Marie Sester is a French media artist based in Los Angeles. She began her career as an architect, having earned her master’s degree from the Ecole d’Architecture in Strasbourg. Her interest, however, shifted from how to build living structures to how architecture and ideology affect our understanding of the world. Her work investigates the way a civilization originates and creates its forms. These forms are both tangible -such as signals, buildings, and cities- and intangible, such as the aspects of values, laws and culture.

Marie Sester is a French media artist based in Los Angeles. She began her career as an architect, having earned her master’s degree from the Ecole d’Architecture in Strasbourg. Her interest, however, shifted from how to build living structures to how architecture and ideology affect our understanding of the world. Her work investigates the way a civilization originates and creates its forms. These forms are both tangible -such as signals, buildings, and cities- and intangible, such as the aspects of values, laws and culture.

Quoting a profile of Sester written by Holly Willis: “What do these signs, these forms, these things that surround us mean?�? asks the artist. “What do they say about ideology? About capitalism? I realized after I finished my degree that I was interested in architectural forms on all levels, from the concrete elements such as city streets to ideological values, and how they evolve together.�? Marie Sester has received grants and residencies from the IAMAS, in Japan, Creative Capital Foundation, New York, Eyebeam, New York and many others. She has taught in France, Japan, and the United States and has exhibited internationally at SIGGRAPH, Ars Electronica (in the 2003 edition of the festival ACCESS received an Honorary Mention in Interactive Art), La Vilette, etc.

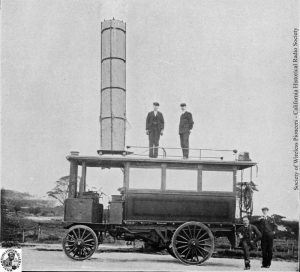

A few months ago, i was visiting the ZKM and i knew her work ACCESS was exhibited there. I had read what the work was about and was expecting to find it in the entrance lobby but i never suspected i’d be so startled and disturbed by it. ACCESS is a robotic spotlight and acoustic beam system that tracks individuals in public places. The beam is either activated as people move through the space under surveillance, or it is piloted remotely using a Web interface. While a friend of mine found the installation quite fun, I felt surprisingly guilty and isolated under that spotlight, exactly what i’d feel if i remembered that i’m under the gaze of surveillance cameras much about everytime i step out of my house. The experience taught me that i should never judge any interactive installation before having tested it myself.

BE[AM]

BE[AM]

You have a background in architecture, yet you’re working on interactive installations. How and when did you decide to focus on art installations?

I was trained in France in a six-year program, and although I was thinking of practicing, I quickly understood that I would not become a practicing architect. At that time, the school was a place where you could study within a broad range of possibilities, which was rare in France, because in France, you know exactly what you will get and there is no chance to change direction; you have to go through the plan described for you. But the school I attended was very open, and it was more about building an approach, a way of thinking, a mindset; it was about acquiring a state of mind.

My projects in school used data taken from the artworld, and were often rendered as paintings or engravings, and only the required technical drafts were architectural in the traditional sense. I remember with one presentation, when I finished, the members of the jury asked if they could get this piece or that piece from the project – I left the room with only my technical sheets under my arms!

Gradually I realized that I was more interested in the political and cultural ideology that underlies architecture, rather than in dealing with real clients and tons of steel and concrete. This, combined with my interest in art, led me to installation, which allowed me to be closer to my subject: to examine the way that a civilization originates and creates its forms, both tangible and intangible, and the way that political and ideological ideas become physical. Why are we surrounded by what we are surrounded with? And architecture is something our bodies and minds are changed by – in Japan, in a traditional house or temple, I feel differently, I breathe differently. It’s clear. And that is just one example. So these built spaces affect us enormously, and installation allows me to explore that.

Threatbox.us Preview at CalArts

Threatbox.us Preview at CalArts

Your work comments upon political transparency and invisibility, access, and surveillance. How much do you think the work of an artist can influence people’s views on these topics?

Instead of influence, art’s impact can rather disrupt, disturb, subvert, provoke, stimulate… Guy Debord uses the word “detournement,�? which I would freely translate to designate ways of destabilizing the predominant value-system. Art is more about asking questions than giving answers. My project Threatbox.us offers an example: The piece is meant to be installed in a public space, such as a train station, where there is a long wall and there are passersby. There is a projection of clips taken from a database of films, newscasts, computer games and so on, on the wall. The projection is slightly moving up, down, to the right, to the left, and people might think, “What is that? Why is it here? At a certain point however, the projector suddenly transforms into a spotlight which “attacks�? the body of one person, with a very loud, frightening noise. And for a moment, the person is under attack; the piece is very aggressive!

While it may not be immediately clear, the piece reflects on the way that our media has turned us into victims of propaganda, and it shows just how targeted we are, from radio to the Internet to the news to movies to games, everything! It’s non-stop and it’s very violent. It is something that I wanted to understand, and my piece is a way of provoking, of asking questions about the relationship between these images, violence and their impact on all of us.

We are driven by advertising, entertainment, gaming, fashion and war. War is now at the point to gain status of political correctness as a source of pride and consumption.

Culture is now a sub-product of politics. This isn’t really new – the difference with various past situations is that we are narrowing the span of infinite wonder of the universe and of our lives. The magic has disappeared from the world. Erased. For sure, magic is not transparent! Neither are the notions of instinct or intuition. Nevertheless, when something blows your mind, it can change the way you look at the world, and open it up to meditation and contemplation, and finally to being more aware. This is what an artwork can do; it creates a distance between the common place and the inner space, and lets people think by themselves. One might call this self-awareness.

So, my method is really to introduce subversive elements into the system, with grace and humor. And always to push further the questions and the proposals.

Many political activists and artists believe that instead of creating a feeling of security, surveillance systems make us feel like suspects. A friend of mine told me about an interaction designer who had devised a way for people living in a London to avoid the gaze of the CCTV network. But it turned out that people were not happy with the idea, they actually liked to be on surveillance camera. What’s your take on this?

Cameras are only the most visible means of surveillance. At first view, most people have nothing to hide. So there is no problem being under surveillance. Also, television, soap operas and reality shows present surveillance as desirable, and I know there are people – like with JennyCam and other webcam projects – who like the performing and being watched. I don’t really understand this. If we’re all performing, or playing, then – and please excuse this expression – we don’t give a shit.

I think it’s more serious. It has to do with our autonomy, our lives, our commitment. We are so manipulated that we cannot make a commitment, and that affects our being part of the universe.

We all know that surveillance is a control tool. And it’s best done when it is invisible. It’s quite fascinating how far the military and other government agencies go in this domain. It becomes seriously scary, whatever way you look at it.

ACCESS

ACCESS

ACCESS has been showed in several countries. Did you have the chance to cross-reference the various reactions that emerged in each location? How do people behave under the ACCESS beam? And can you imagine ACCESS being installed in a public place, not a museum nor an art gallery?

With ACCESS, some people run away in fear, and other people really enjoy it and want to stay in the spotlight and play. And I would love for ACCESS to be shown outside a museum or gallery. It is a permanent installation at ZKM [Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie] in Karlsruhe, Germany. So, it is the first contact you have with this museum, before you even reach the information desk. But it’s still inside the museum where you are prepared for an art experience. What would happen in a public space without that set up? The first public test was done in Japan, in a corporate lobby, and the reactions of the unsuspecting public was significantly different. That’s what I would really like, to put ACCESS in places like that. It was the very concept of ACCESS.

What is the impetus behind the Threatbox.us project?

Exasperation with all the noise and hype, plus the cruelty, and the violent and destructive politics of the current (and not so new) state strategy: “the industrial – entertainment – military complex.�? They are non-sense noises, if not crimes against the universe. And even fantasy worlds look dark. It seems that light (and lightness) has all but been erased.

But here is how the project took shape: When I was younger, I watched a lot of movies by great filmmakers. This was in the ’70s and ’80s, and included filmmakers like Pasolini, Fellini, Godard of course, great filmmakers. But at a certain point, I realized I couldn’t watch any more movies, especially American movies. I found them invasive, mind-invasive. So I stopped, for 25 years! And then, recently I realized that we were living in a world increasingly filled with aggression, and I wanted to understand it, and why this aggression is so prevalent. So I talked with several people, including my friend McKenzie Wark (who wrote The Hacker Manifesto) and then started watching movies again, asking, “What’s going on here?�? I watched them on my computer, as DVDs, so I could stop when I needed to, so that I could really study the films. I collected a database of clips, and at a certain point I realized I could go in two directions with the material.

One direction was to think about all the aggression, and another was to think about how to deal with these ideas. This second direction became BE[AM], which uses this database of American pop culture, but we see it through these three guys who are the opposite of what we are led to believe is the strong male, the warriors and killers, violent and destructive. These three guys – Charlie Chaplin, Wile E. Coyote and Super Mario – are struggling like us, with the world, and the idea that at any moment you can get into trouble, but we have to just go through it. These guys are always in trouble, but they always come back, they find ways, and they start from scratch again and again and again. So BE[AM] looks at these images, and lets you enter them in a game that, also, is not typical; rather than trying to win or achieve a goal, there is nothing to win!

The other direction, of course, is Threatbox.us, which also uses a database of images, but is much more aggressive and violent, with the attack of the robotic projector beam and the sense that you have been targeted. So this begins to question the merging of vision and destruction, of the aggression of entertainment industry and of the military…

You are French but live in California. Are the States a more fertile territory for new media art works? How do you find the new media artscene there? How much has your life there influenced your work?

In Paris I was very busy, with many shows and I had a very strong practice for years and years. When I came to the US, I did not find the same support, but I found other kinds of networks. During my 2 years in New York I was lucky having the support of Creative Capital Foundation, a residency at Eyebeam, and grants from Franklin Furnace Fund, NYSCA, and LEF. And Los Angeles? The first two days I was here, I was ready to buy a ticket back to New York! But after a few days, I adjusted. LA has great weather, flowers, birds, landscapes. Living here is a real pleasure. Nevertheless, I miss New York in the sense that there, direct encounters and confrontations are easy and energizing. I was happy collaborating with McKenzie Wark, for example, and I enjoyed working closely with other people, having long discussions, particularly with the NYU ITP community. I don’t find that here. Maybe I am not looking, but it is very hard to stay connected. I can stay very connected online, but not with people. In New York, you see people everywhere; it is not true here. Where are the artists I like? Are we all isolated?

For me, LA is interesting on another level, and it’s big: the city obliges you to reinvent yourself. The New Yorker or European logic doesn’t work here….

Any designers, artists or architects whose work you find particularly meaningful?

The Yes Men (Andy Bichlbaum) for sure!

What are the projects you are working on now?

ACCESS will appear next in Luxembourg, then at the Whitney in NY. I am continuing to work on BE[AM] and Threatbox.us for final tests. I have also started a smaller size project to become a multiple in the spirit of my larger scale installations.

Thanks Marie.

With special thanks from Marie Sester to Holly Willis for editorial assistance; to McKenzie Wark for his generous collaboration, helping to constitute the American pop culture media data base, with advisory by Carl Goodman, Director of programs at the Museum of the Moving Image, NY.

Portrait of Marie Sester photo-composited by Michael Naimark, 2006.