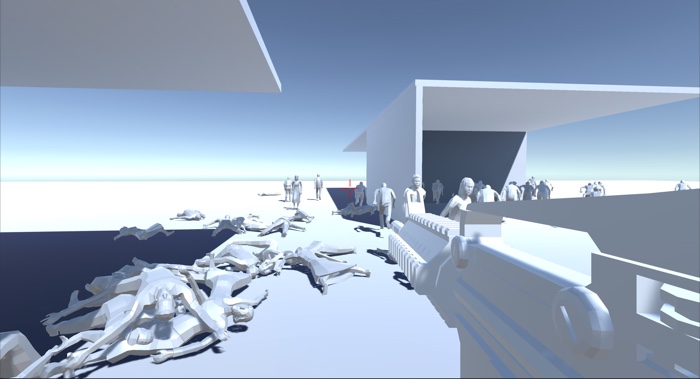

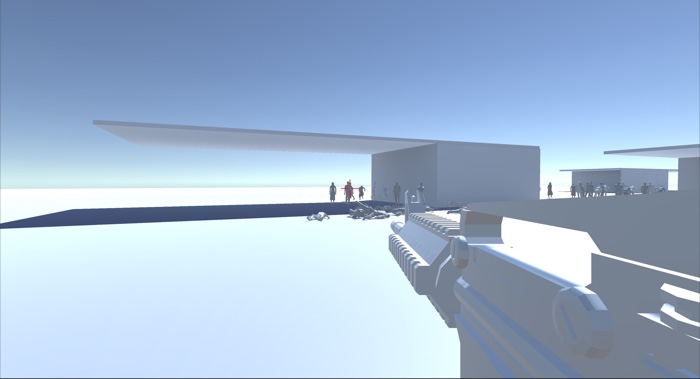

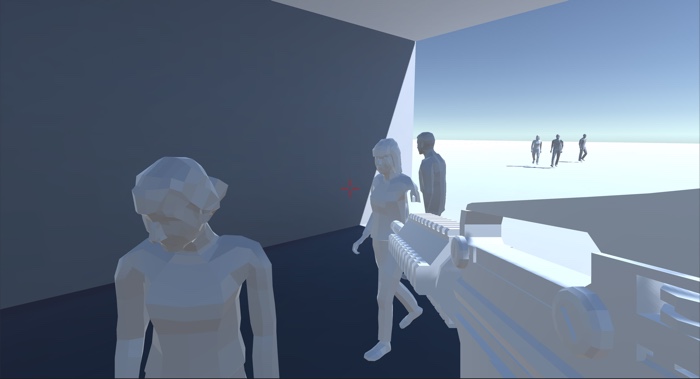

Karolina Sobecka, Medusa FPS (caption from the video game)

The military is increasingly using smart robotic weapon systems that distribute agency between a team of men, an algorithm and a machine. This type of weapon means that any sense of responsibility and accountability is shared and thus diluted. If that were not disturbing enough, personal weapons used by civilians are now being fitted with similar ‘smart’ technology. The Tracking Point Rifle, for example, won’t allow you to pull the trigger until it has been pointed in exactly the right place. It is an extremely precise and sophisticated piece of machinery that takes into account dozens of variables, including wind, shake and distance to the target. The weapon also comes with a wifi transmitter to stream live video and audio to a nearby iPad. Every shot is recorded so it can be posted to YouTube or Facebook should you wish to.

Karolina Sobecka‘s Medusa FPS is directly inspired by these semi-autonomous and autonomous weapons. In her First Person Shooter game, the player uses an AI-assisted gun that guides his or her hand to aim more effectively and fires when a ‘target’ enters its field of view. Which of course seems to wipe out much of the thrill of playing an FPS game. Medusa FPS, however, reverses the usual logic and goals of FPS games. The challenge for the player here is to fight against his or her own in-game character and prevent it from shooting anyone. They cannot drop the weapon nor stop it from firing, but they can obstruct it (and the gun’s) vision.

Medusa FPS hinges on the conflict created between the player and her in-game character. Virtual environments have allowed us to create and play out multiple personas, and thus allow for potentially creating an internal dialog between those. The POV perspective used by the game convention helps to set up such a confrontation here. The vision is shared between the player and the character, and is a place of contention of either’s agency.

Medusa FPS is part of Monsters of the Machine, a show that explores the ‘unintended and dramatic consequences’ that technology can have for the world. The exhibition was curated by Furtherfield.org co-director Marc Garrett and it features a few of my favourite artists. One of them is Karolina Sobecka and i thought i’d take the excuse of the Laboral show to get in touch with her and have her talk about the game:

Exhibition view at Laboral. Photo by Marcos Morilla

Hi Karolina! i must admit that i was totally shocked and horrified when i read the full description of the conceptual and technological background of the game. I had no idea that personal weapons could become so dangerously sophisticated. The possibility of sharing the shootings on social platforms is particularly chilling. How do you ensure that people who come in the gallery and play the game actually engage with the issues rather than just enjoy it as a new gaming challenge?

I was pretty surprised when I learned about the ‘precision-guided’ personal weapons too. The TrackingPoint rifle really just sounds like a grotesque exaggeration of the trends in ‘smart’ things and in the need for experience to be dramatized by social media. And yes, the live streaming of the ‘shot view’ is probably its most disturbing feature, partly because you can see the profit logic in this design. This really quickly becomes also a question of the responsibility of online media that benefits from this kind of material. Incidentally, we now already have a discussion of how the presence of social media might be encouraging people to create a certain reality on the ground thanks to the recent murders that were being streamed or posted on Facebook.

Fortunately, it looks like the TrackingPoint startup is not doing great. Apparently the guns, besides being very expensive, ‘take the fun out of hunting.’ And also, the rifle has already been hacked (to remotely change the target), so at least it serves to illuminate some of the vulnerabilities of privately owned networked weapons.

A view through the scope of the Tracking Point TP750. Photo: Greg Kahn for WIRED

My project was actually inspired not by TrackingPoint but by reading Mark Dorrian’s essay ‘Drone Semiosis’ about the autonomous weapons systems (such as Gorgon Stare), which, as he writes ‘conflate the act of seeing and killing.’ I think it demonstrates the violence of surveillance in general, that violence is implicit in the act of targeting. The other really complicated issue Dorrian writes about is the distribution of the responsibility for killing between several human and non-human actors. That’s really interesting and ideally, my project can compel people to think about it.

The game is only presented in art galleries, so I think the context encourages the viewer to reflect on it as a critical material. The game itself is quite simple, and the metaphor – which is the formal device – is encountered right away. The design is centered around this dissonance between what you expect and what you experience when you first start playing. I hope that just the initial moment of having to re-calibrate – to stop and think about one’s action, is enough of an interruption of the habit to cause some reflection.

Karolina Sobecka, Medusa FPS (caption from the video game)

And where do you think that these ‘monsters in the machine’ are going to lead society? How far can we push the limits of what is ethically and socially acceptable?

On one hand, this monster could be the traces of the humans that made it, their biases and agendas buried in the design of the system, while the actual human with his critical reflection, re-negotiation and re-evaluation has been de-coupled from it. This might be the hidden monstrosity, but what I think actually produces a sense of threat is the uncertainty, apprehension towards the unknown. The gamble is bigger in the context of a global networked society, which means that risks associated with technologies can have a more far-reaching impact.

AI making decisions that are moral in nature, and act on them is a complicated question. I think this is something we will have to grapple with for some time – it takes time for people to be exposed to this reality to think about what consequences it might have, see examples of how it unfolds, and develop narratives of what’s acceptable and what isn’t. I think the drones are a good example to think through the ethics of integrating decision-making software into social systems, because when harm is done the stakes are so high – someone is killed. It might be even more difficult to analyze systems when the effects, and who benefits or is harmed, might be more subtle or just invisible. Weapons are ostensibly violent but perhaps a more insidious kind of violence can be done as a result of entrenching a technology that exploits people under a banner of freedom or economic independence.

But I tend to agree with the standard answer to this question – that the technology develops first and then our ethics have to try to keep up, so it is important that we analyze, reframe and hack technology from the very beginning of its development, to constantly apply the critical lens to it, and to keep in check the potential of the harmful consequences.

And have you noticed that people engage and react differently to Medusa FPS depending on whether they are avid players of FPS games or gallery visitors who are interested in the concept but less used to the mechanic and logic of FPS games?

I don’t really have an answer to this. I haven’t gotten a chance to see how people interact with this in a gallery. And honestly (and this might sound antithetical to game designers) I am more interested in the concept than the game playing myself – I love designing interactive systems, but I’m a really bad player.

Karolina Sobecka, Medusa FPS (caption from the video game)

I don’t know if this is relevant but looking at screenshots from the game and reading your text, there seem to be a strong feminine presence in the game. In the role of the potential victim of a bullet but also in the way you describe the work, using ‘she’ where one might have expected a ‘they’ or even a ‘he’. for example: “The player cannot drop the weapon or stop it from firing, but she can obstruct her (and the gun’s) vision.” Is this something you’d like to comment on? Is this a feminist statement?

I used an equal number of male and female characters but all of them are just plain people models rather than soldiers or fighters, which might contribute to this impression of ‘feminine’ presence. The masculinity of the men is not exaggerated as it would be in standard FPS characters. It wasn’t meant as an overt feminist statement. It’s just shifting what the standard of FPS is in terms of genre: where the enemies are predefined and unambiguous, including how they look and act.

Could you describe how the interaction unfolds? What the player has to do that will enable him/her to obstruct the gun vision and shoot as few people as possible?

The player has to hide within the building structures or stay away from anybody else. The people in the scene simply walk around the world. When they are shot at, they start running away or trying to attend to the ones who were shot. They actually are controlled by a modified ‘AI’ script, so their behavior is the result of several simple rules. They run away to a safe distance and then resume their wandering behavior. They are curious (so if the player is in their field of vision they’ll walk to approach him), and sometimes attracted to being in a group. The term AI in games that connotes autonomous behavior of an agent (usually enemy) has been around for a long time, but it usually is just a very simple behavior based on a few rules. Now that Artificial Intelligence is starting to control devices and agents in our daily lives it might be interesting to look at those really simple standard behaviors.

The player doesn’t get much chance to watch the pattern of their behavior. There’s an AI script on the weapon as well – which exaggerates ‘guided aiming.’ I have heard that in some games weapons can be in fact scripted in a similar but more subtle way, making the player a more effective shooter. In my game, if there’s a person within the field of view, the weapon will rotate to get them in the crosshairs – and when they are in the crosshairs, it will fire. Player’s control will override any movement by the weapon but the moment he or she stops exerting active control, the weapon will take over do its automatic guiding. In practice, this looks like jerking the gun back and forth. It’s a strange interaction because it doesn’t correspond do anything in physical reality. The immersive illusion of the game rests mostly in the POW camera. But this wrestling of control happens with the keyboard.

Could you also explain the choices you made while designing the visual universe of the game? Why is it so cold and clean?

I’ve been using this palette and character design for some time, it’s in a way just a pragmatic choice – since I’m interested in the rules of the game, rather than building an immersive world, the visual quality should support that. It’s a model rather than an illustration or a narrative, and this design is a bare-bones model, where everything that I’m not trying to point to is at a default value.

Thanks Karolina!

Medusa FPS is part of the exhibition Monsters of the Machine, curated by Marc Garrett, co-director of Furtherfield.org. The show remains open until 31st August 2017 at Laboral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial in Gijón.