You often read that the future belongs to Africa. If you think that future equals Western technological ideas of progress and you are a fairly pragmatic observer then indeed Africa is the future. The minerals we need to build tomorrow’s green and techno-powered lifestyle are located beneath its soil. It is also the continent where Western companies expect to find massive market growth and cheap labour.

The uncompleted campus library of the University of African Future. Photo: Hamedine Kane & Stéphane Verlet-Bottéro, via

Hamedine Kane, Stéphane Verlet-Bottéro and Nathalie Muchamad with Olivia Anani and Lou Mo, The School of Mutants (still image), 2020

But are there other definitions of the future? Other ways to envision the future(s)? The exhibition UFA – Université des Futurs Africains (or University of African Futures) presents the work of artists who go back in time to deconstruct clichés about Africa’s relationship to the future and who summon the mythologies of origins to invent alternatives.

Each in their own way, the invited artists combine the examination of local traditions, technology, ancient knowledge and science to delve into the place that Africa played in the imagination of the future and to speculate on how the continent can shape its own narratives, free itself from dominant models and develop its own vision of the future(s.) Maybe, I’d like to add, maybe the rest of the world could learn something from these investigations and reflections.

The artists in the show can be regarded as HistoFuturists. Science fiction writer Octavia E. Butler called HistoFuturist “someone who looks forward without turning his or her back on the past, combining an interest in the human factor and in technology.” This interweaving between the past, the present and the future is also echoed in Felwine Sarr‘s notion of “active utopia.” In his book Afrotopia, the philosopher and economist advocates a break from inadequate development models (often devised outside of the continent) and calls for an archeology of local cultures, so that Africa can move forward and develop its “own metaphors of the future” and its own strategies to connect with the rest of humanity.

Larry Achiampong, Pan African Flag for the relic travellers’ alliance, 2017-2018

Nolan Oswald Dennis, Black Liberation Zodiac (BLZ) the 12th house: toward a black planetarium, 2017-2021

Russel Hlongwane, Ifu Elimnyama: The Dark Cloud, 2019. Installation view at Le Lieu Unique. Photo: David Gallard

Russel Hlongwane, Ifu Elimnyama: The Dark Cloud, 2019. Installation view at Le Lieu Unique. Photo: David Gallard

As for the intriguing title of the exhibition, it refers to the University of the African Future (UFA) in Sébikotane, Senegal, an ambitious project initiated by President Abdoulaye Wade in the mid-2000s and now abandoned. The exhibition turns the failed education project into an inquiry into more dynamic models of education and a call to reinvent the idea of the university.

The exhibition should open at Le Lieu Unique in Nantes (a port city that played an active role in the trade of enslaved people from the late 17th to the beginning of the 19th century) as soon as France lift its COVID restrictions, on the 19th of May. I haven’t seen the show but I listened to Marie-Yemta Moussanang‘s podcast. It’s part of the programme, in french and absolutely brilliant. The content is thought-provoking and the style compelling. And because the topics explored in the exhibition piqued my curiosity (decolonial ecology, history & fiction, women’s activism, open-source low-carbon architecture, the use of plants in political resistance, etc.), I asked the curator of the exhibition, Oulimata Gueye, if she had time for an interview. Oulimata is a Senegalese and French critic and curator who has long been investigating “the intersections between fiction, science and technology that allow for the development of critical analysis and the imagination of alternative histories.”

Rita Rainho and Angelo Lopes. Installation view at Le Lieu Unique. Photo: David Gallard

Bonjour Oulimata! I sometimes feel that the future is not something that Europeans like to think about. In the aftermath of World War 2, the future looked bright. Now there’s only climate catastrophe, the rise of sovereignty, a disenchantment with techno-scientific innovation (and maybe also with capitalism?), etc. It sometimes even feels like this pandemic will never end. I had a look at the programme of the Université des Futurs Africains. I don’t detect the kind of fatigue and sense of defeat we have in the West. Does that mean that the artists and intellectuals you invited to participate in the exhibition are less anxious about the future?

I don’t think the general tone is more optimistic than in the West and I don’t think that the invited artists are less anxious than in Europe. They place themselves in a decolonial perspective and they propose to carry out a critical examination of History, of what has been said and written in the past, of where to project oneself today from the perspective of the African continent. They have other stories to tell, to get across, other issues to explore, other ideas of potential futures to develop than the futures that were assigned to Africa in the past. In fact, most of them don’t claim to imagine the future: they open fields of research in the present that may not come to an end or a conclusion in the present. And maybe in that sense, they imagine the future.

The exhibition is the result of a critical investigation to try and understand what futures we are talking about. First of all, I try to question what we embed in the word / concept of “future”, especially when we put the African continent at the centre of the reflection.

For example, one can say that space is still perceived today as the place where “the future is invented”. As SpaceX launches its first manned space mission in 2021, how can we ensure that outer space issues are not the sole preserve of scientists and private companies? The works of Nolan Oswald Dennis and Tabita Rezaire both use the issue of space as a backdrop but they approach it from the side of those who have been forgotten or whose contribution in the history of sciences and space research we have invisibilised or dismissed. He and she demand that we consider other dimensions. Through Mamelles Ancestrales, Tabita Rezaire addresses the latest issues in space research with regard to popular knowledge, religious beliefs and spiritual questions. Accept that we coexist with elements that are beyond us. By paying homage to mythologies and to the poetic power of beliefs that link the past with the invisible, the future with the unforeseeable, the scientific with the spiritual, Mamelles Ancestrales makes a significant contribution to the question of our relationship to celestial bodies. In Black Liberation Zodiac, Nolan O. Dennis draws his energy from the culture of liberation and emancipation movements and imagines how we can reclaim knowledge that has been restricted to organizations, in a kind of back and forth motion between the collective and the individual.

Tabita Rezaire, Mamelles Ancestrales (video still), 2019

Tabita Rezaire and Nolan Oswald Dennis. Installation view at Le Lieu Unique. Photo: David Gallard

The text describing the exhibition explains that the show is inspired by the notion of “active utopia.” I’m not used to seeing these two words side by side. Again, this might be because, in the West of the 20th century, utopias ended quite badly and we grew weary of them. What is active utopia?

I borrow the term “active utopia” from Felwine Sarr. For the Senegalese economist Felwine Sarr, “All utopia is fundamentally active. It is not satisfied with dreaming of an atopos, of an elsewhere that has yet to be: it shapes it, constructs it and tries to translate its concept into actions.”

It is about considering Africa from positions and questions as concrete as to how we should take a fresh look at the place of languages, and think about the economy from a diagnosis of what works and what does not. How can we think about the means of autonomy? How can we take into account the cultural and spiritual dimensions?

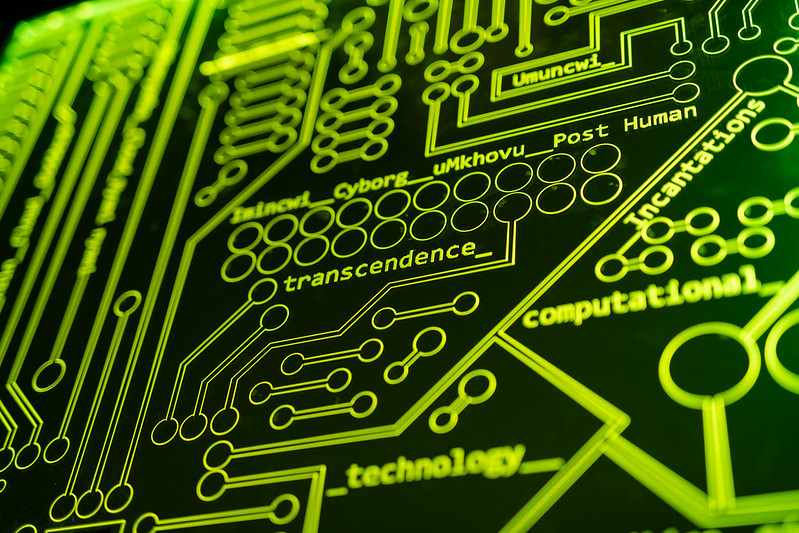

Coming back to the exhibition, the artists take charge of contemporary issues and explore alternatives articulations and this can be qualified as active utopia. In the installation A Research for Vernacular Algorithm, for example, South African artist and researcher Tegan Bristow explores how you can teach coding using bead embroidery and weaving traditions from Mozambique and from the KwaZulu province in South Africa. How can these complex objects made of pearl embroidery help us (re)think and explore digital technologies differently in order to reopen their meanings and potentials?

In the series Popular University of African Futures, Marie-Yemta Moussanang wonders if we should not replace the notion of the future with the notion of utopia.

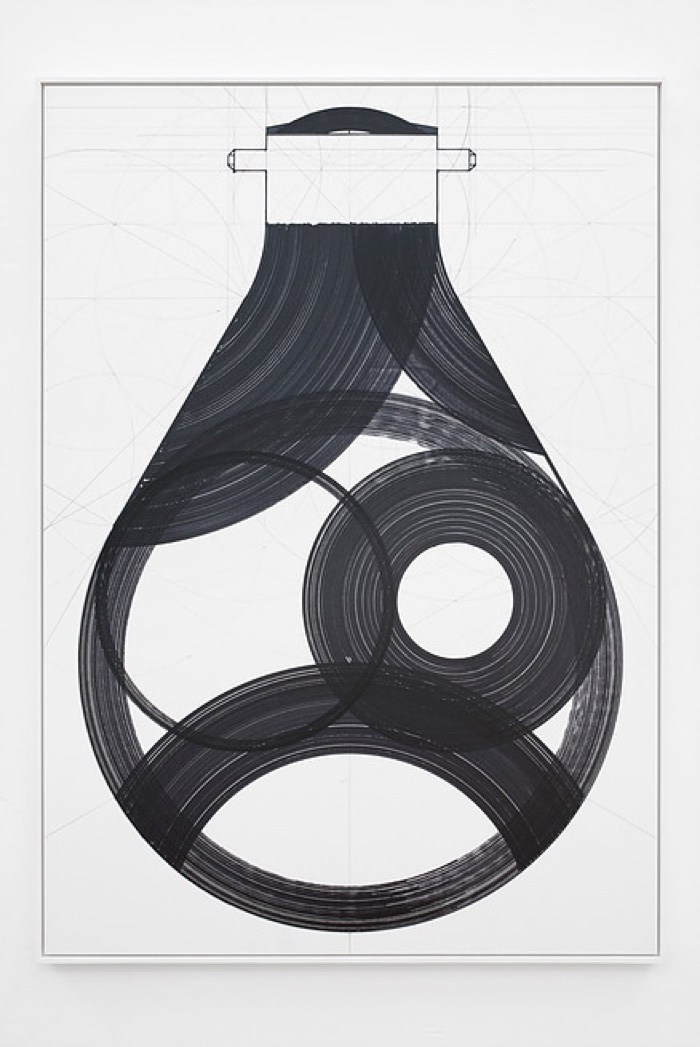

Jean Katambayi Mukendi, Afrolampes, 2016

Jean Katambayi Mukendi, Voyant, 2015. Installation view at Le Lieu Unique. Photo: David Gallard

Is there a place for the Western ways of thinking and inhabiting the world in African futures? Do they still have any use and meaning?

One of the starting points of the exhibition is the work of researcher Jenny Andersson who, in her book The Future of the World, looks back at the post World War II period and explains how different visions of the future faced each other in Europe, in USSR and in the United States. Futurology and foresight developed in part as a reaction to Third World countries that refused to align with Western visions.

The other starting point is precisely a critique of the discourse of the media and large international companies which, over the past few years, have presented Africa as the continent of the future.

In October 2015, for example, the founder of Facebook announced his plan to connect Africa from space using the AMOS-6 satellite. Visiting Nairobi and Lagos a few months later, he declared: “One of the reasons I’m here is that a large part of the future will be built here.” But what future is Mark Zuckerberg talking about? Facebook’s future?

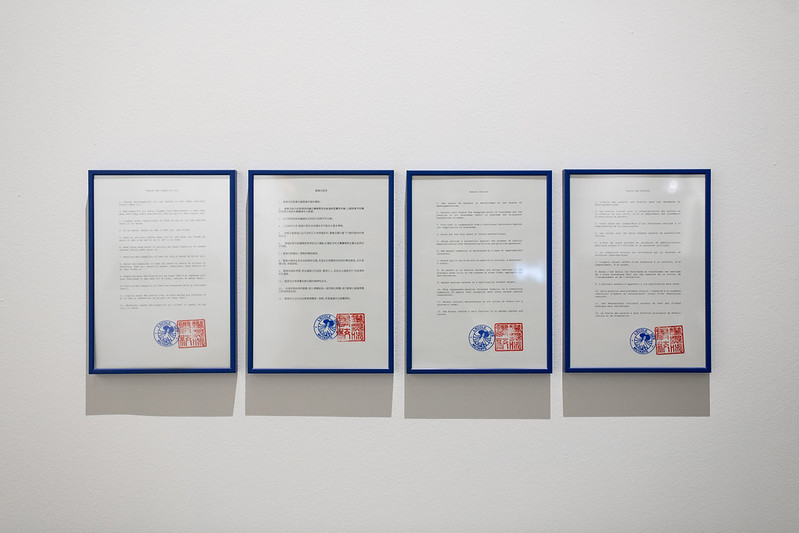

Lo-Def Film Factory (Francois Knoetze and Amy Louise Wilson), The Subterranean Imprint Archive (trailer), 2021

Lo-Def Film Factory, The Subterranean Imprint Archive, 2021. Installation view at Le Lieu Unique. Photo: David Gallard

Lo-Def Film Factory, The Subterranean Imprint Archive, 2021. Installation view at Le Lieu Unique. Photo: David Gallard

Can these artists and thinkers’ vision of the future help visitors of the exhibition reconfigure their sometimes difficult relationship to technology?

As I mentioned above, A Research for Vernacular Algorithm raises the question of algorithms and digital technologies based on the beadwork traditions of South Africa and Mozambique. Tabita Rezaire and Nolan Oswald Dennis question the place of current space events with regard to spiritual, religious and popular knowledge. In The Subterranean Imprint Archive, the collective of artists Lo-Def Film Factory explores the progress and place of Africa in digital technologies from the perspective of a historical event that changed the future of humanity: the dropping of nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Lo-Def Film Factory shows that from the 19th century onwards, the exploitation and mapping of the African subsoil become increasingly systematic and intensive, as new technologies develop. The collective also draws parallels between the futuristic side of virtual reality and a work on the importance of archives.

Hamedine Kane and Stéphane Verlet-Bottéro, The School of Mutants, 2020. Installation view at Le Lieu Unique. Photo: David Gallard

Hamedine Kane and Stéphane Verlet-Bottéro, The School of Mutants, 2020. Installation view at Le Lieu Unique. Photo: David Gallard

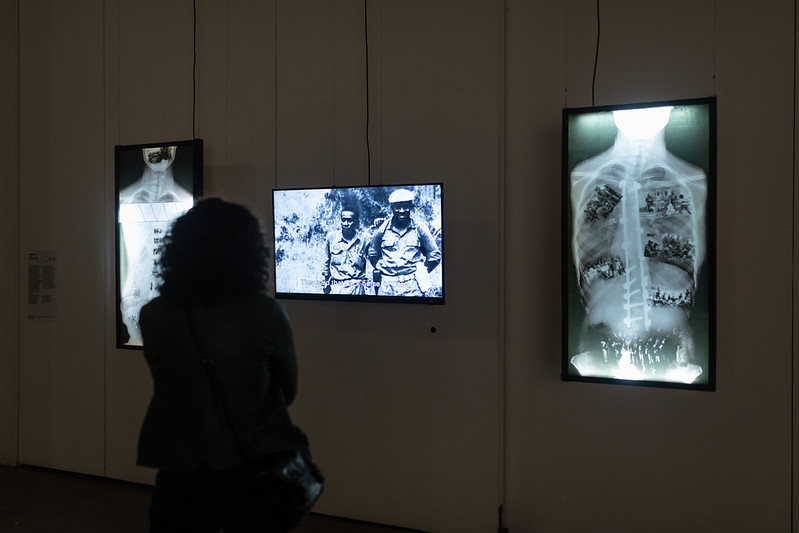

Jihan El-Tahri, Comrades, 2016. Installation view at Le Lieu Unique. Photo: David Gallard

While looking at the list of artists, I realised that I only knew the ones (some of them at least) who are based both in Africa and in Europe. Which piece of advice would you give to curators who would like to discover young artists from the African continent?

I think you have to move around, go to events organised on the continent, but also broaden your geography. I would say that for each contemporary subject a curator might be interested in, she or he must confront the question of parallel stories and how they have been obscured or transformed for the benefit of the West and how artists work on other narratives.

Thanks Oulimata!

UFA – University of African Futures is at Le Lieu Unique in Nantes, France until the 10th of August 2021. The event is organised as part of the Season Africa2020.