The Mata gallery. Photo: Bruno Magalhães.

The Mata gallery. Photo: Bruno Magalhães.

Sorry for the long silence, this visit to Brazil is far more absorbing than i expected. On Sunday, the organizers of arte.mov (the festival for mobile media art) took us for a school trip to the Instituto Cultural Inhotim. An hour drive away from Belo Horizonte, Inhotim is a contemporary art museum, made of pavilions and installations spread over a lush botanical garden.

By garden i mean 600 hectares of natural reserve and a Tropical Park, with 45 hectares of gardens with botanical collections and five ornamental lakes, which together form an area of 3.5 hectares. Part of it was designed following the suggestions of landscape architect Roberto Burle Marx. The enormous variety of plants makes it one of the largest botanical collections in the world, with rare tropical species and a forest reserve which is part of the Atlantic Forest biome.

Simon Starling, ‘The Mahogany Pavillion’ (Mobile Architecture No.1), 2004

Simon Starling, ‘The Mahogany Pavillion’ (Mobile Architecture No.1), 2004

Since its opening in 2005, Inhotim has opened new pavilions to house permanent as well as temporary exhibitions and commissioned new site-specific projects to artists such as Doug Aitken, Matthew Barney, Victor Grippo, Chris Burden and Pipilotti Rist.

It is a breath-taking place. You walk around and think ‘Wow! If the Xanadu of art existed it would be this place. Or at least something disturbingly similar.’

There is some 350 works to discover. I’m not sure i managed to track down all of them but here’s a brief overview of my favourites:

Chris Burden, Samson, 1985, mixed media, photo: Eduardo Eckenfels

Chris Burden, Samson, 1985, mixed media, photo: Eduardo Eckenfels

Chris Burden‘s work is often reduced to the stunning performances in which he explored personal danger as artistic expression. For Shoot (1971), he had an assistant shoot a bullet in his left arm by an assistant from a distance of about five meters. Why stop there when you can do better? He set fire to himself, nailed himself on a car, had himself cut, starved, drowned, sequestered, etc.

Chris Burden, Samson, 1985, mixed media, photo: Eduardo Eckenfels

Chris Burden, Samson, 1985, mixed media, photo: Eduardo Eckenfels

The work on show at Inhotim, Samson, is of a different genre. It is potentially dangerous but not for the artist. The piece consists of a 100 ton jack connected to a gear box and a turnstile. The jack pushes two large timbers against the walls of the gallery. To enter the gallery, visitors must pass through the turnstile and each turn of the turnstile slightly expands the jack. If enough people visit the exhibition, Samson could, theoretically, destroy the building. The installation speaks volume of Burden’s opinion of museums and art institutions which the artist identified with “the establishment.” By forcing spectators to pass through the turnstile in order to satisfy their curiosity, Burden assigns them equal culpability in the potential destruction of the gallery space.

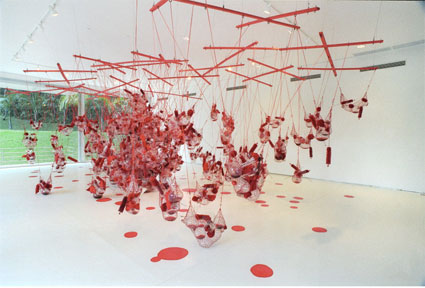

The True Rouge Gallery contains only one installation: True Rouge (1997) by Brazilian artist Tunga.

True Rouge Pavilion

True Rouge Pavilion

Tunga, True Rouge, 1997

Tunga, True Rouge, 1997

The work of Adriana Varejão has also been given its own beautiful pavilion, designed by architect Rodrigo Cerviño Lopez. Among the works exhibited, I particularly liked the Panacea phantastica (2003-2007). You don’t need to know that the tiles portrays 50 species of hallucinogenic plants from different parts of the world to be slightly troubled when you see it.

Adriana Varejão Gallery, photo: Bruno Magalhães

Adriana Varejão Gallery, photo: Bruno Magalhães

Adriana Varejão, Carnívoras, 2008, oil and plaster on canvas

Adriana Varejão, Carnívoras, 2008, oil and plaster on canvas

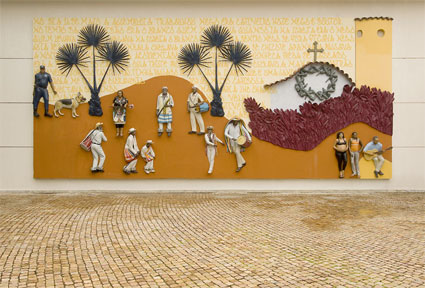

John Ahearn’s murals are often the outcome of a long immersion by the artist and his frequent collaborator, Rigoberto Torres, into a community. They spend time observing its people, their character, values, and vitality in order, in order to better portray everyday people, who rarely have a say in how they are portrayed.

John Ahearn e Rigoberto Torres, Rodoviária de Brumadinho [The Bus Station of Brumadinho] (2005)

John Ahearn e Rigoberto Torres, Rodoviária de Brumadinho [The Bus Station of Brumadinho] (2005)

The protagonists of Inhotim’s murals are the people living in Inhotim’s surrounding region of Brumadinho. A first mural, Rodoviária de Brumadinho [The Bus Station of Brumadinho] (2005), depicts the bus station of Brumadinho and the people who move through it, a place that is not only a center of transport but of social life as well, as it is also home to popular dances.

John Ahearn e Rigoberto Torres, Abre a Porta, 2006, automotive paint on fibre glass, 530 x 1500 X 20 cm, photo: Eduardo Eckenfels

John Ahearn e Rigoberto Torres, Abre a Porta, 2006, automotive paint on fibre glass, 530 x 1500 X 20 cm, photo: Eduardo Eckenfels

The other mural, Abre a Porta [Open the Door] (2006), depicts a solemn and spirited religious procession that takes place every year at the church just behind this mural and uphill from it, that is enacted by the Congado and Moçambique, two branches of a local population of pure African lineage descended from slaves who practice a kind of Catholicism that has absorbed animistic deities.

And of course any collection of contemporary art has its Olafur Eliasson. There’s actually more than one at Inhotim. The one i found most engaging is the Viewing Machine.

Olafur Eliasson, Viewing machine, 2001-2008, stainless steel, photo: Pedro Motta

Olafur Eliasson, Viewing machine, 2001-2008, stainless steel, photo: Pedro Motta

Looking like a grown-up and luxury version of the kaleidoscope gadgets for kids, the work creates an effect of reflected light with six mirrors forming a hexagonal tube. Visitor can maneuver the machine toward any point of interest. Through superimposed reflections, a myriad of forms is exposed.

More images in my flickr set.