Globally, around 26% of the population do not have safe drinking water and 46% lack access to safely managed sanitation. Forced displacement nearly doubled during the last decade. In the EU, concentrations of fine particulate matter in the air have been consistently higher by around one-third in the poorest regions compared to the wealthiest ones. The world’s top 1% own more wealth than 95% of humanity. By 2050, nearly 70% of the global population will live in cities. The world’s wealthiest 10% caused two thirds of global warming since 1990. Oh! And i have no number to throw at you for this one, but slum tourism is a thing.

How can architecture and design address any of those inequalities?

The Republic of Longevity. Photo Delfino Sisto Legnani – DSL Studio

A Journey Into Biodiversity. Eight Forays on Planet Earth. Photo: Alessandro Saletta and Agnese Bedini – DSL Studio

Abdel Kareem Hana, Iftar in Rafah, 1 March 2025. On the first day of Ramadan, during the brief ceasefire in Gaza, Malak Fadda, a young activist working with other young people to provide assistance to the displaced, organised a community meal to “bring joy back to this street” and “share the pain”. Two weeks later, Israeli troops resumed their terrorist ground operations in Rafah. Photo by Abdel Kareem Hana

This year, the Triennale di Milano is looking for possible answers to the question above, examining the global issue of inequality through an impressive inquiry encompassing architecture, design, technology, bioscience and data.

Albeit very ambitious, the Inequalities international exhibition doesn’t offer definitive answers. Instead, it attempts to understand how the deep fractures of the present are created, explore their consequences and propose new ways to turn these fractures into perhaps opportunities for connection and healing.

I completely underestimated the size of the triennial. I thought one afternoon would have been enough to visit all the exhibitions in the programme and indeed it was possible but it was a hasty, frustrating and too superficial experience. I’d recommend two days if you are planning to visit Inequalities. Here are a couple of works and ideas i found particularly striking:

Filippo Teoldi and Midori Hasuike, 471 Days. Photo: Alessandro Saletta and Agnese Bedini – DSL Studio

The installation on the main stairs of the Triennale is a hard-hitting introduction to the theme of inequality. 471 Days is dedicated to those killed in Gaza from 7 October 2023 until the temporary ceasefire on 19 January 2025. I found the dataviz hard to read. The length of red ribbons corresponds to the number of deaths each day. On the steps, under each ribbon, a small plaque breaks the death count down between the 1,600 Israeli deaths and 46,900 Palestinian deaths. It looks like a cool, objective kill count. However, the disparity in the numbers, which has only grown since 19 January 2025, demonstrates that this is not a war. This is ethnic cleansing of Palestinians perpetrated by the wealthy, sophisticated and US (and EU)-backed Israeli army. The rich literally grinding the poor to a pulp.

We the Bacteria. Installation view at Triennale di Milano. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani – DSL Studio

We the Bacteria. Installation view at Triennale di Milano. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani – DSL Studio

Laura Kurgan, Dan Miller and Adam Vosburgh, Two Sides of the Same Coin. We the Bacteria. Installation view at Triennale di Milano. Photo: Alessandro Saletta e Agnese Bedini – DSL Studio

Inequalities are not just political, economic and social; they are also biological. Contemporary urban populations have 50% less bacterial diversity compared to their ancestors. The loss of potentially helpful bacteria affects our immune, metabolic and nervous systems. Today the microbiota is a reliable indicator of social and economic inequities. It is robust in those who have access to a varied diet and a healthy environment, but far less healthy in those who cannot afford any of that.

We the Bacteria. Notes Toward Biotic Architecture, curated by Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley, investigates how microbial ecosystems relate to spatial design and health inequality.

The show starts with our fear of “germs” before moving to a series of installations that details how we might benefit from including bacteria on the response to the challenges encountered in the fields of health (including mental health), the environment, architecture and infrastructure.

In her brilliant book X-Ray Architecture, Colomina argued that the modernisation of early 20th Century architecture was a response to illness. Society, traumatised by the spread of tuberculosis, was obsessed with fresh air, sunlight, physical exercise and hygiene.

These concerns were reflected in new techniques, materials, experiments and architectural innovations. Buildings were equipped with large windows and terraces to promote ventilation and direct contact with the sun. Surfaces were smooth, white and clean. Ornaments were absent. Wealthier households could even get domestic gym rooms for exercising. The sanatorium was the iconic example of germ-adverse architecture. Alvar Aalto conceived the Paimio Sanatorium as a “medical instrument”. Each floor of the building had sunning balconies, where weak patients could be pulled out in their beds.

Spitting sink (between the two sinks) from a patient room in Paimio Sanatorium. Aino and Alvar Aalto. Photo: Alvar Aalto Foundation

The exhibition features an original spitting sink from a patient room in Paimio Sanatorium.

In 1946, the development of the antibiotic streptomycin finally offered an effective treatment for TB. However, since the 1980s, antibiotic resistance has become a growing problem, with increasing rates of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Over the years, overuse of antibiotics in humans and other animals has made infections harder to treat and other treatments riskier.

Today, society is finally realising that bacteria are not the enemy. Neither in the body nor in architecture.

Colomina and Wigley argue that architecture should work in close alliance with bacteria. Some can be used to create new, more sustainable materials, building practices and methods of renovation (like the bacteria used to clean monuments.) They also call for an architecture more in tune with our intestines. Instead of building fortresses that insulate us from the elements, animals, insects and bacteria, architecture should make room for the bacterial community that already coexists within us.

Several installations in the show illustrate the growing importance that bacteria could take in architecture and urban planning. I’ve selected 2 of them:

Philippe Rahm Architectes, Microbial Migration

The climate in Milan has been warming for several years now. Under a high-emissions scenario, temperature increase might even reach +5° Celsius by 2100, resulting in a profound transformation of ecosystems. Faced with the rising temperature of their natural habitat, many plants, animals, but also bacteria and viruses, will relocate ever further north in Europe.

Inspired by assisted migration programmes (nature conservation tactics wherein plants or animals are intentionally moved to geographic locations better suited to their habitat needs and climate tolerances), Philippe Rahm Architectes propose to extend this translocation to the microbiome. Thirty years from now, Milan’s climate will be similar to the one found today in Puglia, in southern Italy. The Microbial Migration project offers to bring soil from organic farms in Puglia in Southern Italy to Milan. This soil will come with the microbes that today’s children in Milan will encounter as adults. By incorporating Puglia soil into Milan playgrounds, the kids will acquire the microbiome capable of responding to tomorrow’s infections.

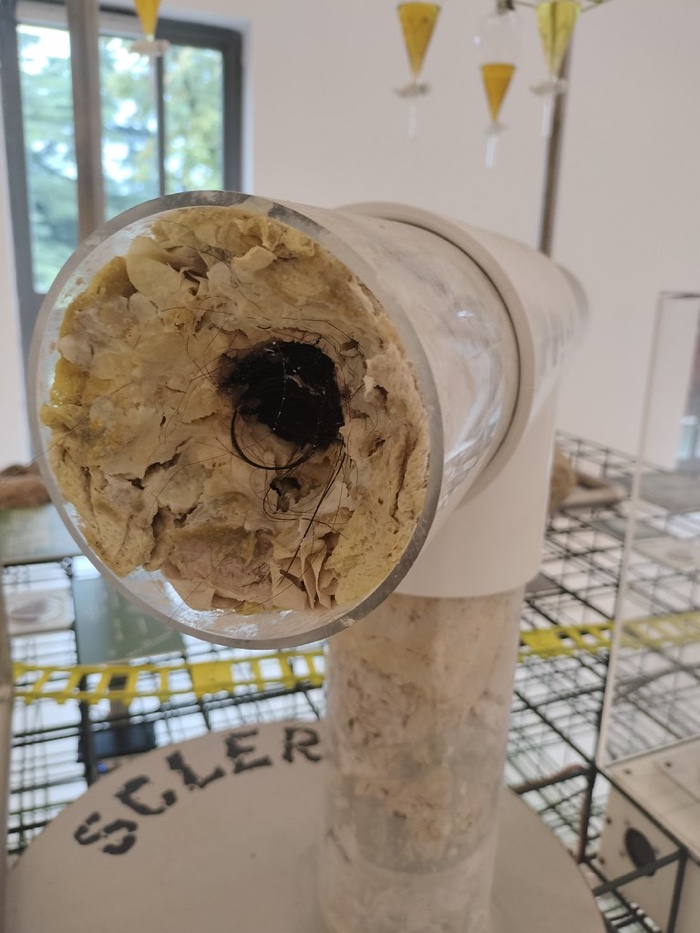

There are other proposals by prestigious design and architecture studios, but the one that truly fascinated me is an installation detailing all the gross materials that end up in drains and sewage, where they become part of fatbergs. I looked around the exhibition room but couldn’t find who made that installation.

Workers in protective suits conduct a cleanup operation to clear petroleum-based “tar balls” washed ashore on Coogee Beach in Sydney. Photo: AFP via Getty Images

‘Total monster’: fatberg blocks London sewage system. Photo: Thames Water

The installation designers created a kind of taxonomy of fatbergs. The names given depend on the shape, behaviour and content of the fatbergs. What these masses of waste matter have in common, however, is bacteria and FOG: the fat, oil and grease that we casually throw down the drains of our homes and that accumulate and coalesce into gruesome blobs. Here are three types of fatbergs:

Discovered in September 2017 under the Whitechapel area of London, the CONCRETE MONSTER was an assemblage of non-degradable wet wipes, cooking oil, sanitary products and other materials flushed down toilets or tipped down drains. They congealed together and formed a dense mass that resisted pickaxes. The CONCRETE MONSTER is a mirror of our diets, consumerism and infrastructural neglect.

AVALANCHE was a fatberg discovered in Liverpool in 2019. It started with FOG that cooled down and solidified on the inner surfaces of the sewer walls. The greasy deposits trapped materials that were not meant to be thrown down the drain. It grew into a heavy lump until a massive section of the fatberg dislodged and slid or collapsed downward through the sewer system like an avalanche, scraping off more sludge and debris as it went. When it was discovered in 2019, the fatberg had been eaten from the inside out by fat-loving bacteria. Over time, the core of the fatberg became hollow and mushy, while the outer shell was hard and crusty.

One last fatberg! The GYRE started its life with FOG entering the rivers and storm drains that flow into the ocean. Along the way, it picked up dental floss, cotton swabs, hair, faeces and other floating debris. In the cooler ocean temperatures, the mass congealed into lumps, bacteria and microbes may even help bind it, starting a slow, accumulating process. Constant motion grinds the mixture together and, over time, it hardens into tar-like blobs. Some of these mini fatbergs stayed afloat, while others sank and washed ashore. On 24 October 2024, mysterious black spheres washed up on Sydney beaches. They contained human faeces, methamphetamine, human hair, fatty acids and food waste. And they are back!

Marina Otero Verzier, Computational Compost. Cities. Exhibition view. Photo: Delfino Sisto Legnani – DSL Studio

Marina Otero Verzier, Computational Compost

Elsewhere in the triennale, Marina Otero Verzier is showing Computational Compost, a prototype and film exploring the environmental impact of data storage. The prototype repurposes the heat generated from computational simulations of the universe’s origins to power a vermicomposting machine. Live worms and microorganisms thrive on this energy, transforming organic matter into fertile soil and establishing a connection between digital infrastructures and ecological cycles that help us imagine a less extractive future for digital infrastructure.

There’s something poetic in computers trying to understand the origin of the universe (and of our life) while generating compost, which is also at the origin of life.

The triennial also includes international ‘pavilions’.

Giovanni Hänninen, Towards Gratosoglio, Villaggio delle Rose, Italy. Roma pavilion at Triennale Milano

Giovanni Hänninen, Builder Italian Roma, Villaggio delle Rose, Italy. Roma pavilion at Triennale Milano

Giovanni Hänninen, Always prepared, Villaggio delle Rose, Italy. Roma pavilion at Triennale Milano

The Roma & Sinti pavilion gave a chance to one of the most overlooked and misunderstood communities in Europe to express themselves over their idea of home and the question of housing in a context of of marginalisation. The presence of the pavilion gives visitors a precious opportunity to learn about the Roma and the Sinti, people who are, in the vast majority of the cases, caricatured by the media and used by the most loathsome politicians as bogeymen and opportunities to present themselves as the “tough” face of Law & Order. of marginalisation.

Giovanni Hänninen is showing his documentation of the daily life and atmosphere in the Villaggio delle Rose (Village of the Roses), a community outside of Milan where 240 people, including 100 children, live. Legally. Unfortunately, the Municipality of Milan is planning to destroy their homes and break up a close-knit community. The Villaggio delle Rose is not just a group of houses; it is also a place of historical memory and culture for these descendants of partisans and deportees who often find themselves alone in their ceremonies to remember Porrajmos, the Holocaust of Roma and Sinti people.

Béla Varadi, Family, Ciganhegy, Hungary

Béla Varadi, Sister Mother, Ciganhegy, Hungary

Béla Varadi, Father, Ciganhegy, Hungary

Béla Varadi, Graveyard, Ciganhegy, Hungary

Roma & Sinti Pavilion. Photo: Alessandro Saletta and Agnese Bedini – DSL Studio

In the Gypsy Hill series, Béla Varadi shows the impact that systematic politics of discrimination has on Roma people in Hungary: The socialist Hungarian state wanted to eliminate the so-called ‘gypsy problem’. Dismantling the separated gypsy settlements was one way to achieve that goal. That was how the gypsy settlement in my village moved from the visible top of the hill to the invisible valley.

DIVERSE AGING project by Tsinghua University: from Internet

The pavilion of China was overwhelming. Way too much content crammed into one room, but I did love how it drew on traditional Chinese philosophy to frame imbalance as an opportunity to address inequalities. One section of the exhibition looked at hacks designed by elderly people to make their lives more comfortable. The two-person electric wheelchair is particularly charming: some elderly people attach a small cart to the back of their wheelchair so it that can carry another person standing. While one person operates the electric wheelchair to move, their companion can travel with them.

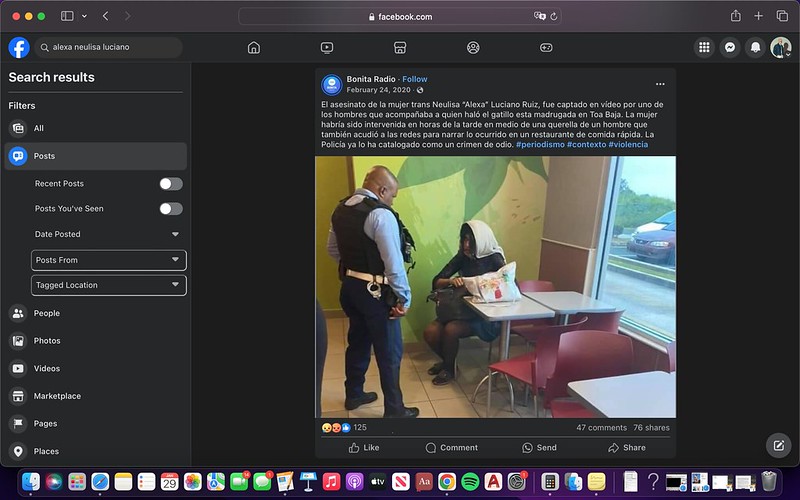

Facebook post showing the image that went viral and the discourse that ensued

Puerto Rico Pavilion, “Once Upon Three Feminicides”. Installation view at Triennale di Milano

The Puerto Rico Pavilion is dedicated to the memory of Neulisa Luciano Ruiz, also known as Alexa, a Black, homeless, transgender woman murdered in 2020. She appeared to have been targeted by her killers after a photo of her taken in a McDonald’s was uploaded to Facebook by someone who falsely claimed Alexa had been spying on children in the bathroom. The post went viral. She was killed near her tent shortly after.

The installation reconstructs the crime through 3 three interconnected sites: a McDonald’s bathroom stall, a roadside tent and the digital space of Facebook. Together, they act as a distant memorial where none exists in the physical spaces of her life. The work also reflects on the role architecture could play in advocating for the protection of marginalised communities.

The 24th International Exhibition Inequalities. Triennial of Milan is on view until 9 November 2025.