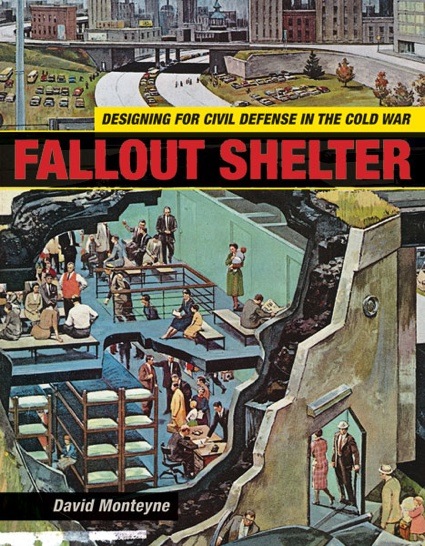

Fallout Shelter. Designing for Civil Defense in the Cold War, by David Monteyne, assistant professor in the Faculty of Environmental Design at the University of Calgary.

Publisher University of Minnesota Press writes: In Fallout Shelter, David Monteyne traces the partnership that developed between architects and civil defense authorities during the 1950s and 1960s. Officials in the federal government tasked with protecting American citizens and communities in the event of a nuclear attack relied on architects and urban planners to demonstrate the importance and efficacy of both purpose-built and ad hoc fallout shelters. For architects who participated in this federal effort, their involvement in the national security apparatus granted them expert status in the Cold War. Neither the civil defense bureaucracy nor the architectural profession was monolithic, however, and Monteyne shows that architecture for civil defense was a contested and often inconsistent project, reflecting specific assumptions about race, gender, class, and power.

Despite official rhetoric, civil defense planning in the United States was, ultimately, a failure due to a lack of federal funding, contradictions and ambiguities in fallout shelter design, and growing resistance to its political and cultural implications. Yet the partnership between architecture and civil defense, Monteyne argues, helped guide professional design practice and influenced the perception and use of urban and suburban spaces. One result was a much-maligned bunker architecture, which was not so much a particular style as a philosophy of building and urbanism that shifted focus from nuclear annihilation to urban unrest.

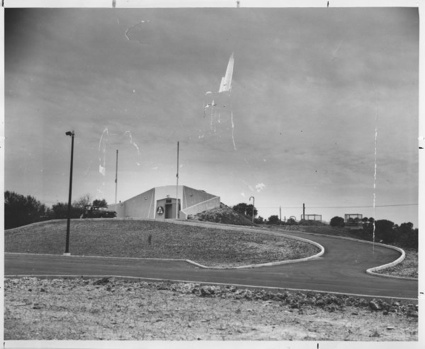

Civil Defense bunker, Lakefront, Undated. Photo: New Orleans (La.) Office of Civil Defense

Civil Defense bunker, Lakefront, Undated. Photo: New Orleans (La.) Office of Civil Defense

While reading the book, i was reminded of an American TV series from the early 1960s: The Twilight Zone. They called it La Quatrième Dimension where i lived. The episodes were part of a French tv programme from the 1980s that mixed science, scifi and pop culture. The two presenters, the twins Igor and Grichka Bogdanoff, were the coolest guys on this planet. I got a shock about an hour ago when one of the first results of a google search produced this! But i’m digressing. Some of the most memorable episodes of the Twilight Zone featured nuclear shelters, see for example Time Enough at Last and The Shelter. Atomic shelters were very exotic, very American, very eccentric to me. They were also sinister. Because of their design and purpose of course but also because of the era they embody and because of the scenarios built around them by the tv writers.

The Twilight Zone, The Shelter, 1961 (continues: part 2 and part 3)

The episodes of the Twilight Zone are works of fiction but they also echo some of the preoccupations and ethical dilemmas raised by many of the architects whose work is discussed in this book. Fallout Shelter. Designing for Civil Defense in the Cold War is first and foremost an architecture book but its content is also pertinent to readers who have a very limited interest in the discipline. The design and politics of fallout shelters spills onto other issues that characterized the early Cold War. From racial questions (the shelters were conceived for white American families living in suburbs and not so much for the people living in multi ethnic inner-cities or for ‘marauding Indians’) to the reluctance to spend tax money on social welfare. From urban dispersal to the exploration of new modes of urbanism (for example, Camp Century, ‘the city under the ice’.)

However, some of the issues raised and solutions brought forward at the time still (unsurprisingly) exert an impact on the world we live in today: the militarization of public edifice and spaces (called in the book ‘fortress urbanism’), the propaganda of fear, the top secret bunkers built by the government to protect members of the federal government and of the military reminded me of the ‘Blank Spots on the Map‘, etc.

Collier’s magazine cover from 1950 depicting a mushroom cloud over Manhattan (Chesley Bonestell)

Collier’s magazine cover from 1950 depicting a mushroom cloud over Manhattan (Chesley Bonestell)

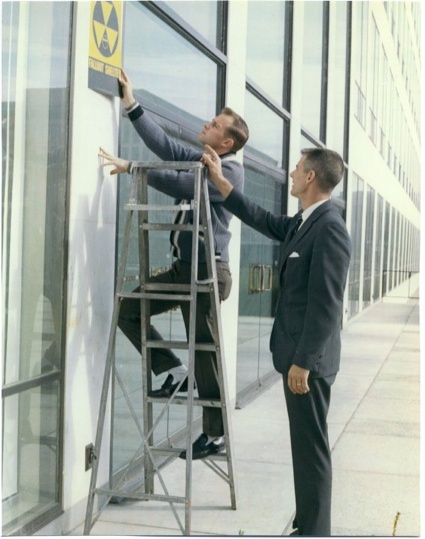

Posting a fallout shelter sign on a building in Washington, D.C. Image released to the public by the Department of Defense, Office of Civil Defense, December 1961. Image via District Fallout

Posting a fallout shelter sign on a building in Washington, D.C. Image released to the public by the Department of Defense, Office of Civil Defense, December 1961. Image via District Fallout

Here is the rough structure of the book: The first two chapters differentiate the approaches to civil defense taken in the 1950s an 1960s. While the 50s had little understanding of the impact of atomic weapon on the land and advised citizens to build their own shelters, the later decade admitted that little could be done to protect the population from the atomic blast itself and that only the fallout could be addressed which lead to a change of strategy that involved locating existing public buildings that could be used for communal protection. Chapter 3 examines more closely the planning process. Chapter 4 explores how architects approached (or brought a critical light on) the opportunities offered by civil defense work. Chapter 5 and 6 presents a series of architectural competitions, publications and programs launched to convince architects to plan for fallout shelters in new constructions. The last chapter studies in detail the building that inspired the book: the Boston City Hall.

Kallmann, McKinnell, & Knowles, Boston City Hall (photo)

Kallmann, McKinnell, & Knowles, Boston City Hall (photo)

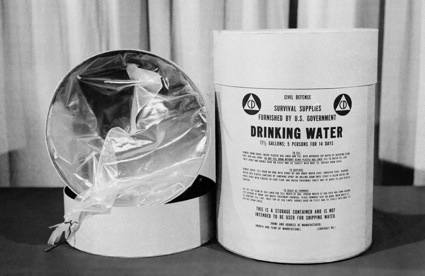

Fiber Drum and polyethylene liner provided by the department of defense office of civil defense for public fallout shelters. Each drum is filled with 17.5 gallons of water which will provide drinking water for 5 persons for 14 days. Photo taken on February 19, 1962. (AP Photo)

Fiber Drum and polyethylene liner provided by the department of defense office of civil defense for public fallout shelters. Each drum is filled with 17.5 gallons of water which will provide drinking water for 5 persons for 14 days. Photo taken on February 19, 1962. (AP Photo)

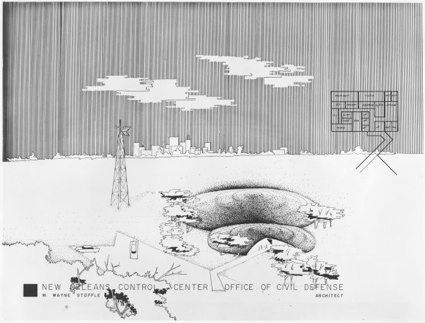

Architects’ Conception of New Orleans Civil Defense underground emergency control center to be located on the city’s outskirts as a protective measure, 1960. Photo: New Orleans (La.) Office of Civil Defense

Architects’ Conception of New Orleans Civil Defense underground emergency control center to be located on the city’s outskirts as a protective measure, 1960. Photo: New Orleans (La.) Office of Civil Defense

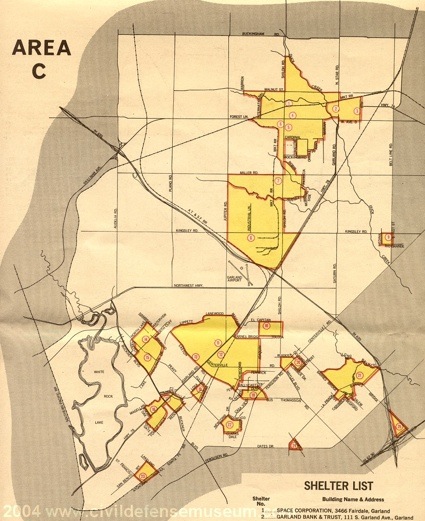

Community Shelter Plan depicting a portion of Dallas, Texas. List of shelter addresses on the left. In yellow, drainage areas people could walk to shelters; in red areas they would need to drive their cars. In white, no fallout shelter is available. Image Civil Defense Museum

Community Shelter Plan depicting a portion of Dallas, Texas. List of shelter addresses on the left. In yellow, drainage areas people could walk to shelters; in red areas they would need to drive their cars. In white, no fallout shelter is available. Image Civil Defense Museum

Federal Civil Defense Administration Presents Lets Face It, No date

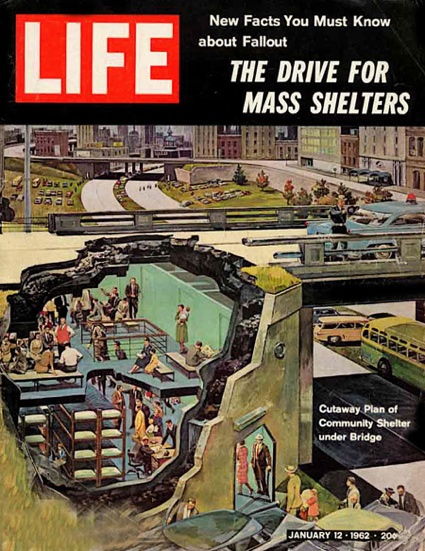

Life January 12, 1962

Life January 12, 1962

Source image on the homepage: Atomic annihilation.