This year, Turbulence is celebrating its 10-year anniversary. Over the decade, the New York-based organization has commissioned over 110 pieces ($450,000) and exhibited and promoted artists’ work through its Artists Studios, Guest Curator, and Spotlight sections. As networking technologies have developed wireless capabilities and become mobile, Turbulence has done a fantastic job by commissioning, exhibiting, and archiving the new hybrid networked art forms that have emerged.

This year, Turbulence is celebrating its 10-year anniversary. Over the decade, the New York-based organization has commissioned over 110 pieces ($450,000) and exhibited and promoted artists’ work through its Artists Studios, Guest Curator, and Spotlight sections. As networking technologies have developed wireless capabilities and become mobile, Turbulence has done a fantastic job by commissioning, exhibiting, and archiving the new hybrid networked art forms that have emerged.

I came to discover Turbulence through their blog networked_performance run mostly by Jo-Anne Green (her bio). As everyone who’s involved at some point in new media art follows the blog religiously, i asked her to tell me more about the Turbulence organization, how it works, commissions, and, well… how it is financed.

Turbulence is 10 years old. How did it start? With what objectives?

Helen Thorington, founder of Turbulence, came to the net via radio. She was the founder and executive producer of New American Radio (NAR), a series of over 300 experimental sound and radio art works commissioned over an 11-year period (1987-1998). Although some of its programs where aired in Europe and Australia, NAR was primarily dependent on the American public radio system for distribution. Within months of receiving a major grant from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), the series was subjected to a focus group, where its unfamiliarity proved detrimental. Labeled “minorityâ€? programming and criticized in advance for its inability to draw a large audience, it was aired by only a small number of public radio stations. While it remained on air for over ten years, and was loved and respected by stations committed to arts programming, the pressure placed on public stations to increase their audiences eventually lead to a decrease in air time for all arts programming and the suppression of the programming it was intended to support–“programs of high quality, diversity, creativity, excellence and innovation,â€? not feasible in a commercial system.

Helen Thorington, founder of Turbulence, came to the net via radio. She was the founder and executive producer of New American Radio (NAR), a series of over 300 experimental sound and radio art works commissioned over an 11-year period (1987-1998). Although some of its programs where aired in Europe and Australia, NAR was primarily dependent on the American public radio system for distribution. Within months of receiving a major grant from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), the series was subjected to a focus group, where its unfamiliarity proved detrimental. Labeled “minorityâ€? programming and criticized in advance for its inability to draw a large audience, it was aired by only a small number of public radio stations. While it remained on air for over ten years, and was loved and respected by stations committed to arts programming, the pressure placed on public stations to increase their audiences eventually lead to a decrease in air time for all arts programming and the suppression of the programming it was intended to support–“programs of high quality, diversity, creativity, excellence and innovation,â€? not feasible in a commercial system.

The Internet promised a free, open, and participatory distribution mechanism. In 1996 Helen began making NAR available to audiences world-wide via http://somewhere.org. During the process, she and her colleague Harris Skibell began exploring the creative possibilities of the net and Turbulence was born. The continuity of Helen’s sound/radio interests is evident in many of the early works and continues to this day.

Do you feel that the public is more open to the kind of art work Turbulence is supporting than it was 10 years ago? How about the art market? How do you see the situation evolving over time?

It’s difficult to grasp who exactly Turbulence’s “public� is. Our public is dispersed across the globe and ranges from geeks to activists, music aficionados, literary enthusiasts, mathematicians, and painters. Some come to Turbulence via slashdot and digg, others from the Whitney Museum of American Art or other net art portals like Netbehaviour, New Media Fix, Neural, Noema and Rhizome. They are in Brazil, Iceland, Korea and South Africa. While mainstream art world demographics can be similarly diverse, museum and gallery audiences tend to (have to) have some knowledge of art. This has presented a problem for many “ivory tower� institutions—the Guggenheim in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. It’s evident in the motorcycle and fashion shows they produced to bring non-art audiences into their buildings (for which they have been heavily criticized by the art world). Ironically, these types of shows raise the question “is it art?�, a question very familiar to net artists.

There’s a very broad spectrum of art on the net, ranging from easily accessible works to others in the “insider,� “art for art’s sake� vein, and still others that are very technically challenging. While net art is still marginalized as far as the art world is concerned, it’s actually quite accepted by internet savvy audiences. Art history and appreciation are not a pre-requisite for meaningful experiences. In fact, many net artists themselves do not have arts backgrounds. Rather, their skills are grounded in computer hardware and code and they’re often unaware of the contiguous, art historical precedents their work references. This is not necessarily disadvantageous. There’s something to be said for traveling light.

I see “the public� and “the art market� as different entities that occasionally converge. When you consider the mainstream art market and the relatively narrow public it serves, juxtaposed with the promise of the Internet—bottom-up, participatory, low cost distribution mechanism—net art is accessible to a far wider audience. Yet, many feel that without the legitimacy afforded by traditional art world establishments—museums, galleries, collections—net art cannot survive. As things stand, I don’t see how these two worlds can ever merge. The art world still wants art stars and still needs physical objects that can be bought and sold. Who would want to invest in an art work that cannot be preserved, or that has no original and possibly infinite copies? A lot of networked art is about experiences not things. It is unpredictable, in flux, open to input, and dependent on its users. It will always need its own funding mechanism—grants, residencies, live events. Why even attempt to fit a square peg into a round hole?

I’m sometimes told that art organizations have it easy in Europe. I don’t know how much it’s true. How do you finance your activities, commissions and the people who work for Turbulence?

We also have that sense, though it’s a particularly bad time in the United States. Beginning with Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, the rising neo-conservative wave that has carried the US into its current era of pre-emptive war and imposed “democracy� has hampered creativity and innovation at home. Like the CPB, the National Endowment for the Arts has been held hostage by conservative ideology and fear of the unpredictable. Conservatives are also responsible for greatly diminished regional social and education programs and that, coupled with cost of waging war, has resulted in drastic reductions in support for people in positions like ours. We’re a tiny organization. It’s just Helen and I, and our very part-time system administrator, Jesse Gilbert. So, we’re struggling and have been for several years. We don’t know whether we’ll be around from one year to the next. That’s not to say we do not get support from the NEA and many other foundations. It’s just that when the NEA stopped funding individual artists in the early 90’s, it fell upon organizations like ours to fill that void. We spend a lot of time writing grant proposals but, when they succeed, most of the money goes towards our programs. This is, indeed, part of our mission: to support emerging and established artists. But, there’s an expectation that we can do this without putting bread on our own table and having basic tools like computers and software.

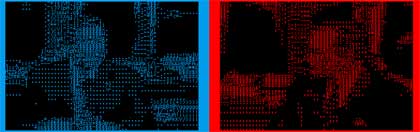

html_butoh

html_butoh

Can you tell us a few words about the latest works you commissioned? Which criteria guided the selection?

Turbulence’s strength is the diversity of its commissioned works. Helen’s background is in literature and sound. Mine is in the visual arts (I was a printmaker, then a painter and book artist). We both have a deep connection to dance; Helen has composed for it and I grew up watching it. And we care deeply about human rights and political activism. This definitely influences our choices, but there are other criteria we look for as well. How effectively does the work make use of networked and database technologies? How open is it to user participation? What type of experience will the user have? That said, we are not solely responsible for choosing the works we commission; we often have juried competitions. For instance, the juried international competition currently underway –Mixed Realities— has five jurors. This is the second competition we’ve run where the commissioned works are exhibited in both physical and virtual space. Rather than looking for work for the Internet we’re asking practitioners to consider how a piece might function in various spaces, and to make the piece with those parameters in mind. Mixed Realities calls for projects that can be exhibited in three discrete spaces: Turbulence (an Internet gallery), Ars Virtua (a Second Life gallery), and Art Interactive (a physical gallery).

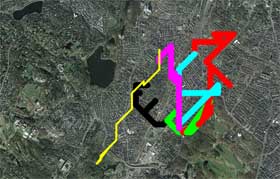

Recent examples of commissioned work include Cell Tagging by Brooke A. Knight which employs the cell phone as a digital graffiti tool for marking and remembering personal space (image on the right); html_butoh by Ursula Endlicher, an open database of user-performed HTML code; and Gothamberg by Martin Wattenberg and Marek Walczak which weaves a web of connections—passageways, hallways, stairways–between contributors through their personal stories about living in an apartment.

Recent examples of commissioned work include Cell Tagging by Brooke A. Knight which employs the cell phone as a digital graffiti tool for marking and remembering personal space (image on the right); html_butoh by Ursula Endlicher, an open database of user-performed HTML code; and Gothamberg by Martin Wattenberg and Marek Walczak which weaves a web of connections—passageways, hallways, stairways–between contributors through their personal stories about living in an apartment.

Let’s talk about one of Turbulence most visible projects: the networked_performance blog. It started with the aim to uncover commonalities in network-enabled works. That was nearly 3 years ago. Did see some commonalities emerge? If yes, which ones?

I think the strongest connection between much of the work is how much the roles of “artist� and “audience� have shifted. Because so many networked pieces rely on the people formerly known as the audience to “complete� them, there’s a level of performativity—or user action—required, whether users are playing mixed reality games, or adding their stories to a database of hundreds of others’ stories. There’s a level of physical engagement—from the miniscule click of a mouse, to drawing and typing, to the choreography of full-bodied movement—that has turned the paradigm of solitary digital immersion and disconnection on its head. In fact, networked art experiences can be far more connected and “real� than traditional art ‘experiences’. Sure, paintings elicit visceral and deeply emotional responses, and to some extent allow the viewer to complete them. But those experiences are often intensely private and self-contained. Watching participants draw together in public or jump up and down to effect an installation, you cannot help but be aware of how categorically social networked art can be and just how strong the desire to connect with other people is. People want to feel like they’re making a difference and that there’s a role for them to play. Digital networks are making this possible.

Gothamberg

Gothamberg

Are there art projects from the past that keep having an influence on today’s art projects? How do you explain their lasting influence?

One can definitely trace much of today’s practice to Marcel Duchamp/Dada, John Cage, Alan Kaprow/Happenings, Fluxus, and the Situationists (and many more). The shift from passive audience to engaged participant, non-linearity, chance and randomness and the question “what is art?� all derive from these artists and movements. Ironically, these user-centric precedents—you, afterall, can be an “artist� too—have historically alienated traditional art audiences. For centuries, the western artist was elevated above society (Martha Woodmansee’s 1994 study, The Author, Art, and the Market: Rereading the History of Aesthetics, provides a detailed analysis of how changing market conditions in the eighteenth century facilitated the development of a romantic view of authorship), perceived as the solitary genius whose objects are eventually valued beyond almost anything else in western culture (from an investment standpoint). After many years, the sudden shift to urinal–as-art was an enormous affront to the public. Even though the every day is far more accessible and inclusive than the rare, extraordinary gifts of the few, the public quickly became more comfortable with “experts� telling them what is and is not art. There are strong human tendencies toward the dissolution of the boundary between art and life, but art institutions are clinging to their privileged place in our culture. Networked technologies are revolutionizing society. It’s impossible to predict where they will take us, but clearly, our way of life is going to radically change. Hopefully, the art world will change too.

One can definitely trace much of today’s practice to Marcel Duchamp/Dada, John Cage, Alan Kaprow/Happenings, Fluxus, and the Situationists (and many more). The shift from passive audience to engaged participant, non-linearity, chance and randomness and the question “what is art?� all derive from these artists and movements. Ironically, these user-centric precedents—you, afterall, can be an “artist� too—have historically alienated traditional art audiences. For centuries, the western artist was elevated above society (Martha Woodmansee’s 1994 study, The Author, Art, and the Market: Rereading the History of Aesthetics, provides a detailed analysis of how changing market conditions in the eighteenth century facilitated the development of a romantic view of authorship), perceived as the solitary genius whose objects are eventually valued beyond almost anything else in western culture (from an investment standpoint). After many years, the sudden shift to urinal–as-art was an enormous affront to the public. Even though the every day is far more accessible and inclusive than the rare, extraordinary gifts of the few, the public quickly became more comfortable with “experts� telling them what is and is not art. There are strong human tendencies toward the dissolution of the boundary between art and life, but art institutions are clinging to their privileged place in our culture. Networked technologies are revolutionizing society. It’s impossible to predict where they will take us, but clearly, our way of life is going to radically change. Hopefully, the art world will change too.

What’s the biggest challenge that the Turbulence organization has to face these days?

Making a living so we can keep on keeping on.

Do you think that the future of network-enabled art is bright? Will it merge one day with the “traditional art” world?

The future is very bright as long as the Internet does not wind up in the hands of corporations and/or micromanaged by governments. Net art’s greatest asset is that almost anyone (with access to a computer and the Internet) can create experiences and share them with the public. Turbulence may not last, but there will always be other Internet portals.

Thanks Jo-Anne!

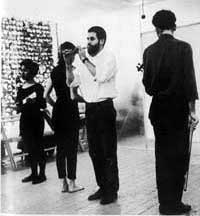

Last image of the interview is Allan Kaprow, “18 Happenings in 6 Parts”, 1959.