Digital Art. 1960s to Now. Edited by digital art curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum Pita Arreola, senior curator of design and digital at the V&A Corinna Gardner and digital art curator at the V&A Melanie Lenz.

A new history of digital art from the 1960s to the present day, with decade-by-decade essays exploring evolving digital art practices, alongside interviews with artists, gallerists, museum curators and collectors.

Another book about digital art!? Yes, but this one stands out from the sea of similar publications. It is straightforward enough to interest the neophyte but brisk and bold enough to offer new perspectives to readers who have read their fair share of publications about digital art. It covers history through a series of surprisingly concise but efficient essays that condense the digital art milestones and situate them within evolving social, cultural and technological contexts.

The highlight of the book (for me) is all the content that accompany the essays. In particular the series of interviews and discussions with artists, gallerists, museum curators and collectors offering insights into the challenges, interrogations and joys of their practice.

Julieta Gil, Nuestra victoria, 2019-20

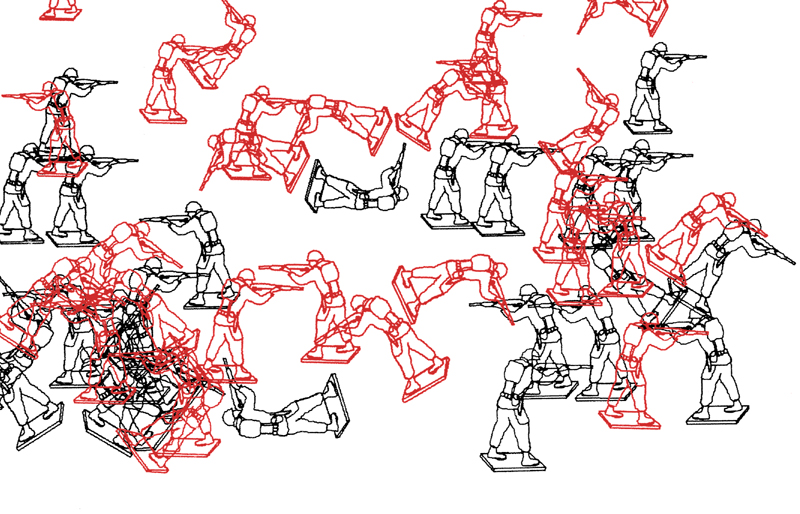

Charles Csuri, Random War (detail), 1967/2006

The section dedicated to the 1960s-1970s reflects on the role of scientific and military technology in shaping the works of early computer artists. The anecdote that surprised me the most in the essay regards the fact that in the 1960s already, people were asked to choose between work by a machine and a similar work by an artist. A. Michael Noll’s 1964 work Computer Composition with Lines, for example, emulated the painting “Composition With Lines” by Piet Mondrian. When reproductions of both works were shown to 100 people, the majority preferred the computer version and believed it was done by Mondrian.

Lawrence Lek, FTSE (Farsight Stock Exchange), 2019

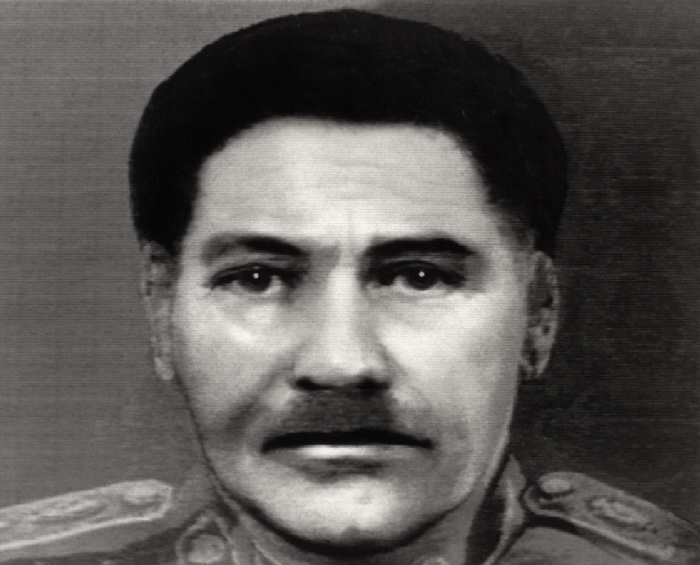

Nancy Burson, Big Brother, 1983. A composite of photos of some of 20th Century dictators: Stalin, Mussolini, Mao, Hitler and Khomeini

Analisai Cordeiro, M 3X3, 1973. Photo: Silvio M. Zancheti

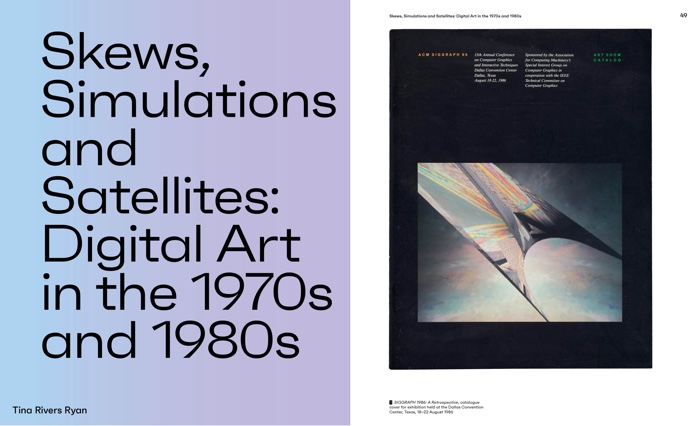

The essay about digital art in the 1970s-1980s explores the influence that easier access to computer graphic, 3D modelling and other computing technology had on artistic production. The text is followed by a conversation between Lawrence Lek and David Em. I loved how Lek, born in 91, set aside his own achievements in the field of films, gaming and AI and showed genuine curiosity towards Em, an artist who started working with digital media before there were personal computers and became the first artist to produce navigable virtual worlds in 1977 at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, where he was Artist in Residence from 1976 to 1988. Together, they exchange about automation, control, AI, what 3D navigable environments looked like in the 70s and 80s. Their conversation did a great job at recreating the experimental atmosphere of the time and made it clear how much today’s artists owe to the art pioneers of the 70s and 80s.

Dr. Richard Barbrook about The Californian Ideology he wrote with (the much-missed) Andy Cameron

Shu Lea Cheang, Brandon, 1998-9

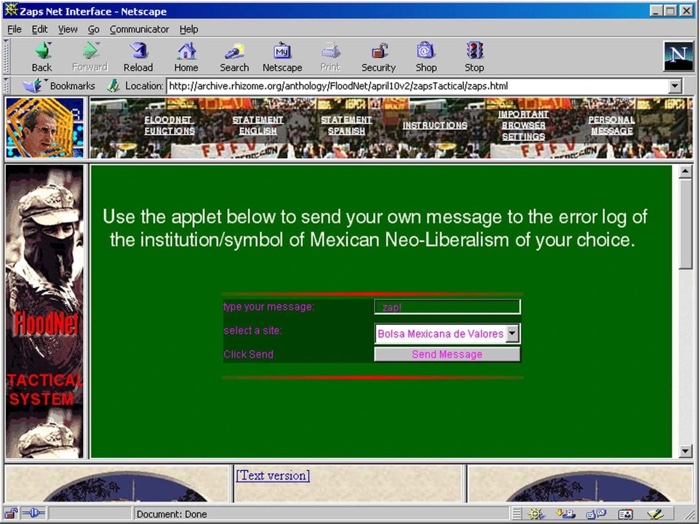

Written by Ruth Catlow and Marc Garrett from Furtherfield, the essay covering digital art in the 1990s-2000s manages to flesh out what artistic practices looked like and felt like at the time. Against the backdrop of Saatchi’s gluttonous art collecting, hacktivists and grassroots communities’ experimented with tools of mass communication to develop new modes of cooperation, hack networks, invent net art, bolster countercultures, etc. The text made me wish i had taken part in that exciting moment in digital art.

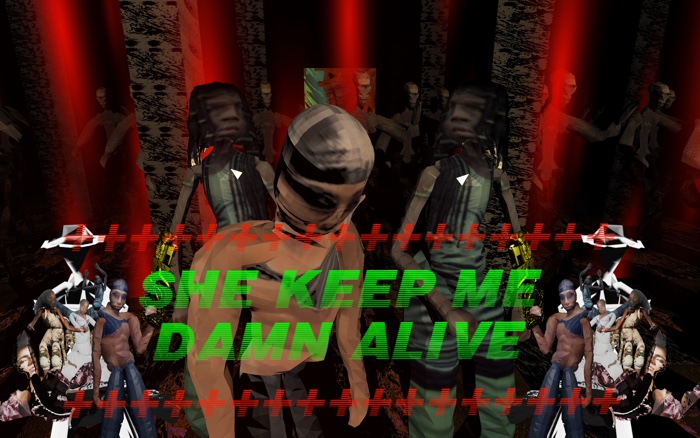

Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley, SHE KEEPS ME DAMN ALIVE, 2019

Sarah Friend, Lifeforms, 2021

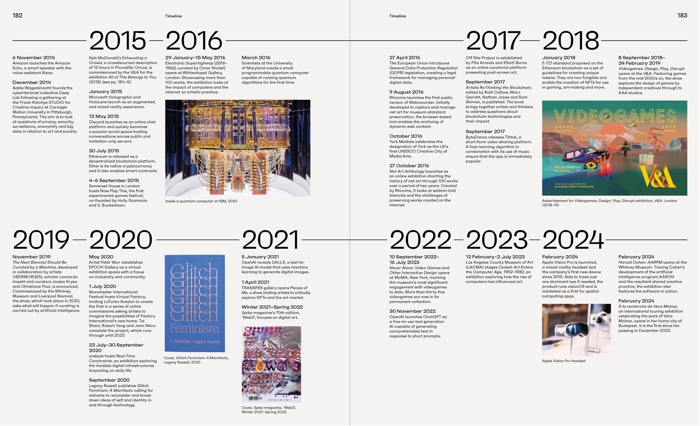

Landing on the “2000s to Now” chapter is brutal. After the artistic experimentations with new tools and new modes of cooperation and network hacking that characterised the 1990s, the new panorama of corporatisation of online space is dispiriting. Yet, the millennium also saw the emergence of Creative Commons and artists fighting back, repurposing networks, reclaiming online space from data-driven corporate strategies and making their own practices more ethical.

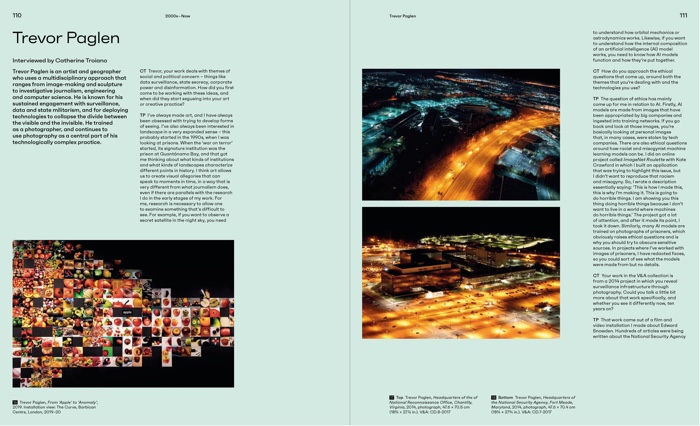

The three interviews accompanying that chapter illustrate the wide range of contemporary practices. Trevor Paglen discusses secret satellites in the night sky, AI models, surveillance infrastructure and the politics of image-making. Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley explains how she deconstructs video games as an artistic medium to archive Black and trans experiences. Harm van den Dorpel and Sarah Friend exchange ideas about the financial value of art and blockchain, selling digital goods online, the collectability of digital art, the materialisation of digital works and AI art.

Erica Scourti, Life in AdWords, 2012-13

Morehshin Allahyari, Moon-faced, 2022-23. Photo: Pinelopi Gerasimou

Jason Isolini, The Ballad of a Laborer, 2020-23

The historical chapters are followed by three conversations between experts on key aspects of digital art: accessing digital tools, self-organising communities and, finally, collecting and exhibiting digital works.

In their conversation about technology, access and creative tools, artists Ibiye Camp, William Latham and Manfred Mohr talk about making your own tools. Ibiye brought a much needed non-Western centric perspective when she explained that not everyone has access to all the tools or to the complete internet in African countries, for example. Which means that people are creative and reappropriate the tools but often without all the instruments that we enjoy. It was also interesting to read Mohr explain how, in the early days of his long digital art practice, the art world was very aggressive towards his work. He was accused of being a terrorist and of destroying art with military machines.

Electronic Disturbance Theater, FloodNet, 1998

In the second conversation, designer and technologist Mindy Seu, artist Paul Brown and curator Doreen Ríos discuss DIWO communities. Among the highlights of the exchanges are Seu talking about the crowdsourced Cyberfeminism Index, Ríos drawing parallels between algorithmic thinking and Zapatistas indigenous oral traditions and highlighting Mexico’s culture of building one’s own machines from scratch.

Finally, Lisa Long, artistic director of Julia Stoschek Foundation, Kelani Nicole, Director of TRANSFER and Nimrod Vardi, Creative Director of arebyte discuss what it means to present, collect and preserve digital art. From the importance of taking risks to making sure that different audiences feel welcome in the physical spaces. From being in conversation with institutions to functioning outside the art market.

Digital Art. 1960s to Now is visually irresistible, concise yet packed with interesting anecdotes. You can sense that the editors put a lot of effort into trying to avoid the accusation of Western-centrism. I don’t think that the book was too Western-centric, but it might be a bit too Anglo-centric (or whatever you say to indicate a wealthy English-speaking countries perspective.) As a native speaker of French living in Italy, I would probably have chosen different landmarks, but we all have our own biases and dead angles. I will, however, be forever grateful to the editors of the book for introducing me to the work and thoughts of Mindy Seu, Ibiye Camp and Doreen Ríos. I found their contributions fascinating. Probably because my perspective is very Western-centred.

Ibiye Camp, Area Snap Devices (Data: The New Black Gold)

LaTurbo Avedon, Your Progress Will be Saved, 2020-ongoing