The Funambulist, a magazine and platform that engages with the politics of space and bodies, is one of my favourite publications. It is consistently interesting, pertinent and committed to giving a voice to viewpoints that tend to be ignored elsewhere. Yet, I haven’t written about the publication since 2017. It was time to bring up its brilliance again with a review of its current issue: Forest Struggles.

The 47th issue of The Funambulist is dedicated to both political struggles taking place in forests and political struggles in defence of the forests. The massive efforts of deforestation around the world, in particular along the equator (Peru, Brazil, Cameroon, Gabon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Indonesia, Malaysia, West Papua…), although specific to each context’s political climate, are the symptoms of a colonial and capitalist extractivism often connected with a suppression of Indigenous political struggle, or mere existence in their sylvan environment.

It’s 2023 and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva is wrestling with resistances to keep his campaign promise to reverse the damage done to the Amazon rainforest by Bolsonaro. It is absurd that the forest still needs to be championed and protected. I doubt anyone ignores the crucial role that they play in producing oxygen and cleaning the air, preserving biodiversity, storing carbon, helping fight soil erosion, providing medicine, etc. And in general acting as a decisive buffer against climate change. As this issue of The Funambulist demonstrates, the Amazon is not the only forest at risk. These ecosystems are at the centre of socio-political tensions in many parts of the world. What most of these forests have in common is that they are inhabited by indigenous communities who have accumulated a wealth of knowledge and experiences about the forests. Yet, their expertise and wisdom are hardly ever taken into consideration. Again, it is 2023 and, in spite of the decisive role they have played in finding the children lost in the Colombian Amazon (¡Guardia, Fuerza!) or in preserving biodiversity in the DRC or in Central Africa’s rainforest, we still haven’t learnt to trust their ancestral understanding of the land.

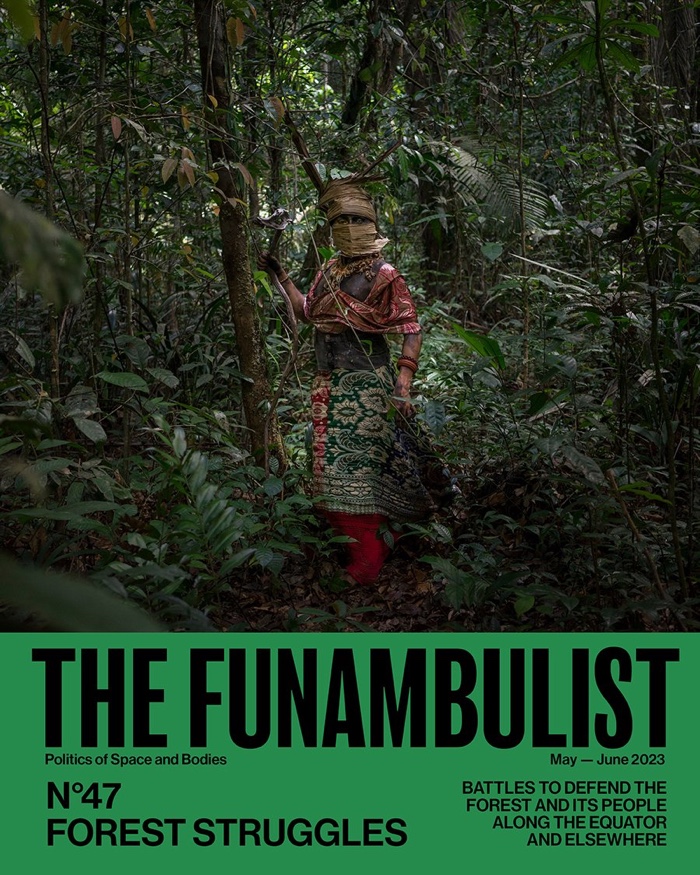

Romain Rampillon and Feda Wardak, Jusqu’où la forêt (still from the film), 2019

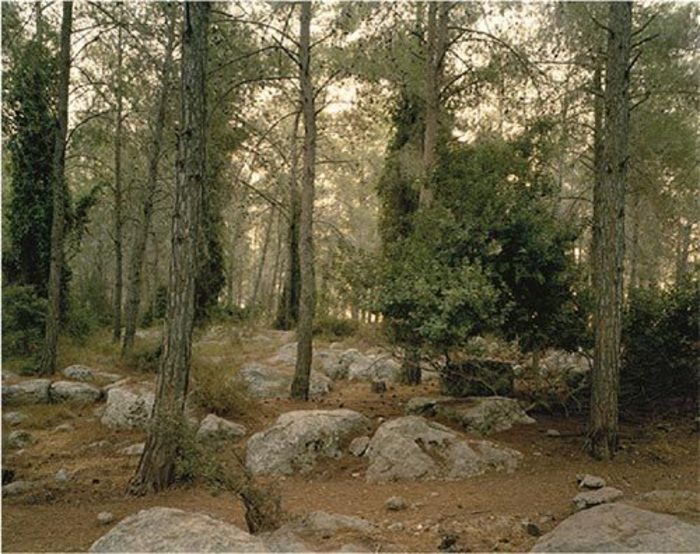

Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, The Saints Forest, 2005

Forests and their human and non-human inhabitants all over the world are the victims of human greed but they can also be casualties of what looks like noble ecological concerns but are in fact brazen operations of green colonialism. In his introduction to the magazine, Léopold Lambert gives two examples of green colonialism. First, Prospérité, an Indigenous village in colonized Guiana that is resisting the deforestation of their land to give space to a privately-owned solar panel power plant commissioned by the French authorities. The editor also reminds us about the forests planted on the ruins of Palestinian villages that had been forcedly evacuated and then demolished by Israel. The forest programme not only erases the traces of Palestinian history but it also provides the image of a modern country able to make the desert bloom. The forests often feature pine trees that are totally unsuitable for the local arid and hot environment.

The essays collected in the forest issue of The Funambulist document and comment on a series of political movements “occurring under the sylvan canopies.” If I have to highlight 3 of them, I would go for:

The fascinating essay written by Sophie Chao, an environmental anthropologist & environmental humanities scholar. Her text describes the struggle of the Marind People, who live in South Papua and who are confronted with the adverse environmental and social impacts of oil palm monocultures on their customary lands.

She describes how the Marind’s relationships of reciprocal care with non-human beings involve an acceptance that other forms of life, through their activities, may cause harm to other beings or come into friction with human interests. Their ethos also entails recognising that plants and animals are no less than humans victims of the violence of plantations. And that includes oil palm as the species suffers from being disciplined, oppressed and reduced to an industrialised commodity.

Even more interestingly, the Marind see in plants and animals allies in their struggles for justice. Native insects, reptiles, rodents and fungi, for example, act as parasites of the oil palm tree by repurposing the cash crop into a host and source of food.

Estado Novo propaganda poster: “The true meaning of Brazilianness is the march to the West”

Another highlight of the magazine is Léopold Lambert ‘sinterview with architect, researcher and writer Paulo Tavares. During the conversation, Tavares quotes Getúlio Vargas, president of Brazil, from 1930 to 1945 and from 1951 to 1954: “The Amazon will cease to be a simple chapter in the history of the earth, to become a chapter in the history of civilisation.” It is easy to see how this mindset still haunts the Brazilian rhetoric, and how much it is associated with ideas of progress, development and economic wealth. And not just in Brazil, alas!

While Tavares analyses how the Brazilian colonisation and extractive deforestation of the Amazon are carried out in the name of growth, he also examines the alliances between Indigenous, ecological and other grassroots political movements to defend the forest against colonial violence, using on-the-ground non-Western knowledge and remote sensing technologies as well as cartographic and architectural analyses. The result of Tavares’s collaboration with indigenous leaders and communities is a mapping of one of the largest Indigenous archaeological complexes. The research constitutes an unambiguous refutation of the colonialist claim that the Amazon is a territory without history or heritage

Air-spraying of glyphosate to destroy coca plantations has caused miscarriages, fetal abnormalities, and maternal deaths. Photo STR New (Reuters), via Quartz

Another essay I found particularly eye-opening is the one by artist, filmmaker and writer Hannah Meszaros Martin. Her text looks at the military use of glyphosate against various forests across the world. She turns in particular to the spraying of coca fields in the context of the “War on drugs” financed by the U.S. government and enacted by the Colombian army.

Decades earlier, during the war in Vietnam, the U.S. utilised aerial photographs of the forest before and after they had showered them with Agent Orange. The images were used as a demonstration that herbicides were a powerful weapon again counterinsurgency warfare. Very little thought was given to local ecosystems and communities. In fact, Meszaros Martin explains, the forests were not simply targeted because they allowed the enemies to hide, they were also conceptualised as the life source of rural resistance, which meant that the “rural” as a categorical entirety had to be eliminated. All human and nonhuman life considered to be subversive had to be eradicated.

Which, sadly, brings us full circle to what is happening in the Amazon rainforest and elsewhere today.

You can already pre-order The Funambulist 48 (July-August 2023) Fifty Shades of White(ness): Thinking Against the U.S.-centric Conception of Racialization.

Previously: The Funambulist Nº10: Architecture & Colonialism, Magazines to make you forget that we’ve just entered the Dark Age: The Funambulist, Neural and Gambiologos, The Funambulist magazine. Politics of Space and Bodies and Weaponized architecture.

Image on the homepage: A MATA SE-TE COME, by Uýra Sodoma. Photo: Lisa Hemes.