Cellular agriculture, clean meat, cruelty-free, guilt-free meat! The promises and by-names of lab-grown meat might be seducing but they hide a series of unpalatable realities. The most contentious of all being its reliance on foetal bovine serum as a nutrient for the animal cells. Harvested from unborn calves, usually by drawing the blood directly from the heart of the foetus right after the pregnant mother has been slaughtered, FBS enables the cells to grow and multiply into meat for our consumption. There are plant-based alternatives to the FBS of course but their content and formulation is usually wrapped in IP claims, NDAs and secrecy. Lab-grown meat, this over-engineered response to the West’s addiction to animal flesh we’ve been reading about for years, is thus far less virtuous than it appears.

Theresa Schubert, mEat me, performance 06.02.2020. Photo: Tina Lagler / Kapelica Gallery Archive

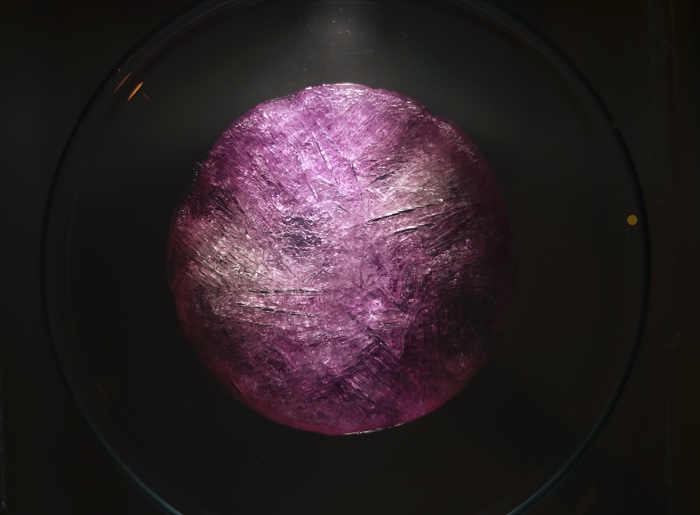

Theresa Schubert, mEat me, piece of the artist’s cultured muscle cells in a petri dish. Photo: Hana Josic / Kapelica Gallery Archive

Theresa Schubert confronted head on and with much pragmatism the dilemmas inherent to lab-grown meat by producing and eating her own meat. Literally.

mEAT me, a one year research collaboration between the artist, Kapelica Gallery in Ljubljana and bioengineers from Educell, saw Schubert produce meat grown from her own cells.

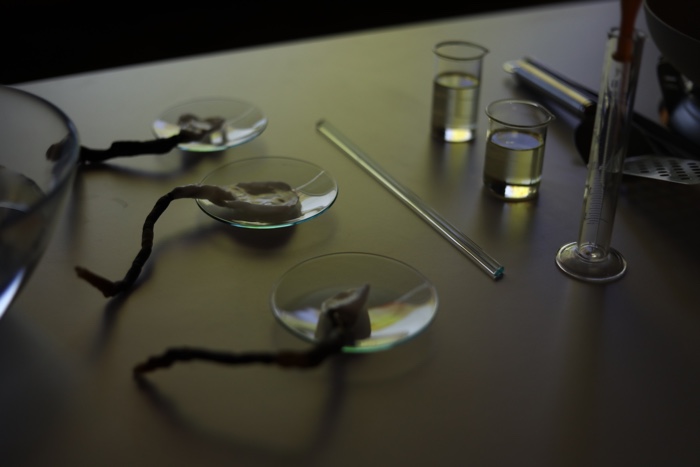

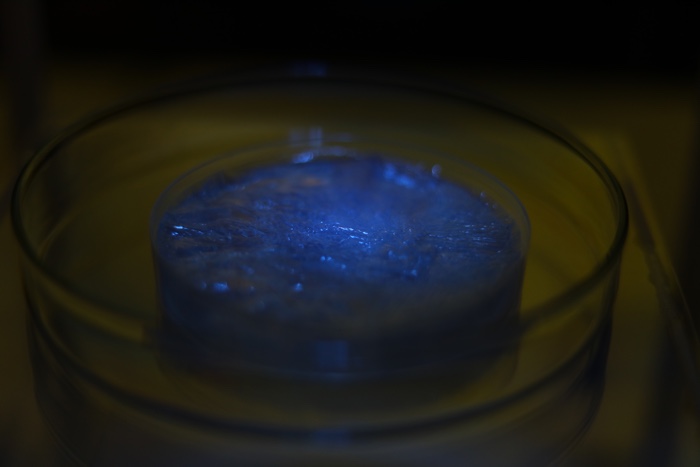

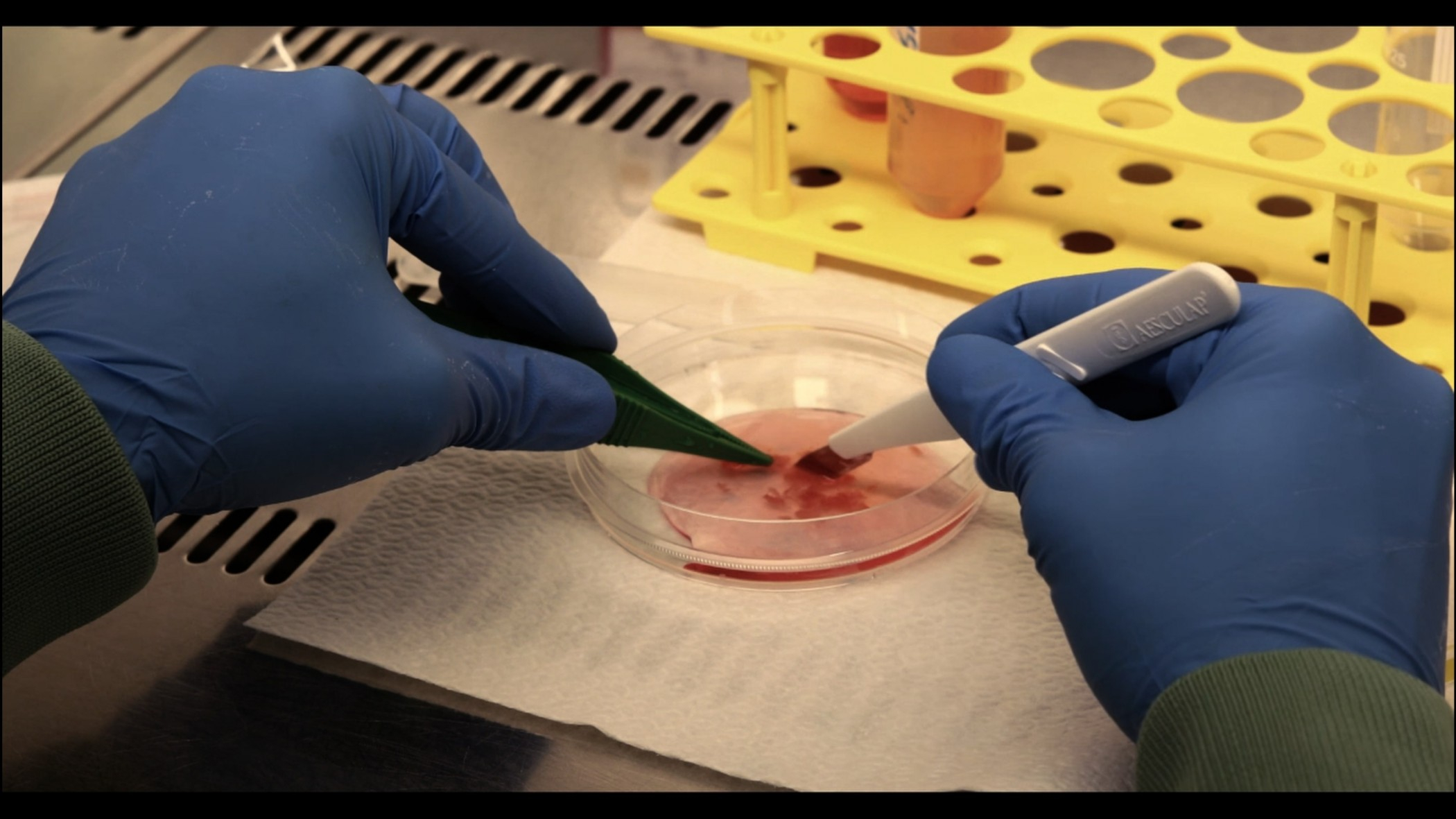

The artist multiplied cells from a biopsy of her thigh muscles in a serum made from her own blood. A few months later, the piece of in-vitro meat she had artificially grown exited the Educell laboratory to be eaten by the artist in front of the audience at Kapelica.

Theresa Schubert, mEat me, performance 06.02.2020. Photo: Tina Lagler / Kapelica Gallery Archive

Theresa Schubert, mEat me, performance 06.02.2020. Photo: Tina Lagler / Kapelica Gallery Archive

Theresa Schubert, mEat me, performance 06.02.2020. Photo: Tina Lagler / Kapelica Gallery Archive

During the first part of the performance, the artist sliced up a large piece of beef to recreate the biopsy during which a surgeon extracted cells from her leg. She then proceeded to prepare and eat the meat she had grown from her own flesh. The live event was accompanied by an installation, projections of audiovisual documentation of the laboratory process and the presentation of machine learning models that helped develop a complex narration around the topics of bioethics, animal rights and body politics.

In her project, Theresa Schubert views the human body as a food production unit, as an ever-renewing food source. By using new in vitro meat production techniques, we could use our own body to feed ourselves, we could literally eat ourselves and yet stay live. In the performance ‘mEat me’ the artistic gesture reaches into a hybrid space of alchemy, futuristic industry and posthumanism, and proposes a cannibalistic solution as a response to the ‘clean meat’ fake ethics.

I asked Theresa to tell us more about her work:

Theresa Schubert, mEat me, performance 06.02.2020. Photo: Tina Lagler / Kapelica Gallery Archive

Theresa Schubert, mEat me, performance 06.02.2020. Photo: Tina Lagler / Kapelica Gallery Archive

Theresa Schubert, mEat me, piece of the artist’s cultured meat after frying, 06.02.2020. Foto: Theresa Schubert

Hi Theresa! The presentation of the work mentions that one of the issues explored was “the understanding of the human as a product.” Could you elaborate on that? Where/when are we, as humans, treated as a product today?

With this statement, I wanted to contribute to the post-anthropocentric debate. Many thinkers of posthumanism stress a non-human-centred perspective on the world and that we should assume a more modest role in our dealings with nature, stop categorizing and that we as humans are likewise animals. Scrutinizing this idea of a ‘zoé-egalitarianism’, I wanted to treat the human as any other animal and hence as a source for potential food, because this is what animals are mostly for us.

I would like to take a step in another direction, looking at the ‘vitalist-mechanist controversy’ as Jane Bennett calls it. Descartes proclaimed that animals are non-sentient automatons, “they eat without pleasure, cry without pain… their screams are not more than the squeaking of a wheel”. His opinion was already by his coevals condemned as fatuous, murderous and monstrous; yet, looking at industrial farming and the current exploitation of animals for fashion and cosmetics, Descartes approach doesn’t the seem too far from our treatment of animals as machines reduced to producing organic material.

We are alienated these days from the production processes as they happen at places we usually don’t see. This disconnection allows to easily forgetting where for example the steak comes from. As long as mass production of meat is still being the predominant practice and reality of today, not eating meat is not only an ethical consequence but also a political statement. In my work, I wanted to draw attention to those bioethical issues and treat myself as a fleshy resource in a similar way.

The COVID-19 pandemic we are experiencing now has added another unforeseeable relevance to my project. A recent article has linked factory farming to the Corona virus. It explains how the animal industrialisation has required more and more space and in consequence, those farms were pushed out of inhabited zones, closer to the forest.

Currently the assumption is that the Corona virus may originate from bats, animals that are living in forests and thus get in contact with nearby farmed animals, which as intermediate hosts of the disease have infected humans through consumption. I really hope this might trigger a change in the food system, although I am doubtful. Let’s leave animals alone (better eat yourself).

Another aspect that may fit to your question of the human as a product goes into the practice of biotechnology. It is possible to grow new organs and tissue from our cells, genome editing in theory allows to construct a human as if it were an order for a product; this has turned our bodies into a ground for engineering, made it reconstructable to a certain degree. In conclusion, I am treating my body as a material – an impersonal, objective structure, an architecture in Stelarc’s words – to experiment with.

Theresa Schubert, mEat me, piece of the artist’s cultured muscle cells in a petri dish, 06.02.2020. Photo: Hana Josic / Kapelica Gallery Archive

Theresa Schubert, mEat me, performance 06.02.2020. Photo: Tina Lagler / Kapelica Gallery Archive

The serum you produced to feed the cells is extracted from your own blood. Is it as efficient and nutritious as the foetal calf one?

My scientific collaborator, Ariana Barlič, explained that foetal serum contains more bioactive molecules, which are required for foetus development. However, one can say FBS and human serum are similar, if it is only needed for cell proliferation and differentiation. It may grow slower, which was not a problem in my case.

Another background of the project originates from a criticism of established lab protocols and used media. The promise of a lab-grown meat as a more sustainable and cruelty-free alternative has been around for some years now. This sometimes-called ‘clean meat’ has had usually a big problem stemming from the origin of the culture medium. Most cell and tissue culture protocols are based on using FBS, foetal bovine serum, which might better be called lethal bovine serum, as the living cow foetus is drained from blood until death for its production. For these reasons, I wanted emphasize the use of animal free alternatives in the lab work. In addition, I wanted to elaborate on the idea of being able to feed yourself from within. To create a mechanism for self-sustainable nutrition, where the meat cells and nutritious medium comes from yourself – your body as an externalised production unit.

Theresa Schubert, mEat me. Handling biopsy cells in the laboratory

What are the technical and legal constraints of developing and then exhibiting a work like this? Does the fact that you are using your own cells attract more scrutiny and control than if you were using cells of any other animal?

I appreciate a lot having been able to work with Kapelica which has years of experience in developing challenging, thought-provoking projects that may be even disturbing to some people. In terms of my work, there was nothing illegal done. By German and Slovenian law – and I believe it’s similar in other countries – cannibalism per se is not a criminal offence. However, because it would involve either the killing or bodily harm of a person it is a criminal offence through that. Through implementing biotechnology, violence is removed from cannibalism, as no crime is involved in voluntary donation of cells and in vitro cultivation.

On another side, I had to do a screening for blood transferable diseases, such as Viruses. It would have been a risk to infect other people as I was offering my meat also to the audience. Even though it was cooked at high temperature, no expert we asked knew whether a contagion would be possible through mouth or stomach.

Concerning the question of having more control. Yes, it was the easiest to work with my own cells. Because I knew exactly what I was getting into. Aside from this convenience, the most important thing was that it was from the beginning of the project an integral part of the concept to work with my own cells. The project deals with topics that are very important to me. Undergoing the biopsy and see it grow in the lab added somewhat a more intimate connection to the cells that would not have been possible with cells of another person. I think also the pain I experienced after the biopsy, the fact that a real piece of me was missing, was essential in creating the dramaturgy of the performance.

Theresa Schubert, mEat me, audience post performance 06.02.2020. Photo: Tina Lagler / Kapelica Gallery Archive

Theresa Schubert, mEat me, audience post performance 06.02.2020. Photo: Tina Lagler / Kapelica Gallery Archive

The work confronts the taboo of eating human flesh. Not any human flesh but your own. From what I understood, the public reacted strongly to the work. Were they mostly shocked by the discovery of how the lab-grown meat is cultured (even though i’d expect the public of Kapelica to be fairly well informed on that issue), by the thought that we might swap lovely pigs and lambs with anything that’s lab-grown, or by the fact that you create food from your own flesh and then proceed to eat it?

Cannibalism is one of the big taboos that is still exists in our society. Mostly this topic is never discussed rationally but it is left for apocalyptic, dystopian scenarios in popular culture, series, films, music. Historically cannibalism was also used by the white western men to justify the killing of indigenous communities and conquer ‘new’ territories. Alleged cannibal communities on e.g. Caribbean islands were compared with as animals. A human that consumes another human loses its humanity and becomes animal, a beast. It would be another area to go into this but some of the historical discrepancy and contradiction was in the background informing my project.

The audience at Kapelica is one of the most open-minded you can get and also to some degree already accustomed to controversial projects that work with the body in extreme ways or use pioneering technologies. Foremost they were interested to understand whether this method of would be a technical option, viable to implement in reality. I don’t think lab-grown meat of whatever origin is a shock, it’s just more or less accepted depending on the cultural connotation in your country and how accepted biotechnological practices are. More of a provocation was obviously to eat myself and share it.

Theresa Schubert, mEat me, performance 06.02.2020. Photo: Tina Lagler / Kapelica Gallery Archive

I have to ask you the obvious question: what does it feel to eat your own flesh?

And are you a vegetarian or vegan? Because in that case your answer might take a different dimension…

Exciting.

Incomparable.

And anxious as it happened in front of an audience. Actually, I am still reflecting on this. At that moment, I was so concentrated and nearly in another state of mind, that it seems to be an unconscious memory, like a dream, where you are not completely aware of your doings.

The taste was artificial and sleek, unlike any other — nearly a bit boring as I opted for the absolute natural taste without adding any spices or other ingredients.

I am vegetarian but not vegan. I was very curious but still had to overcome myself to do the first bite and swallow. I am not sure but somehow I had already a feeling of disassociation between my real self and what was in the petri dish. It did not look anymore like the cut out piece from my leg. It was merged with an edible scaffold looking like a thin semi-transparent burger patty and not having the proper meaty structure, as there was no blood vessels or fat tissue.

Theresa Schubert, mEat me (5.1) – excerpt from stage video of performance, 2020

Could you tell us something about the artificial persona for the lab-grown cells you created? How does it work and what kind of persona is it?

For the performance, I took on the role of several personas. In the first part, I was taking on the role of a butcher cutting up meat. The third part of the performance was me preparing, cooking, tasting and sharing the meat.

The second part was a staged dialog between my artificial self and me. In advance, I used a machine-learning algorithm based on a GPT-2 model that I fed with my conceptual texts. The model generated text responses that were based on a search through the Internet. The algorithms looks through websites, blogs, forums and synthesizes a new text that per se has not been written before but is based on whatever has been published online. One could say that these texts represent the voice of the Internet as an AI interprets it based on my specific input. From the text results, my sound collaborator Moisés Horta created a voice clone of myself. He trained a neural network with a prior recording of me reading a text so it would learn my timbre and intonation. This model was then used to vocalise the generated GPT-2 text. In the performance, I staged myself in a dialog with my voice clone in combination with a projection screening videos from the laboratory process and the texts. I was speaking into a microphone and the artificial me was speaking back to me with my cloned voice somewhat giving a personality to my cultivated cells.

What are you working on at the moment? Any new areas of research or specific project coming up?

Currently I am developing a new piece that is based on my residency within “Mind the Fungi”, a 2 year-long interdisciplinary research project between Technical University Berlin and ArtLaboratory Berlin. The residency took place at the group of General and Molecular Microbiology (AMM). I was doing a series of experiments investigating the influence of sound frequencies on the morphology and metabolism of local arboreal fungi mycelium and now I am translating this into an interactive, sensorial work for an exhibition.

Further, last year I did a residency at the Poznan Supercomputing and Networking Centre in Poland and I produced a lot of video material in advance for a film that I keep working on now whenever I have free time. We did 3D laser scans in forests and inside their server room, as well as some 8K filming. The film is reflecting about the connections between a technologized city and the outside nature exploring themes of (non-)human life, machine intentionality and future societal structures.

I got very enthusiastic about laser scanning, as it is a different approach to capture a scene. The scans create large point clouds and the points can be overlaid with real photo images; transferred into the computer you can create virtual camera movements around the landscapes. So this is a technology that I want to explore more in my art practice.

Thanks Theresa!

Stories for vegan and carnists: Vapour Meat: a helmet to vape the essence of ‘clean meat’, The Meat Licence Proposal, interview with John O’Shea, From knitted meat to obsolete supermarket. Rethinking our food system, Can blood ever be a material like any other?, “Dangerous Art”: the latest issue of the (free) Experimental Emerging Art Magazine, etc.