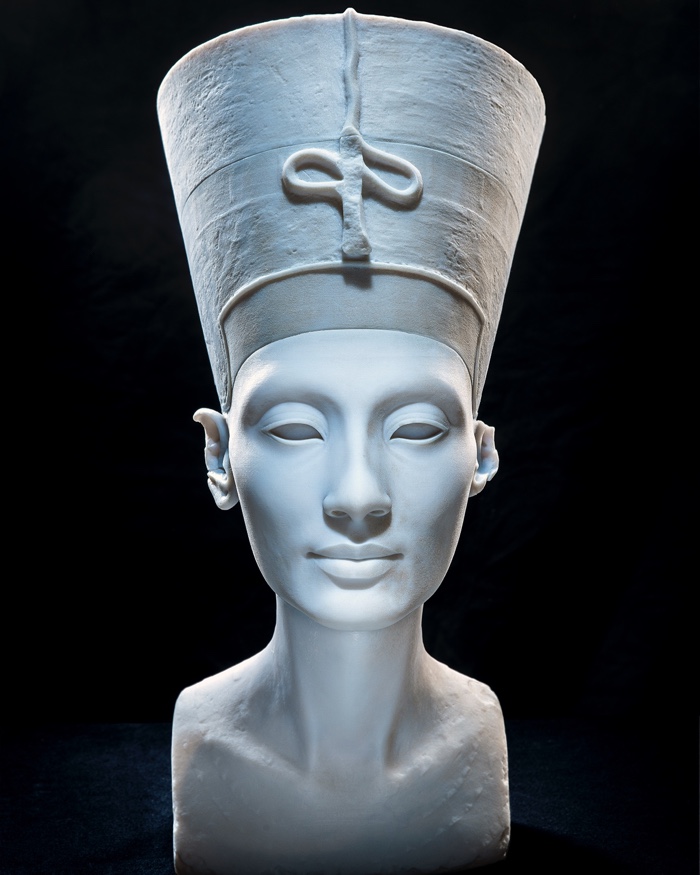

For years, Egypt has been trying to convince European museums to return Egyptian antiquities that left their country illegally. One of the most famous disputed artifact is the bust of 14th-century BCE Egyptian queen Nefertiti. German archaeologists took it from the African country in 1912 and their country has since repeatedly denied loan requests from Egypt’s cultural institutions. The debate around the growing list of disputed museum treasures is one that most Europeans would rather not think about. Once in a while however, a scandal, a protest, a movie or a contemporary artwork forces ex-colonising countries to confront the firm grip that their institutions maintain on access to knowledge and on the global narratives of history.

Nora Al-Badri and Nikolai Nelles, The Other Nefertiti, 2015

Nora Al-Badri and Nikolai Nelles, Fossil Futures, 2017

In early 2016, artists Nora Al-Badri and Nikolai Nelles announced that they had illegally scanned the Nefertiti head at Neues Museum in Berlin, they also made a copy of the bust and released the 3D data. Their “Nefertiti Hack” became the centre of heated discussions about ownership, authenticity, cultural identity and power imbalances.

A couple of years later, the artists turned their attention to another icon of Berlin cultural life: Oskar, the world’s largest assembled dinosaur skeleton. This Brachiosaurus brancai lived nearly 150 million years old ago. Al-Badri and Nelles tracked its origins to the south of Tanzania. Discovered by German archaeologists when Tanzania was still under colonial rule, the petrified bones were shipped to Germany, assembled and are now the main stars of Berlin’s Museum of Natural History. The artistic investigation culminated in Fossil Future, a series of works that further examine the enduring consequences and legacies of colonial power.

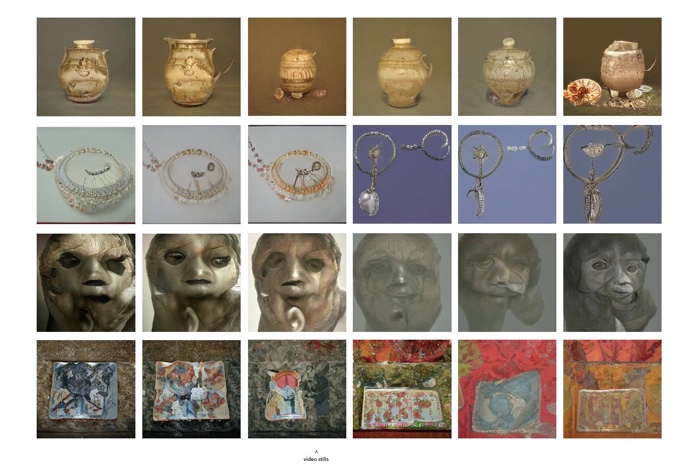

Nora Al-Badri, Babylonian Vision, 2020

Nora Al-Badri‘s most recent research projects apply GANs to images of archaeological artifacts in order to continue her questioning of the institutional power structures of Western museums. What make her works -and the one she has developed in collaboration with Nikolai Nelles– so compelling is that they go beyond confronting the audience with uncomfortable ethical questions about the full history of museum collections. They also present new platforms for public discussions, new counter-narratives and new emancipatory strategies to examine issues of decolonisation.

Nora Al-Badri is a multi-disciplinary media artist with a German-Iraqi background. She lives and works in Berlin. She graduated in political sciences at Johann Wolfgang Goethe University in Frankfurt / Main. We talked over a Skype video call:

Nora Al-Badri, Babylonian Vision, 2020

Nora Al-Badri, Babylonian Vision training, 2020

Hi Nora! Let’s start with Babylonian Vision, a work you’ve developed as the first artist in residency at the Institute for Technology in Lausanne (EPFL) and its Laboratory for Experimental Museology (eM+) led by Sarah Kenderdine.

In the description of the work, you say that you contacted the five museums that have the largest collections of Mesopotamian, Neo-Sumerian and Assyrian artefacts and they didn’t give you the authorisation. Did they actually answer you and motivate their refusal?

Some of them responded. Some have their formal channels through which researchers or journalists can make requests for their datasets or get information about the artefacts but usually, the response was that it would cost some money and that for each object you want to access, you would have to sign one page and describe the reason for your request. I needed 10 000 objects which made it unmanageable. Through these bureaucratic obstacles, these institutions are also gaining control over the objects.

Why 10 000? Did you already know there were so many digitised artefacts in these collections or was it that you needed the critical mass for the technology?

We needed critical mass to train a neural network from scratch. There are millions of objects even though not all of them have been digitised yet. In the end, I was glad that somehow the institutions do not realise that some parts of their database is actually available online. One person cannot download all these objects one by one but the process can be automated and that’s what we did. That was the web-crawling part of the project.

One of the most important thing to me when I was thinking about training data sets is the problem of the AI as a black box system that makes it impossible to trace back the dataset used. You just don’t know where the input data came from.

Ironically, this black box problem can now be used against the museum, against the colonial machine. We more or less know who/where the largest collections in the world are but they cannot prove that I used their datasets to train the system. In many instances, the black box aspect of AI can be a problem but in some cases, it can also be liberating.

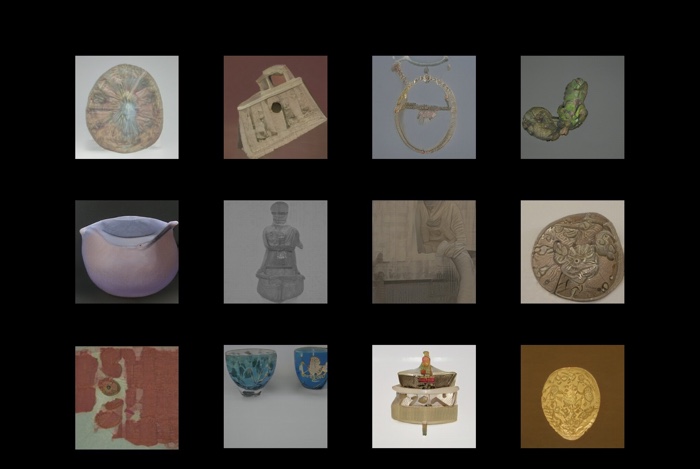

Nora Al-Badri, Neuronal Ancestral Sculptures Series

Can you explain this idea of the technoheritage? Why was it an important concept to explore?

I started to use that term many years ago when museums began to digitise large amounts of their collections and then created what they described as “digital assets” or “digital artefacts”. In fact a law researcher, Sonia K. Katyal who wrote about another project of mine, did name her article about 3D printing and intellectual copyrights “Technoheritage”. I wondered what the term really meant, if it was just a formulation or something that was independent of the physical object that could be translated, mediated, used and remixed all over the place. In a way, for me, it was a separate entity and I used the term technoheritage to describe it. Heritage is a term that looks into the past but to me, technoheritage is not looking at the past at all. Instead, it is looking towards another scenario of the future. And rather than preserving something, it can offer a new contribution and be used as a starting point for artistic research, for remixing and even updating the object.

The Neuronal Ancestral Sculptures Series also explores the technoheritage. Everything we come up with as artists is not 100% new and original, it builds on what was done before and it cannot be totally isolated from its context. The series is meant to honour works produced thousands of years ago. We still have sculptures similar to those today.

The Neuronal Ancestral Sculptures Series is more or less about the image that comes out of it, it is a concrete as well as synthetic image, like a still image of an object that is the sculpture. Babylonian Vision, on the other hand, is about the process of the machine vision through the Babylonian lens, looking at the patterns and forms of a specific time and era.

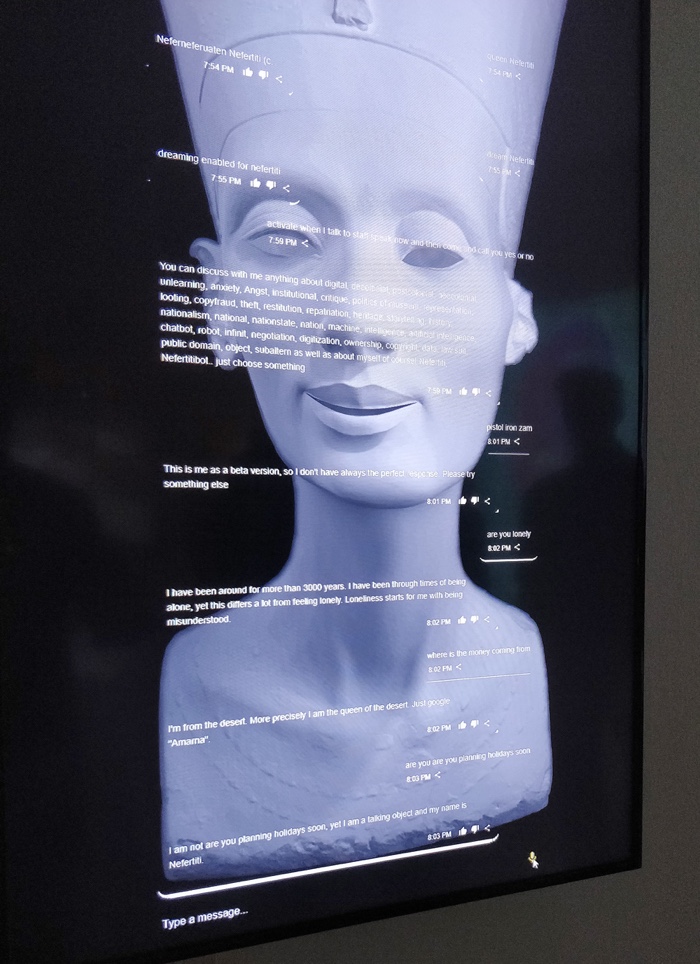

BBC Newsnight, #NefertitiHack with Nora Al-Badri

Nora Al-Badri and Nikolai Nelles, NefertitiBot, 2018

Queen Margrethe II of Denmark views the bust of 3,400-year-old Queen Nefertiti, Berlin, 2014. Photo by Andreas Rentz/Getty Images via al-monitor

The NefertitiBot also looks at topics of appropriation, at how the Global North museums and institutions are monopolising the imagery of ancient artefacts. Why did you delegate that difficult conversation to a bot, to a product of technology?

The Bot was an experiment that deals with the computer-human interface. We live in a time when people delegate many things to computers and believe in the results of algorithms. We played with that myth of technology. Personally, as an artist, I wouldn’t delegate the discussions to an automated process but I think that through the interaction with an automated process, we can see more clearly how we, as humans, should learn to be more critical. Automation is not magic. We wanted to expose those kinds of questions to the audience and actually, we were surprised at how critical the Nefertiti Bot was. Of course, the Bot is packed with biases but they are my biases, they are decolonial biases so they are on the opposite side of the usual biases. As artists, we can work with the shortcomings of technology and turn them completely around.

Nora Al-Badri and Nikolai Nelles, ‘NOT A SINGLE BONE’ exhibition at Nome Gallery, Berlin, 2017

Let’s talk about Fossil Futures. It’s always been clear how some cultural artefacts were stolen, appropriated by European and U.S. museums but we tend not to think in appropriation terms when it comes to dinosaurs bones, plants or anything you can find in a Natural History Museum. How did you get involved in this Tanzanian project?

It started a bit as the Nefertiti Bot started. Both Nefertiti and the dinosaur bones are museum centrepieces here in Berlin. That made us want to look closer. Before working on this project, I had no idea that the dinosaur was from Tanzania and that it had come through a large colonial expedition when not just the bones but many other resources were extracted. Many people where probably dislocated as well. If you look closer you will find many stories about objects, plants that have similarly been displaced and appropriated.

Nora Al-Badri and Nikolai Nelles, Territories of Cultural Fracking (videostill), 2017

Nora Al-Badri and Nikolai Nelles, Territories of Cultural Fracking (videostill), 2017

In an interview you did with Berlin Art Link in 2017 you talk about this plan to create a natural forest reserve instead of a museum. You were talking about “counter land-grabbing”. Do you keep in touch with the Tendaguru community and do you know what happened to this project of a forest reserve? /

We did several installations but what we never realised was how difficult it would be to fund the project, especially when we are talking about a project that criticises the people who should actually fund you. This was a failure that could have been anticipated.

We never got to realise the second part of the project which was for me the more important one and that involved installing that natural forest reserve. We were more or less the first people from Germany to go there and ask the community what they actually wanted and who they were. They wanted to set up their own museum, with their own narrative about the site. For them, it is still a sacred site that contains many more stories than the ones told here at the National Museum of Natural History. It ended up becoming a public debate here with the Natural History Museum and in the newspapers that became personal. And maybe I should quote one of the peculiar criticisms one of their historians had: he was enraged and stunned that we dared to speak to the people because we were no legitimate scientists like ethnographer or historians. As a matter of fact, just none of them ever dared to speak to the Tendaguru community.. Unfortunately, the museum managed to shut us down. We were only two artists and we only have so much power.

I’m also wondering about the discussions around the colonial past of Germany. Is it happening?

After the Nefertiti hack, it was a good moment in a way but from then on, the discussion evolved more and more into a broader public debate. Yet, I’m surprised to see how slow-moving the museums are, how conservatively-governed they are. There is a lot of money poured into that kind of research on the colonial past of collections for example. That is great but that research often stays in its ivory tower and hasn’t changed the fundamental nature of the collection. However, I remain optimistic that with more time, more intervention and more pressure from movements such as Rhodes Must Fall and Black Lives Matter as well as from other sides of society the situation will improve.

It is already changing of course but it’s still a bit too hesitant. When we think about decolonising institutions, be it a university or a museum, then the change will only happen through structural change. You can see for example how some people of colour are now invited to take part in discussions but I haven’t seen so many people of colour put in high positions where they can actually bring significant changes.

Nora Al-Badri and Jan Nikolai Nelles, Robo Polke, 2018

Nora Al-Badri and Jan Nikolai Nelles, Robo Polke, 2018

Another work you did with Jan Nikolai Nelles is Robo Polke, an industrial robot that is reproducing one of Pollock’s paintings. The work is a comment on machine non-creativity. How do you react to all the newspapers/magazines headlines that talk about AI becoming more creative, making music, films, paintings and is stealing the work of creative people?

Usually, when there’s so much hype around it, you realise that there isn’t so much to it. I’m not afraid of the creativity of the machine because I don’t believe that a machine can reproduce anything close to the idea of a soul or of human irrationality. It is true that machines can do extraordinary things. Now with the deep fake technology, we can automate nasty jobs such as the ones done by people in the advertisement. Soon we won’t need real people anymore: we will just need a database of people faces, bodies and movement.

But some people are afraid of losing even awful jobs to robots….

I believe these anxieties are giving society an opportunity to rethink what labour means. There will be many jobs that we cannot shift to machines. In particular, jobs that require compassion and empathy. Taking care of children or of the elderly, for example. This is a question for policy-making and the people, it’s about how right now we identify ourselves only through our work and how society perceives us based on the work we do. Maybe we need to reinvent our identities and rethink what makes us valuable. Hannah Arendt pointed that out some time ago in “Vita activa”.

Is there any upcoming work, event or field of research you’d like to share with us?

In January the exhibition Babylonian Vision will open in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Right now, I’m also doing some research on the question of the representation in datasets of the Global North vs the Global South. Today, even poorer households are not well represented in training datasets of big GAN. It might actually be an advantage in times of surveillance. The rich and the middle-class kind of surveil themselves. The downside, however, is the production of visual and geographical hegemony. I thought I could explore this aspect. When I do my Babylonian datasets this is already something for me that decolonial act because those objects, the ideas of the people of the time are not yet represented in any form of training data.

Scientific research papers are now being published that show that awareness of the problem is growing. But what does it mean if the poorer parts of society and the Global South are not protected? A lot of data is extracted from them but they don’t have the type of data privacy we have in Europe.

I also have a website-based project for Kunst-Werke in Berlin for this spring that deals with the feminine in hackerspaces. Artists from every continent are working on it as a virtual group show that will also be located in physical space.

Thanks Nora!