16 years after its first edition, the Interferenze Festival was back in San Martino Valle Caudina to address technological culture and sound art in rural contexts. The festival deploys art and technology to show all the nuances of rural areas, demonstrating that rurality is a concept at the crossroad of geography, history and sociology. Any conversation around it should thus go beyond the usual clichés and binaries such as urban vs rural or traditional vs innovative.

Interferenze 2022. Photo: Fabio Perletta

Interferenze 2022. Photo: Leandro Pisano

The setting of the festival is rather lovely. San Martino Valle Caudina is a small town of fewer than 5000 inhabitants. It is an hour drive from Naples and several scenes from one of my favourite films, L’uomo in più by Paolo Sorrentino and with the sublime Toni Servillo, were shot there. The place comes with all the trappings of an Italian town: medieval fortress, fancy castle, various religious buildings and people sitting outside in the shadow. The festival was spread throughout the town. At the Gardens of Palazzo Ducale, the Gardens of Casa Giulia, at the local headquarters of the Sinistra Italiana (the left-wing party), in an ex-windmill and of course on the main town square.

It’s only the second time I attend an edition of Interferenze. Each time, the event feels like an enchanting parenthesis in the brutal Summer months. The programme was particularly exciting this year. There were performances, DJ sets, installations, screenings, etc. The talks were particularly good: dense, enlightening and covering ideas I wasn’t so familiar with. This post is going to cover the conference part:

Elena Biserna, Raquel Castro and moderator Francesco Bergamo. Photo: Leandro Pisano

Elena Biserna and Raquel Castro shared a panel focusing on the critical practices and theories they have developed around sound.

Raquel Castro, filmmaker, founder and creator of Lisboa Soa talked about acoustic ecology and why public space is an ideal arena where citizens can question democratic processes and use sounds to protest. I’ve briefly presented her work at Lisboa Soa a couple of weeks ago so I’ll jump right to Elena Biserna‘s contribution to the panel.

Biserna is a researcher, art historian, activist and curator. In her fascinating talk, titled “Soundwalking as a feminist”, she questioned the traditional literature around walking. From Charles Baudelaire, to Benjamin and other adepts of the flâneur practice, artists and thinkers have considered walking as a way to establish a relation with space, a way to observe, understand and read space from an inner perspective. It is a tactic of reappropriation of the urban system, an emancipatory practice, an exercise of citizenship. At some point, however, Biserna started to wonder whether all these potentialities offered by walking were really accessible everywhere and for everyone.

Who has the ability to practice dérive in a visible way? Who feels entitled to practice sound walk or even be visible and audible in public space? Is this narrative of the walker universal? Who has the freedom to practice flânerie, dérive or sound walks?

The public space is still characterised by deep asymmetries and violent forms of oppression. Not all bodies have the right to access any place and claim it as theirs. In the 1950s, the anthropologist Marcel Mauss was already highlighting the role that culture and society play in determining how we walk. Decades later, feminist, decolonial, anti racist critique and critical disability studies have started to deconstruct this essentialisation of walking and stressed the importance of what Donna Haraway calls situated knowledge. They showed that this universalism dissimulates a specific position, the position of the dominant which is made possible by practices and institutions that legitimise its supposed neutrality.

The flaneur as it has originally been described feels at home everywhere and enjoys the pleasure of observing. Women and other marginalised bodies do not have that privilege: they fear being visible or audible in certain spaces and at certain times (often during the night.) When we talk about sound walking we need to acknowledge its different realities.

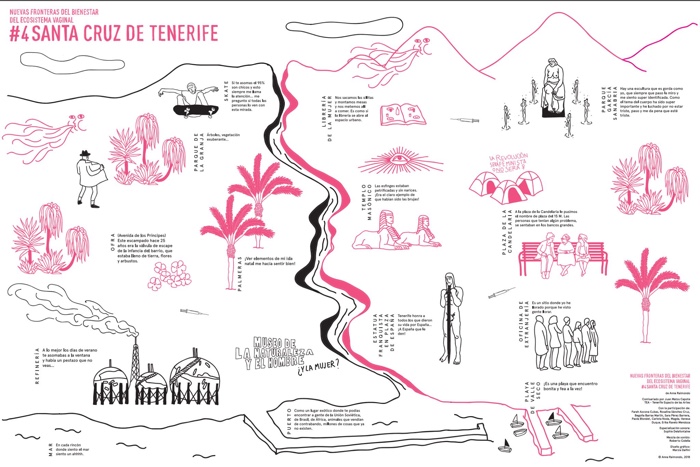

Anna Raimondo, New boundaries of the well-being of vaginal ecosystem #4 S.Cruz de Tenerife, 2018

Alisa Oleva, Walking home, still from the film

Amanda Gutiérrez, Flâneuse>La caminanta teaser

Speaking from her own position as a white European woman, Biserna briefly pointed us to artistic projects that account for different experiences of listening in public space, challenge the universal vision of the walking body and become world-making.

The Step By Step Guide To Unapologetic Walking is helping Indian women unlearn the way they should walk and by that deconstruct the patriarchal space.

First called “New boundaries of the well-being of vaginal ecosystem” then Q(ee)R Codes, Anna Raimondo‘s series of participatory and psychogeographical maps of Rome, Valparaiso, Tenerife and Brussels evokes the experience of cis, trans and queer women in urban space.

Flâneuse La Caminanta, by Amanda Gutiérrez, is a VR installation that documents soundwalks of female participants as they navigate urban landscapes in Mexico City, Abu Dhabi and New York.

Walking Home connects Alisa Oleva with women from Istanbul. While the participant was walking towards the place which she describes as “home” in Istanbul, the artist walked with her in her own city, sharing footsteps and a discussion over the phone about where it feels like home for them.

Based on awareness, solidarity and possible alliances, these works build a collective political subjectivity and challenge the idea of a neutral soundscape.

Elena Biserna has just published Walking from Scores and I’m looking forward to reading it.

Yanni Lolis from Medea Electronique, Alessandro Ludovico from the University of Southampton, artist and curator Maite Cajaraville, Yukiko Shikata, EIR – Energies in the Rural and me! Photo: Francesco Bergamo

The panel titled Electronic Art Rural Forum kickstarted the process of developing a network of independent organisations that work with art and techno-cultures in rural contexts. Actors working in Spain, Greece, Japan and Italy discussed how technologies can be used by artists as critical devices of territorial inquiry but also as tools to develop counter-narratives related to rurality representation.

Maite Cajaraville, VEXTRE (detail of the sculpture.) Image via rtve

Maite Cajaraville, VEXTRE. Augmented reality app

The first contributor was Maite Cajaraville. She is an artist, curator and cultural manager. Originally from Extremadura, Cajaraville describes the region as a very rural and poor area no one really cares about it. Except to exploit its resources. Extremadura has so far mostly been seen merely as a source of agricultural profits. Recently, more opportunities for “extractivism” have arisen: the project of opening one of Europe’s largest lithium mines, plans for macro photovoltaic plants, mega structures for extensive pig farming, etc. These lucrative projects will have heavy costs in terms of the preservation of cultural heritage and the environment. Furthermore, people living in Extremadura almost never get anything in return as most of these projects -from the Pata Negra industry to mineral mining- are managed by companies located in other regions in Spain or elsewhere. As a result, people have an image of Extremadura that is deeply rooted in stereotypes of socio-economic underdevelopment.

The artist developed a 3D augmented reality model that visualises economic and social data in Extremadura. Called VEXTRE, the work looks at trends (or abnormalities) in population and depopulation, economic growth and decline, local and international trades, etc.

The artist later developed a similar map for the region of Alentejo in Portugal. Because it shows roughly similar patterns than the ones revealed by the VEXTRE project, ALVEX suggests that the problems faced by rural areas in Spain can be found elsewhere in Europe. She calls this phenomenon Europa vaciada (Emptied Europe) in reference to the expression España Vaciada. There are certainly similar concerns about the emptying of rural areas in France, Italy, Germany, etc.

VEXTRE taps into these anxieties by trying to raise debates among people who live in Extremadura, inviting them to explore the map in order to better understand their territory, have them compare the fate of their home town with others in the region, generate narratives that go beyond the usual clichés and ultimately get involved in debates about the challenges their area is facing.

Agia Kyriaki (translated: The Kyriaki monastery), Koumaria Residency 2015

Medea Electronique, Koumaria Residency. Photo

Medea Electronique, Koumaria Residency. Photo: Interface Medea

The next speaker in the panel was Yannis Lolis, a video artist and graphic designer from Athens. Lolis is a member of Medea Electronique, a collective of creative people active in all disciplines and interested in innovation and contemporary art. Since 2009, Medea Electronique organises a residency called Koumaria. Located in an olive oil farm on the outskirts of a small village of 300 people, a 20-minute car ride from Sparta, the residency hosts new media artists from around the world for the creation of collective cross-arts projects grounded in an improvisatory philosophy. For 10 days, 16 people work -on films, staged shows, animated shorts, eat together every night at 8 pm the food they have cooked at the residency and stage after dinner improv sessions.

Over time, they started showing the results of the residencies in the village and gathering narratives from the villagers which opened up different relationships with the local community.

Soichiro Mihara, EIR – Energies in the Rural. Photo: Fabio Perletta

Soichiro Mihara, EIR – Energies in the Rural. Photo: Fabio Perletta

Soichiro Mihara, EIR – Energies in the Rural. Photo: Leandro Pisano

Soichiro Mihara, EIR – Energies in the Rural. Photo: Leandro Pisano

Soichiro Mihara, EIR – Energies in the Rural. Photo: Fabio Perletta

Soichiro Mihara in Pollinaria. Photo: Pollinaria, via ACAC

Soichiro Mihara in Pollinaria. Photo: Sabrina Caramico

Yukiko Shikata, a curator, visiting professor and art critic based in Tokyo presented EIR – Energies in the Rural. The project uses technological art to investigate the invisible forces that contribute to transforming ecosystems and communities: earth sounds, earth signals, human and non-human corporeal energies. EIR is anchored in two rural areas that, even though they are very distant from each other, are going through a process of territorial transformation. One is located in the region of Aomori (Japan) and is anchored at the Aomori Contemporary Art Centre, a cultural centre isolated from residential areas. The other covers three locations in Southern Italy: Pollinaria in Abruzzo, the Ethnographic Museum “Beniamino Tartaglia” in Alta Irpinia and the festival Interferenze / Liminaria in San Martino Valle Caudina. In another session, Yukiko Shikata invited media artist Soichiro Mihara to present to the public the result of his EIR residence in Italy where he participated in the harvest of wheat, made tomato sauce and pursued his interest in smell related with wind or flow of air.

The performance was rather brilliant: he captured the “air of the day” using plants he collected, a transparent balloon and pages of a daily newspaper he had just bought.

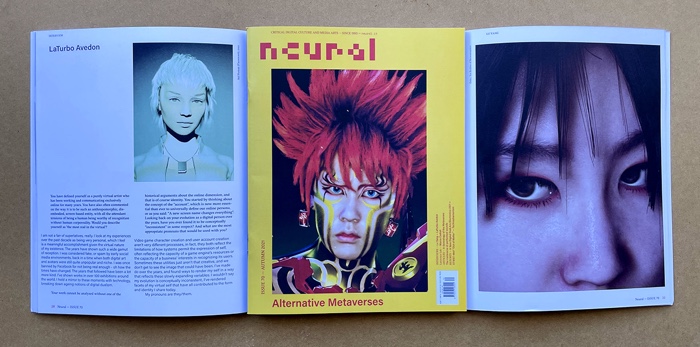

NEURAL 70, Alternative Metaverses

Alessandro Ludovico, a researcher, artist, author, the chief editor of Neural magazine since 1993 and an Associate Professor at the Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton.

Ludovico closed the panel by highlighting a couple of characteristics important in the context of art and tech, especially when applied to rural areas. Small places, he said, have a different experience of time and space compared to urban areas. People enjoy more space while maintaining closer relationships with each other. Another important element is the powerful small computers we carry around. They are part of an infrastructure and network whose functioning is dictated by the industry. And its dynamics are miles away from the utopia of the early days of the Internet. Ludovico believes that rural communities can play a crucial role in (finally) establishing horizontal, critical and free communication among people. This new paradigm would help strengthen the connections and synergies between rural places around the world where artists and cultural actors operate.

I’m going to end this report with a few words about one of the installations I saw at Interferenze.

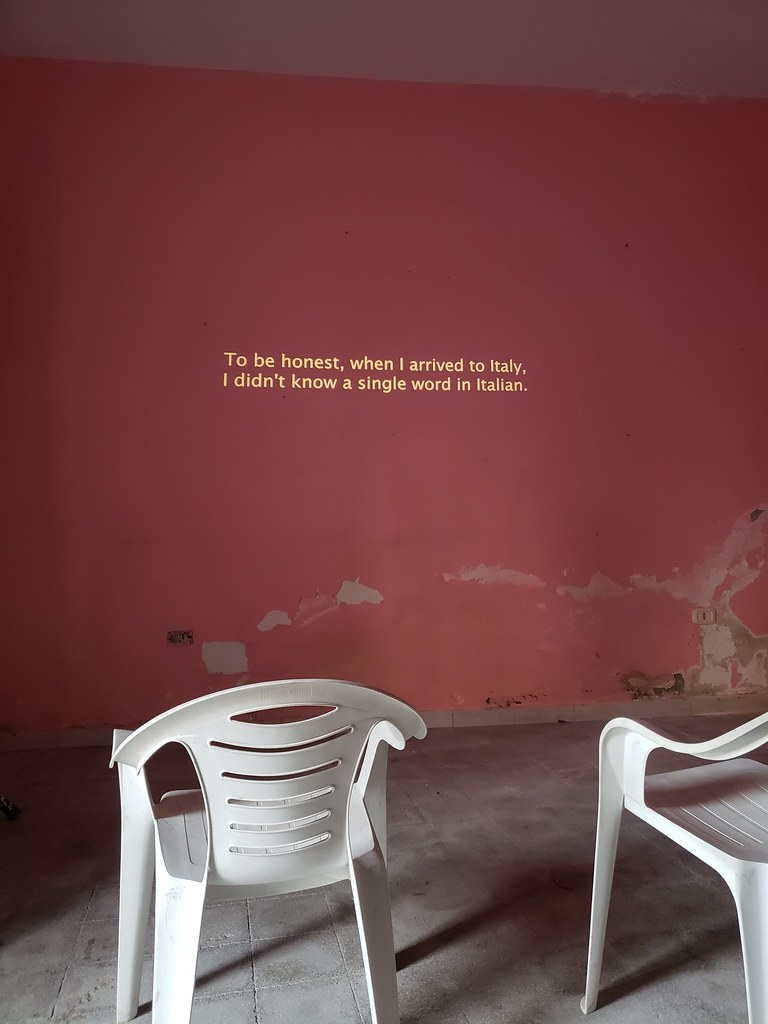

Iana Stefanova, Ellipses, 2022 Interferenze 2022

Iana Stefanova’s Ellipses is an audiovisual work that lasts 56 minutes. It has no images. Just subtitles and voices that alternate between Italian, Russian, Ukrainian and English. You can’t imagine a more stripped-back production and yet I found it incredibly moving.

The voices you hear belong to the so-called “badanti”, the migrant caregivers who come mainly from Eastern Europe and move to Italy to provide services for people with care needs, enabling families to keep their elderly parents living comfortably in their own home for as long as possible. The women also play a vital role in filling the gaps in the Italian health and social system.

In Italy, we all know about the existence of the badanti and we know what they do but that’s about it. Mainstream Italian media either ignore these women or run sensational stories about how much they are exploited.

Between 2017 and 2019, Iana Stefanova met some of these workers in various cities in the Campania region. I don’t know what magical recipe the artist used but she managed to get extraordinary stories from these women. They narrate their daily life, how they arrived in Italy and how lonely they often feel. They spend most of their days providing “continuous” care and are far away from their families. Sometimes, they even move from one Italian city to another when they need to find another person to assist. There is also a lot that you can guess through the silence, hesitations and hints.

The women didn’t want to be video recorded. Hence the minimalist approach. And it works. You don’t need to see the face of these women to be gripped by their stories, humour, strengths and emotions.

More images from the festival:

Populous at Interferenze 2022. Photo: Leandro Pisano

Go Dugong at Interferenze 2022. Photo: Leandro Pisano

Workshop: Soil as Experience, by artists Andrea Caretto & Raffaella Spagna and by curator Alessandra Pioselli. Photo: Leandro Pisano

Presentation of the workshop: Soil as Experience, by artists Andrea Caretto & Raffaella Spagna and by curator Alessandra Pioselli. Photo: Leandro Pisano

Interferenze 2022. Photo: Leandro Pisano

Previously: Sound art, Ecology and Auditory culture. Lisboa Soa 2016-2020; The Manifesto of Rural Futurism; The Sounds of Absence and narco-violence.