According to the World Bank‘s latest estimates, the world generates (and often poorly manages) 2.01 billion tonnes of municipal solid waste annually, 12 percent of it being plastic. A third of that plastic finds its way into fragile ecosystems such as the world’s oceans.

Plastic debris now aggregates in gigantic floating landfills in oceans and endangers wildlife. Turtles ingest plastic bags and balloons, tiny fragments carpet the sea bed while chemical additives used in plastics even ends up in birds’ eggs in High Arctic. We’ve all read about this kind of stories, just as we’ve heard about the small gestures we should adopt to curb plastic waste. Yet, the growth of the plastic tide looks unstoppable.

Swaantje Güntzel, Hotel Pool, Intervention, 2016. Photo by Jan Philip Scheibe

Scheibe & Güntzel, PLASTISPHERE Portrait. Photo by Scheibe & Güntzel

Swaantje Güntzel, an artist with a background in Anthropology, has long been investigating our conflicted relationship with waste. Her work forces us to confront the dramatic consequences that trash pollution is having all over the world, from our city streets to the wildlife living at the other end of the world. Using aesthetics, provocation and humour, she lays bare the interdependence between our daily consumer choices, tepid reactions to environmental urgencies and fragile ecosystems.

Her strategies to spur us into action are many. She exhibits porcelains, photos, embroideries and sculptures inside galleries of course. But she also goes into the streets and infuriates passersby with her public performances. Some of her interventions involve the conspicuous “relocation” in touristic areas and fjords of trash dumped by absent-minded citizens. Others see her placing underneath public park benches sound devices playing a series of sounds generated by humans underwater, the kind of noises we never talk about but that nevertheless deeply disturbs wildlife swimming and living in the North and Baltic Sea, Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean.

Swaantje Güntzel, Offshore (detail), 2015, sound intervention, Aabenraa ARTweek, Denmark, Rosegarden. Photo by Jan Philip Scheibe

Swaantje Güntzel, LOOPS LH 150 E, intervention excavator 1 2018. Photo by Jan Philip Scheibe

Many of her works involve collaborations. Often with artist Jan Philip Scheibe but also with activists, researchers or even employees in a recycling plant. She lent some of her ideas and talent to environmental organizations such as Ocean Now in order to create campaigns that show her own face (and even, in the last iteration of the campaign, the faces of famous German public figures) covered in microplastics collected on beaches across the world. She also regularly collaborates with scientists in order to ground her artworks in robust facts or get help gathering plastic toys trapped inside the digestive system of sea birds. Last year, she even spent a couple of weeks on a huge scrapyard near Stuttgart to understand the whole process that keeps raw materials inside a closed recycling loop.

Ocean Now is currently using Swaantje Güntzel’s artwork “Microplastics II” for its In Your Face project, part of their campaign “Microplastics in Cosmetics and Cleaning Products”. Photo by Helen Schroeter

Swaantje Güntzel, MIKROPLASTIK II, 2016. Photo: Henriette Pogoda

I discovered her practice through the artworks series that explores the plastic invasion of our daily lives and oceans but our online discussions also brought us to discuss excavator choreographies on scrapyards and how to stay sane when the world around you is sinking under piles of garbage.

Swaantje Guntzel & Jan Philip Scheibe, PLASTISPHERE/Promenade Thessaloniki Performance, 17 March 2016, Thessaloniki, Greece. ARTECITYA – Envisioning the City of Tomorrow 2014-2018 / Goethe-Institut Thessaloniki & artbox.gr

Hi Swaantje! I was very moved by PLASTISPHERE/Promenade Thessaloniki, which you realised within the project ARTECITYA – Envisioning the City of Tomorrow 2014-2018, when I first read about it. It makes visible, in the most shocking way, how careless we are in our daily life when it comes to plastic trash, even when we are in the proximity of the sea or of a park. And even though we’re all aware of the problem by now. How did passersby react to your gestures of throwing plastic back into the urban environment? Did they get angry at you?

What you see in the video is not the whole truth because it was impossible to cover every reaction. In performance art you have to decide whether you focus on the performance or on the documentation because as soon as people see there’s someone filming or taking pictures around, they immediately think this is not serious and will refrain from intervening. We thus had to ask the filmmaker to stay away and try to be invisible as much as he could. Several moments in the performance were even stronger than the ones you can see in the video. For example, when we started the performance, after some 10 meters as I had just begun to throw out the garbage, a guy on a bike stopped and spat at me. His spit was all over my dress. He didn’t even ask what was going on. Further on, we had people yelling and shouting at us. The old woman in the video wasn’t just slapping me, she was hitting me hard. And she wasn’t the only one. There’s also this guy at the end of the video whom we later discovered was part of far right group The Golden Dawn. If it hadn’t been for the curator who was running behind and trying to explain what we were doing, I think he would have beaten us up.

Scheibe & Güntzel, PLASTISPHERE Promenade, 2016, Thessaloniki. Photo by Giorgos Kogias

Collecting garbage at Galerius Palace Thessaloniki, 2016. Photo by Giorgos Kogias

Did people get angry like this everywhere you presented the performance?

Yes, people react that way pretty much everywhere we go.

Lately, I’ve been wondering why people get so worked up. They don’t get angry when they see people dropping garbage or when they see trash in the street. They only get so worked up when they see somebody doing it in such a condensed and obvious way. I find it a bit hypocritical.

The funny thing is that I’m only relocating that garbage. We always start by picking up the trash we find laying around the city. In the case of Thessaloniki, we picked it up at a nearby archaeological site. The site is inside the pedestrian area. You can get a ticket, enter and visit the site. Yet, people who walk by still throw their wrappings onto the archaeological site.

In the first performance, I was relocating the actual garbage within the site, picking it up in one place and throwing it in another. After that, we took that garbage and moved it three blocks away, on the promenade. Only this time, we were throwing the garbage while riding some kind of bike for tourists.

I think that the outraged reaction has a lot to do with the fact that people don’t like to be confronted with garbage so blatantly. In a way, they know it’s theirs and it’s their responsibility. No matter where you are and who you ask, people seem to believe that garbage in public space is not their fault, that it’s the others who are to blame for its presence.

Public space is a collective space. We should all be responsible for it. Unfortunately, people just don’t want to take responsibility, neither in a personal sense nor in a collective sense. A performance in which we bring the garbage back to them is like a knock on their doors.

On a more abstract level, it has a lot to do with the walls we create around consumerism and in a broader sense around capitalism. When you start to talk about waste and plastic pollution, you have to question your way of life, the whole system of capitalism as well as us, humans. Of course, that’s probably not what is crossing these people’s mind immediately but I think it all comes together to create this strong reaction. And then on a more personal level, I think that a lot of people might be compensating for their daily lack of responsibility towards waste by acting in such a strong way and pretending they care. Because I throw garbage around in such an outrageous way, they suddenly take the role of the “clean up police”. It’s a bit like when you interview passersby on animal well-being, everyone will tell you that of course they’d be ready to pay a bit more if they were sure animals are treated better. The choices they make in their daily life, however, do not necessarily reflect what they say when they are interviewed in public. My work highlights this contradiction between what you do or say in public and what your private behaviour might be.

Scheibe & Güntzel, PLASTISPHERE Galerius Palace Thessaloniki, 2016. Photo by Giorgos Kogias

Do you think part of people’s anger can be explained by the fact that you look like a tourist on that touristic vehicle?

I don’t think so. I was acting in such an exaggerated way, throwing garbage around in broad daylight, in a popular area of the city and dressed in such an extravagant way. It was impossible to take me seriously. It was all staged to look like a performance or maybe an activist action to raise awareness around the waste problem.

Swaantje Güntzel, Portrait at Kaatsch. Photo by Jan Philip Scheibe

Last year you collaborated with the German recycling company Schrott- und Metallhandel M. Kaatsch GmbH in Plochingen as part of the Art Festival DREHMOMENT of KulturRegion Stuttgart in order to follow the route taken by the recycled objects, looking in particular at “the physical and logistical effort required to keep raw materials in a closed cycle of recyclable materials.” I found it interesting that you seemed to have established some relationship with the people working in this recycling company. What role played the relationship you established with them? How long did you stay there by the way?

I produced the actual work in two weeks but the whole relationship started long before that, in January, when we had the first encounter. That’s when I was presented to the company and they had to decide whether or not they wanted to work with me. They were very afraid I would run around their company looking for problems in the way they work. On the one hand, their fear was understandable because so far I had only focused on the damages of consumerism and not on the solutions to it. It took them 3 months to think about it. And it took me a lunch and a lot of wine with the boss of the company to convince him to say yes to the collaboration. But the moment we started to work together, they were incredible. They opened every door for me, they let me do everything I had dreamt of.

The work with the excavator that you can see in the short movie was something I had dreamt of. I never thought they’d allowed me to do that because that would mean slowing down the work process, it would be complicated, require a lot of men power and they’d lose money. And yet, the moment I told them about my idea, they reacted very fast and made it happen.

During my research and over the course of these two weeks last summer when I tried to realise most of the works, I found it very easy to talk to everyone. Later in October, for the opening of the resulting show, I had a conversation with one of the people working there and I almost apologised for being this woman crawling everywhere on their working space, always in the way of the workers on this big scrapyard. But the worker said “No! Not at all! All the women who work here would never come on the scrapyard, they prefer to stay inside the offices but you looked so interested in our work, trying to understand, getting yourself dirty, etc. That was actually very flattering for us.” The people who are in charge of the place also understood the potential of this synergy between the artist and the company and how something completely new could emerge from it. I had warned them that I wanted total freedom, that they couldn’t interfere with the content (unless it was for technical reason) but we never had any situation of tension.

I saw the power of recycling our waste, of keeping the resources in this loop and not lose any of it. It’s the future. They always say that recycling is the 7th resource of the world. Recycling will become an essential resource. Without it, we’ll destroy the planet even sooner than expected.

For me it was a new experience. For once, everybody was so happy about my performances! Although in the end, I think that people getting angry and me being beaten up is part of the solution. It’s one of the puzzle pieces in trying to understand that we are on the wrong track.

Swaantje Güntzel, LOOPS LH 150 E, 2018. Photo by Tobias Hübel

One of the works in the LOOPS series intrigued me. The triptych titled LOOPS / LH 150 E. Did the excavator create these marks?

Yes, you can see the process in the video.

My concept was that I wanted to visualise how much power is in the logistics and in the physical effort you need to keep resources in recycling loops. While doing my research on the scrapyard, I saw the company´s excavators picking up what seemed to be big bundles of steel wires that look like balls of wool but weight tons. The excavators grab these bundles and use them to move the trash from one side to the other. When they’ve finished the work, they use the bundles to clean the spot where they were working. When you see 3 or 4 of these excavators doing it at the same time, it looks like a ballet or a choreography. You can also sense the power. You feel the soil moving and shaking, the air getting very hot and the loud noise. It’s like you’re in a parallel world. I wanted to visualize these movements so I asked if i could drip these bundles into red paint, put the three steel plates on the ground and thus capture these moments.

Swaantje Güntzel, LOOPS LH 150 E, setting the plates, 2018. Photo by Jan Philip Scheibe

Swaantje Güntzel, LOOPS LH 150 E, intervention excavator 1 2018. Photo by Jan Philip Scheibe

Swaantje Güntzel, LOOPS LH 150 E, steel wire 2, 2018. Photo by Jan Philip Scheibe

Swaantje Güntzel, LOOPS LH 150 E, steel wire 1, 2018. Photo by Jan Philip Scheibe

Swaantje Güntzel, LOOPS LH 150 E, intervention excavator 1 2018. Photo by Jan Philip Scheibe

Swaantje Güntzel, LOOPS LH 150 E, finished plates, 2018. Photo by Jan Philip Scheibe

You hold a Masters Degree in Anthropology. How does that background inform and influence your artistic practice?

At the beginning, I didn’t think it would influence my practice. I was actually hiding that fact. When I started studying art, I was already older than the others and I was struggling to find my spot. Especially because I was working on ecological topics that no one really likes. In the first years, I had a hard time defining myself. After 5 or 7 years however, I started to realise that the way I look at the world, the way I work, the way I observe is so linked to my studies in Anthropology that I couldn’t deny this background anymore and that it played a huge part in my artistic practice.

Besides, I have this project series with my boyfriend Jan Philip Scheibe, who is also an artists, where we try and analyse with the instruments from contemporary art how the interaction between people and their surrounding landscape is still visible and how this defined their culture and understanding of nature. How these people trying to be nourished by the surrounding landscape have interacted with it over the course of the past several hundred years. These projects require a lot of research and I’m the one in charge of that before we actually start the work. My technique, my way of researching are linked to that understanding of the world as an anthropologist.

When I work on plastic pollution, I collaborate with many scientists, with marine biologists, with physicians, experts in acoustics, etc. Without this academic background, I would have hesitated a lot before before approaching them and asking them if they were open to collaborating with me.

Swaantje Güntzel, Stomach Contents, 2010. Photo: Swaantje Güntzel

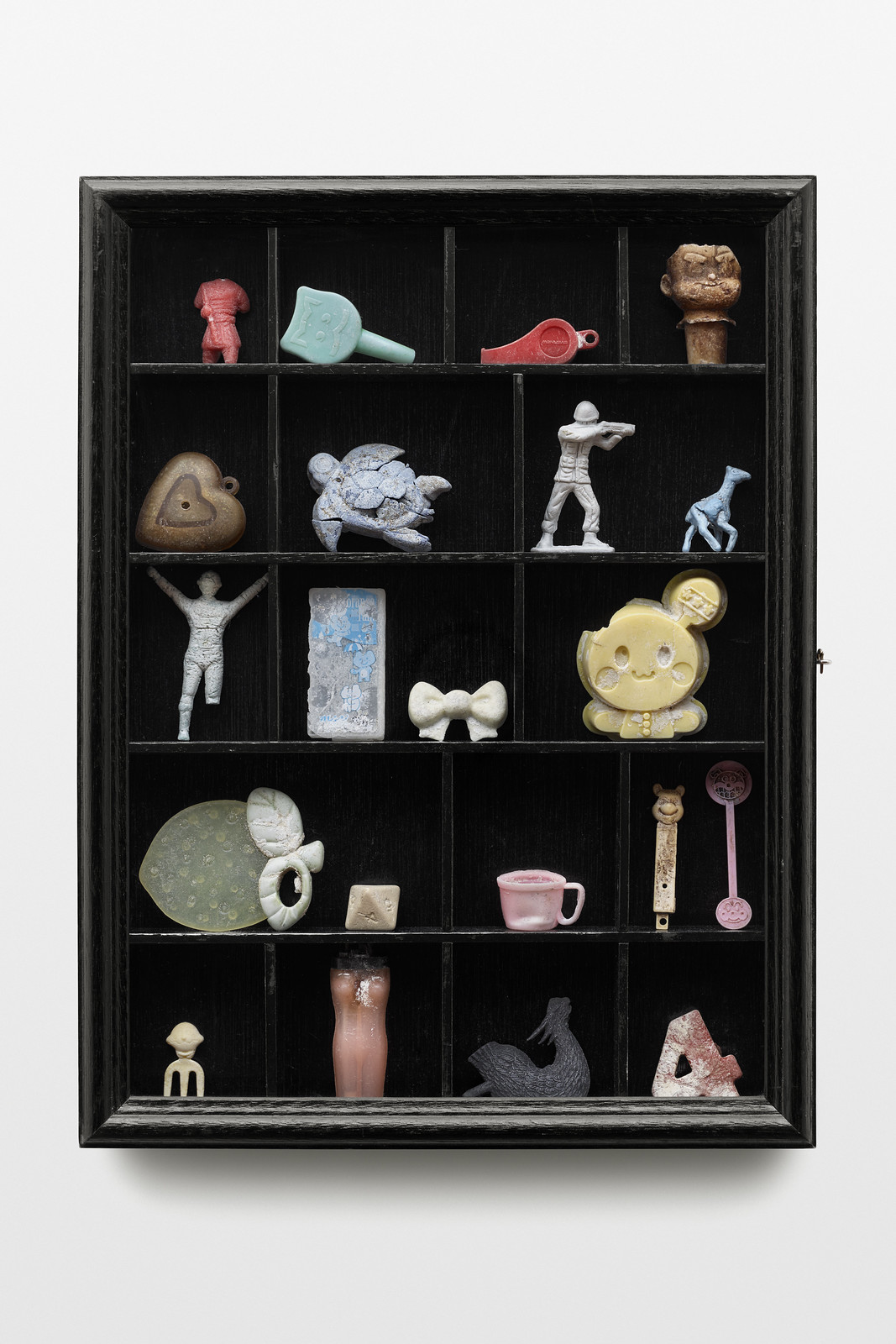

Swaantje Güntzel, Box Set XL, 2018, plastics, wood, glass, 41,3 x 31,5 cm. Photo Tobias Hübel

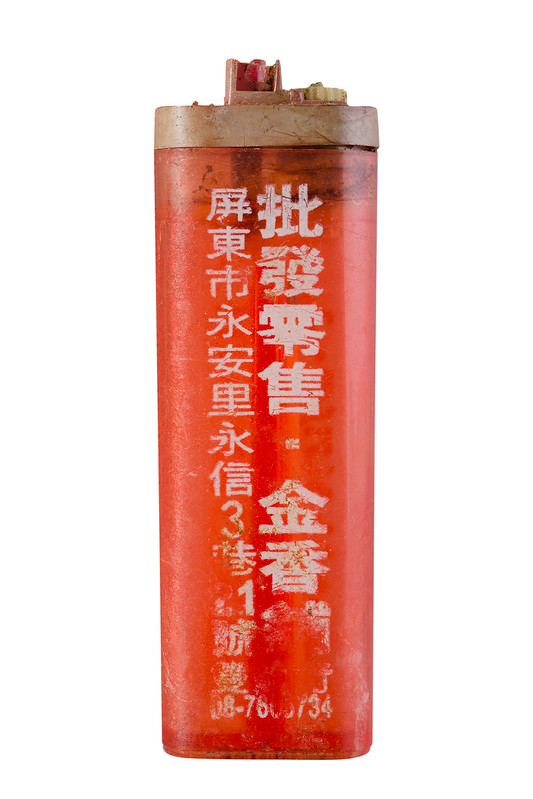

Swaantje Güntzel, Cigarette lighter R, 2014. Photo by Anne Sundermann

How did you work with these other scientists? Do they play only a consulting role or a more active one?

It depends very much on the project. For example, I worked with marine biologist Dr. Cynthia Vanderlip on a series of projects in which she played an active role. She is the head of Kure Atoll Conservancy, a seabird sanctuary in the Pacific Ocean. She was one of the first scientists I approached in my artistic career because I needed items that had been swallowed by birds in the ocean. She works a lot with Laysan albatrosses that have ingested plastic objects and she agreed in 2009 to provide me with all the materials I needed. She collects the pieces found inside dead birds on that remote Atoll. Now she can’t go to the Atoll anymore but she still directs the team over there and asks them to keep on collecting the objects for me. She answers any question I might have. Her role is thus very active.

With other scientists, it’s more about getting answers to very specific questions.

Last year was the first time I dared to present my work in a scientific conference on microplastics. I had no idea if they would appreciate this kind of presentation or even if it made sense for them to see how artists are working on this topic. From the interested reactions I got after the presentation, it looks like it was the right thing to do.

You’ve worked on the topic of plastic pollution for many years now. How do you see the discussions evolving? It seems to me that on the one hand, awareness has been raised years ago. On the other hand, we’re not making much progress in controlling plastic waste, are we?

I started to work on that topic in a time when nobody really knew about plastic pollution or about the Great Pacific Garbage Patch at all in Germany. There were a few scientists in the States who had just named the problem but there was nothing in terms in public awareness. I was so naive at the time. I thought that if I started making the problem visible, an understanding would grow and that over time we would take action. However, I could see that time was passing and that my work kept being labelled in curatorial texts or critical reviews as “raising awareness”. Last year, I started wondering how long we’d need to “raise awareness” before we decide to actually do something. Five years ago or so, people who are in charge started to advise the public on how we could change habits, use as little plastic as possible or put pressure on politicians and on the industry to see changes emerge. But we’ve been stuck in this same movement for such a long time. By now, I think that each of us is aware of the problem and we all agree that plastic doesn’t belong in the environment. And yet, not much has changed.

At the opening of my exhibitions, people view me as a kind of priest and confess their plastic sins to me. They would tell me that they understand the importance of my work, that it’s essential that someone makes the effort but then they’d try and explain me why they can’t make an effort themselves: it takes too much time and too much energy, it’s the industry that should act, people at the other end of the world do worse anyway, etc. Classic whataboutism that doesn’t help us move forward.

It’s the same with climate change, we know we have to do something and yet we stand there. We prefer to blame others, keep our heads in the sand and prolong our way of life.

Swaantje Güntzel, Blowback II, 2015, Aabenraa ARTweek, Denmark, Photo by HC Gabelgaard

What keeps you motivated and sane? because sometimes when I read how turtles choke on plastic, how microplastics ends up in the food chain and more generally how biodiversity is dying and the climate is warming up, I despair and want to forget about all that.

You have to look at my biography to answer that one. I grew up in the 70s and 80s, a time characterised by what some like to call “eco-pessimism”. As a kid, I was traumatised by what we were doing to this planet. I was a little girl asking adults “Now that you know what we did to the environment, why don’t you change your behaviour?” And I would always get an answer which meaning can be summed up in: “As adults we screwed it up. Now it’s on you to find a solution and save the world.” I was old enough to take their words seriously and I was depressed about the challenge I had to face: saving the world pretty much on my own.

Today’s young people feel the same but at least they have social media to connect and combine their energy and knowledge and turn it into something as powerful as the Fridays for Future movement. Back then however, it wasn’t the case and it’s only recently that I discovered that many people my age had experienced the same depression and sense of helplessness. We did what we could of course. For example, going from door to door asking people to sign petitions against seal slaughtering or collecting money for the local pet shelter. But we felt alone and under so much pressure. At some point, I decided I would leave aside those topics for a while. I went abroad and studied anthropology. Over time however, I realised that both the environmental issues and art were so deep inside of me that I couldn´t ignore it anymore. I decided that art could help me put up with the pressure and feel like I was doing something. It’s not on the level of activism where you have to dedicate your energy to a cause every day, you have to fight and you live with the constant frustration.

Art would allow me to do something but it wouldn’t consume me as much. It’s the only way I found to deal with this global insanity without completely losing it myself.

Thanks Swaantje!

Eric D. Clark, Music producer, DJ. A collaboration between Ocean Now and Swaantje Güntzel’s artwork “Microplastics II” for the In Your Face project, part of Ocean Now campaign “Microplastics in Cosmetics and Cleaning Products” Photo: Saskia Uppenkamp

Swaantje Güntzel has a few exhibitions coming up: she’ll be participating to the Deep Sea group show opening at Ystads Konstmuseum, Sweden, on 1 June 2019. This Summer her work is part of the touring exhibition Examples to follow! Expeditions in aesthetics and sustainability in Erfurt, Germany. She is also preparing, together with Jan Philip Scheibe the work Preserved/Grünkohl opening at DA Kloster Gravenhorst, Germany on 12 July 2019. And of course, her collaboration with Ocean Now is currently taking the streets of Berlin to inform passersby about the urgent need to ban microplastics in cosmetics and cleaning products.