How To Live Together, an exhibition currently on view at Kunsthalle Wien, aims to looks that the conditions and prospects of living together in terms of individual and social dimensions.

Installation view: How To Live Together, Kunsthalle Wien 2017, Photo: Stephan Wyckoff: Goshka Macuga, To the Son of Man Who Ate the Scroll, 2016

Paul Graham, Beyond Caring, 1984/8

This is a brave, laudable and rather ambitious objective at a time characterized by tightening borders, stigmatizing discourses, political debates inside filter bubbles, and other suggestions that the world is not only melting under our feet but also intent on cultivating divisions.

The exhibition is located over two floors. It is huge and it can feel as overwhelming as the theme it purports to explore: Tina Barney’s photos of the European one per cent are hung in uncomfortable proximity of the ones Mohamed Bourouissa made of the deserted youth in the Paris suburbs; Jeroen de Rijke and Willem de Rooij‘s videos of drug addicts trying to stare at the camera in exchange for a beer make for an almost unbearable watch and Paul Graham‘s photos of everyday life at the (un)employment offices in the 1980s are too close to home 30 years later.

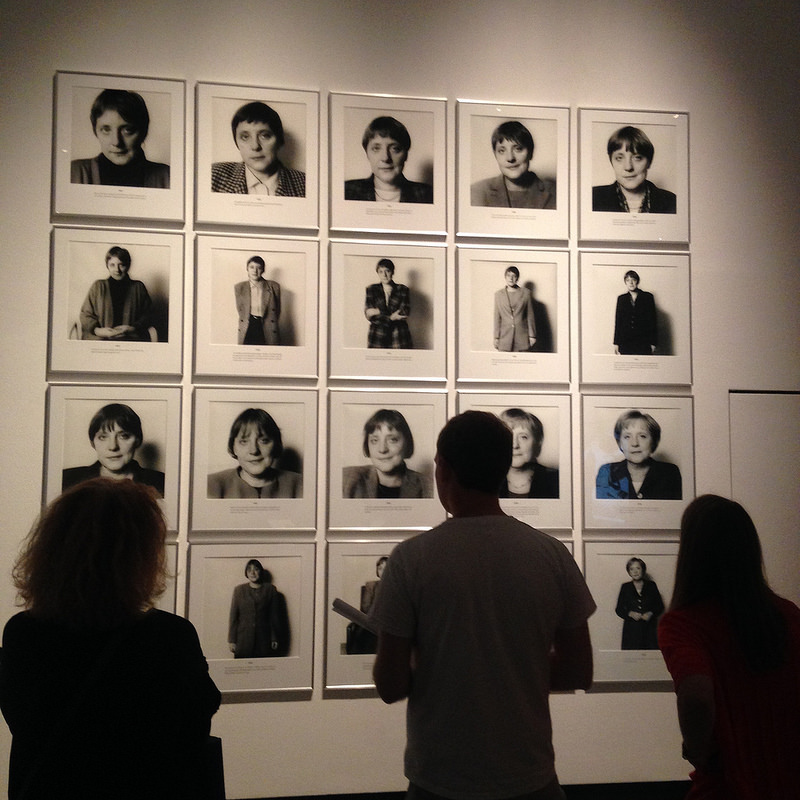

Fortunately, the curators of How To Live Together didn’t just summon grim visions, they also searched for glimpses of hope, signs of change, and lessons from other cultures. Wolfgang Tillmans’ poignant Anti-Brexit campaign reminds us why artists need to take an active role in civil society; Ayzit Bostan‘s Imagine Peace written in arabic on t-shirts challenges society’s prejudices; Johan Grimonprez‘s Kiss-o-drome illustrates how humour and love can challenge censorship. Speaking of humour… the main image of the exhibition with its Merkel diamond gesture is an amusing echo to Herlinde Koelbl‘s portraits of Angela Merkel over decades. Those portraits were probably the most scrutinised works in the whole Kunsthalle, by the way.

Herlinde Koelbl, Angela Merkel, 1991–2006, from the cycle: Spuren der Macht (Traces of Power) at Kunsthalle Wien

Because it’s almost 40 degrees this week in Turin and i’m in a murderous mood, i’m going to split my review of the show into two parts. Today, you get the depressing bits and as soon as temperatures have cooled off a little, i’ll be back with the works that speak of solidarity, optimism and compassion.

It’s not all bad though because 1. i loved that show so much i visited it twice and 2. i’m going to open the quick gallery tour with one of my favourite artists:

Mohamed Bourouissa, Carré rouge (from the series Périphérique), 2005

Mohamed Bourouissa, La République (from the series Périphérique), 2005

Mohamed Bourouissa, Le miroir (from the series Périphérique), 2005

Installation view: How To Live Together, Kunsthalle Wien 2017, Photo: Jorit Aust

“I wanted to represent the guys from the banlieues, who are generally only portrayed by news reporters, and to lift this type of imagery into the field of aesthetics,” explained Mohamed Bourouissa in an interview with Elephant.

Made in 2005, in the context of the riots in the French banlieues, the series has as its main protagonists the young Africans and Arabs living in the suburbs of Paris.

Because we are used to seeing them portrayed by news reporters, most of us would probably take our cue from their outfits and surrounding and automatically assume that we are looking at scenes of trouble. But Bourouissa’s photos are carefully staged and lit as if they were tableaux vivants. The subtle aesthetics strategy challenges our own prejudices as well as the over-simplification of photojournalism that often fails to convey more complex socio-political contexts. His photos also seems to invite us to face uncomfortable issues head on.

Mohamed Bourouissa, L’Utopie d’August Sander, 2012–2013

Installation view: How To Live Together, Kunsthalle Wien 2017, Photo: Jorit Aust. Mohamed Bourouissa, L’Utopie d’August Sander, 2012–2013

L’Utopie d’August Sander, another Bourouissa work in the show, refers to August Sander‘s magnum opus Menschen des 20. Jahrhunderts (People of the 20th Century, also on view at Kunsthalle Wien.) This photographic atlas was intended to be a “contemporary portrait of the German man”.

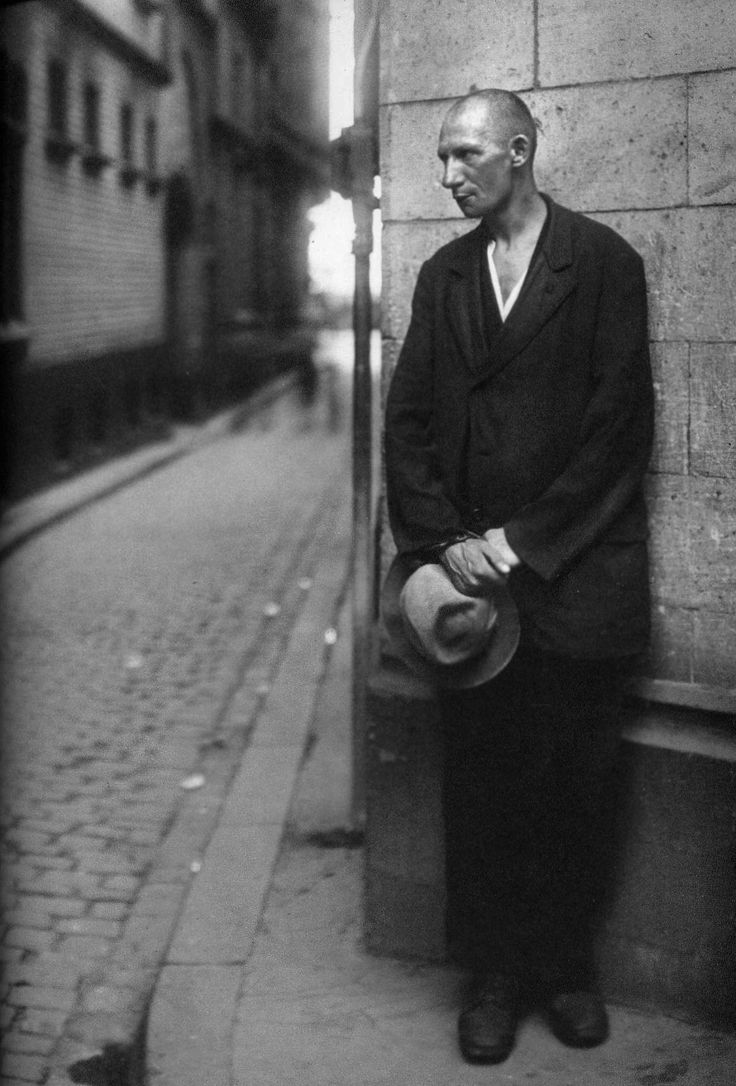

August Sander, Jobless, 1928/1993

Sander’s portraits were grouped into seven portfolios, each dedicated to a specific social and occupational group. He portrayed craftsmen, industrialists, farmers but also elements of German society that were regarded as less ‘respectable’: traveling people, beggars, the disabled, the unemployed. Their inclusion in the work is probably what raised the ire of the Nazi who, in 1936, confiscated the first published version of the project and destroyed all the printing plates.

Bourouissa’s work limits his portrayal of society to the unemployed but he anchors it into the 21st century by using 3D printing. His studio was located inside a “fab-lab mobile”. He parked his truck outside a Pôle emploi (French national unemployment agency) in Marseille and asked people in search of work if he could 3D scan them and turn them into figurines, which some likened to the santon tradition in the South East of France.

By being at the crossroads of integration and social exclusion, unemployment offices remind us how much we are defined by our social status. The polyester resin statuettes are anti-monuments to this uneasy position. The figurines respect the anonymity of the job-seeker but because they are different from each other, they also mirror the singular identities of the people who aspire to play the role that modern society expects from them.

Mohamed Bourouissa, L’Utopie d’August Sander, 2012. Image via exponaute

As a nod to the economy of precariousness and resourcefulness that surrounds unemployment, Bourouissa sold the statuettes on the street for 1 Euro.

For the artist, the work process was far more important than the statuettes. His documentation of the work includes a ‘livre des refus’ (book of refusals) in which he chronicles the reactions of people who said ‘no’ to his requests and accused him of using his artistic privileges to exploit people.

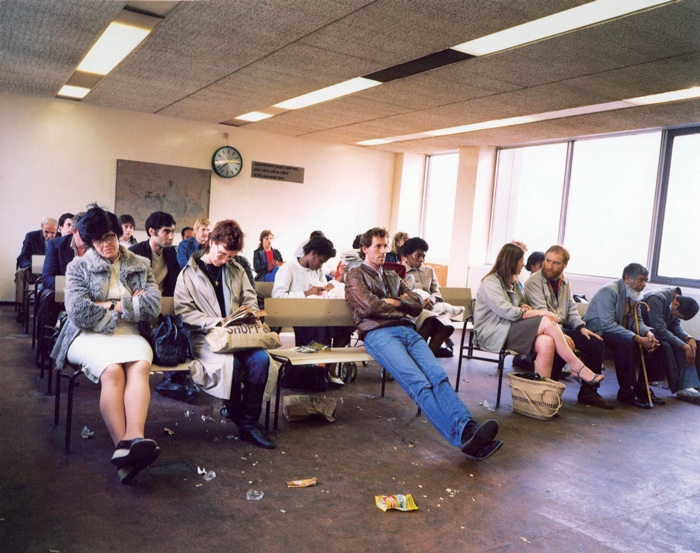

Paul Graham, Beyond Caring, 1984/8

Paul Graham, Beyond Caring (Waiting room, Highgate DHSS, North London), 1984/8

Installation view: How To Live Together, Kunsthalle Wien 2017, Photo: Jorit Aust. Paul Graham, Beyond Caring, 1984/8

In 1984, Paul Graham was commissioned to present his view of “Britain in 1984”. He chose to document the inside of English unemployment offices which, at the time, struggled to accommodate the 3 million people who found themselves out of work. Graham wasn’t allowed to take these images, meaning that he had to hide his camera under his coat or put it on the chair beside him. He thus had to shoot instinctively, often unable to look through the viewfinder. Yet, the images seem imbued with empathy.

The images of people sitting dejectedly in run-down waiting rooms under hostile neon lights attest to the breakdown of the welfare benefits system across the country. The series also holds a bitter mirror to contemporary economic systems that cultivate social inequality and political discourses that blame the poor for their own circumstances.

Over time the work acquired “this strange double life: as both a political work of social reportage handed out at lefty political conferences, and as a fine art photography book”.

Aslan Gaisumov, stills from the video People of No Consequence, Chechnya, 2016

Aslan Gaisumov, stills from the video People of No Consequence, Chechnya, 2016

Aslan Gaisumov, Production photo for People of No Consequence, 2016

From 23 February to 9 March 1944 the entire Chechen and Ingush nations, about half a million people, were deported to Central Asia by the Soviet authorities. They had been declared guilty of cooperation with Nazi occupants. Almost half of all Chechens died or were killed during the round-ups and transportation, and during their early years in exile.

The expulsion was part of a forced settlement program and population transfer that affected several million members of non-Russian Soviet ethnic minorities between the 1930s and the 1950s.

Survivors were allowed to return to their native land only in 1957. Many in Chechnya and Ingushetia classify it as an act of genocide, as did the European Parliament in 2004.

Aslan Gaisumov traveled across Chechnya searching for survivors of the deportation. He managed to gather 119 of them in Grozny. 60 years after they had lost their home. People of No Consequence is a quiet, hypnotizing single shot of these people entering an official looking room and sitting down facing the camera. First, the men. Then the women who go and sit at the back. On the wall at the back of the room, a poster depicts Grozny as a city that has erased all traces of recent wars in favour of pompous, alienating architecture. People of No Consequence is an incredibly moving work. The frail people in the film are the last witnesses of an injustice that hasn’t been given a place in official historical accounts.

Aslan Gaisumov had two video pieces in the shows. Both amazing in strength and simplicity. He approaches the darkest and understudied pages in the history of his country without sensationalism, bitterness nor unnecessary pathos.

Installation view: How To Live Together, Kunsthalle Wien 2017, Photo: Jorit Aust. Sven Augustijnen, Le Réduit, 2016

Sven Augustijnen, Le Réduit, 2016

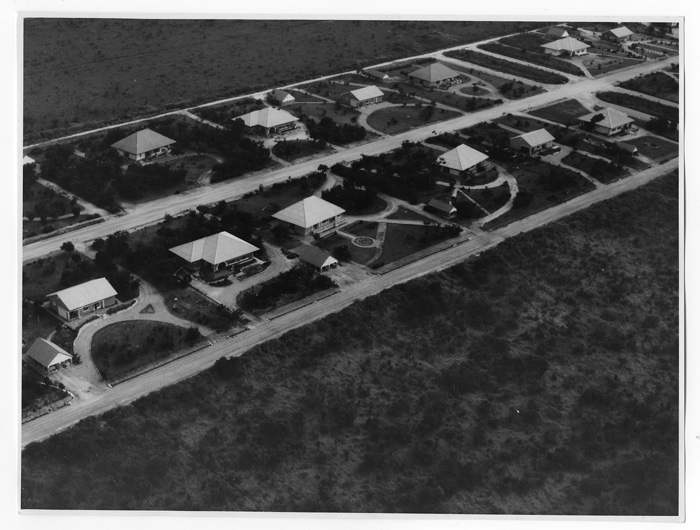

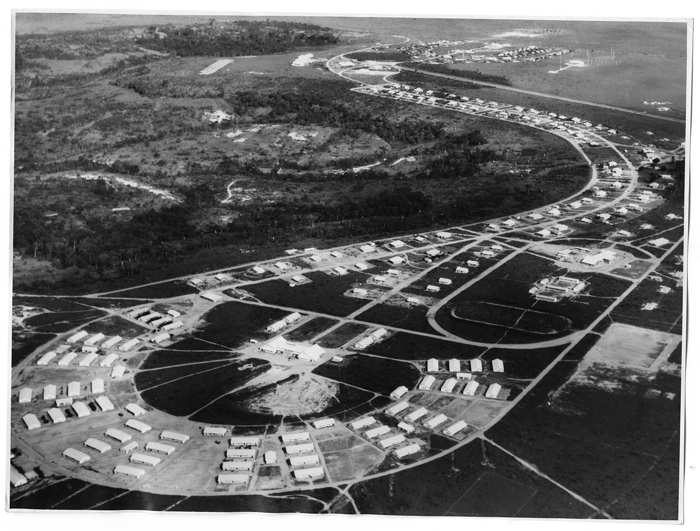

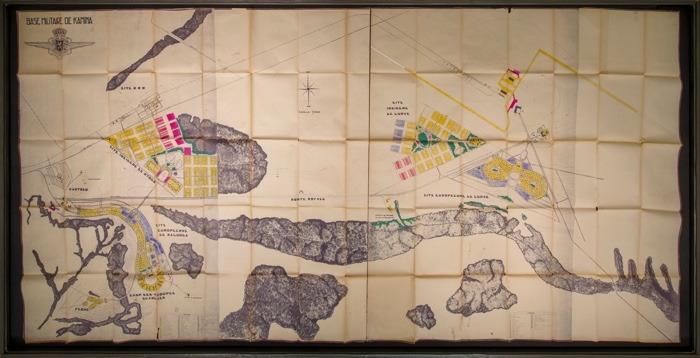

Sven Augustijnen, Le Réduit (Aerial views of Kamina Base), 2016

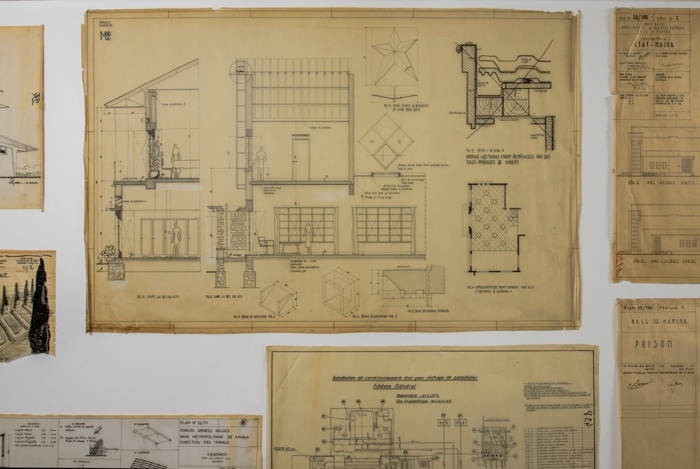

Sven Augustijnen, Le Réduit, 2016

Sven Augustijnen, Le Réduit, 2016

Now for a bit of that famous Belgian surrealism:

While doing some research about Belgium’s colonial history in the Congo (now DRC), Sven Augustijnen found out that, during the 1950s, his country had planned to build a huge refuge for the Belgian elite in Kamina, located in the rich mining region of Katanga in what was then the Belgian Congo.

Augustijnen analysed the thousands of photos, negatives, carbon copies, maps and architectural plans he had discovered at Belgium’s Centre de Documentation historique des Forces armées. They had never been studied before.

The documents show that the Belgian government had planned to create a huge military base and a haven for the royal family and their entourage. The exclusive hideaway would have served as a second Belgian capital and refuge in case of a communist invasion in Europe. Which is pretty ironic when you think that many of these people were happy to exploit the African territory from a distance but had probably never set a foot on it.

Using the archival materials as well as a short trip he made to Kamina last year, the artist wrote a story that balances historical facts and fiction to explain the Belgian government’s absurd and ambitious secret plan.

Installation view: How To Live Together, Kunsthalle Wien 2017, Photo: Jorit Aust. Jeremy Shaw, Quickeners, 2014

That’s it for today! I’ll see you at the other end of the heat wave!

Installation view: How To Live Together, Kunsthalle Wien 2017, Photo: Jorit Aust

If you want to know more about the show, have a look at HTLT’s playlist or download the PDF of the exhibition booklet.

How To Live Together is at Kunsthalle Wien until 15 October 2017. The show was curated by Nicolaus Schafhausen, with curatorial assistant Juliane Bischoff

Also on view at Kunsthalle Wien (Karlsplatz location): Work it, Feel it! New mechanisms of body discipline.