The New Curator, by Natasha Hoare, Coline Milliard, Rafal Niemojewski, Ben Borthwick and Jonathan Watkins.

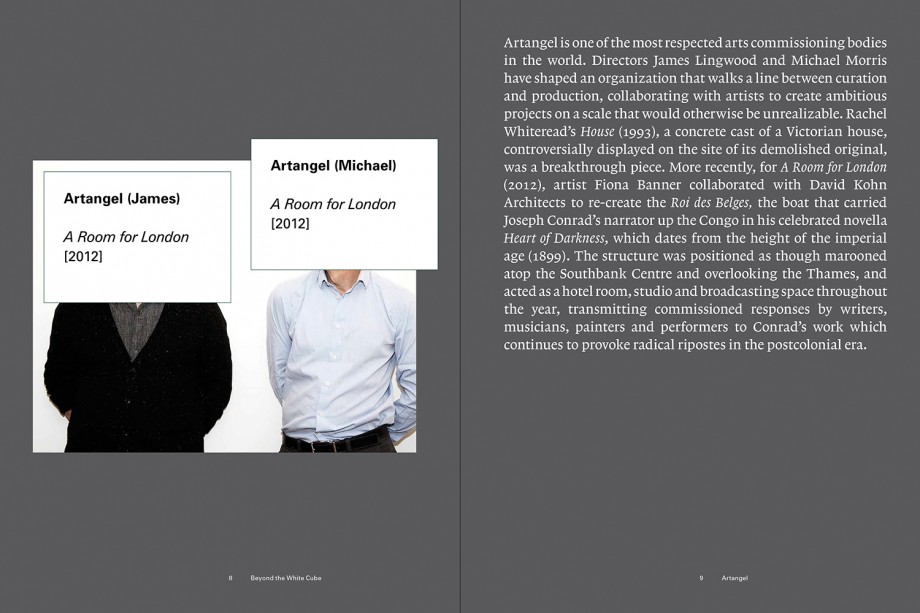

Publisher Laurence King writes: How many times have you heard the term ‘curate’ in the past few years? But what exactly does it mean? Curating has been a key concept both in and outside the art world in the past few years, with the remit of what a curator does having changed and expanded with each new exhibition or biennale. With an emphasis on the ‘now’ and the most recent exhibitions, this book examines the variety and richness of curating practices today, from public commissions by Art Angel to experimental projects such as the ‘Ghetto Biennale’ in Haiti or the Rhizome digital archive.

Each highly illustrated case study is structured around an interview with the curator responsible for the show. The text both tells the story of the show’s making and fills in background information about the curator’s work.

Francis Alÿs’ Seven Walks, 27 September 2005 – 20 November 2005. Photo Artangel

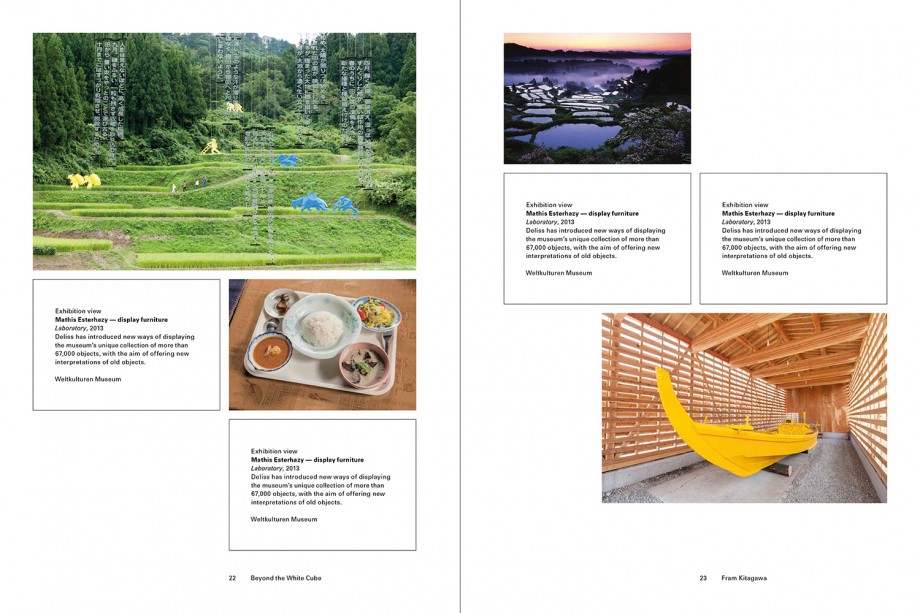

Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, The Rice Field, 2000-ongoing. Photo: Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial

This one’s the good surprise of the month. I thought i should read the book for my own personal information, to stay in touch with the distant and daunting world of contemporary world and its glamorous actors. I expected pomposity, dense vocabulary and an otherwise fairly uneventful read. The book turned out to be a gem. It’s a collection of interviews with curators whose ballsy experiments are on par with the work of some of today’s most intrepid artists.

There’s a total of 26 interviews. One of them with Broomberg and Chanarin. Broomberg and Chanarin! Yes please!

I was surprised to read that the role of the curator is a fairly new one. The discipline emerged in its current form in the 1960 only and the first academic curatorial studies programmes were established in the early 1990s. In the meantime, the profession has evolved very fast. The ‘old curator’ was and is still the keeper of the museum or art collection. The new model of curator is often independent from museums, lives on temporary contracts, is expected to have many talents and functions, and is flying from one place to another in order to work on the production, dissemination and contextualization of art works and events. As the editors write, “while artists push boundaries, curators make ways for them to exist into the world.”

The New Curator offers a snapshot of the places and spaces occupied and disrupted by curators today. The interviews are lively and approach questions that go from how to challenge the sterility of the art fair format to how much curators get involved into the conceptual development of a new commission or how difficult it is to find funding for large-scale projects.

The curatorial practice is divided into four chapters: Beyond the White Cube, Rethinking the Biennale Model, Towards a Radical Institution and Transcending Boundaries. The chapters tend to overlap and confuse each other but that’s probably because many of the curators featured in the book are busy shaking up the art experience on so many fronts.

Mike Kelley, Mobile Homestead, Detroit, USA, 24 September 2010 – ongoing. Photo Artangel

Michael Landy, Break Down, Oxford Street, London, 10 February 2001 – 24 February 2001. Photo Artangel

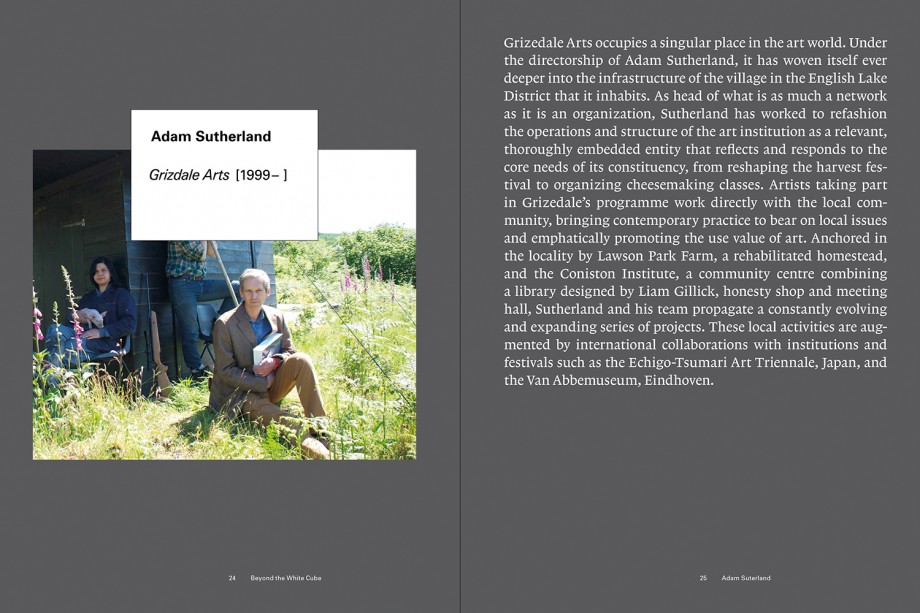

The first group of curators illustrates the desire to break away from the constraints of the white cube space. Their efforts allow art to invigorate a rural region struggling with depopulation (Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale), turn ridiculously ambitious ideas into large scale experiments (Artangel) or interlace international exhibition with cheese making, gardening and anything that characterize everyday local life in a National Park (Grizedale Arts in the Lake District, England.)

A second group of curators attempts to give new meanings, formats and value to the much maligned and much inflated model of the art biennial. Two of the examples seemed particularly radical to me. The first one is the Ghetto Biennale, founded by Leah Gordon. The event takes place in the slums of Port-au-Prince in Haiti and challenges artists to create works using the kind of poverty materials found in the ghetto.

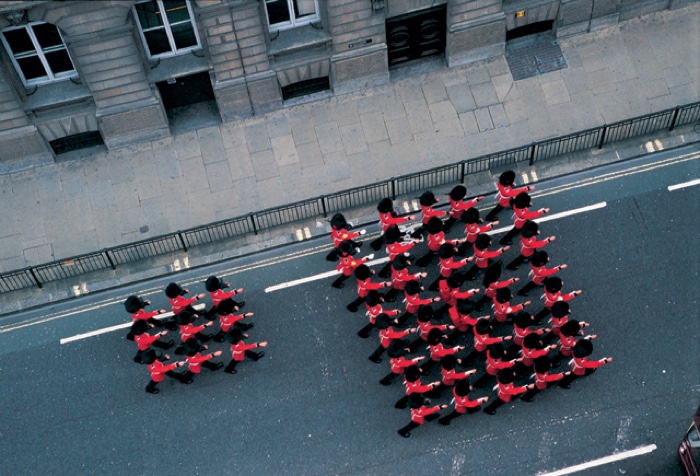

Charles Freger, Légion étrangère, 5. Alias: Installation views Bunkier Sztuki, Krakow PhotoMonth 2011

The second example is the edition of the Kraków Photomonth guest curated by Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin. Their exhibition, Alias, presented new works by artists working under alternative identities created for them by commissioned writers:

Twenty-three writers (of fiction, fact and medical history) were commissioned each to create a text describing an invented persona, which was then assigned to a visual artist to inhabit. The work that accompanies these texts is the result of each individual artist’s residency in their fictitious character.

90% of the artists didn’t really get on board and made their work literally. Which probably came as no surprise to Broomberg and Chanarin who had framed the exhibition as an experiment set up to fail.

The third group of curators aims at establishing new, radical institutions that illuminate contemporary political situations and attempt to address bigger audience without sacrificing the depth and complexity of the art discourse.

The stand out experiment was undoubtedly the project Picasso in Palestine conceived by artist Khaled Hourani and curator Charles Esche:

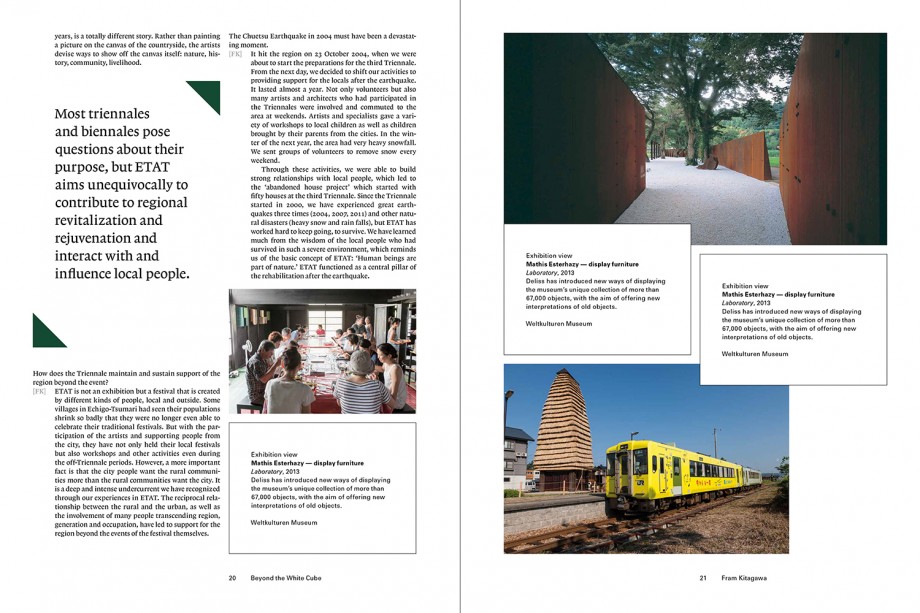

Picasso in Palestine, 2011, installation view. Photo credit: Khaled Jarar

On the road to Ramallah, June 2011: ‘Picasso in Palestine’ exhibition advertised on a roadside hoarding. Photograph by Charles Esche

In 2011, Picasso’s Buste de Femme (1943), one of the most iconic works from the collection of the Van Abbemuseum, traveled from Eindhoven to the International Art Academy Palestine in Ramallah. An important part of the project consisted in documenting all the experiences involved in the preparation, insurance, shipping and display of the painting in the Palestinian city.

The experiment involved far more than just the shipping and hanging of a painting. Because of the occupation and limitations on Palestinian sovereignty, the loan from one museum to another suddenly took on a political, diplomatic and military character. It involved insuring a masterpiece against Israeli incursions into the West Bank city, clearing passages through checkpoints, facing difficult road conditions, dealing with a constantly shifting political situation, convincing Israeli officials to help so that the journey went smoothly, etc. The project demonstrated how art institutions can use their power and prestige to infiltrate a war zone.

The last type of curatorial practice looks at how curators are ‘transcending boundaries’ and opening new possibilities for art itself.

Charles Campbell, Actor Boy: Fractal Engagement. Part of ‘En Mas’: Carnival and Performance Art of the Caribbean curated by Claire Tancons in 2014

The two interviews i found most interesting involved Claire Tancons explaining how her art practice explores the political aesthetics of carnival, processions, civic rituals and other popular movements and Michael Connor commenting on how he and Dragan Espenschied are giving a historical perspective to Rhizome‘s net art collection.

Inside the book: