Previously: Bodily Matters: Human Biomatter in Art (part 1. The blood session).

Bodily Matters: Human Biomatter in Art (part 2. At the morgue).

Part three of the notes i took during Bodily Matters: Human Biomatter in Art. Materials / Aesthetics / Ethics, a symposium that took place a couple of weeks ago at University College London. The impeccably curated event explored how artists use the human body not merely as the subject of their works, but also as their substance.

Dr. Laini Burton speaking at Bodily Matters

Bioengineering, 3D cell printing. Photo: Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, via Gizmodo

The third and last session of the day was titled ‘Second Skins.’ I’ve searched everywhere, even inside the laundry bag, but it seems that i’ve lost the notes i was taking during the second part of that session. So all i’m left with is what i scribbled while listening to Dr. Laini Burton (Griffith University, Queensland College of Art.)

Her talk Printed flesh, fashioned bodies investigated how we fashion our bodies and speculated on the many shapes that the human form might adopt in the future with the help of science, technology and engineering. By doing so, Burton is hoping to prompt a conversation about how we value body. She wrote in her abstract of the talk:

Contextualized through a discursive range of examples spanning across art, design and popular culture, this paper will reflect on some of the ethical implications that arise when considering biofabricated flesh as a medium. In particular, it will consider whether the examples enacted in cultural production will transcend the imagination to become adopted within mainstream culture in the future. In doing so, it will ask the question: Will such a development embolden us to redesign our bodies, where we no longer need to commit to one ‘look’ or ‘style’ but can embody a range of features in a fashioning of the flesh?

3D printing technology is particularly promising in the medical field. It can be used to create noses, ears, lips and other facial parts that trauma patients have lost or that have been damaged. It is particularly useful in Australia where skin cancer is rife.

The 3-D printed parts feature realistic skin color. Photo: Fripp Design via Wired

Because they are made of bio-compatible materials, the 3D printed parts have to be replaced regularly, every 6 to 12 months approx. But the original file can be saved and easily reprinted on demand. Burton sees this as data and flesh grafted together.

The leap in 3D printing capabilities means that one day we might see the technology as a panacea for all physiological problems but we might also start considering living matters as being expendable, as being something that we can swap, recompose and replace easily. Applied outside of the medical field, 3d printing could become an important asset in cosmetic surgeries. Cosmetic fanatics wouldn’t have to commit to one look, to one style.

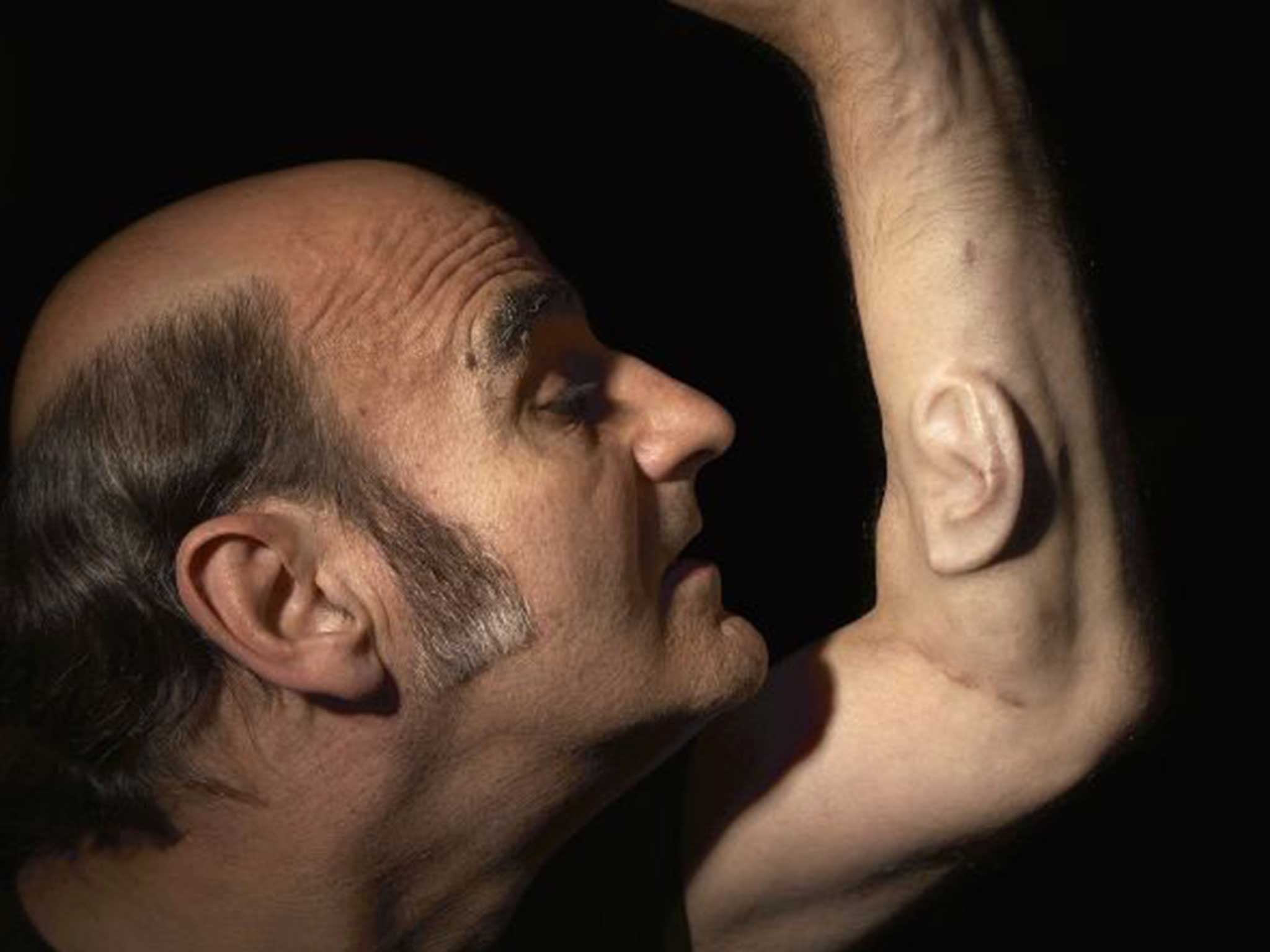

Artist Stelarc and his third ear. Photo AFP via The Independent

Burton suggests looking into art and designs as disciplines that stir technological processes into the broader cultural debate.

Early proponents of the recomposed, unstable and reproducible flesh are obviously Stelarc and Orlan. Both are pioneers in the way they invite us to reconsider the relationship between the body and the technologies we use to transform it. Stelarc believes that the way we consider the body is obsolete:

“It is no longer meaningful to see the body as a site for the psyche or the social, but rather as a structure to be monitored and modified,” he wrote. “The body not as a subject but as an object – not as an object of desire but as an object for designing.”

Henry Damon, left, has altered his face to look like Red Skull. Photograph: Getty

In certain subcultures, transforming the body is a form of self-expression. An extreme case of this is Henry Damon who cut off his nose, had subdermal implants in his forehead and tattooed his face red to look like Marvel villain Red Skull.

We could also add the examples of the Human Barbie and the Human Ken Doll.

With the arrival of 3D printing prosthesis using bio-compatible material, we might see more and more of these extreme body modifications reaching the mainstream. What could once only be imagined is now only a matter of time. In the future, designer flesh could be a fixture of beauty and fashion.

Burton also noted that when she is talking about modification, she’s not considering elective amputation which is often the result of Body Integrity Identity Disorder called apotemnophilia.

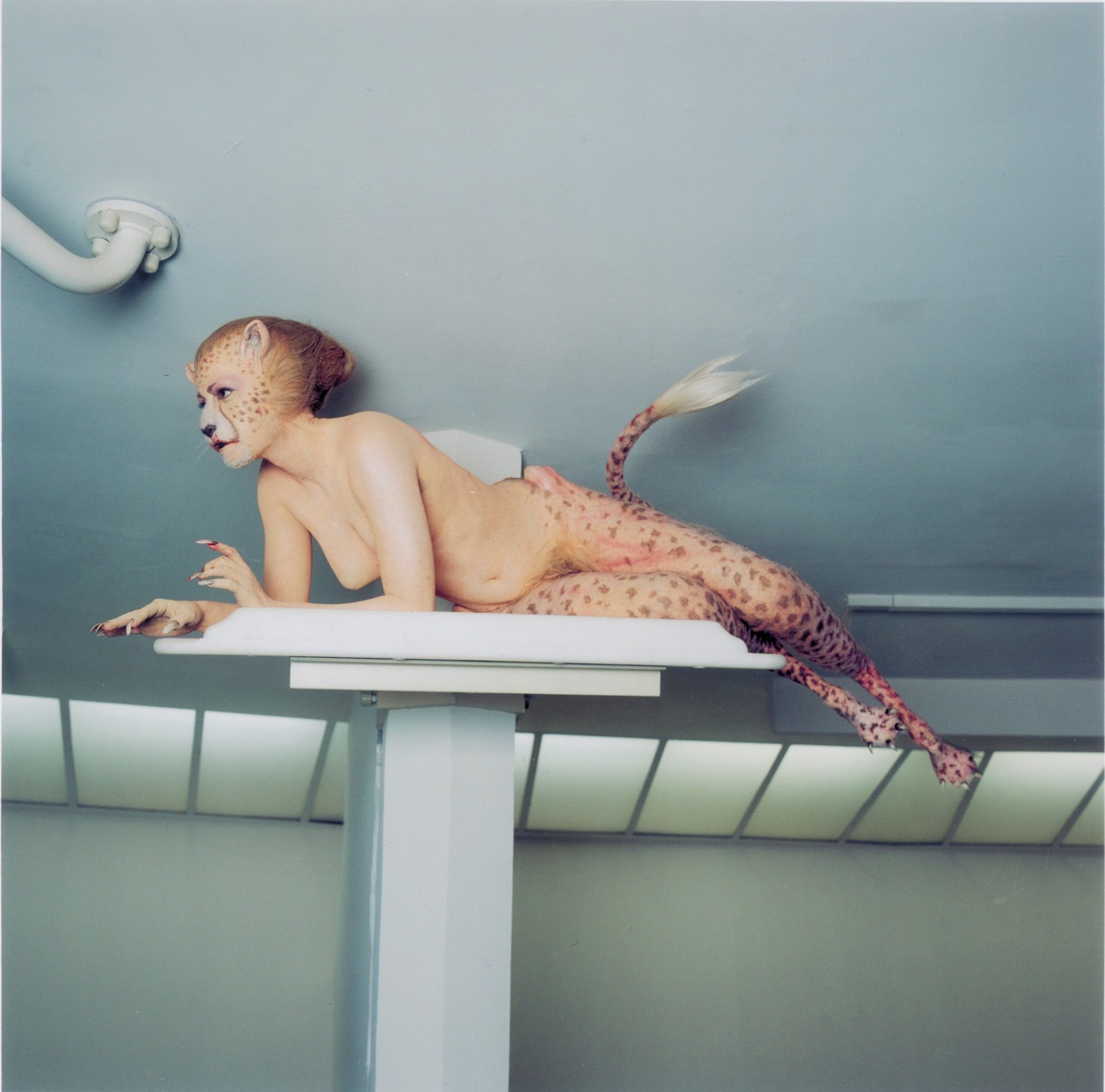

Aimee Mullins in Matthew Barney’s Cremaster Cycle

Hyper sophisticated and customizable prosthetic body parts could give rise to prosthetic envy. Athlete and model Aimée Mullins has inspired many artists and designers. She appeared in Matthew Barney’s Cremaster 3 as six different characters. She owns a wardrobe of different sets of lower legs (including the wooden ones made for her by Alexander McQueen) that she picks up according to her mood. The famous “Cheetah” carbon-fibre sprinting legs (still worn by athletes nowadays) were designed for her in 1995.

Viktoria Modesta, Prototype

Viktoria Modesta, “the world’s first amputee pop artist”, also chose to embrace alterity. An article about the artist in The Guardian explains that her prosthetics are made by the Alternative Limb Project. Company founder Sophie de Oliveira Barata says about her clients: “They appear to hold themselves more proudly. I think this is a combination of how it feels to wear the piece itself and the fact that they have been so involved in the process. Generally, when [my] clients wear their prosthetic limbs, they receive positive attention, as it breaks down barriers. Rather than pity, people view them with curiosity, and in many cases have even shown signs of genuine envy, all of which is empowering for the wearer. Some clients reserve their alternative limbs for special occasions, and in those moments they can explore an alter ego. Others see it as part of their day-to-day identity.”

These two cases, as well as the high performances achieved by athletes wearing prosthetic legs point to a future where prosthetic limbs will been seen as having more advantages than the ones made of flesh. They don’t tear, they don’t fatigue, they never get weak. In this future, limbs will not just be repaired, they will improve us. And make us think that the natural us are ‘disabled.’

3D printed body parts and other prosthetics allow for more creative construction of the body, for an altered topography of our own flesh. So maybe in the future the natural body will not be enough and there will be a huge market for human enhancement.

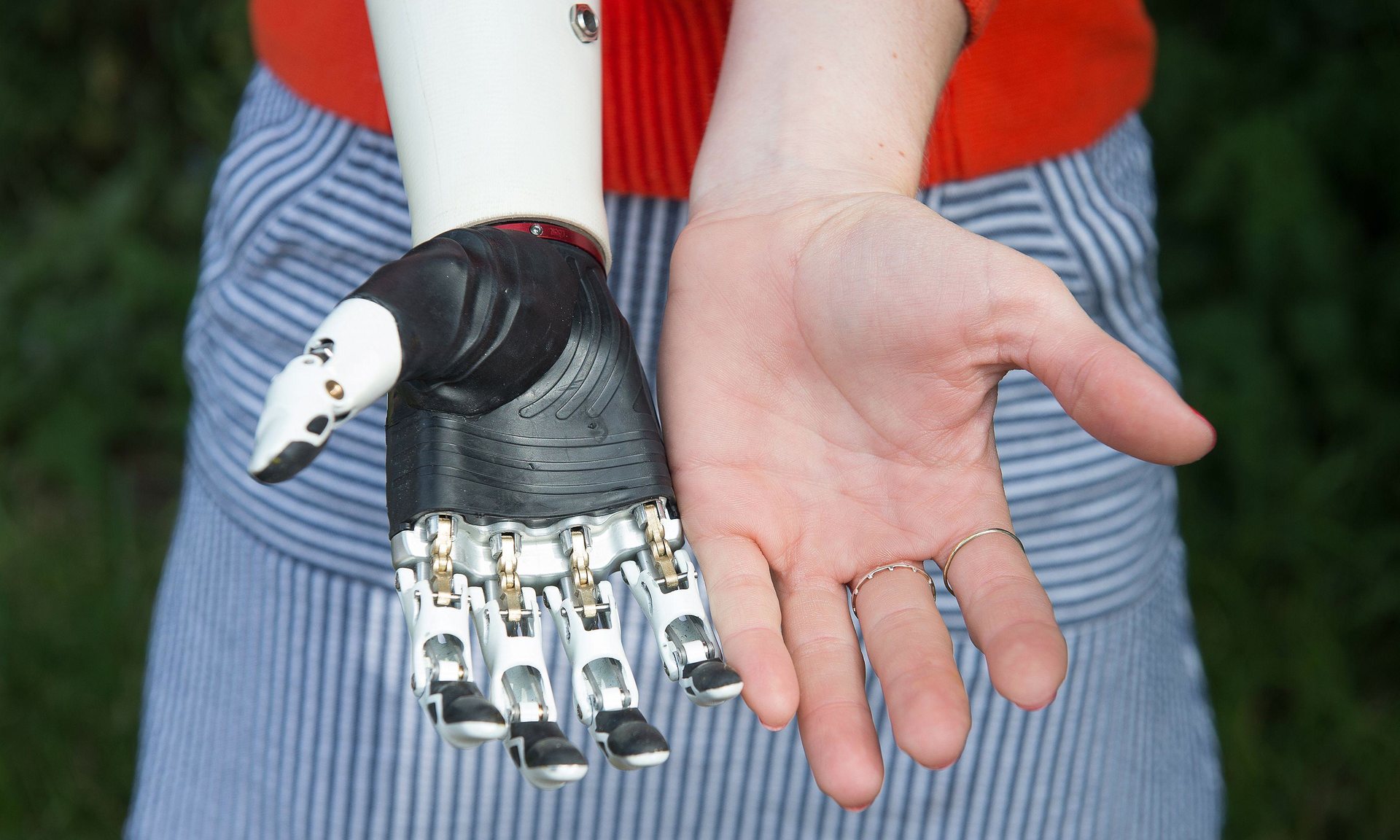

Nicky Ashwell with her anatomically accurate new hand. Photo: Laura Lean/PA, via The Guardian

And with that will come techno fetishists who are too fascinated by new technologies to take into account the daily reality of wearing prosthetic parts. Patients who have received bionic limbs, such as Nigel Ackland and Nicky Ashwell talk of the excitement of being able to enjoy all their limbs again but also of the real physical pain wearing them produces.

Don’t miss this other talk that Dr Laini Burton gave earlier this year in Brisbane, Australia:

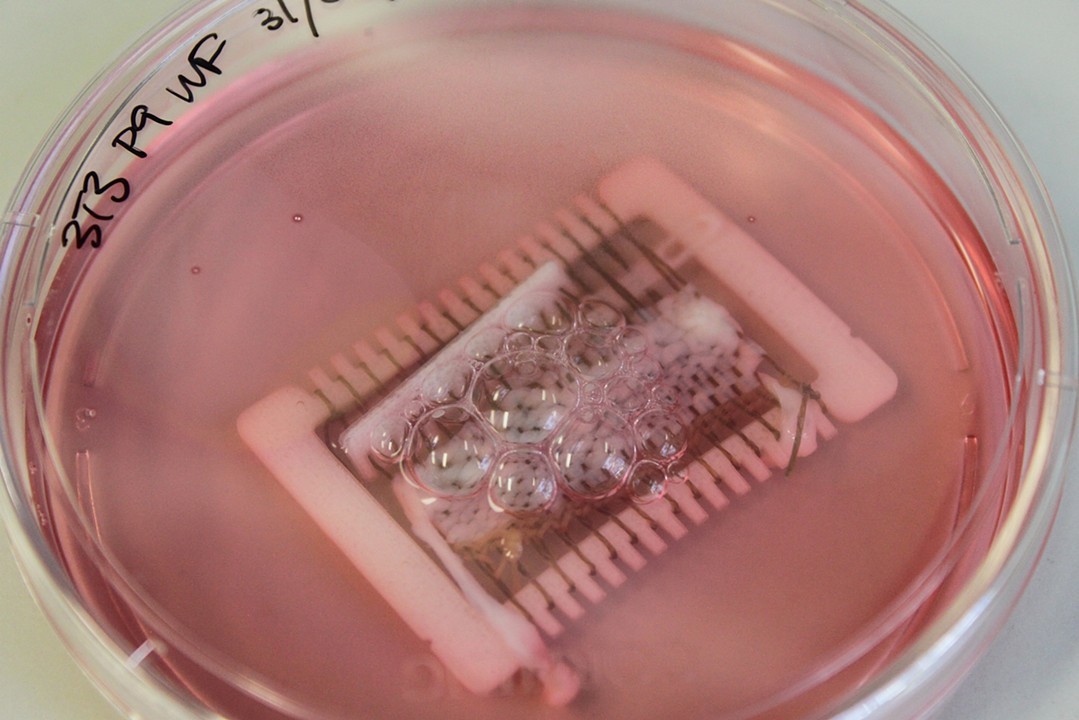

WhiteFeather Hunter, Crafting Biotextiles

The other talks of the day were:

Touch and Trace: Ethical methodologies for encountering Körper skin in critically reflective design practice by Dr. Tarryn Handcock (RMIT University, School of Fashion and Textiles.) She talked about The Anatomy Museum and The Dust Project, two works which look at dust and in particular dust made of human skin as a context for designing and wearing artefacts of dress, which is underpinned by the conceptual framework of a skin that wears.

In The witch in the lab coat: Conjuring flesh into mesh, artist WhiteFeather Hunter presented the works she developed during three years of laboratory-based residencies focusing on tissue culture. This work, situated within the framework of Feminist Materialism, analyzes the “craft” practice of tissue engineering as a form of haptic epistemology—that is, an embodied enactment/mimicry/redesign through creative and scientific means of the inherent haptic intelligence of the body and its biological systems of growth, repair and regeneration.