Last month, i had the chance to attend the Nonument Symposium dedicated to hidden, abandoned and forgotten monuments of the 20th century at CAMP, Prague’s Centre for Architecture and Metropolitan Planning.

Banner of Peace, Sofia, Bulgaria. Photo: HHS/MPAS

Destruction of the Mausoleum of Georgi Dimitrov in Sofia, Bulgaria

‘Nonuments’ are architectural structures that suffer from neglect, oversight and a lack of recognition. A nonument can be a hotel, a power plant, a high-rise building, a railway, a former anti-aircraft tower, a monumental sculpture in the middle of the city or in the middle of nowhere, etc.

Their status often raise heated debates. For historians and architects they constitute valuable parts of our built heritage. For tourists, they are often concrete clickbait, icons of ruin porn worth a selfie or two. For others, they need to disappear. Either for political reasons or for speculative ambitions. Or simply, as several participants have underlined during the symposium, because we already have so many monuments that require protection status,

Although nonuments can be found all over the world, the Symposium looked closely at several cases of nonuments from Eastern Europe where the structures often present an added layer of controversy. Many citizens and politicians from this area of the old continent see them as symbols of oppression. To them, they are outdated, inconvenient and “too Communists.”

Iriški Venac TV tower (detail), in Iriški Venac near Novi Sad, Serbia, 1975. Photo Fruskac

Iriški Venac TV tower (detail), in Iriški Venac near Novi Sad, Serbia, 1975. Photo Fruskac

The interdisciplinary symposium combined theory, documentation of artistic interventions, historical considerations and discussions with the public to reflect on how we should engage with structures that have intrinsic values but remain contentious.

One of the many issues that emerged during the event is that it is urgent to start a reflection around these structures before they fade into oblivion: their architects are dying and, all around us, public space is shrinking.

Nonument! Symposium at CAMP in Prague. Part 1

The videos of the symposium are online. I’ve embedded part 1 above. You can find part 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 on the fb page of CAMP. Below are some of the notes i wrote down while i was in Prague. This first chapter of my report is focusing on the historical and the architectural elements. The second chapter, which i’ll publish later this week, will look at the artistic interventions i discovered during the symposium.

Flak tower nicknamed “Peter” was part of Vienna air defence during WWII. Photo: Joshua Koeb

Flak tower in Arenbergpark, Vienna. Photo: Bwag

Let’s kick off with curator and art producer Jürgen Weishäupl’s investigation into the thorny legacy of Vienna’s six flack towers. Built between 1942 and 1945 by the Nazis to protect the historical centre of Vienna from Allied air strikes, the massive blockhouses are an embarrassing reminder of Austria’s darkest moments.

The Nazis had originally thought that after they’d had won the war, they would clad these concrete giants in white marble and convert them into victory monuments to fallen German soldiers. After WWII, the flak towers stood empty for many years. One is located within a military base of the Austrian Army, one has become an aquarium, one is used as a storage facility by MAK, one has been leased by a data company with a plan to turn it into data centres and several projects are considered for the others. To this day no official decision has been taken as to what the city should do with this difficult legacy.

Buzludzha monument. Photo

Inside the auditorium of the Buzludzha Monument, 2019. Image courtesy Nonument group

Inside the auditorium of the Buzludzha Monument while 3D scanning the whole structure, 2019. Image courtesy Nonument group

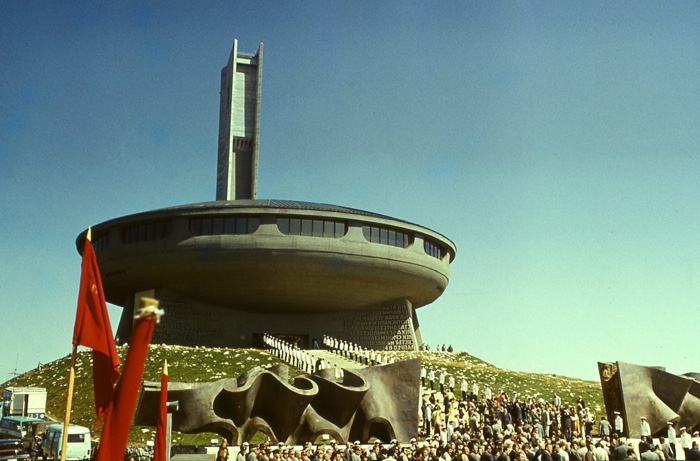

In her talk titled Buzludzha, aka “Bulgaria’s UFO”, – The Apotheosis of the Socialist Art in Bulgaria, art historian Aneliya Ivanova looked at the spectacular former headquarter of the Bulgarian Communist Party.

The Buzludzha Monument served the combined functions of a memorial, a museum and a ceremonial venue. It was built on the site where, 90 years earlier, Dimitar Blagoev and his followers had met to found the first social democratic party in the Balkans; where, in 1868, Bulgarian rebels fought against the forces of the Ottoman Empire. They lost the battle but it served as an inspiration for the Liberation of Bulgaria from the Ottomans ten years later.

Work on the monument began in 1974. 9 meters had to be shaved from the hilltop to give the structure its stable, prominent position. It was the biggest project in Bulgaria at the time. Extra taxes were collected and people had to donate and pay for special stamps in order to fund the construction. As a consequence, most people resented the project right from the start.

The Buzludzha Monument remained open for 8 years. After the government’s fall from power in 1989, the site was abandoned and left open to vandalism. Inside the monument, the mosaics have fallen to the ground and most of the artwork has been removed or destroyed.

Since January 2018, guards have been placed at the site to deter tourists from entering the building.

There’s been plans to turn the place into a hotel, a museum, a spa, etc. But that would of course require a lot of money and with each passing day, Buzludzha is becoming more of ruin. That’s why the The Nonument Group, an artist collective whose interventions attempt to bring more awareness to the issues caused by nonsustainable management of architectural heritage, have recently traveled to Bulgaria to do a 3D scan of both the inside and the outside of the monument.

Kiosk K67 as Tobacco and Newspaper Stand. Image Museum of Architecture & Design Ljubljana, via archdaily

Savin Sever, Mladinska Knjiga Printing House in Ljubljana. Photo via architectuul

Miloš Kosec, an architect and the author of Ruins as an Architectural Object, took examples from Slovenian modernist infrastructures to illustrate how and why some nonumental infrastructures have failed the test of time: an elegant printing house in Ljubljana that once closed never really found a way to be reused adequately; an entirely new city built on the Slovene-Italian border in 1948 along a 2 km long boulevard that started nowhere and ended nowhere; etc.

He did mention one structure that is still successful today: the wonderful k67 kiosk, a modular structure designed in 1966 by Saša J. Mächtig. It could be used as single units or combined to create large agglomerations. The kiosk has been used (and is still being used) as newspaper stand, parking-attendant booths, market stall, ticket booths, lottery stands, bee hive, etc. It has now been re-commodified as design icon and a mobile ruin offering endless reinventions, permutations and functions.

Kosec contrasted the kiosk with current forms of small urban infrastructure: CCTV, anti-terrorist bollards, anti-vandalism benches, anti-immigrant fences, etc. At first, it looked as if they would be ephemeral but they have become permanent. They might use the visual language of being flexible and transitory but they are here to stay. The other fairly recent architectural infrastructure he mentioned is the data center. Energy-hungry, often built in the middle of nowhere, with an extremely bland appearance to remain as anonymous as possible, data centres reflect the lack of transparency and accountability of today’s internet and remind us that infrastructure is not neutral.

Bolt958, Aktentát Transgas, 2017. An action to preserve the Transgas building in Prague. Photos

Ladislav Zikmund-Lender, a researcher in art history, gave a passionate speech in defence of the monuments and structures built over the past few decades. He also tried to examine the reasons why we are still unable to protect public and industrial buildings from the 1970s and 1980s Central East Europe.

Zikmund-Lender remarked that while most people lament the destruction or lack of renovation of buildings from the first half of the 20th Century, they tend to be indifferent when yet another building from the second half of the 20th century is dismantled and replaced by ugly shopping malls and other eyesores. For many people in Eastern Europe, these monuments are associated with communism, with an era they want to leave in the past. The demolition trend observed over the past 10 to 15 is not random he believes.

Hotel Praha in Prague

Hotel Praha’s grand staircase. Photo: Courtesy of Sigmar and OKOLO (via)

Hotel Praha’s bowling alley. Photo: Courtesy of Sigmar and OKOLO (via)

Hotel Praha in Prague is one of the examples the art historian gave of this trend. The Brutalist design dates from the early 1970s but the hotel was only finally completed in 1981. Its architecture closely followed the hill upon which it was erected. The spaces and furniture inside were the result of a collaboration between the best craftsmen, designers and decorators in Czechoslovakia. The hotel quickly became the location of choice for visiting communist dignitaries.

The hotel was privatized in the early 2000s. The new owner, perhaps not the most competent businessman in town, maintained that it was impossible to manage the hotel in a sustainable way. His claim was relayed in the press and so the hotel’s fate was settled. In 2014, in spite of the strong opposition from architects and historians, the hotel was demolished under the pretence that it was an unprofitable, unsustainable structure that couldn’t be fixed.

The building of Transgas, Prague. Photo: Ondrej Kohout

Zikmund-Lender also analysed the case of the Transgas building erected in Prague between 1972 and ’78 in the Brutalist style as a control center for the Transgas pipeline. Part of the complex served as the Federal Ministry of Fuel and Energy. At the time, people assumed that the state would take care of the building forever. But that didn’t happen. Politics changed and the public spaces were left to degrade. The Transgas building was being demolished while we were discussing its fate in the Nonument Symposium.

Zikmund-Lender ended his contribution to the symposium with 5 requests:

1. Stop pretending that this is not political! This architecture is socialist in many ways. It was paid by the state and it promotes the idea of modernity without capitalism.

2. Ask questions while you can. The career of the architects of these buildings plummeted after 1989. They were made to feel guilty, sometimes they were even fired from their positions. We have to talk with them, understand the circumstances and context of their work.

3. Forget Brutalism and Le Corbusier. In the East, architects of these decades knew about Le Corbusier and about Brutalism in France and the UK but they interpreted it in their own way.

4. Your building is our city: public interest and not just private interest has to be taken into consideration. We don’t need new buildings, we need to think about the carbon footprint of new constructions.

5. Stop lying about the real reason to take down these buildings. Instead, research, understand and don’t judge. Fight and resist their demolition.

Bratislava Castle, Baroque garden. Photo

Architecture historian Peter Szalay recounted the absurd history of the renovations of the Bratislava Castle. Burnt in the 19th century, the castel was left as a slowly deteriorating ruin until the middle of the 20th century. It was then remodelled in a Neo-Romantic style with a decidedly modern interior. The castle has recently been revamped again. This time in Neo-Baroque style with white stucco and gold that are supposed to bring back a certain idea of the glorious past of the city.

Things got even stranger when it was decided to build a garage under the castle. Remains of Celtic cities were found underground but, instead of renouncing the parking lot, the city decided to quietly push aside some of the Celtic remains into a small space. Then they built the garage and put a Baroque garden on top. The decision demonstrates the irrationality of this type of nationalism, the self-narcissism of a choice one would expect from an absolute monarch.

Similar manipulative rhetoric is sometimes used to justify the destruction of modernist buildings, Szalay concluded. Sometimes the destruction is presented as being part of a “healing process”, sometimes it’s the “un-ecological state” of the building that is used as an excuse.

Mihajlo Mitrović, Western City Gate, 1977. Photo by jaime.silva

Mihajlo Mitrović, Western City Gate, 1977. Photo by Błażej Pindor 2003 (via)

Historian Vladimir Dulović brought our attention to the fate of the Genex Tower, aka Western City Gate, one of the icons of New Belgrade and its brutalist architecture. A symbol still visible, but now almost abandoned.

Western city gate was built in 1980 in the brutalist style by architect Mihajlo Mitrović. It is formed by two towers connected with a two-storey bridge and a revolving restaurant at the top. The taller tower is residential, while the other one was owned by the Genex company.

After the war, socialist Yugoslavia was perceived as negative and embarrassing. The Genex tower was left empty and is now covered by a huge billboard, the concrete shows signs of damage and the communal areas are left in very bad conditions. The owners have tried several times to sell the building but no one was wants to bid. On the other hand, Brutalism is very fashionable again, tourists in Belgrade are eager to see “something very communist” and residents of the tower understand that the place still has a lot of potential. However, the government is not intervening and most people within Serbia don’t appreciate what they see as “Socialist architecture”. What protects the building now are the residents who live there and its huge size (it enjoys the aura of being the tallest building in Belgrade but not for long.)

Western City Gate is a monument to its own era and also to the way we’ve been treating the monuments of these past few decades.

Hybrid Space Lab, Virtual recreation of the Valley of the Fallen

Elizabeth Sikiaridi and Frans Vogelaar from Hybrid Space Lab, a interdisciplinary platform for architects, urbanists, designers, media artists and engineers, introduced us to Deep Space, a long-term investigative program that explores politics of memory, controversial space and monuments, digitalization and heritage.

One of the cases they are working on at the moment is not located in Eastern Europe but in Spain. Valle de los Caídos (The Valley of the Fallen) is a vast complex hosting a Francoist regime monument, a basilica and a monumental memorial in San Lorenzo de El Escorial, near Madrid. Franco claimed that the structure symbolized reconciliation after the civil war. Which is a bit cynical when you know that the structure was built partly by the forced labor of Spanish republican political prisoners and that after his rise to power, the Caudillo continued to persecute and kill political opponents.

Valle de los Caídos hosts a mass grave containing the bones of 33,000 combatants of a conflict that Franco contributed to by helping to lead a military coup against democracy. Only two graves are marked: the one of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, the founder of the Falangist party, and Franco’s, the only person interred in the Valley who did not die in the Civil War.

Hybrid Space Lab is exploring ways to re-signify, to bring new meaning to the controversial place by adding an Augmented Reality layer that would allow “the other side”, the one of the victims of the regime, to finally contribute to a narrative that has so far glorified a painful moment of the history of Spain. Deep Space also suggests creating a Center for Civil War Research and a Global Center for Peace and Interpretation inside the site’s buildings.

Jan Kempenaers, Spomenik #1 (Podgaric, Croatia), 2006

Jan Kempenaers, Spomenik #9 (Jasenovac), 2007

Art historian Branislav Dimitrijevič closed the symposium with a brilliant keynote titled “Egypt” rather than “October”: Incongruences in Interpreting Yugoslav National-liberation Monuments, Then and Now.

He looked at the debate around Spomenik, the Yugoslav memorials that went viral online after Jan Kempenaers photographed them in 2010. The photos glamourized the monuments and introduced them into the canon of modern sculpture. However, warned Dimitrijevič, the photos show structures isolated from their surrounding which gives them a fascinating aura of mystery, exoticism and otherness. Both the historical and the geographical contexts are excluded from the canonisation of these sculptures. In this type of vision, they are commodified and exposed to commercial exploitation. Countries from ex-Yugoslavia need to reclaim this part of their history and bring it into a more thoughtful, more nuanced light.

Nonument is an ongoing research and artistic project initiated by MoTA – Museum of Transitory Art in Ljubljana. The two-day art and theory symposium was organised by Yvette Vašourková, an architect and founding member of CCEA MOBA, the Centre for Central European Architecture in Prague in collaboration with Neja Tomšič and Martin Bricelj Baraga from MOTA.

If you want to know more about the project, check the growing database on Nonument website which is part of MAPS, Mapping and Archiving Public Space co-operation project. Six organisations have contributed to this database: the Centre for Central European Architecture: CCEA (Prague), WH Media / Beamy Space (Vienna), Tačka Komunikacije (Belgrade), House of Humor and Satire (it’s in Gabrovo and i want to go now), ARTos Foundation (Nicosia) and MoTA – Museum of Transitory Art (Ljubljana). The project is co-financed by Creative Europe.