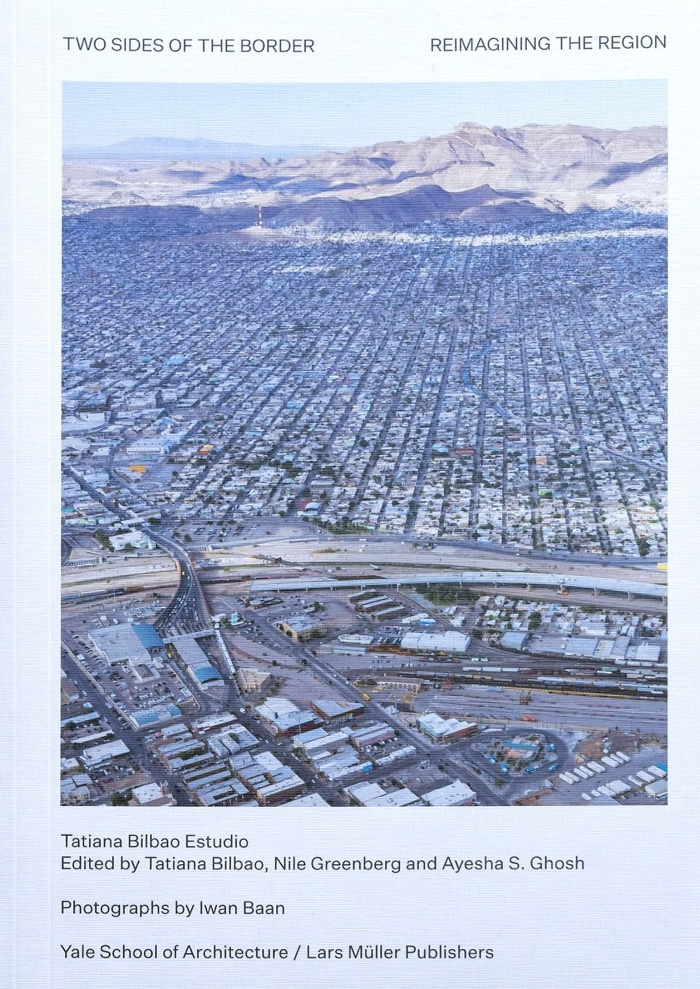

Two Sides of the Border. Reimagining the Region, edited by architect Tatiana Bilbao, designer Nile Greenberg, designer and curator Ayesha S. Ghosh, in collaboration with Yale School of Architecture.

Lars Müller Publishers writes: Under the direction of Mexican architect Tatiana Bilbao, thirteen architecture studios and students across the United States and Mexico undertook the monumental task of attempting to capture the complex and dynamic region of the US/Mexican border. Two Sides of the Border envisions the borderland through five themes: migration, housing and cities, creative industries, local production, tourism, and territorial economies. Building on a long-shared history in the region, the projects covered in this volume use design and architecture to address social, political and ecological concerns along the shared border.

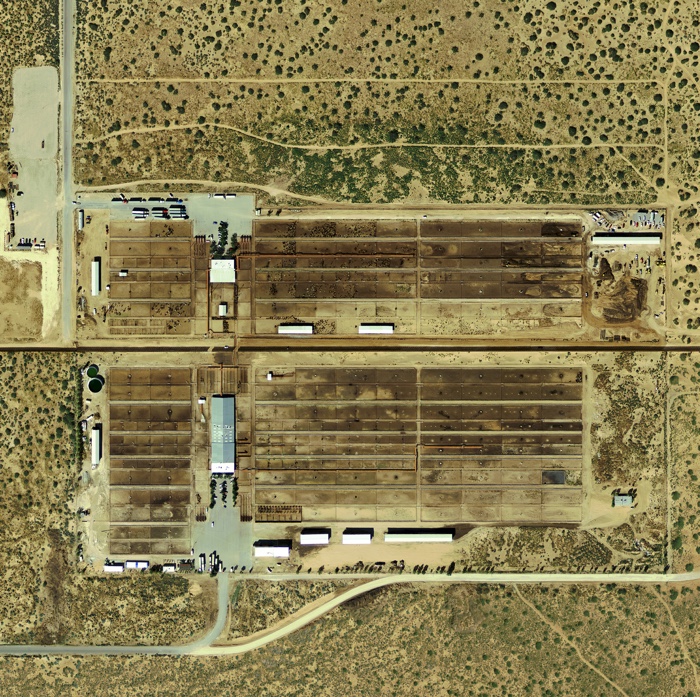

Tent city for separated children, El Paso, Texas/Ciudad Juáres, Chihuahua. Image: Iwan Baan, 2018

Two Sides of the Border is the atlas of a unique space crisscrossed and shaped by people, cultures, commerce, labour, money, natural elements, infrastructures and ideas. Officially, a line/border/wall cuts that region in two but as the book demonstrates, the reality is a bit more complex and far more interesting.

The publication combines imagination, rigorous research and a bit of activism. You need imagination to envision the reality and future of a place where the border between Mexico and the US doesn’t exist. The research comes in the form of essays by documentary makers, scholars, architects, architecture students and other thinkers who explore a territory formed by continued exchanges between two nations. But the book is also pervaded by a politically-minded spirit that disputes the current divisive rhetoric about Mexico and the United States.

The book reconciled me with the field of architecture which I’ve neglected a bit over the past few (10??) years. Here is how architect Tatiana Bilbao describes her mindset when working on the Two Sides of the Border book and exhibition deserves to be copy/pasted:

Going back to the time when architects were really thinking about the territory is what we need. I think we have lost that opportunity in the last decades of the twentieth century and the first decades of this century. Architects have moved away from thinking territorially in big movements, with a focus on planning and an understanding of society. They have done so in favor of focusing on the individual project and the potential for garnering acclaim for changing neighborhoods.

I spent a whole weekend reading the book, examining the maps and photos. Here’s a small selection of the works I found most striking:

Meatpacking plant, Union, Ohio. Image: Iwan Baan, 2018

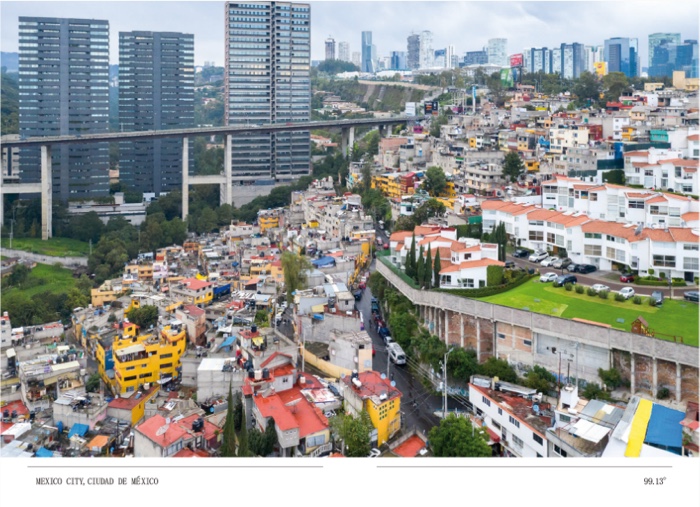

Remittance house, Puebla City, Puebla. Image: Iwan Baan, 2018

Iwan Baan‘s photos occupy about one third of the book. They speak silently about changing landscapes, hybrid architecture and cultures in constant mutations. His aerial photos, for example, show how NAFTA is far more than an economic agreement, it is an agent that physically affected the Mexican landscape and the construction industry with, for example, the development of massive industrial areas around the border.

The presentation by architecture students of projects that imagine the future of the region include Marilyn Reyes’s plan to assist monarch butterflies in their migration by providing the migrant nonhuman creatures with a space to rest in the borderlands between MX and the US; and Hallie Black’s floating building that belongs to the two states and becomes the space to push neoliberalism to its most dehumanising limits.

My favourite essay is (unsurprisingly) the one written by curator Alejandro Luperca who chose 4 artists whose works not only illustrate what it means to produce contemporary art on the border but also had a positive effect on the region and those involved.

Teresa Margolles, Irrigación [Irrigation], 2010

Luperca explains how he crossed the border together with Teresa Margolles with sheets soaked in earth, blood and other bodily secretions recovered from scenes of violence in Juárez. When stopped by the officer, they explained: “We have dirty laundry; we’re going to wash it.” The performance piece consisted of a water truck spraying the highways of Texas between Alpine and Marfa with 5000 gallons of water in which the sheets had been dipped. For the artist, this was a form of returning Texas’s waste products back to Texas — the state that exports the most firearms into Mexico.

Francis Alÿs, (in collaboration with Rafael Ortega, Julien Devaux, Alejandro Morales and Félix Blume), Paradox of Praxis 5, Ciudad Juárez, México, 2013

The shooting of Ciudad Juárez Projects with Francis Alÿs turned out to be far more risky than the video above even suggests. “Stop playing around, kids!” a municipal police officer shouted from a car in downtown Juárez, while the artist was kicking at a football ball in flames. Another patrol car stopped them, the cops pointing their weapons at Alÿs and Luperca while they were filming the stray dogs, the facades and a park where children played on swings in the distance. Their behaviour was too innocent not to look suspicious.

Enrique Jezik, Volveré y Seré Millones (I Will Return and I Will Be Millions), 2017

Enrique Jezik’s Volveré y Seré Millones (I Will Return and I Will Be Millions) project involved the installation of a banner on the Mexican side of the border. The slogan was also visible to the border patrol officers posted on the other side of the bridge. The phrase was first attributed to Túpac Amaru II, the Peruvian indigenous leader of a rebellion against the Spaniards in 1781 who was subsequently brutally executed and dismembered. Before the executioner cut out his tongue, Amaru is said to have pronounced the phrase in both Spanish and Quechua: “Tikrashami hunu makanakuypi kasha.” Ježik connects this emblematic, historical slogan of resistance to the forced repatriation of undocumented migrants.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Border Tuner / Sintonizador Fronterizo, Relational Architecture 23″, 2019. Photo by Monica Lozano

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, Border Tuner / Sintonizador Fronterizo, Relational Architecture 23″, 2019. Photo by: Mariana Yañez

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s Border Tuner interconnected El Paso and Ciudad Juárez using powerful robotic searchlights and live sound channels for communication across the border. Bridging both sides of the border, the installation emphasises the continuous collaboration that links the two cities and the two countries and provides a counter-narrative to the toxic rhetoric on the border.

Ersela Kripa wrote about her Nephelometry project: a network of low-cost dust sensors along the US–Mexico border. Low-cost sensor bundles installed on both sides of the frontier collect information on air pollution and its movement from one area to another. The mappings of the measurements defy the border wall, highlighting the shared airshed and ecological damage in the border region due to infrastructural and environmental neglect.

Stephen Mueller has a fascinating essay on borderland space and atmosphere. While dusty air and desert conditions are detrimental to the wellbeing of people who inhabit the area or walk through it, they can be exploited by military and security experts. In their eyes, the diverse desert atmospheres of the area constitute ready-made environmental adversaries. Training sites are thus strategically set up in the borderland.

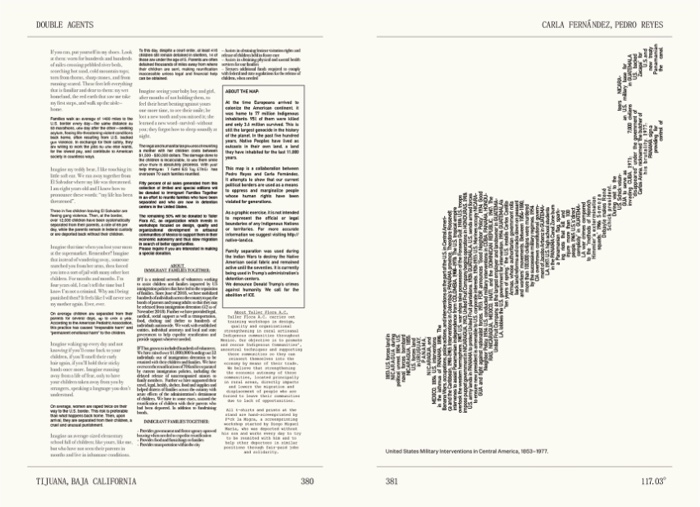

Two Sides of the Border. Reimagining the Region. Book spread

Carla Fernàndez and Pedro Reyes‘s contribution reflects the US countless military interventions and overthrowing of regimes in Central America over the last two centuries. Its violent and destructive (overt or covert) foreign policy often violates international human rights laws and has forced thousands of Central Americans to seek asylum elsewhere. The two maps they created draw attention to the moral and legal responsibility of care owed to these refugees by the United States.

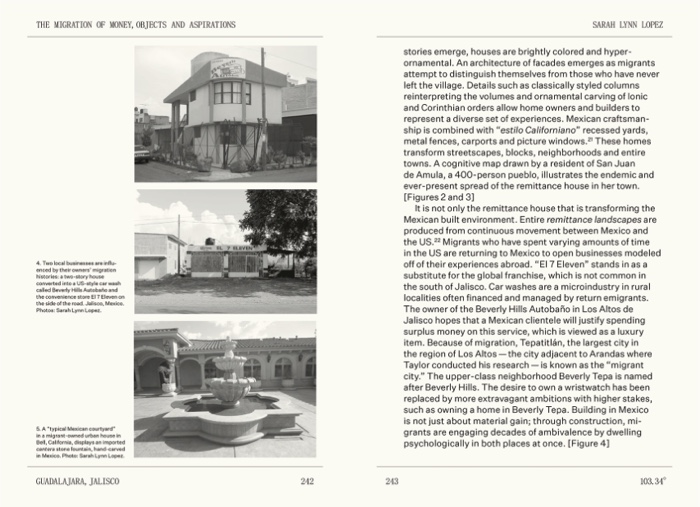

Sarah Lynn Lopez investigated the crisscrossing of objects, dollars and aspirations carried by individuals who lead transborder lives between Mexico and the US. One of the many examples she gives is cars and the impact they had on Mexican landscapes, spaces and infrastructures. In the early 20th century, approximately one out of every three migrants brought a car back with him or her to Mexico. This influx of automobiles led to the construction of roads. Her essay made me want to buy her book The Remittance Landscape.

More photos from the book:

A view across the border from El Paso towards Ciudad Juarez. Image: Iwan Baan, 2018

US-Mexico Eastern beach border. Image Credit: Thomas Paturet

San Ysidro Port of Entry. Image Credit: Thomas Paturet

Union Ganadera Ciudad Juarez. Image Credit: Thomas Paturet

Two Sides of the Border. Reimagining the Region. Book spread

Two Sides of the Border. Reimagining the Region. Book spread

Two Sides of the Border. Reimagining the Region. Book spread

Previously: Transnationalisms – Bodies, Borders, and Technology. Part 1. The exhibition; Book review – Über Grenzen. On Borders; Unstable Territory. Borders and identity in contemporary art; VOTEMOS.US – Mexico decides; Hyper-Border: The Contemporary U.S.-Mexico Border and its Future, etc.