Vegetal Entwinements in Philosophy and Art, edited by curator Giovanni Aloi and philosopher Michael Marder. Published by MIT Press.

This reader contains essays by experts in ethnobotany, cultural theory, Native American studies, evolutionary ecology, anthropology, biological sciences, speculative fiction, environmental humanities, food sovereignty, etc. The texts look at plants but they also and mostly look at us, at our reluctance to acknowledge the value of plants radical alterity, at our urge to dominate and classify everything around us, at the role of art and philosophy in dismantling the cultural framework imposed by anthropocentrism. With this publication, Aloi and Marder lay out a “thinking-sensing framework” which objective is to help us appreciate the inscrutability of plants and redefine our relationship with the vegetal world, the land and ecosystems.

Marco Bay, Milanese Tropical Forest, 2017. Palms and bananas in front of the Duomo in Milan, 2017

Mileece Petre. Photo

Vegetal Entwinements in Philosophy and Art is a brilliant book. It is massive (656 pp), often provocative and the quality and diversity of the viewpoints included is remarkable.

Here’s a short selection of the essays that i found particularly eye-opening:

Monika Bakke uses the works of Natalia LL and Zofia Kulik as springboards to explore not only the non-normativity of plants’ many sexual strategies but also Western philosophy’s insistence on comparing men to animals and women to plants by virtue of their (perceived) respective characteristics of dynamism and rationality, on the one hand, and passivity, decorative qualities and lack of rationality, on the other.

Marc Quinn, Garden, 2000

Marc Quinn, Garden, 2000. Photo Attilio Maranzano / Fondazione Prada

In his superb essay about botanical colonisation, Giovanni Aloi explores the violence of gardening. He makes a call for a more considerate use of “decolonisation”, a term that “lends an ethical edge to scholars in a desperate need to reaffirm their relevance amid a fast-changing world besotted by online entertainment”. Decolonisation uses gardens as ideological islands inhabited by non-native species that Western colonisers imported and imposed on the territory. For some decolonialist discourses, the eradication of these plants is a necessary condition to restore “purity” (a concept which is in itself immensely problematic.)

By supporting the mistaken notion that Western colonisers were the only agents who had detrimental and transformative impacts on the ecosystems of this and other lands, these views obliterate the cultural and technical range of skills developed by Indigenous people to support their own civilisations.

“Decolonizing should not equate to dismantling or erasing, and living plants should not be seen as monuments to white supremacy either”, Aloi writes. “At this point, we need to focus on the nuances of representation and its entanglements with multiple historical and scientific milieus.”

Rashid Johnson, Antoine’s Organ, 2016. Installation view, Unlimited, Art Basel, Basel, 2018. © Rashid Johnson

When the literature on human dimensions of invasive species mentions indigenous nations across the U.S. and Canada, it tends to focus on their vulnerability to invasive species. In their paper, Nicholas J. Reo, Kyle Whyte, Darren Ranco, Jodi Brandt, Emily Blackmer and Braden Elliott demonstrate that, far from being passive victims of environmental changes, Indigenous natural resource managers and practitioners not only implement all of the generalised steps taken by settler governments and NGOs plus some unique, culturally informed strategies. The data collected by the researchers shows the necessity to directly involve these communities in developing environmental change policies.

Baracco+Wright Architects with artist Linda Tegg, Grasslands Repair, 2018. Photo by Rory Gardiner

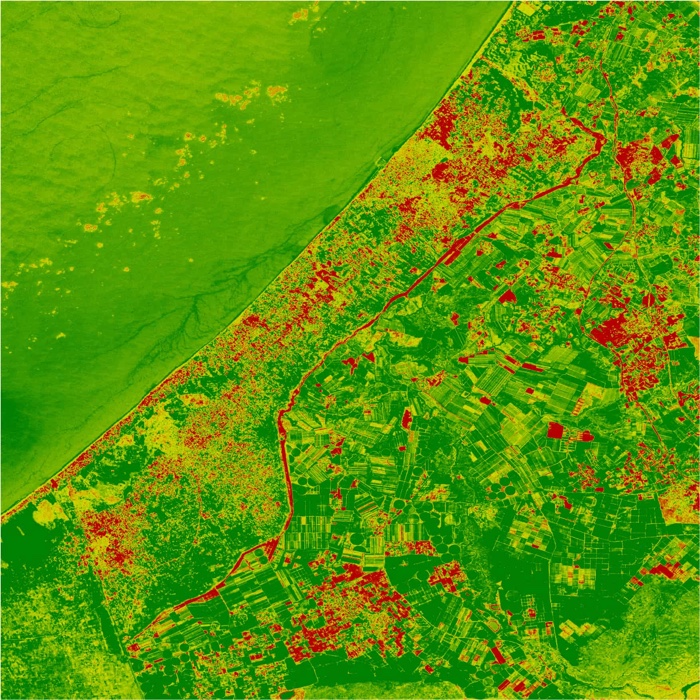

Centre for Contemporary Nature (CCN). Long-term changes to visual indicators of vegetation health across the Gaza region over the past three decades of Israeli occupation. Red indicates areas in which vegetation was completely eradicated. 2014-ongoing

My favourite chapters were the interviews with artists. Mark Dion, Zayaan Khan, Jonathon Keats, Spela Petrić, Diana Scherer, Linda Tegg and Baracco + Wright, Anicka Yi, Maria Thereza Alves, Uriel Orlow, D. Denenge Duyst-Akpem, Nathalie Anguezomo Mba Bikoro and others discuss their sources of inspiration, the methodologies they adopt when working with plants, what plants have taught them, the ethical or political considerations that inform their practices, the challenges encountered while working with plants, etc.

I was especially fascinated by the work of Samaneh Moafi, Centre for Contemporary Nature (CCN)—a research division of Forensic Architecture that investigates colonial, military and political forms of violence as they manifest in environmental destruction. Moafi describes one of the investigations the group launched on how Israel “weaponised” the wind to spray crop-killing herbicides over Palestinian farms located along the eastern border of Gaza.

Dan Choffnes writes about the medical traditions that developed across Africa, Australia and the Americas before the arrival of the Europeans. Plants were not only used to promote health and treat illness, they also played a crucial role in the development of world views and philosophies that link and individual’s wellness to the state of the universe.

Uriel Orlow, Theatrum Botanicum, 2015–2018

Uriel Orlow, Learning from Artemisia, 2019–2020

Maria Thereza Alves, Seeds of Change, 1999-ongoing

Maria Thereza Alves, To See The Forest Standing (video still), 2017

In another essay, Giovanni Aloi considers the conditions of vegetal death. Given the right conditions of humidity, heat and light, a plant can be splintered apart in multiple cuttings and yet continue to thrive, while even the fragment of roots, leaves or tendrils can in some species generate an individual plant. This radical alterity of plants can help overcome “plant blindness”, a cultural -mostly Western- condition that prevents us from recognising the complexity of plant life beyond the realm of curiosity or specialistic knowledge.

John Baldessari, Teaching A Plant The Alphabet, 1972

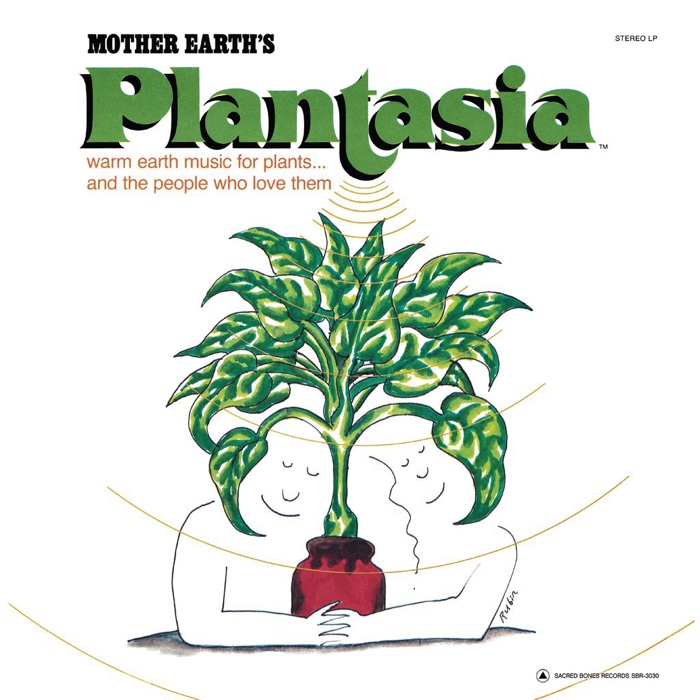

Mort Garson, Mother Earth’s Plantasia, 1976

Dan Milner, From Hell It Came, 1957

Teresa Castro discusses the plethora of articles, books, vinyl records, artworks and films on the subject of plant communication released in the 1970s. The success of the topic can be attributed to a mix of hippie counterculture’s love of nature, the flourishing of ecological thinking and the cybernetic paradigm that looked at plants as communication systems in themselves that respond chemically and electronically to the environment and other stimuli and that are able to learn and self-correct in response to feedback.

Michael Marder questions the anthropocentric assumption that to have a language is to be able to speak. Twenty-first-century plant sciences, he writes, navigates two contrasting ambitions: on the one hand, they prepare the ground for an acknowledgement that plants are endowed with language and intelligence (it’s no wonder that an essay by Stefano Mancuso and Alessandra Viola opens the reader), while, on the other hand, they make plants, as coherent living beings with their own modes of expression, disappear under the studies that break them down into minute molecular, atomic or subatomic components.

Angela Roothaan uses case studies illuminating the relations of human communities to trees, notably in West African traditions, to explore how these strengthen a shared understanding of the environment.

Charting the presence of weeds in culture from Antiquity to Giovanni Bellini’s St. Francis in Ecstasy and early herbariums, Allegra Pesenti, the curator of the exhibition A Weed Is a Plant Out of Place argues that weeds can be interpreted as visual metaphors for the (human) uprooted.

Marlene Atleo, a scholar and a member of the Nuučaańuł (Nuu-chah-nulth) community of Ahousaht, investigates the role of botanical and environmental knowledge in considering First Nations’ land rights.

Eduardo Viveiros de Castro looks at the criticisms of the Western distinction between nature and culture and questions the alternatives to this dualism, contrasting these proposals with the distinctions operating in Amerindian perspectivist cosmologies.

Mark Dion. Neukom Vivarium, 2006

Ethan Breckenridge, Plants Have No Back, 2008

Previously: Metaspore, a look into the “biopolitics of the senses”, Speculative Taxidermy. Natural History, Animal Surfaces, and Art in the Anthropocene, The Funambulist: Forest Struggles, Orchidelirium. Colonialism through the lens of botany, Palm oil, peatfires, Nutella and the anthropocene, Vegetation as a Political Agent, etc.