The Pentagon, Climate Change, and War. Charting the Rise and Fall of U.S. Military Emissions, by Neta C. Crawford, professor of international relations at Oxford University and co-director of the Costs of War Project at Brown University. Published by MIT Press.

The U.S. military is the largest institutional fossil fuel user in the world and thus the largest greenhouse gas emitter.

In her analysis of the Pentagon’s role in the greenhouse gas problem, Neta C. Crawford describes in detail how modern warfare, with its vast production of armaments and infrastructures, movements of heavy vehicles, aircraft and troops drives the demand not only for an enormous consumption of petroleum products but also for a U.S. foreign policy that guarantees constant access to fuel supply, notably in the Middle East.

The military, she explains, has long been aware of the threats that the climate emergency poses to its operation, to geo-political stability and to humanity in general. As early as in the 1950s and 1960s, the highest levels of the United States government—and the military in particular— were informed about the role of greenhouse gas emissions as a cause of potentially catastrophic climate disruptions. Policymakers, the author notes, have not yet responded with the same degree of urgency to the threat of global heating as they have acted to defend access to fossil fuels.

A petroleum supply specialist refuels a CH-47 Chinook at a hangar on Wheeler Army Airfield, Hawaii. Photo: Sgt. Sarah D. Sangster/U.S. Army, via

Environmental restoration employees deploy a containment boom at Offutt Air Force Base in Nebraska, as a precautionary for possible fuel leaks, March 18, 2019. Photo: Associated Press, via

While the Department of Defense has labelled the climate crisis a “threat multiplier” and seen first hands the effects that extreme heat and flooding are having on its operations, supply chains and infrastructures both across the U.S. and on foreign soil, it has so far not implemented convincing measures to reduce its carbon footprint. Not only has the U.S. military resisted including its emissions in the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, but it is also responding to the climate crisis by adapting to it rather than by diminishing greenhouse gases.

Following her analysis of the Pentagon’s fossil fuel addiction in detail, Crawford is looking at possible solutions to curtail U.S. military emissions significantly.

The political scientist believes that while the potential for climate catastrophes to spark climate wars is conceivable, further militarising the U.S. is not the wisest response to the problem. Militarisation raises the prospect of wasting resources or even potentially increasing the risk of war. Furthermore, the author argues that the climate crisis in itself will not inevitably lead to violence and war. She gives examples of countries that have solved difficulties in accessing resources not through conflict but by signing treaties of cooperation. Cooperation is cheaper and more effective than fighting after all.

Crawford calls for a shift from a mindset that conceives security based on military dominance to one that is based on human and ecological security. For her, reducing military emissions will require using nonmilitary tools—including economic sanctions- as well as breaking a deep cycle of economic growth, expansion, military mobilization and military-industrial production that is reliant on fossil fuels and further exacerbating competition with foreign powers.

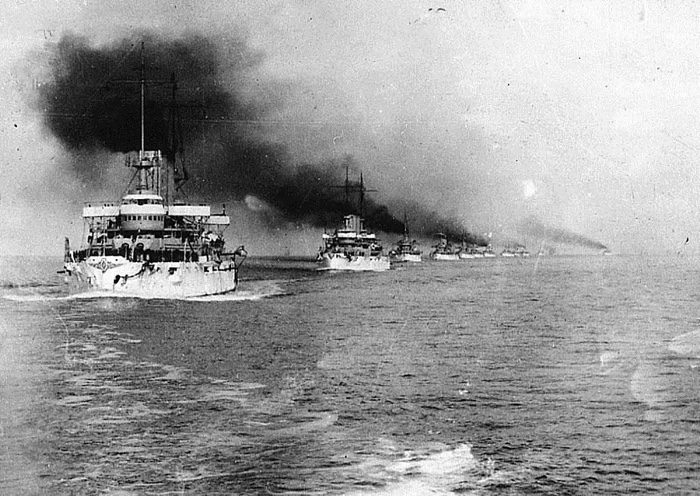

The Great Fleet Fleet departs Hampton Roads, December 1907. Photograph: US Naval History & Heritage Command. The most striking example of energy consumption from the pre-WW1 era was the Great White Fleet. Its circumnavigation consumed 430,000 short tons of coal

US Bradley fighting vehicles arrive in Lithuania following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014. Photograph: Mindaugas Kulbis/AP, via

The Pentagon, Climate Change and War is an illuminating and impeccably researched book. It is also reassuring to read that the road to climate safety doesn’t necessarily involve military conflicts. However, I wish the author had insisted more on the direct, toxic consequences of US military operations today. We are currently witnessing the disastrous impact that a military conflict has on the environment. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is not only a human tragedy, it is also the cause of growing environmental damage that include contaminated rivers and water tables, soils riddled with shrapnel and mines, air contaminated by toxic emissions from bombed industrial sites, risks of radioactive contamination, devastated natural reserves, etc. It might have been useful to read more about the U.S. own contribution to planetary destruction today.

Related stories: Ecologies of Power: Counter Mapping the Logistical Landscapes and Military Geographies of the U.S. Department of Defense and Blank Spots on the Map: The Dark Geography of the Pentagon’s Secret World.