Lambeth Towers. © Utopia London

Lambeth Towers. © Utopia London

Yesterday i watched a copy of Utopia London, a documentary directed by Tom Cordell. My notes come right after the press blurb:

The film observes the method and practice of the Modernist architects who rebuilt London after World War Two. It shows how they revolutionised life in the city in the wake of destruction from war and the poor living conditions inherited from the Industrial Revolution. This film is their story. Utopia London travels through the recent history of the city where the film maker grew up. He finds the architects who designed it and reunites them with the buildings they created.

These young idealists were once united around a vision of using science and art to create a city of equal citizens. Their architecture fused William Morris with urban high-rise; ancient parkland with concrete.

Utopia London examines the, social and political agendas of the time in which the city was rebuilt. The story goes on to explore how the meaning of these transformative buildings has been radically manipulated over subsequent decades. Inspired by the optimism of the past it poses the question; where do we go from here and now?

Utopia London documentary trailer

The documentary goes through the history of a dozen modernist buildings. The objective is not to brush a history of architecture in London but to remind us of a British society that had faith in social utopian ideology. The first comments and images of the film look at a panorama of London at a time when the city was built for God. Nowadays, the London skyline evokes finance. The Modernist movement broke the timeline that went from churches to banks with a series of architectural landmarks designed to achieve social good, not through charity, but by the hands of both socially-conscious architects and an accountable municipal authority.

Finsbury Health Centre (image e-architect)

Finsbury Health Centre (image e-architect)

The first construction we’re introduced to is the Finsbury Health Centre, designed by Berthold Lubetkin and completed in 1938. Lubetkin was a Russian émigré, he brought with him the dogma of Soviet socialist thinking and revolutionary Constructivist design. The center is a landmark of the early Modern Movement in Britain. It was designed to be adaptable to the ever evolving requirements of healthcare. The centre also had a preventive mission, encouraging people to live healthier lives in a light, airy environment. A solarium gave the children (who spent much of their days in thick smog) a chance to feel the benefits of sunlight.

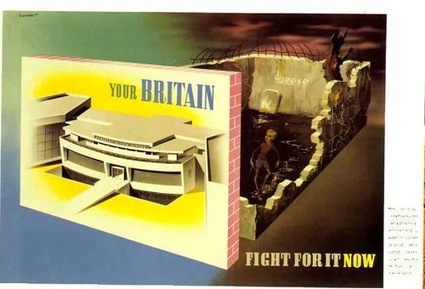

War time poster by Abram Games, 1942. Credits Imperial War Museum. Accompanying text: ‘Modern medicine means the maintenance of good health and prevention and early detection of diseases. This is achieved by periodic medical examination at Centres such as the new Finsbury Health Centre, where modern methods are used’

War time poster by Abram Games, 1942. Credits Imperial War Museum. Accompanying text: ‘Modern medicine means the maintenance of good health and prevention and early detection of diseases. This is achieved by periodic medical examination at Centres such as the new Finsbury Health Centre, where modern methods are used’

The Second World War broke soon after the opening of Finsbury Health Centre. As the poster above shows, the health center became a beacon for hope rising from what used to be London slums. Unfortunately, its icon status, radical architecture and social commitment don’t seem to be enough to impress today’s authorities.

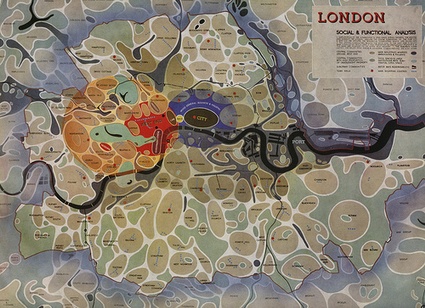

Abercrombie/Forshaw’s London Community map, 1942

Abercrombie/Forshaw’s London Community map, 1942

War bombings had destroyed hundreds of thousands of dwellings, leaving almost one and a half million people homeless. After the war, town planning academic Patrick Abercrombie and architect John Forshaw were hired to design the future London. They dreamed up urban spaces where the various classes of London’s society would meet and mingle. The South Bank was at the heart of their egalitarian plans, they hoped it would provide a shared space for all Londoners to spend their free time and enjoy art and culture.

The Hayward Gallery. © Utopia London

The Hayward Gallery. © Utopia London

The sequences about council estates were probably the most enlightening for me. I know of council estates through Shameless, British tv crime fictions or just the crime pages of Brit newspapers. They evoked little more than dysfunctionality and bleakness to me. Yet, they were built with the best intentions. “We wanted to build Heaven on Earth” declared architect Oliver Cox who was part of the team that built Alton East. Indeed, when the camera follows the architects inside the apartments or eavesdrops on their conversations with the residents, life looks almost cheerful in a council estate. They were designed with plenty of space, nice views overlooking the city, green and recreational areas. They were built in a time of optimism and faith in what the future would bring to society.

Still from Fahrenheit 451, a 1966 film by François Truffaut

Still from Fahrenheit 451, a 1966 film by François Truffaut

The concrete that used to stand for progress and modernity quickly became a symbol of the welfare state. Even worse it came to emblematize Britain’s continued class division. The film exemplifies Modernism’s fall from grace by reminding us that Truffaut’s 1966 film Fahrenheit 451 takes place amidst Modernist buildings, in particular the Alton housing estate in Roehampton, South London. The movie is set in a dystopian future where the main role of firemen is to burn all books. Modernist architecture is used in the movie to carry a sense of uniformity, not humanity.

Interviewing Neave Brown at the Alexandra Road Estate. © Utopia London

Interviewing Neave Brown at the Alexandra Road Estate. © Utopia London

In the ’70s, big social housing schemes were scrapped. In the ’80s, dreams of a brighter, more egalitarian future were eclipsed by Margaret Thatcher’s politics which saw market forces as the main makers and shapers of society. Among Thatcher’s advisors was Prof. Alice Coleman who blamed post-war social housing developments for ‘social malaise’. Her team paralleled the amount of litter, vandalism, graffiti, the presence of excrement, etc. with design features such as number of storeys, number of entrances and flats in a block etc. to suggest that the architecture of council estates turned their residents into criminals. The findings published in 1985 under the name Utopia on trial were controversial, let alone because the study ignored the impact of poverty.

Today, despite their striking volumes and place in the history of architecture, Modernist and Brutalist buildings remain unloved. Pimlico School has disappeared and Robin Hood Gardens might meet the same fate. Even when a Grade II listing is granted, the building could still face demolition. Grade II listings can be ignored on the grounds of the economic or social benefit of redevelopment.

Director Tom Cordell. © Utopia London

Director Tom Cordell. © Utopia London

Utopia London takes a very clear stand, one in favour of the respect and preservation of buildings erected in a time of utopia and hope. From the beautiful shots of the buildings at night to the very moving walks that the architects take in the buildings they designed, one feels the same twinge of envy that the documentary director confesses for a time when society believed that good design and planning could lead to a brighter future.

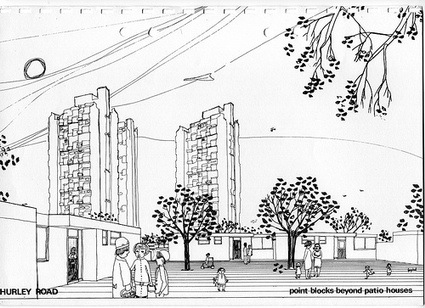

Architect George Finch’s drawing of Cotton Gardens Estate, 1966

Architect George Finch’s drawing of Cotton Gardens Estate, 1966

Despite my admiration for Brutalism and socially embedded architecture, i sometimes wished that Cordell had given more space for its detractors to express their views. Utopia London would still have been a very moving film. It is a documentary for Londoners and also for tourists whose love for London goes beyond Portobello market and the Tate turbine hall. Its attention to details charmed me right from the start: the opening sequence has elegant, clean infographics; the text is catchy; archive materials provide moments of irony and humour (did i recognize an extract from Zéro de Conduite?), etc. The accent of the director as he does the voice-over was particularly well-suited, it screamed ‘London!’ clearer than any beefeater or Piccadilly Circus could do. But best of all, the documentary – just like the architecture it champions- focuses on people. Meeting the architects who had designed the buildings was a rare treat. So was hearing the confidence of Prof. Alice Coleman 25 years after her study condemned Modernist social housing. And then there were briefs moments with Dorrit Dekk. Can anyone not fall in love with Dorrit Dekk?

Dawsons Heights. © Utopia London

Dawsons Heights. © Utopia London

Image on the homepage: Alton East Estate. © Utopia London.

More extracts from the documentary.

This way to buy the DVD.

Related: Book review: Goodbye to London – Radical Art and Politics in the Seventies.