Back in 1971, Nanni Balestrini wrote about the struggles of the Italian working class and the conflicts that took place in the FIAT car factory in Turin. The title of his book was Vogliamo tutto (We Want Everything). 50 years later, a group exhibition is taking its cue from the novel and invites the audience to reflect on the remains of our industrial past and on the metamorphosis of working conditions that emerged with the widespread adoption of digital technology.

LaToya Ruby Frazier, The Last Cruze, 2019. Installation view of the exhibition Vogliamo tutto. Installation view of the exhibition Vogliamo tutto. Photo: Hèctor Chico / Andrea Rossetti for OGR Torino

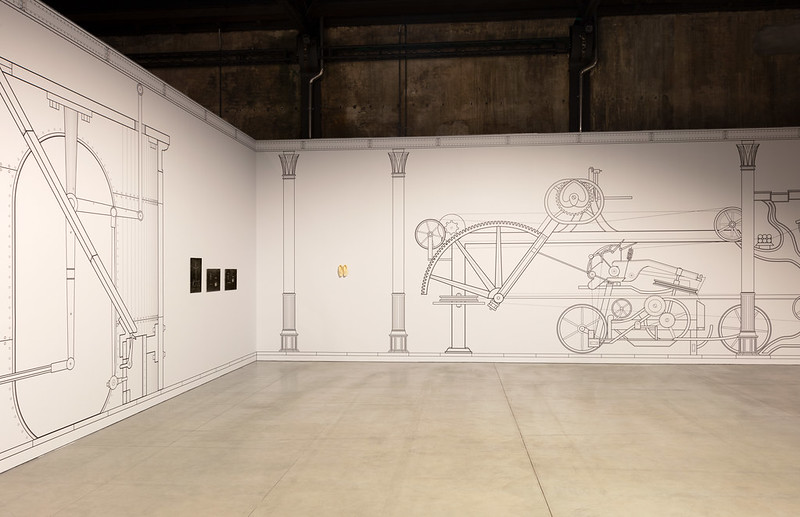

Installation view of the exhibition Vogliamo tutto. Photo: Hèctor Chico / Andrea Rossetti for OGR Torino

Over the past 2 decades, labour has gradually been reframed by digital economies and automation. A section of Vogliamo Tutto investigates whether or not yesterday’s frustrations, demands and victories are still relevant today. At the time of Balestrini’s novel, blue-collar workers were campaigning for more security in the workplace, fairer wages, fewer working hours, better conditions, etc. The workers of the digital economy still have similar aspirations. But the whole context has changed: the boundaries between the private and the professional spheres, between labour and leisure are increasingly blurred. In an era where neoliberalism has deregulated labour and dismantled production processes, no one dares to hope for “a job for life” anymore. Precarity is the new normal (and for some online marketplaces for freelancers, it is the new aspirational.) Long studies do not automatically grant you a prestigious career. In this new post-industrial context, how can workers fight for their rights? Can they learn from past struggles?

Vogliamo Tutto is a very interesting show. Over the past few years, there has been a fair number of exhibitions that attempted to dissect how digital labour has changed, radicalised or left untouched some of labour’s most pressing issues. As a result, I have blogged about most of the pieces exhibited in Turin already but here’s a run-through of some of the artworks I discovered at OGR and a couple of others you might have seen here in the past:

Elisa Giardina Papa, Technologies of Care (still from the video), 2016

Installation view of the exhibition Vogliamo tutto. Photo: Hèctor Chico / Andrea Rossetti for OGR Torino

Elisa Giardina Papa‘s video and installation are the results of interviews with precarious freelancers tasked with providing customised emotional and affective services through the internet.

One of these invisible, anonymous workers guides clients on how to set up a dating profile (I laughed out loud when one of the workers explained how one of her clients wanted to register on a Christian website with the alias “Cunnilingus King”.) Another is paid to pretend to be a fan of an influencer and interact with their social media accounts. Others are doing homework for students or playacting as a bot pretending to be a boyfriend or girlfriend.

The labour of empathy and emotional support is often outsourced to women from the Global South. With all the lack of recognition this means. It also often entails a covert, yet very drastic, discipline. Another element that emerged from the videos is that most of the care workers could probably do with some mental support themselves.

Giardina Papa found these freelancers on platforms like Fiverr and Upwork. The work is thus also the result of transactions where the artist is not just a researcher but also a client.

I don’t know how many hours of research, conversations and editing were required to produce this video but the result is gripping, moving and eye-opening.

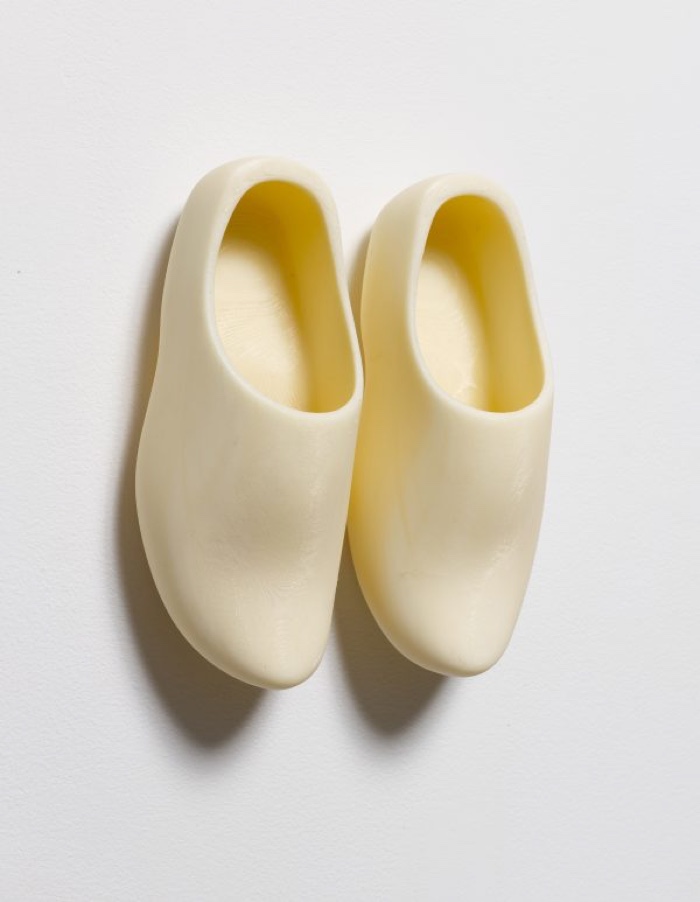

Tyler Coburn, Sabots, 2016

Sabots, means clogs in french. The word sabotage allegedly comes from it. The story says that when French farmers left the countryside to work in factories they kept on wearing peasant clogs. These shoes were not suited for factory works. As a consequence, the word ‘saboter’ came to mean ‘to work clumsily or incompetently’ or ‘to make a mess of things.’ Another apocryphal story says that disgruntled workers blamed the clogs when they damaged or tampered with machinery. A third version saw the workers throwing their clogs at the machine to destroy it.

In the early 20th century, labour unions such as the Industrial Workers of the World saw in the collective withdrawal of efficiency a legitimate means of self-defense against unfair working conditions. They called it sabotage.

Tyler Coburn’s 3D-printed clogs allude to the workers’ struggles during the Industrial Revolution. They were printed in a “lights out” factory, a production facility so automated that workers need rarely be present (hence, the lights can stay off). “Ostensibly products of the emerging automation economy, these plastic shoes also bear testament both to the history of industrial mechanization, and the forms of protest that emerged in response to it.”

Jeremy Deller, Hello, today you have day off, 2013. Installation view of the exhibition Vogliamo tutto. Photo: Hèctor Chico / Andrea Rossetti for OGR Torino

“Hello, today you have day off.” The banner, crafted by banner maker Ed Hall, is arresting: not because it is big but because the sentence itself doesn’t sound very correct to native English speakers. And because being told “today, you have a day off”, at the time of precarious employment and zero-hour contracts means that you will earn less money that month. In an exhibition where I saw the banner for the first time, Deller was drawing parallels between the Industrial Revolution and now. In the 18th and 19th centuries, only factory directors and managers owned clocks and watches. They were free to use them to their advantage and impose a strict time discipline that workers found hard to contest. Nowadays, zero hours contracts and their equivalents in the low wage sectors of the service and digital economy are reproducing similar imbalances of power and imposing another time discipline where the worker is informed often at short notice whether or not their labour will be required.

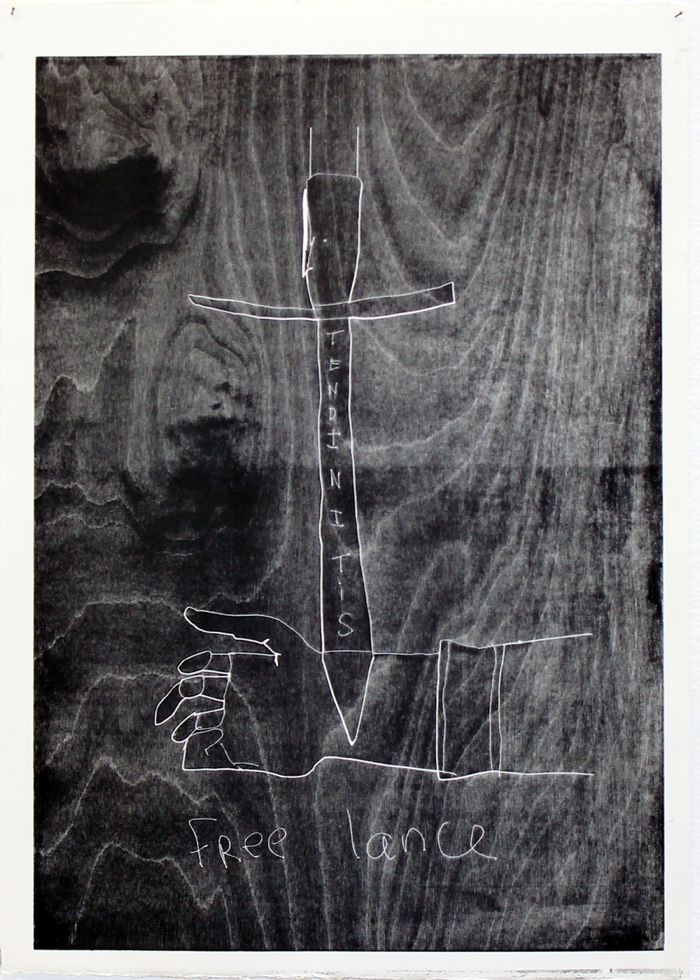

Sidsel Meineche Hansen, DONOR the manual labor series

Sidsel Meineche Hansen’s woodcut prints and laser-cut wooden plate comment on the myth of the disappearance of physical labour and the injuries they can engender. The series depicts the human autonomic nervous system (the control system that acts largely unconsciously and regulates functions such as the heart rate, digestion, pupillary response, urination, etc.) as well as hands injured by repetitive strain and affected by tendinitis.

Capitalism’s logic of profit strains the most intimate parts of our bodies, from our emotions down to the tendons of our fingers. The whole body is mobilised and absorbed by this logic and the invasive technologies that support it.

Claire Fontaine, Untitled (retour a la normale…), 2018

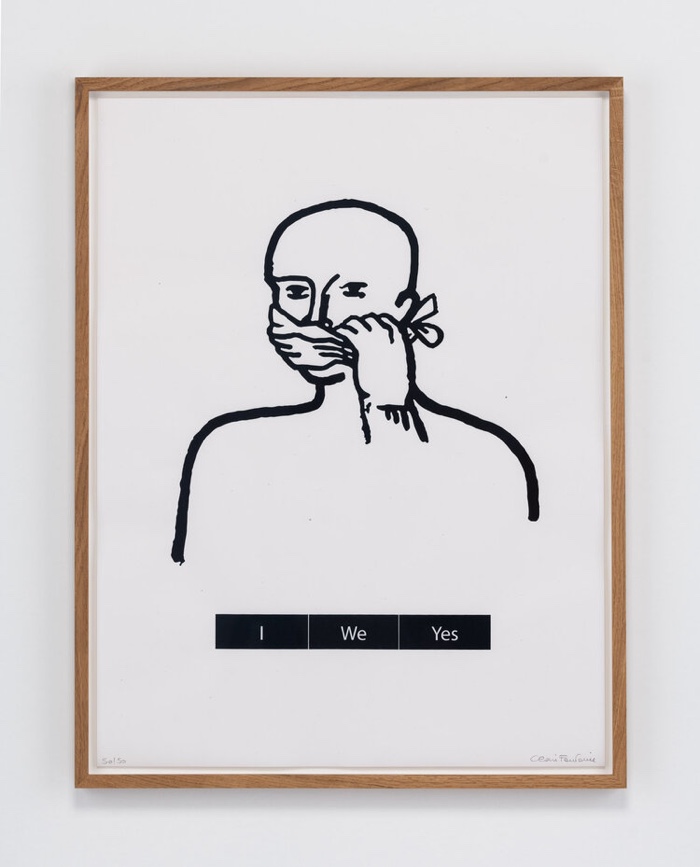

Claire Fontaine, Untitled (I We Yes), 2018

Claire Fontaine‘s silkscreens are inspired by the seminal protest posters printed by the Academy of Fine Arts in Paris during the civil unrests of 1968. The original posters were denouncing police violence, censorship, social inequalities, the marginalisation of young people but they also expressed a solidarity with the working class.

The collective altered some details in order to make them more relevant to today’s context. The sky over the sheep returning to the fold of everyday life is now studded, not with stars, but with social media symbols. With these small alterations, Claire Fontaine highlights how contemporary tools and languages of communication are similar to those used in the late 1960s, only more pervasive. The series also comments on the appropriation of past slogans by neoliberal interests that instrumentalise them in favour of their own interests.

Pablo Bronstein, We live in Mannerist times, 2015. Installation view of the exhibition Vogliamo tutto. Photo: Hèctor Chico / Andrea Rossetti for OGR Torino

Installation view of the exhibition Vogliamo tutto. Photo: Hèctor Chico / Andrea Rossetti for OGR Torino

The other part of the show considers the -architectural but also social and ecological- residues of a recent industrial past. The Officine Grandi Riparazioni (the venue hosting the exhibition) embodies the transition from industrial past to digital labour and culture. An icon of 19th-century industrial architecture in the city, the OGR used to ensure the maintenance of railway vehicles. Like many obsolete industrial infrastructures in Europe, the massive space has since been restored and revamped to host exhibitions, concerts, performances, workshops, start-ups and tech events.

Kevin Jerome Everson, Century, 2012. Installation view of the exhibition Vogliamo tutto. Photo: Hèctor Chico / Andrea Rossetti for OGR Torino

Century features the destruction of a Buick Century car. That particular model had parts manufactured in Kevin Jerome Everson’s hometown of Mansfield, Ohio, where Everson himself worked on a factory line. Watching a vehicle being crushed is always poignant, even if you are not a car fanatic. The demolition evokes the impact that deindustrialisation, delocalisation and automation have on the social fabric and the local economy. In the film, the mechanical arm crushing the car becomes a symbol of the industry crisis and the abandonment of working-class communities living in Rust Belt America.

Latoya Ruby Frazier, The Last Cruze, 2019

LaToya Ruby Frazier, United Auto Workers and their families holding up Drive It Home campaign signs outside UAW Local 1112 Reuther Scandy, Alli union hall, Lordstown, OH, 2019. From the series “The Last Cruze,” 2019

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Sherria Duncan, UAW Local 1112, at her kitchen table with her mother Waldine Arrington, her daughter Olivia, and her husband Jason, (23 years in at GM Lordstown Complex, trim and paint shop), Austintown, OH, 2019. From the series “The Last Cruze,” 2019.

All the tensions, despair and defeat felt by workers from the outmoded U.S. car industry awaken by Kevin Jerome Everson‘s Century film find an echo in the work of LaToya Ruby Frazier. The photographer spent a year with a community working at or/and living around a plant that manufactured the Chevrolet Cruze. Workers had just been told that the company was about to close the plant. Unionised employees received an offer to either keep their job and pension by resettling to another factory, perhaps thousands of miles away from their family and friends, or lose everything. She listened to their stories and documented their suffering.

Vogliamo tutto. An exhibition about labor: can we still want it all? was curated by Samuele Piazza with Nicola Ricciardi. The show remains open until 16 January at OGR in Turin.

Related exhibitions: The Promise of Total Automation, On the obsolescence of cognitive and creative labour, Post-Capital. Art and the Economics of the Digital Age, etc. And books: The Cost of Free Shipping. Amazon in the Global Economy, Augmented Exploitation. AI, Automation and workers who fight back, etc.