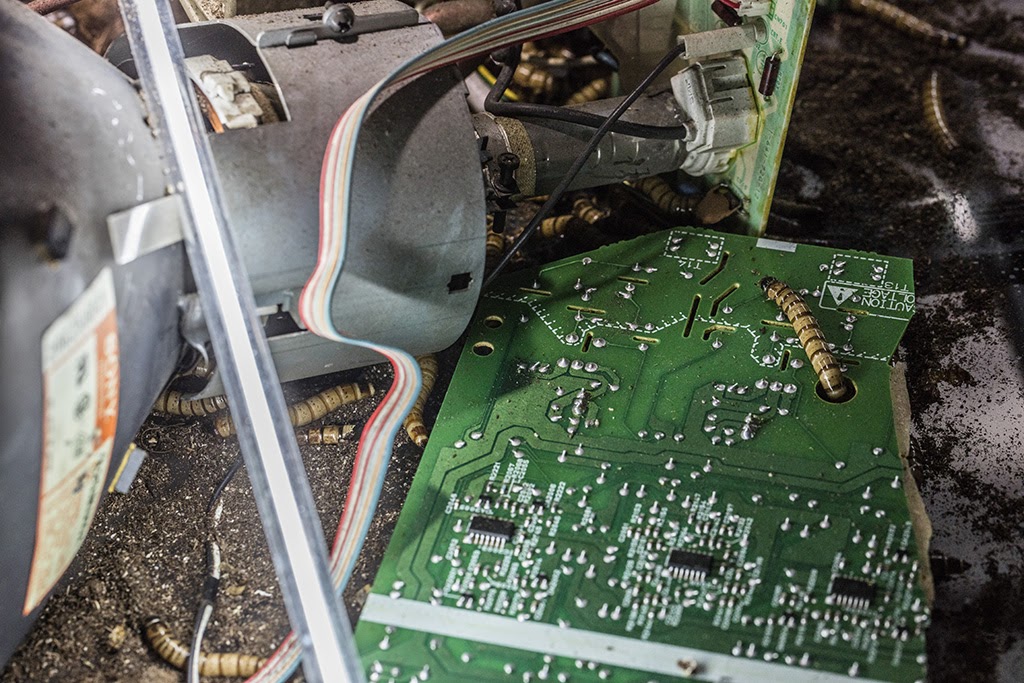

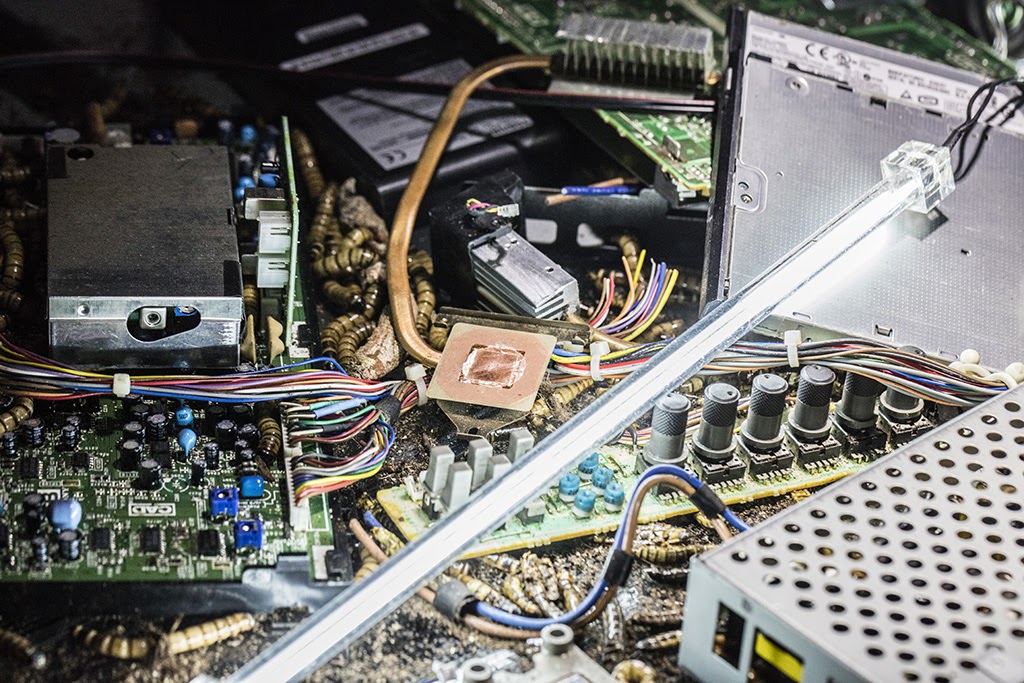

Jacob Remin, Harvesting the Rare Earth, 2017. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Jacob Remin, Harvesting the Rare Earth, 2017. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Rare Earth elements (or RREs) are a group of 17 metallic elements essential to sustaining the unrelenting global demand for new technological products. The materials have specific chemical and physical properties that make them useful in improving the performance of pretty much anything we associate with innovation nowadays: hybrid cars, smartphones, laptops, hi-tech televisions, sunglasses, lasers as well as less mainstream technology used by the military and medical profession.

Rare earths are extracted through opencast mining, they also generate radioactive waste and need be separated and purified at high ecological costs. Add to the picture that China has a near-monopoly (over 97% of the production) on mining REEs and the country is not a champion of environmental standards.

This near domination of a strategic resource means that China can control the exports of rare earth elements, drive the price of REEs up and disrupt manufacturing should any strong diplomatic disagreement with another country arise. That’s why America, Japan and Europe are getting increasingly concerned and are desperately looking for new sources of supply.

Japan, for example, is looking at recycling in order to recover rare earths from hard drives and other discarded electronics.

Jacob Remin, Harvesting the Rare Earth, 2017. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Jacob Remin, Harvesting the Rare Earth (Still from Jacob Remin’s drone footage of Agbogbloshie e-waste dump), 2017

Jacob Remin‘s latest artwork, Harvesting the Rare Earth, explores the REEs supply issue, while laying bare the consequences of our addiction to technology and reminding us that our cloud based, digital existence is firmly rooted into the ground.

The work presents a speculative near-future scenario, where a fictive biotech company has pioneered a sustainable biomining technology that uses genetically modified caterpillars to harvest rare earth elements in Agbogbloshies, the biggest and most notorious e-waste dump in the world.

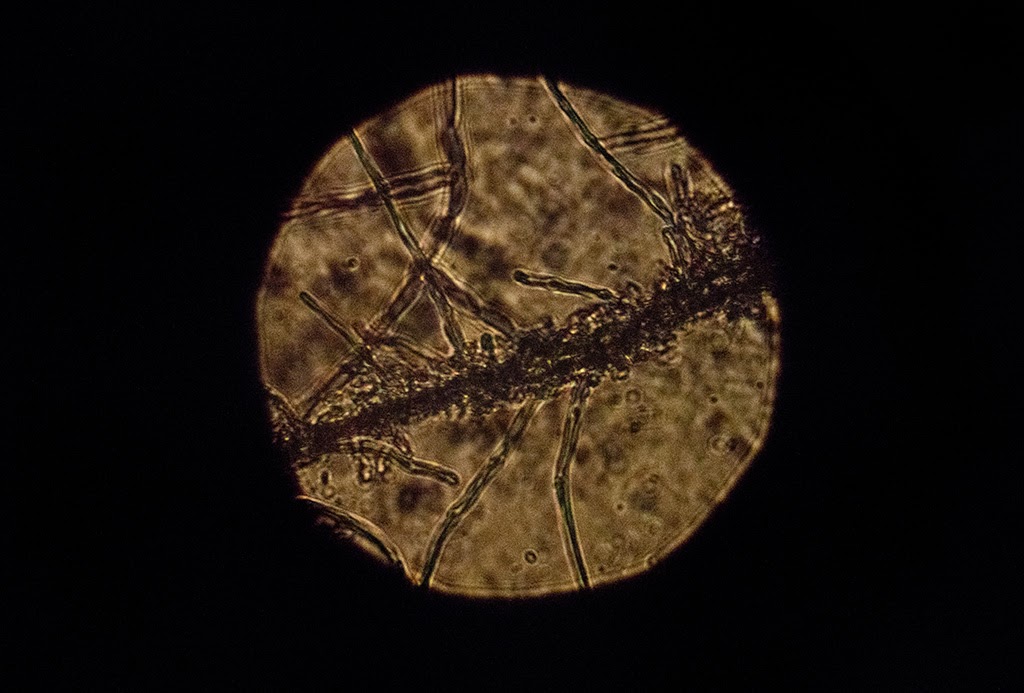

The recycling technology bears the poetic name of The Butterfly Solution. The remediation process would rely on 3 elements: a nutrient and chemical solution, an engineered fungi and an engineered butterfly.

Jacob Remin, Harvesting the Rare Earth, 2017. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Jacob Remin, Harvesting the Rare Earth, 2017. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

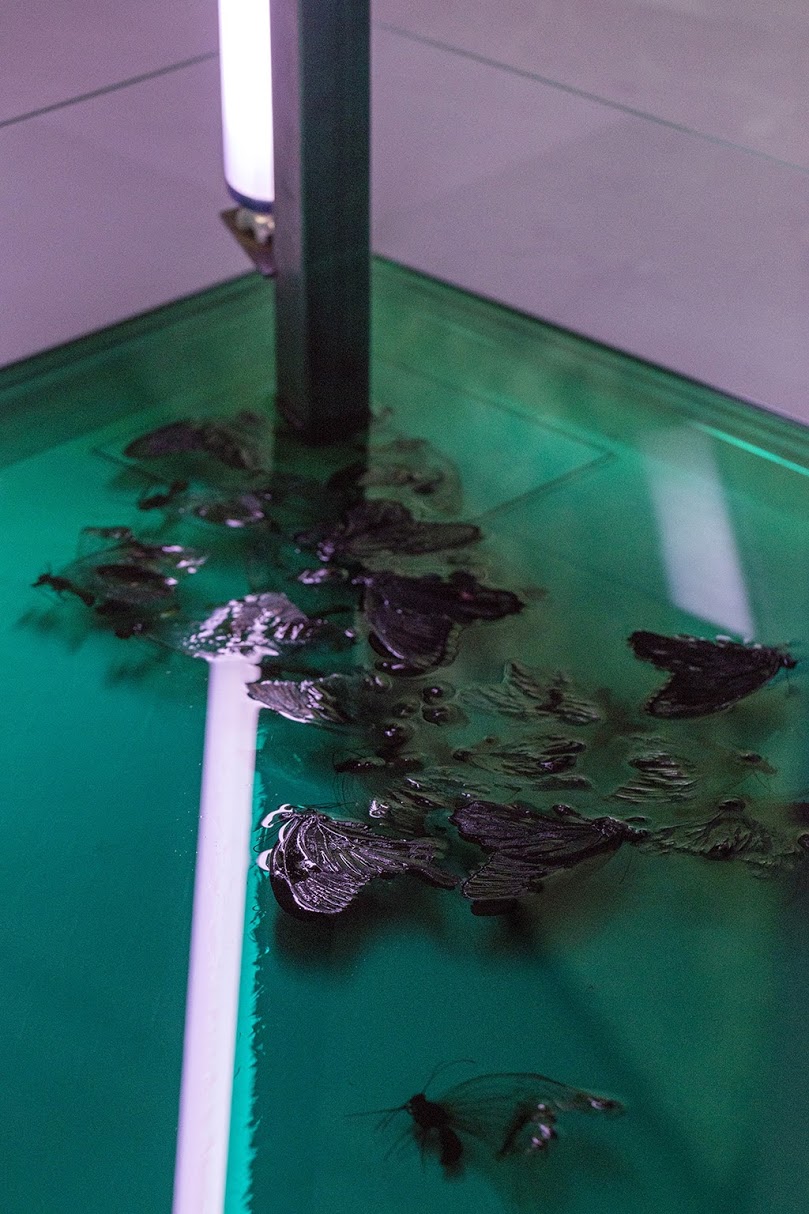

First, the nutrient solution is spread over the leftovers of the remains of the broken-down pieces of electronics. The chemicals from the solution then slowly dissolve the REEs present in the waste. Microscopic fungi feed of the nutrients in the solution and accumulate REEs in their tissues. The larvae of the butterfly feed on the fungi and will eventually morph into butterflies saturated with RE elements. The butterflies then take over. Because they are naturally attracted to light on the ultraviolet spectrum, they flock to UV light beacons scattered around the waste fields. The beacons are conveniently located at the center of harvest points. Once collected, the butterflies are put in an enzymatic acid solution that dissolves the organic matter of the insects. Finally, the rare earth elements are mechanically separated into clean mineral fractions ready for industrial applications.

The scenario might sound quite far-fetched but it is anchored in research related to bioremediation and biomining of rare earth elements. The artist also worked with biological engineer Martin Malthe Borch to develop the concept behind the biomining process. If you’re curious about the technological background, check out the draft version of their paper Harvesting the Rare Earth. Art-science research, reflections and discussion, it’s a fascinating read.

The installation of this speculative scenario takes the form of the reception and conference room of a near-future biotech company called Hybrid Ventures. The corporate design of the space contrasts starkly with other elements in the exhibition: the accumulations of dirt-covered electronic waste, the footage from a drone fly of Agbogbloshie, the caterpillars, etc.

Harvesting the Rare Earth presents a dream scenario in which the dirty business of recycling remains in countries located far away from our shores and consciences. The whole process has other, very reassuring, advantages. It has an innocuous and poetical name (The Butterfly Solution), it is undertaken in a seemingly ‘sustainable’ way and even better, the proposed technology never questions nor impedes our addiction to technology.

Jacob Remin, Harvesting the Rare Earth, 2017. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Jacob Remin, Harvesting the Rare Earth, 2017. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Harvesting the Rare Earth is currently on view at Overgaden in Copenhagen. I asked Jacob if he could give us more details about his work:

Hi Jacob! Harvesting the Rare Earth presents “a speculative near-future scenario, where mining companies are using genetically modified micro organisms to harvest rare earth elements from e-waste dumps around the world.” This sounds like an alluring scenario where mining is done in an eco-friendly way. It also echoes the importance of rare earth crucial for the development of so-called ‘clean’ tech such as wind turbines and batteries for electric cars. So is Harvesting the Rare Earth a positive vision of the future of mining, recycling and e-waste management?

Rare earth elements are crucial to so much more than clean tech. The electrochemical properties of rare earth elements are driving technology development in the 21st century: From lasers, over fiber optic cable to magnets, harddrives and screens. Our cloud-based, digital existence is closely connected to the earth.

While precision mining with bio engineered worms is certainly a cleaner way of getting rare earth elements than what we are currently doing today, the show also portrays the reality today, documenting the vast e-waste dump of Agbogbloshie, one of the places where the device you are reading this from goes to die. The exhibition tries to balance between a reassuring scenario where technological innovation satisfies our needs, but also exposes our increasing addiction to technology and the ecological implications of this addiction.

Jacob Remin, Harvesting the Rare Earth, 2017. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Jacob Remin, Harvesting the Rare Earth, 2017. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Jacob Remin, Harvesting the Rare Earth, 2017. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Could you take us through the form that this scenario takes in the exhibition space? Photos from the opening show glass tables with all sorts of objects….

The show takes form as a investment pitch for bio-tech company called “Hybrid Ventures”. When you enter, you enter the reception of the company with sofas, plants and an art sculpture in the corner. To your right, you find a conference room with rows of chairs, a speech podium, corporate branding and 3 podiums emanating drones. On the 3 podiums there are the 3 components of the company’s proposed “Butterfly solution”: 1 micro organism, 1 worm, 1 butterfly. In the corner there is another sofa group with headphones placed in front. When you listen to the headphones you learn about the business plan of “Hybrid Ventures”. In the other end of the gallery, through a narrow passage way, you enter the e-waste prototype: Electronics and worms in 5 glass vitrines, a large projection of drone recording from Agbogbloshie, Ghana and 1 giant bug zapper lamp, placed in another vitrine, full of dead butterflies and a green enzymatic acid solution.

Jacob Remin, Harvesting the Rare Earth, 2017. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

Why did you chose to use a fictive biotech company as the anchor of the installation? Do you think that fiction and speculation are more appropriate to communicate the questions that preoccupy you?

Discussing subjects like ecology, the global economy, necropolitics and the cloud is highly complex. Giving the exhibition a fictive near-future scenario makes things concrete, while at the same time supplies me with the freedom to choose whichever vantage point i prefer. Being a startup biotech company 5-10 years from now is the most interesting position i could imagine for discussing these issues.

In an interview with Backlisted, you said: This is an ongoing exploration for me: for instance, part of this show is an older piece called Material Meditation from 2010, which focuses exactly on the blurring borders between technology and nature. To me, all of these things are part of the equation—”nature is part of the problem”. Could you expand on this and explain what you meant by this idea that nature is part of the problem?

“Nature is part of the problem” is a quote by Timothy Morton. I am trying to broaden the view a bit from our traditional human-centered perspective.

Jacob Remin, Harvesting the Rare Earth, 2017. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

I read that the installation is accompanied by sounds created by Yann Coppier and Runar Magnusson. What is the role of the soundscape in this work?

I really enjoy working with sound in installations, and collaborating with Yann Coppier and Runar Magnusson has been a pleasure as always. To me, sound offers a possibility to talk in a much more suggestive manner, than say with images or text, and so the compositions in this show offers a suggestive underlining of the points I am trying to make. For instance we have installed the sound of an industrial fan inside a constructed pathway in the gallery leading to the e-waste prototype. The sound is a relative low rumble and white noise, played through transducers, making the pathway wall vibrate slightly. Since this is sound and therefore invisible, many people will probably not notice this, but it still works on a more subconscious level suggesting that this is “big industry”, ie. something fuels this which produces enough heat, that industrial scale cooling is needed.

I think you’ve been to Accra in Ghana, right? What did you learn about the issue at the core of your work while you were there? And how did you translate it in the installation?

Yes, I went to Accra, Ghana last year to film in Agbogbloshie, the worlds largest e-waste dump. I knew that many Danes were unaware that their electronic waste would end up in places like this but I was surprised to find that many local ghanians didn’t know that Agbogbloshie existed, and what went on there, even if it is quite large and very centrally placed. In many ways this was just another underlining of how disconnected we are from our trash and the physical footprint of our superslick lives; out sight, out of mind. We look at the world through technical systems and how this influences the human conditions is important to me. Documenting Agbogbloshie, I chose to film drone always facing north, camera always facing downwards, mimicking a google maps perspective.

And which books, articles, videos or other resources would you recommend to know more about the issues surrounding rare earth, e-waste, etc?

A Prehistory of the Cloud by Tung-Hui Hu and Rare Earth by Boris Ondreicka & Nadim Samman are both excellent books.

VIRTUAL PERCEPTION, with Jonas Lund (S), Morten Modin, Sif Itona Westerberg, Søren Thilo Funder, Jacob Remin, David Stjernholm, Ditte Ejlerskov and Hannah Heilmann. Photo by David Stjernholm

Any upcoming project, field or research or event you could share with us?

I just travelled trough Oslo, and was fortunate enough to see the exhibition Myths of the Marble at Henie Onstad Kunstsenter. Highly recommendable!

Also, I have 2 new pieces in the group show Virtual Perception in Huset for Kunst og Design, Holsterbro which features a list of several interesting Danish (and one Swedish) artist artists.

Thanks Jacob!

The exhibition Harvesting the Rare Earth remains open at Overgaden in Copenhagen 19 March 2017

Previously: Radioactive Ming vases echo our toxic dependency on electronics.