Utopia & Contemporary Art, edited by Christian Gether, Stine Høholt and Marie Laurberg. (available on amazon UK and USA.)

Publisher Hatje Cantz writes: Utopia has become a controversial concept, spanning the field between the belief in an ideal society and the dystopian nightmare. Within the last decade, the contemporary art scene has witnessed a return of utopia and utopian thinking. Whether detectable as an impulse, critically reassessed as a concept, or cautiously or daringly articulated in a specific vision–utopia continues to matter. This publication investigates the meanings of utopia in contemporary art. Theorists, critics, and curators discuss the different ways of thinking and performing utopia in contemporary art from a broad range of angles. The essays explore the current relevance of utopia as well as how people in different societies live, think, act, and imagine.

The two parts, Utopia Revisited and Utopian Positions, provide both a theoretical backdrop for the reformulations of utopia in contemporary art as well as examinations of specific utopian stances in connection with the three-year utopia project at ARKEN Museum of Modern Art and solo shows by Qiu Anxiong, Katharina Grosse, and Olafur Eliasson.

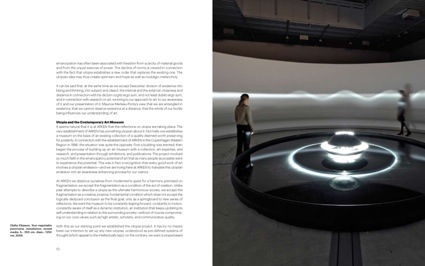

Olafur Eliasson, Din blinde Passager (Your Blind Passenger), 2010. Photo: Studio Olafur Eliasson

Olafur Eliasson, Din blinde Passager (Your Blind Passenger), 2010. Photo: Studio Olafur Eliasson

Utopia & Contemporary Art is a collection of essays by curators, art critics, academics and art historians who explore the meaning and place that the concept of utopia has taken in art. The first part “Utopia Revisited” illustrates the resurgence of utopia in contemporary art. Although utopia as a governmental precept has fallen from grace after a series of misguided attempts to put it into practice in the 20th century, the art world is now welcoming the concept back into its critical discourse. Utopia as a mode of thinking can inspire us to take a break from reality and think beyond what is already existing. ‘Utopian’ artworks do not necessarily require from us to take their ideas literally. Their objective is rather to elicit a moment of reflexion and inner questioning “to which extent could the art proposal work?” “how does it compare to the world i live in?” etc.

Because the book is a collection of essays about the topic, there are some repetitions in the Utopia Revisited part, with most authors feeling they have to remind us of Thomas More. Each text, however, bring a different outlook and perspective on utopia in art.

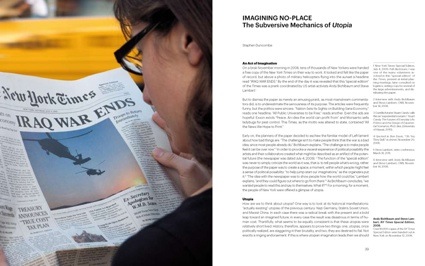

View inside the book

View inside the book

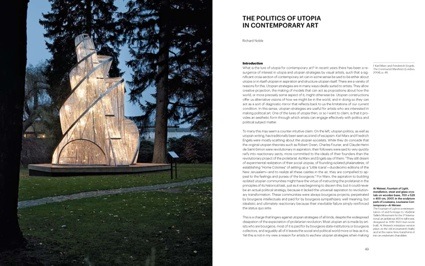

Richard Noble‘s contribution kept on bringing issues that are otherwise often ignored by enthusiastic artists, curators and critics: how most utopian art is made by artists from bourgeois background, paid for by rich collectors or state institutions and how it has virtually no impact on society nor the political world. How difficult it is to make a political work or art that is effective as an artwork or as a political act or both. Or how to distinguish between an utopian artwork from a political artwork. How the impact of a political artwork is influenced by the context (Noble gave the example of the reason behind Ai Weiwei‘s arrest for tax evasion: a project that involved displaying publicly the list of the names and ages of the victims of the Szechuan earthquake, an information that Chines authorities had suppressed.)

Another essay worth mentioning is the one by Jacob Wamberg in which he maps the utopian tendencies of modern art movements depending on whether they are located in ‘virtual’ space (the one of autonomous consciousness, think Kandinsky), the ‘real’ space (the one that directly engages with architecture and design, think Bauhaus) or in between (in the social sphere, think Situationism, Fluxus, Dada, etc.)

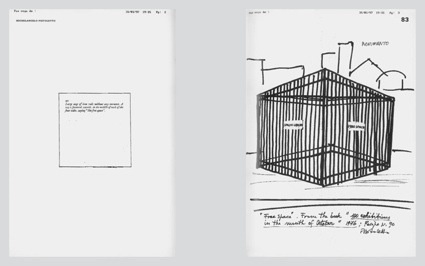

View inside the book. Unrealized Art Projects

View inside the book. Unrealized Art Projects

The second part of the book, Artists Projects, is pure joy. It opens with a selection of Unrealized Art Projects that Hans Ulrich-Obrist has been collecting since 1990. He has amassed thousands of texts, drawings, and correspondence that documents projects which, for some reason, never saw the light of the day.

Things get even better in the third and last part of the book, Utopian Positions. In The Claim for New Territories, Ildiko Dao and Simon Lamunière, look at communities founded by artists. From Yoko Ono and John Lennon’s Nutopia to micro-nations, to a borderless city built on Second Life, up to the more viable The Land, a self-sustaining and transdisciplinary project created by Rirkrit Tiravanija and Kamin Letchaiprasert.

Cao Fei , Whose Utopia, 2006

Cao Fei , Whose Utopia, 2006

Ilya Kabakov, The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment, 1988

Ilya Kabakov, The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment, 1988

And perhaps because each culture has its own idea (or perhaps experience) of what constitutes an utopia, the final essays examine artists’ utopian projects in different territories: Rachel Weiss considers the form and role of utopia in Cuban art, Inke Arns gives a tour the Utopian in Eastern Europe, and Hou Hanru explores the Chinese contemporary artists’ reaction to the rise of the consumerist society in their country.

In the background: Battery house by Francois Roche and Philippe Parreno, at The Land Foundation, Thailand, launched by Rirkrit Tiravanija and Kamin Letchaiprasert, 1998-

In the background: Battery house by Francois Roche and Philippe Parreno, at The Land Foundation, Thailand, launched by Rirkrit Tiravanija and Kamin Letchaiprasert, 1998-

Views inside the book: