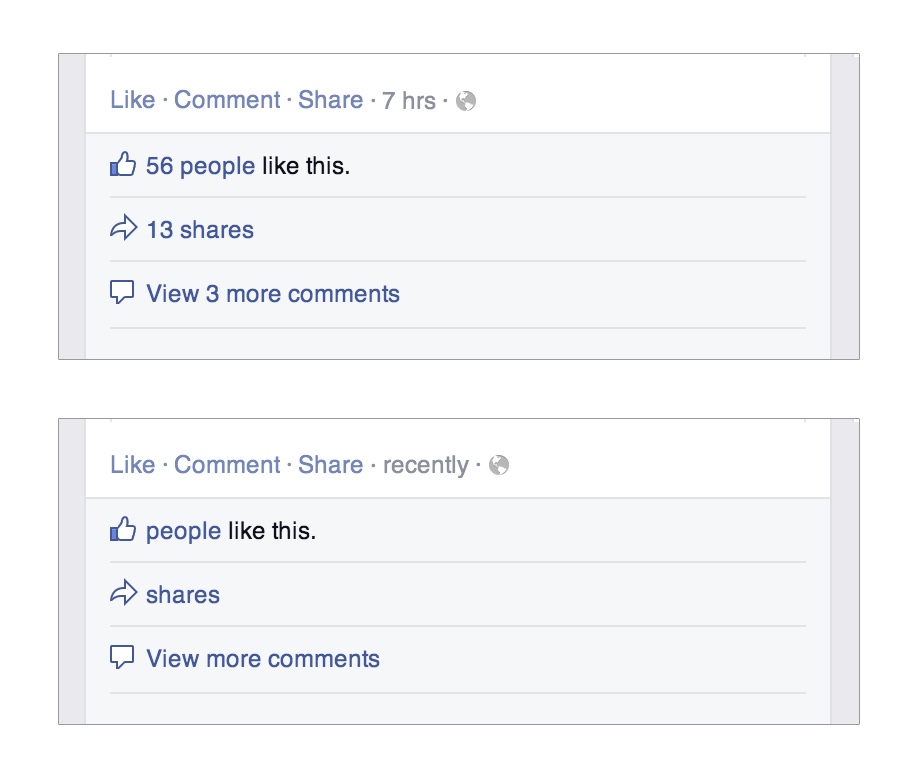

Ben Grosser, Go Rando, 2017

At a time when truth is treated as a polymorph and malleable commodity, when half of your country seems to live in another dimension, when polls are repeatedly proved wrong, when we feel more betrayed and crushed than ever by the result of a referendum or a political election, it is easy to feel disoriented and suspicious about what people around us are really thinking.

Blinding Pleasures, a group show curated by Filippo Lorenzin at arebyte Gallery in London invites us to ponder on our cognitive bias and on the mechanisms behind the False Consensus effect and the so-called Filter Bubble. The artworks in the exhibition explore how we can subvert, comprehend and become more mindful about the many biases, subtle manipulations and functioning of the mechanisms that govern the way we relate to news and ultimately to our fellow human beings.

Ben Grosser, Go Rando (Demonstration video), 2017

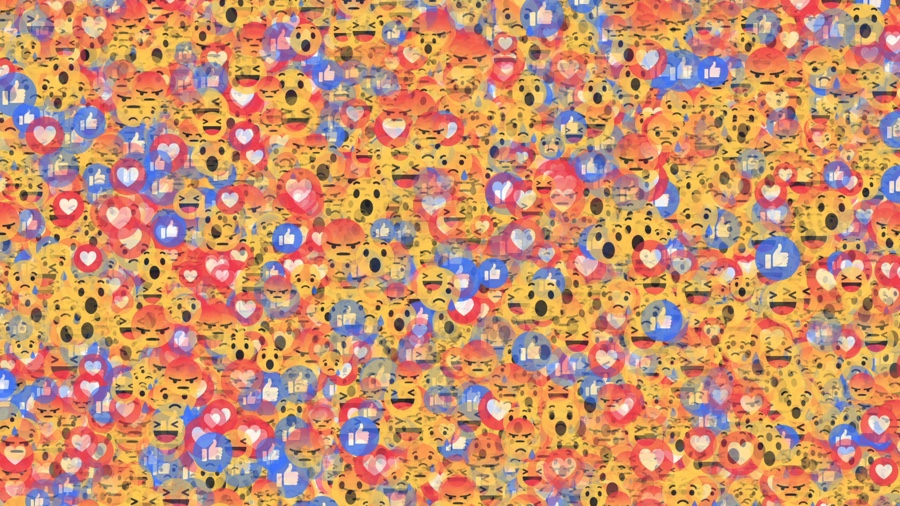

One of the pieces premiering at arebyte is Go Rando, a brand new browser extension by Ben Grosser that allows you to muddle your feelings every time you “like” a photo, link or status on Facebook. Go Rando will randomly pick up one of the six Facebook “reactions”, leaving thus your feelings and the way you are perceived by your contacts at the mercy of a seemingly absurd plug-in.

The impetus behind the work is far more astute and pertinent than it might seem though. Every “like”, every sad or laughing icon is seen by your friends but also processed by algorithms used for surveillance, government profiling, targeted advertising and content suggestion. By obfuscating the limited number of emotions offered to you by Facebook, the plug-in allows you to fool the platform algorithms, perturb its data collection practices and appear as someone whose feelings are emotionally “balanced”.

If you want to have a go, installing Go Rando on your browser is a fairly straightforward task. And don’t worry, the extension also allows you choose a specific reaction if you want to.

Grosser has been critically exploring, dissecting and perverting facebook mechanisms for a number of years now. His witty artworks become strangely more relevant with each passing year, as facebook gains even more popularity, both in number, influence and importance.

I caught up with Ben right after the opening of the Blinding Pleasures show:

Hi Ben! Your latest work, Go Rando, randomly assigns Facebook users an ‘emotion’ when you click “Like”. I hate to admit it but I’m not brave enough to use Go Rando. I’d feel too vulnerable and at the mercy of an algorithm. Also, I’d be too worried about the way my contacts would judge the assigned reactions. “Would I offend or shock anyone?” Are you expecting that many people will be as coward as I am? And more generally, what are you expecting people to discover or reflect upon with this work?

As users of Facebook I’d say we are always—as you put it—“at the mercy of an algorithm.” With Go Rando I aim to give users some agency over which algorithm they’re at the mercy of. Are they fully subject to the designs Facebook made available, or are they free to deviate from such a prescribed path? Because Go Rando’s purpose is to obfuscate one’s feelings on Facebook by randomly choosing “reactions” for them, I do expect some (many?) will share your concerns about using it.

However, whether one uses Go Rando or not, my intention for this work is to provoke individual consideration of the methods and effects of emotional surveillance. How is our Facebook activity being “read,” not only by our friends, but also by systems? Where does this data go? Whom does it benefit? Who is made most vulnerable?

With this work and others, I’m focused on the cultural, social, and political effects of software. In the case of Facebook, how are its designs changing what we say, how we say it, and to whom we speak? With “reactions” in particular, I hope Go Rando gets people thinking about how the way they feel is being used to alter their view of the world. It changes what they see on the News Feed. Their “reactions” enable more targeted advertising and emotional manipulation. And, as we’ve seen with recent events in Britain and America, our social media data can be used to further the agendas of corporate political machines intent on steering public opinion to their own ends.

Go Rando also gives users the possibility to select a specific reaction when they want to. That’s quite magnanimous. Why not be more radical and prevent users from intervening on the choice of emotion/reaction?

I would argue that allowing the user occasional choice is the more radical path. A Go Rando with no flexibility would be more pure, but would have fewer users. And an intervention with fewer users would be less effective, especially given the scale of Facebook’s 1.7 billion member user base. Instead, I aim for the sweet spot that is still disruptive yet broadly used, thus creating the strongest overall effect. This means I need to keep in mind a user like you, someone who is afraid to offend or shock in a tricky situation. The fact is that there are going to be moments when going rando just isn’t appropriate (e.g. when Go Rando blindly selects “Haha” for a sad announcement). But as long as the user makes specific choices irregularly, then those “real” reactions will get lost in the rando noise. And once a user adopts Go Rando, one of its benefits is that they can safely get into a flow of going rando first and asking questions later. They can let the system make “reaction” decisions for them, only self-correcting when necessary. This encourages mindfulness of their own feelings on/about/within Facebook while simultaneously reminding them of the emotional surveillance going on behind the scenes.

Opening of Blinding Pleasures. Photo by Graham Martin for arebyte gallery

Opening of Blinding Pleasures. Photo by Graham Martin for arebyte gallery

Go Rando is part of arebyte Gallery’s new show Blinding Pleasures. Could you tell us your own view on the theme of the exhibition, the False Consensus effect? How does Go Rando engage in it?

With the recent Brexit vote and the US Presidential election, I think we’ve just seen the most consequential impacts one could imagine of the false consensus effect. And even though I’m someone who was fully aware of the role of algorithms in social media feeds, I (and nearly everyone else I know) was still stunned this past November. In other words, we thought we knew what the country was thinking. We presumed that what we saw on our feeds was an accurate enough reflection of the world that our traditional modes of prediction would continue to hold.

We were wrong. So why? In hindsight, some of it was undoubtedly wishful thinking, hoping that my fellow citizens wouldn’t elect a racist, sexist, reality television star as President. But some of it was also the result of trusting the mechanisms of democracy (e.g. information access and visibility) to algorithms designed primarily to keep us engaged rather than informed. Facebook’s motivation is profit, not democracy.

It’s easy to think that what we see on Facebook is an accurate reflection of the world, but it’s really just an accurate reflection of what the News Feed algorithm thinks we want the world to look like. If I “Love” anti-Trump articles and “Angry” pro-Trump articles, then Facebook gleans that I want a world without Trump and gives me the appearance of a world where that sentiment is the dominant feeling.

Go Rando is focused on these feelings. By producing (often) inaccurate emotional reactions, Go Rando changes what the user sees on their feed and thus disrupts some of the filter bubble effects produced by Facebook. The work also resists other corporate attempts to analyze our “needs and fears,” like those practiced by the Trump campaign. They used such analyses to divide citizens into 32 personality types and then crafted custom messages for each one. Go Rando could help thwart this kind of manipulation in the future.

The idea of a False Consensus effect is overwhelming and it makes me feel a bit powerless. Are there ways that artists and citizens could acknowledge and address the impact it has on politics and society?

It is not unreasonable to feel powerless given the situation. So much infrastructure has been built to give us what (they think) we want, that it’s hard to push back against. Some advocate complete disengagement from social media and other technological systems. For most that’s not an option, even if it was desirable. Others develop non-corporate distributed alternatives such as Diaspora or Ello. This is important work, but it’s unlikely to replace global behemoths like Facebook anytime soon.

So, given the importance of imagining alternative social media designs, what might we do? I’ve come to refer to my process for this as “software recomposition,” treating sites like Facebook, Google, and others not as fixed spaces of consumption and interaction but as fluid spaces of manipulation and experimentation. In doing so I’m drawing on a lineage of net artists and hacktivists who use existing systems as their primary material. In my case, such recomposition manifests as functional code-based artworks that allow people to see and use their digital tools in new ways. But anyone—artist or citizen—can engage in this critical practice. All it takes is some imagination, a white board, and perhaps some writing to develop ideas about how the sites we use every day are working now, and how small or big changes might alter the balance of power between system and user in the future.

Ben Grosser, Go Rando, 2017

Ben Grosser, Go Rando, 2017

I befriended you on Facebook today not just because you look like a friendly guy but also because I was curious to see how someone whose work engages so critically and so often with Facebook was using the platform. You seem to be rather quiet on fb. Very much unlike some of my other contacts who carry their professional and private business very openly on their page. Can you tell us about your own relationship to Facebook? How do you use it? How does it feed your artistic practice? And vice-versa, how maybe some projects you developed have had an impact on the way you use Fb and other social platforms?

When it comes to Facebook I’d say I’m about half Facebook user and half artist using Facebook.

I start with the user part, as many of my ideas come from this role. I use Facebook to keep up with friends, meet new people, follow issues—pretty normal stuff. But I also try to stay hyper-aware of how I’m affected by the site when using it. Why do I care how many “likes” I got? What causes some people to respond but others to (seemingly) ignore my latest post?

When these roles intersect, Facebook becomes a site of experimentation for me. I’m constantly watching for changes in the interface, and when I find them I try to imagine how they came to be. What is the “problem” someone thought this change is solving? I also often post about these changes, and/or craft tests to see how others might be perceiving them.

A favorite example of mine is a post I made last year:

“Please help me make this status a future Facebook memory.”

Nothing else beyond that, no explanation, no instruction. What followed was an onslaught of comments that included quotes such as: “I knew you could do it!!” or “great news!” or “Awesome! Congrats!” or “You will always remember where you were when this happened.” In other words, without discussion, people had an instinct about what kinds of content might trigger Facebook in the future to recall this post from this past. These kinds of experiments not only help me think about what those signals might be, but also illustrate how many of us are (unconsciously) building internal models about how Facebook works at the algorithmic level. Because of this, much of my work has a collaborative nature to it, even if those collaborations aren’t formal ones.

Ben Grosser, Facebook Demetricator (demonstration video), 2012-present

Do you know if some people have started using or at least perceiving Facebook and social media practices in general differently after having encountered one of your works?

Yes, definitely. Because some of my works—like Facebook Demetricator, which removes all quantifications from the Facebook interface—have been in use for years by thousands of people, I regularly get direct feedback from them. They tell me stories about what they’ve learned of their own interactions with Facebook as a result, and, in many cases, how my works have changed their relationship with the site.

Some of the common themes with Demetricator are that its removal of the numbers on Facebook blunts feelings of competition (e.g. between themselves and their friends), or removes compulsive behaviors (e.g. stops them from constantly checking to see how many new notifications they’ve received). But perhaps most interestingly, Demetricator has also helped users to realize that they craft rules for themselves about how to act (and not act) within Facebook based on what the numbers say.

For example, multiple people have shared with me that it turns out they have a rule for themselves about not liking a post if it has too many likes already (say, 25 or 50). But they weren’t aware of this rule until Demetricator removed the like counts. All of the sudden, they felt frozen, unable to react to a post without toggling Demetricator off to check! If your readers are interested in more stories like this, I have detailed many of them in a paper about Demetricator and Facebook metrics called “What Do Metrics Want: How Quantification Prescribes Social Interaction on Facebook,” published in the journal Computational Culture.

Ben Grosser, Facebook Demetricator, 2012-present

Ok, sorry but I have another question regarding Facebook. I actually dislike that platform and tend to avoid thinking about it. But since you’re someone who’s been exploring it for years, it would be foolish of me to dismiss your wise opinion! A work like Facebook Demetricator was launched in 2012. 5 years is a long time on the internet. How do you feel about the way this project has aged? Do you think that the way Facebook uses data and the way users experience data has evolved over time?

I have mixed feelings about spending much of my last five years with Demetricator. I’m certainly fortunate to have a work that continues to attract attention the way this one does. But there have been times—usually when Facebook makes some major code change—when I’ve wished I could put it away for good! Because Facebook is constantly changing, I have to regularly revise Demetricator in response or it will stop functioning. In this way, I’ve come to think of Demetricator as a long-term coding performance project.

Perhaps the best indicator of how well Demetricator has aged is that it keeps resurfacing for new audiences. Someone who had never heard about it before will find the work and write about its relationship to current events, and this will create a surge of new users and attention. The latest example is Demetricator getting discussed as a way of dealing with post-election social media anxiety in the age of Trump.

In terms of Facebook’s uses of and user experiences with data over time, there’s no question this has evolved. People have a lot more awareness about the implications of big data and overall surveillance post-Snowden. The recent Brexit and US election results have helped expand popular understandings of concepts like the filter bubble. And I would say that, while perhaps not that many people are aware of it, many more now understand that what we see on Facebook is the result of an algorithm making content decisions for us. At the same time, Facebook continues to roll out new methods of quantifying its users (e.g. “reactions”), and these are not always discussed critically on arrival, so there’s plenty of room for growth.

I find the way you explore and engage with algorithms and data infrastructures fascinating, smart but also easy to approach for anyone who might not be very familiar with issues related to algorithm, data gathering, surveillance, etc. There always seem to be several layers to your works. One that is easy to understand with a couple of sentences and one that goes deeper and really questions our relationship to technology. How do you ensure that people will see past the amusing side of your work and immerse themselves into the more critical aspect of each new project (if that’s something that concerns you)?

It’s important to me that my work has these different layers of accessibility. My intention is to entice people to dig deeper into the questions I’m thinking about. But as long as some people go deep, I’m not worried when others don’t.

In fact, one of the reasons I often use humor as a strategic starting point is to encourage different types of uses for each work I make. This is because I not only enjoy the varied lives my projects live but also learn something new from each of them. As you might expect, sometimes it’s a user’s in-depth consideration that reveals new insights. But other times it’s the casual interaction that helps me better understand what I’ve made and how people think about my topic of interest.

Ultimately, in a world where so many of us engage with software all day long, I want us to think critically about what software is. How is it made? What does it do? Who does it serve? In other words, what are software’s cultural, social, and political effects? Because software is a layer of the world that is hard to see, I hope my work brings a bit more of it into focus for us all.

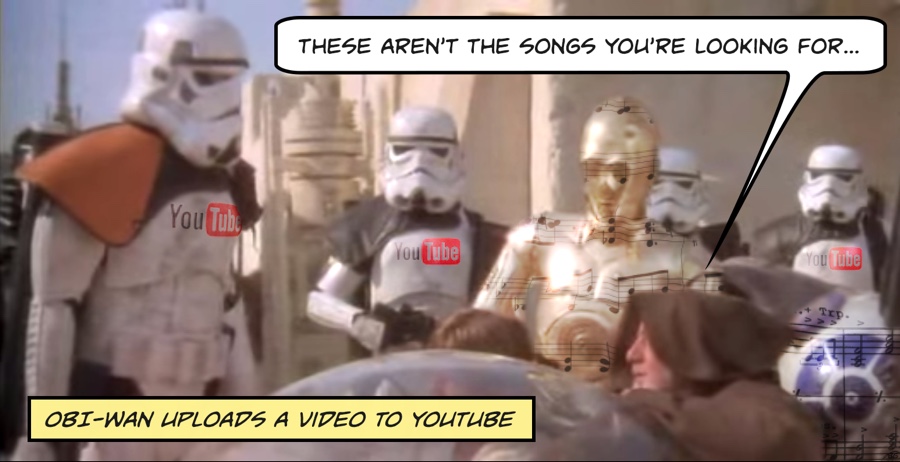

Ben Grosser, Music Obfuscator

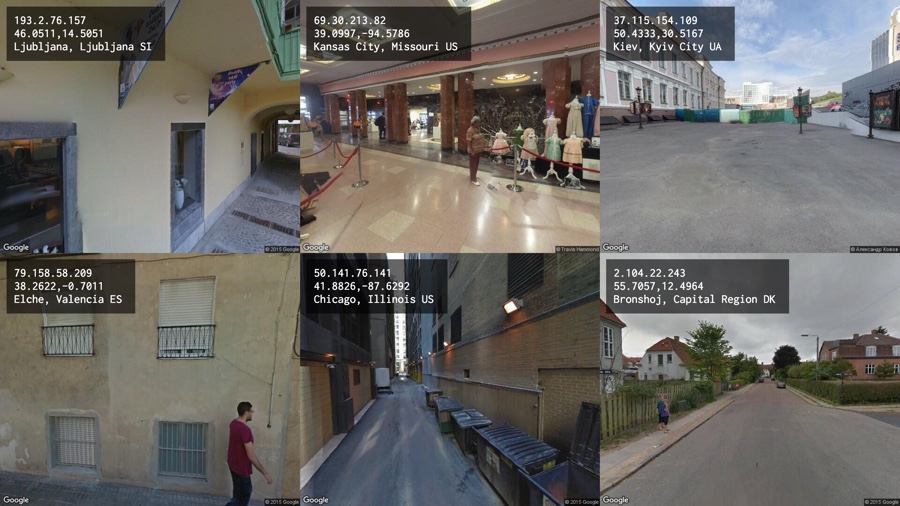

Ben Grosser, Tracing You (screenshot), 2015

Any upcoming work, field of research or events coming up after the exhibition at arebyte Gallery?

I have several works and papers in various stages of research or completion. I’ll mention three. Music Obfuscator is a web service that manipulates the signal of uploaded music tracks so that they can evade content identification algorithms on sites like YouTube and Vimeo. With this piece, I’m interested in the mechanisms and limits of computational listening. I have a lot done on this (I showed a preview at Piksel in Norway), but hope to finally release it to the public this spring or summer at the latest. I’m in the middle of research for a new robotics project called Autonomous Video Artist. This will be a self-propelled video capture robot that that seeks out, records, edits, and uploads its own video art to the web as a way of understanding how our own ways of seeing are culturally-developed. Finally, I have an article soon to be published in the journal Big Data & Society that will discuss reactions to my computational surveillance work Tracing You, illustrating how transparent surveillance reveals a desire for increased visibility online.

Thanks Ben!

Go Rando is part of Blinding Pleasures, a group show that explores the dangers and potentials of a conscious use of the mechanisms behind the False Consensus effect and its marketing-driven son, the so-called “Filter Bubble”. The show was curated by Filippo Lorenzin and is at arebyte Gallery in London until 18th March 2017.