Extremophiles are organisms that can withstand such unforgiving conditions that they’ve survived every mass extinction on earth and are expected to be the first sort of extraterrestrial life space explorers might discover one day.

Xandra van der Eijk, Genesis. Image: Xandra van der Eijk

Geothermal hotspring, Iceland 2016. Image: Xandra van der Eijk

What designer and artist Xandra van der Eijk found fascinating about these tiny and simple organisms is not just their remarkable sturdiness but the fact that they modify their colour when their environment change.

In her research project Genesis, the designer studied their color properties. First she traveled to Iceland and France where she sampled fluids from volcanic hot springs and high saline ponds and isolated strains that produce pigments. She then collaborated with Arnold Driessen, a professor in Molecular Microbiology at the University of Groningen, to understand and eventually influence the pigment production of the microbes, inducing color change over time. “With Genesis, Xandra is hacking the origin of life, ultimately questioning who is in control.”

I discovered the work of van der Eijk a few months ago when she exhibited As Above, So Below at the Artefact festival in Leuven, Belgium. The research project explored the possibility to “crowdmine” stardust fallen onto the surface of the earth as a new source for rare earth metals.

I caught up with the designer and artist to talk about space mining without going to space and about controlling or being controlled by microorganisms. If you’re curious about her experiments with colour-changing extremophiles, check out her installation at the Science Gallery in Dublin where it is part of Life at the Edges, a show that explores survival in extreme environment, helping us contemplate our future on a planet exposed to increasingly unstable environmental conditions. In the meantime, here’s what our little Q&A looked like:

Xandra van der Eijk, Genesis. Image: Xandra van der Eijk

Science Gallery Dublin where the work is exhibited as part of Life at the Edges, a show that explores survival in extreme environment, helping us contemplate what our own future on a planet Earth battling with increasingly unstable environmental conditions.

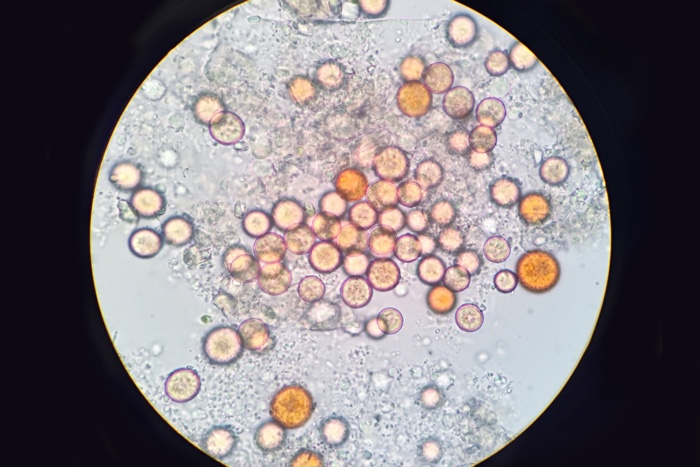

Hi Xandra! For Genesis, you took samples from volcanic hot springs. They contained extremophiles, ancient micro-organisms that can survive in extreme conditions and also produce pigments. I found it fascinating that these tiny creatures produce pigments. Could you tell us about the kind of pigment they produce and how they make it?

I think ‘how’ they make it is a big mystery still, but these specific organisms have developed the production of pigments as a sort of defense mechanism to sunlight. The UV can get really intense, and the pigments are like sunscreen to them!

Why did you want to manipulate the color of these microbes?

First I wanted to show their mere existence and tell their story to the public. The organisms are so small, they can only be seen under the microscope. The fact that they produce color brought me to the idea that their existence would become visible through cultivating large numbers. In my projects I research the interrelation between the subject and myself, myself being a standing for human kind. I found an organism that would change color depending on specific circumstances, and I was curious if I could manipulate this metamorphosis.

Xandra van der Eijk, Genesis. Image: Xandra van der Eijk

Xandra van der Eijk, Genesis. Image: Xandra van der Eijk

And how did you change their colour? Could you describe the work process and explain the kind of techniques and technology you used to do so?

I have no biology background, so I sought help to understand the ways of the extremophiles and well, microbiology in general. I found it at WAAG Society, where a bunch of great people were willing to show me the ropes. Together with Federico Muffatto I set up a series of experiments trying to isolate and cultivate certain species. And later on with Arnold Driessen of Groningen University I set out another series of experiments figuring out the exact parameters needed for color change. Different organisms produce pigments reacting to different parameters, so it’s hard to give one conclusive answer. But in general, the extremophiles have an ideal environment for growth, and when something in this environment changes, they may react in color change. Think about changes in water temperature, UV intensity or salinity.

Do you think that since they are able to survive or even thrive under extreme conditions, extremophiles could teach humans a thing or two about surviving in increasingly unfavourable environments?

Maybe! For now I am mostly admiring these tiny organisms that can do something we can’t. But who knows what we can learn and adapt from them by studying their behavior. I think it is a very interesting and promising field of research.

For this work, you collaborated with Arnold Driessen, a professor in Molecular Microbiology at the University of Groningen. Could you tell us about this collaboration and in particular how his feedback guided your own work?

And conversely, what you think he might have maybe gained from your artistic perspective on molecular biology? (i can rephrase that one if you think it’s a bit clumsy or too narrow a question)

My experience with Arnold so far has been very positive. There is a very open attitude in the overall collaboration from both sides. The reason why we collaborate is because he leads a research group focused on extremophiles, so we have a strong mutual interest. It has been truly great to find someone so knowledgeable about the subject, it gives my research a clear outline of what is possible and what isn’t, and what makes sense and what doesn’t. It’s too early to say anything about what the project might mean for his own research, but I am lucky that Arnold sees the added value of art in general. He is even somewhat of an artist himself, he takes amazing wildlife photographs!

Why did you call the work “Genesis”? How does the work relate to the Biblical description of the origin of the earth?

It is called that way because we believe extremophiles to be one of the earliest lifeforms on earth, perhaps even the very first — maybe they even traveled here as aliens from outer space. The piece is about who is in control: human or microbe. In that sense I like the biblical reference. In many ways these extremophiles are superior to us. And it’s no secret that microbes control our decision making process…

Genesis at Science Gallery Dublin. Installation view

I’m still hoping i can catch the exhibition Life at the Edges at the Science Gallery in Dublin but so far i haven’t found the time to travel and visit it. How do you exhibit the work there? What does the installation look like and how does it communicate its meaning?

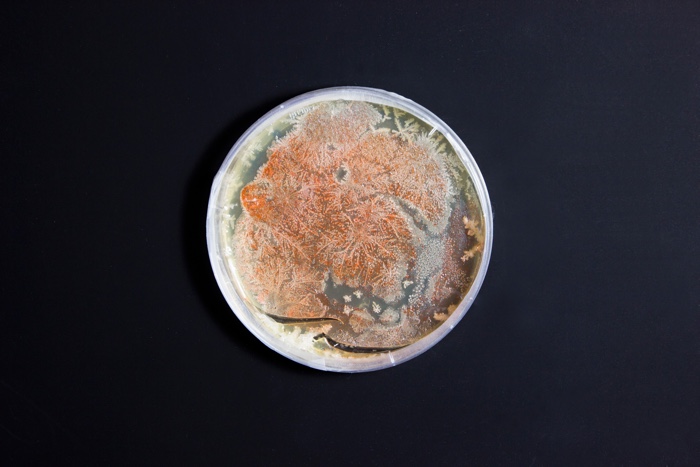

The exhibition shows the very first step towards a more developed artwork. Working with living material in an exhibition environment is really hard, especially if you are not looking for a lab-setup. I wanted to recreate the manmade landscape of the salt harvesting area’s where I took samples from, as it is a beautiful and rare example of how man and nature can work together and both profit from it. It is one of the eldest manmade landscapes in history, and the process hasn’t changed much over time. Basically we still harvest salt like the Romans did — creating a large biodiversity in the pools. At the Science Gallery I show a grid of nine square glass containers, all with partly filled with the same extremophiles, but in different circumstances. After setting the parameters, the containers are left alone and the organisms show their response towards the parameters in colors and patterns.

Kirstie van Noort & Xandra van der Eijk, As Above, So Below. Photo by Ronald Smits Photography

Kirstie van Noort & Xandra van der Eijk, As Above, So Below. Photo by Ronald Smits Photography

I’d like also to ask you something about another of your work As Above, So Below. I love that one. It’s both charming and very smart. The work is a research into crowdmining stardust fallen onto the surface of the earth as a new source for rare earth metals. For the work, you collaborated with Kirstie van Noort to harvest stardust from the urban environment. How did you identify and collect stardust? How difficult is it to then extract the micrometeorite particles?

It is actually an urban myth, collecting stardust on the streets and from the roofs. The first amateur scientist who really proved their existence was Jon Larsen, and he has fought hard and long for the recognition of their existence. We were inspired by his work and took the idea one step further: what if we would collectively take the effort to collect stardust — what kind of materials would we find and could they form a new resource of precious metals? We took to the roof and the streets, collected a lot of dirt basically, and dried it out. From the dust we sorted small spherical particles and examined them under the microscope. We do not claim we found any, although the project shows a selection of specimens that might be, and one we are quite sure of. But we still need to find a university who would be willing to collaborate with us and find out about what we found. In the end, I guess we were most surprised by how much you can find in your own backyard, whether it’s from outer space or not.

Kirstie van Noort & Xandra van der Eijk, As Above, So Below. Photo by Ronald Smits Photography

Could this practice become, over time, a viable alternative to traditional raw materials dug up from the earth at great ecological costs or mined in space?

I don’t see it as a replacement for large deposits of earths metals and minerals, rather as a possible resource for small quantities of precious metals, and perhaps even of materials that we don’t know yet. Who knows what role they could play in our technology, where sometimes only very small quantities are needed due to very specific characteristics of a metal or mineral.

What is next for you? Any upcoming event, fields of research or project you would like to share with us?

I presented a whole new research into chemical dumping called Future Remnants in April, which I am still working on and presenting a lot. It’s been nominated for the New Material Award. I am already working on something new that will be presented at Dutch Invertuals in October and of course I will continue my research with Groningen University. Many other nice things ahead, it’s a crazy rollercoaster of a life that I am enjoying a lot!

Thanks Xandra!

Genesis is part of Life at the Edges. You have until until 30 September to visit the exhibition at Science Gallery Dublin.

Also part of the show: Drosophila Titanus by Andy Gracie.