Recent European immigration policies seem to be mostly dedicated to making external borders as impenetrable as possible, through the hardening of the conditions of entry and, most notably since the 2015 refugee panic, through naval operations in the Mediterranean and the erection of fences and walls. The numbers of migrants reaching European shores in search of asylum have dropped sharply over the past couple of years but the desire to deny them a chance to seek asylum is still fueling the xenophobic rants of far-right politicians like Viktor Orban and Matteo Salvini.

Dani Ploeger, SMART FENCE at Bruthaus Gallery, 2019

Dani Ploeger, Still from Border Operation, 2018-19, HD video, 3′. Documentation of action at Hungarian border fence

Artist Dani Ploeger has been looking at the fences recently built to toughen “Fortress Europe.” In particular the ones that use heat and movement sensors, sophisticated cameras and other so-called ‘smart’ technologies to shut off “illegal immigrants.” The hi-tech terminology used to describe theses fences obscure their inherent violence. Moreover, Ploeger writes, “their framing as supposedly clean and precise technologies is symptomatic of a broader cultural practice that uses narratives of technologization to justify means of violence” (think of the military drones and their supposedly surgical precision).

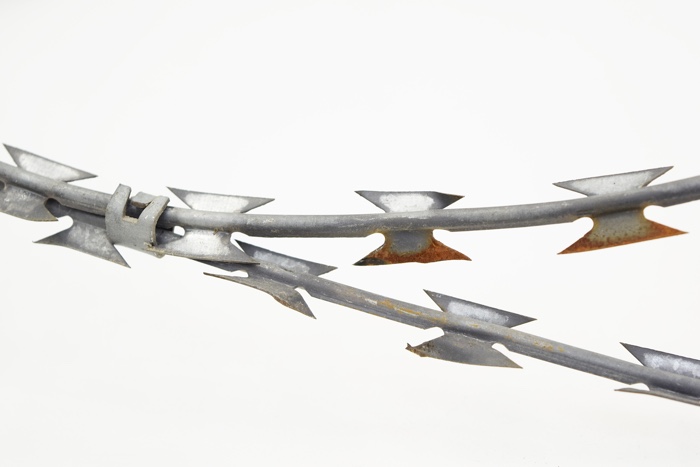

Last December, the artist traveled to the fortified border fence that Hungary had raised along its southern border with Serbia to keep out migrants and asylum seekers. The barbed-wire is capable of delivering electric shocks and is equipped with heat sensors, cameras and loudspeakers that shout inhospitable messages in several languages.

Once at the border fence, Ploeger cut off and ran away with a piece of razor wire from the border fence. This was a daring action: damaging the border fence is a criminal offence under Hungarian law.

Dani Ploeger, European Studies #1 (sensors). Exhibition view at Bruthaus Gallery. Photo by Alexia Manzano

Dani Ploeger, European Studies #1 (sensors). Exhibition view at Bruthaus Gallery. Photo by Alexia Manzano

Ploeger recently exhibited that piece of fence as well as a series of related works at Bruthaus Gallery in Belgium. His SMART FENCE project uses old and new media, from celluloid film to augmented reality, to explore the way we delegate our responsibility towards asylum-seekers to these tech-enhanced structures. Along the way, the artist also attempts to deconstruct the techno-ideologies that are often inscribed in these technologies of control and exclusion.

Dani Ploeger, SMART FENCE. Exhibition view at Bruthaus Gallery. Photo by Alexia Manzano

The exhibition at Bruthaus Gallery is sadly over but i got in touch with the artist a couple of weeks ago to know more about SMART FENCE:

Hi Dani! I often have the feeling that we are a bit hypocritical in Europe, at least in the areas that are not in close proximity to these new borders. We point the finger at the US-Mexico wall and turn a bind eye at our own manifestations of intolerance and inhospitality. Do you have any idea about how much the European public is concerned by these European border fences?

I was struck by how many visitors of the exhibition seemed to know very little to nothing about the border fences that have been erected around the EU in recent years, especially considering how much attention the Hungarian border project has received in the media. I wonder whether this is because many just don’t engage much with international news reports or if they forget news events quickly due to the constant bombardment with spectacular and shocking information in networked culture (Paul Virilio discusses this latter phenomenon in his book The Administration of Fear, 2012). Either way, I didn’t get the impression that many people assess the current discussions around the US-Mexico wall in relation to recent border reinforcement projects in the EU. This impression is just based on anecdotal experiences in my direct surroundings though. I don’t really know about ‘the European public’ in general, if such thing exists.

Possibly more disturbing than the finger pointing towards the US, I find the recurring suggestion that the Hungarian border fence would merely be a manifestation of the backwards politics of Victor Orban’s nationalist-conservative government and hence in essence actually be a very ‘un-European’ project. This perspective ignores that Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, is also active at the Hungarian border fence and that Greece, Spain and Latvia, among others, have built or are building similar fences, although these have not received as much media attention. In the end, these fences are quite convenient to many governments across the EU that want to restrict immigration.

Dani Ploeger, Border Operation, 2018-19. Exhibition view at Bruthaus Gallery. Photo by Alexia Manzano

What is amusing in the video Border Operation is that you’re stealing a piece of razor wire and you’re doing in broad day light and don’t seem to be in great hurry, even when the car with the security officers arrives. Did you know what you were risking? And do you think that it would have been ok because you’re an artist so you have some licence?

Interesting you see it like that. What I found somewhat funny is the indecisive and confused behaviour of the border patrol officers after I have left and they are just standing around, unable to do anything substantial because they are stuck behind their own fence. While I was at the fence, I was actually scared shitless, especially when the alarm loudspeakers switched on and the patrol car arrived, all within one minute from when I first touched the fence. My glove was stuck in the bit of razor wire I was trying to cut off though, and I was really quite determined not to go home empty handed, so that kept me a few seconds longer after they arrived. One of the guards was only about a metre and a half away on the other side of the fence though, and yelling at me, so I was close to leaving my glove behind and running off.

I had deliberately approached the fence slowly and casually before starting to cut in order not to make my intentions obvious right away. I figured that if I would run towards the fence through the 300 meters of open field next to it the video surveillance observers would be alarmed right away. I had planned and timed the action carefully the day before, based on an examination of the area around the fence, the frequency of the patrols and a little practice with my bolt cutter. My camera was attached upside down in a tree and my packaging material for the wire, first aid kit and various other materials were hidden behind the ruin of a house across the field. I did my best to stay cool during the action and to cut slowly and precisely without panicking. Nevertheless, I was so excited that I messed up and cut through a wrong bit at first (cutting concertina razor wire somehow isn’t as simple as it appears), struggled to get through the steel wire with my tiny cutter, and then I was surprised by how quickly the guards arrived. They seemed to come from nowhere.

A tricky thing was that the fence stands a short distance inside Hungarian territory, which means that border patrol officers may use pepper spray or fire rubber bullets at people who are messing with the fence from the outside. They can also operate on the outside if they go out through a gate about 100 meters from where I was. Therefore, I went away from the fence as quickly as possible once I got my bit of wire, and ran back to Serbian soil. In Serbia, I still had to walk for about half an hour to reach the main road though, partly through open fields. I hadn’t been able to find out through my contacts at the Serbian Commissariat for Refugees and Migration if the Hungarian border force is in contact with Serbian police, so this walk wasn’t very relaxing either. I had identified a few hide-outs along the way in case police would show up.

Damaging the border fence has been criminalized in Hungary in 2015, so I guess that in Hungary I would now be a fugitive criminal. Getting caught would probably have gotten me into some serious trouble and I don’t think saying that I’m an artist would have convinced them to just let me go.

In the end, I don’t believe they would push for a serious prison sentence or something like that though, both because I can’t imagine they’d find a single person action relevant enough and because it would lead to tensions with other EU countries. So rather than me being an artist I think my EU passport would have given me some leeway.

I actually think I was mainly scared to get a serious beating, or just in general to get caught by an unknown authority for doing something illegal. This is also where one of the most relevant aspects of doing this action lies for me.

When I watched video reportages about migrants cutting holes in the fence and running across, sometimes with entire families including small children, it hadn’t looked that scary to me. Thinking about what extreme challenges and dangers these people would have encountered on their journeys towards this border, getting rid of a bit of barbed wire and running across a few meters of border strip, with apparently the only serious risk being sent back, somehow seemed to be among the lesser challenges.

Considering how scared I was myself while merely stealing a bit of wire from this fence – not even trying to cross – makes apparent the extreme contrast between the relatively fear- and threat-free life many (Western) Europeans like myself are used to in comparison with the environments many migrants navigate. In this context, the lighthearted way in which some people and media speak of the supposedly gratuitous motivations of migrants traveling to Europe appears ridiculous: this is not a journey one would choose to undertake if the living conditions in the home country would be bearable.

Dani Ploeger, Sensitive Barrier (razor wire from Hungarian border, movement detector, electro-motor), 2019. Photo by Alexia Manzano

Dani Ploeger, Sensitive Barrier (razor wire from Hungarian border, movement detector, electro-motor), 2019. Photo by Alexia Manzano

Dani Ploeger, Sensitive Barrier (razor wire from Hungarian border, movement detector, electro-motor), 2019. Photo by Alexia Manzano

I was very interested in the extract in the press material that mentions the violence that is enacted on humans and non-human animals. Could you explain how non-human animals suffer from the erection of these ‘smart fences’?

Many animals, such as red deer, bears and wolves, used to have their grazing, hunting and migration routes through parts of EU borders that have now become impenetrable. The issue is not only that animals are no longer able to cross, but also that razor wire, which is the main component of the border fences throughout, is designed to deter humans. It is explicitly not intended for use against animals, because, unlike traditional barbed wire, they easily get stuck in it and die.

Dani Ploeger, European Studies #2 (wire). Exhibition view at Bruthaus Gallery. Photo by Alexia Manzano

Dani Ploeger, European Studies #2 (wire). Exhibition view at Bruthaus Gallery. Photo by Alexia Manzano

The AR technology used in European Studies #2 (wire) “was developed in collaboration with the AURORA project at the University of Applied Sciences Berlin with support from the European Union.” Isn’t it a bit ironic that the EU would contribute to a project that openly questions the management of its borders? Was everyone comfortable with the idea that you used EU money to criticise border control?

This irony is important to me. The EU has an extensive and complex bureaucracy that regulates and manages funding for research, arts and other things. I see this as an important reason why there usually isn’t too much worrying among researchers or art producers about policy-critical work as part of funded research or art projects, as long as the work adheres to the immediate rules and regulations for the management of the grant. I.e. if there isn’t a written rule that says ‘your research may not criticize EU policies’ all is fine, because grant holders will be monitored and assessed by peers and bureaucrats, rather than politicians or other people with significant policy making power. This leaves some space to use funding for things that might go against the immediate interests of the Union.

At the same time, we shouldn’t overstate this critical or subversive potential though. In the end, actions like mine are usually only possible a long way down in the ‘funding-hierarchy’. My AR app was a tiny sub-project in the context of a large EU-funded research project. This larger project, the design and management of which I am not involved in, was the outcome of a successful bid under the “Strengthening the innovation potential in culture” scheme of the European Fund for Regional Development. As the title of the scheme already suggests, research projects will only be funded if their design demonstrates detailed and far-going endorsement of the economic-growth-driven interests that form an important aspect of the European Union’s raison d’être.

So I’d actually say that, in the end, the true irony of the seemingly subversive use of EU funding for my project primarily concerns the way in which a lot of critical artwork, including my own, is intertwined with government support structures for research and art that are increasingly driven by clearly defined economic objectives. These objectives are also reflected in restrictive migration policies, which are oftentimes based on prioritizing cutting costs over humanitarian considerations.

To what extent does the ‘successful artist’ of a neo-liberal cultural landscape (i.e. the one who gets access to funding and is exposed at funded events and venues) become complicit in the economy-cultural complex that ultimately shares responsibility for the excesses of violence and neo-colonial policies on and beyond the borders of the EU or, more generally, the Global North?

Dani Ploeger, Sensitive Barrier, detail (razor wire from Hungarian border, movement detector, electro-motor), 2019. Photo by Alexia Manzano

These ‘smart’ technologies of ‘defense’ and the way they function elude visual representation. They make migration almost abstract. Your works, on the other hand, make their violence almost palpable. Have you not been tempted at any point to make the connection between the human and non-human animals who suffer from the deployment of these technologies more obvious and maybe also more (easily) emotional by adding the presence of migrants trying to go through them?

Many journalists and artists have done work that focuses directly on the human suffering in the context of these structures (suffering of non-human animals not so much). This work is very important, among others to counter the tendency to imagine migration as some kind of abstract phenomenon as you point out. But I think there are also aspects of the current problematics around migration that cannot be addressed adequately by this work, and which require different approaches.

Firstly, when the attention is focused on representations of migrants trying to cross the fence, architectural and technological aspects tend to move to the background. This is understandable and desirable – thank god engagement with human experience prevails over barbed wire and motion detectors – but it also means that the significant role of narratives and applications of technology in the ‘management’ of migration and territorial control remain under-examined.

Secondly, as I already mentioned above, I often find that when watching video and photo representations of migrants trying to break through these border fences the places and situations paradoxically seem a lot less threatening and violent than they actually are experienced in a material encounter. The material presence and digital close-up views of razor wire and the quasi-nostalgic analogue photographs of sensor installations in my work do by no means give access to the experience of encountering the border fence as a migrant. But I do hope that they offer an additional way to engage with the violent implications of the desire for closed borders, an engagement that operates more through a sense of haptic visuality, rather than emotional narratives.

Any upcoming project or field of research you’d like to share with us?

I see the work I presented at Bruthaus Gallery as the beginning of a longer project that looks into borders, technologies and their narratives, so I will probably make more work around this theme over the next year or so. In addition to the video I exhibited now, I made a 3D video recording of the action at the Hungarian border from first-person perspective with two action cams that were attached to my forehead. I will use this footage to make a work for VR headset which will engage more with the experience of stress and fear that I mentioned in response to your earlier question. Another thing I am working on at the moment is an AR app for public space. When you point your device at a replica of a sign from the border fence that reads “CAUTION: Electric fence” the app will construct a life-size 3D model of the border fence around this, so you are standing right next to it.

Later in the year, I will make a new work for a group exhibition at Kunstraum Kreuzberg/Bethanien in Berlin, titled Weapons of Art. For this, I am planning to travel to another part of the EU to look for fencing, but I don’t want to say anything more about that yet.

Thanks Dani!

Previous works by Dani Ploeger: e-waste, porn, ecology & warfare. An interview with Dani Ploeger and Global control, macho technology and the Krampus. Notes from the RIXC Open Fields conference.

See also: The System of Systems: technology and bureaucracy in the asylum seeking process in Europe, Watching You Watching Me. A Photographic Response to Surveillance and Transnationalisms – Bodies, Borders, and Technology. Part 2. The conference.