Peter Cusack, Bibi Heybat Oilfield, Baku, Azerbaijan

Peter Cusack, Bibi Heybat Oilfield, Baku, Azerbaijan

Ferris wheel in Chernobyl exclusion zone. Photo Peter Cusack

Ferris wheel in Chernobyl exclusion zone. Photo Peter Cusack

Peter Cusack is a field recordist, musician and researcher who has traveled to areas of major environmental devastation, nuclear sites, big landfill dumps, edges of military zones and other potentially dangerous places. He has been to the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone; the Caspian Oil Fields in Azerbaijan; ‘London Gateway’ the new port on the River Thames where massive dredging severely damages the underwater environment; the Aral Sea, Kazakhstan, which is now being partially restored after virtually disappearing due to catastrophic water misuse.

While most of these locations have been extensively discussed in articles and documented in images, we don’t know what a day in any of these places sounds like. With his field recordings, however, Cusack gives us an idea of what a radiometer with a cuckoo in the background in Pripyat sounds like. Or what it is like to hear the wind whistling by the Sizewell nuclear power stations. These recording belong to a practice that the artist calls sonic journalism. The discipline is an audio complement and companion to images and language. Using field recordings and careful listening, sonic journalism provides valuable insights into the atmosphere of a particular site.

You can listen to some of the field recordings online (Sounds from Chernobyl + Caspian Oil and UK Sites.) Some are very moving. All made me want to contact Peter Cusack and ask him a few questions:

Hi Peter! The public is now used to seeing images of dangerous places. Focusing on sound recordings from these same places, however, is less banal. What can sound communicate that an image cannot convey?

Hi Peter! The public is now used to seeing images of dangerous places. Focusing on sound recordings from these same places, however, is less banal. What can sound communicate that an image cannot convey?

Field recordings are very good at communicating the atmosphere of places. They also give a good sense of space (distance, position, how things are moving) and timing of any events happening. I think this is important because it gives a sense of what it might be like to actually be there and allows you to think about what you might feel, or how you might react if present. I don’t really agree that images are more banal (some recordings are also). It depends on the image. For me a better impression is given when images, sounds and language are working together. Most reportage uses images and language but not the sounds, which means we are usually missing the aural information. This is a pity because it can be very informative and expressive.

Peter Cusack, Ship’s Graveyard, Aral Sea, Kazakhstan

Peter Cusack, Ship’s Graveyard, Aral Sea, Kazakhstan

Bibi Heybat oilfield. Photo Peter Cusack

Bibi Heybat oilfield. Photo Peter Cusack

Some of the sounds you collected are seducing and fascinating. The ones you recorded in the Chernobyl exclusion zone are particularly charming, even the Cuckoo and radiometer has some poetry in it. So how do you suggest the sense of danger to the listener?

Yes, sometimes they are a complete contrast to a sense of danger. However they are part of the the larger whole. Most dangerous places are very complex. For me it’s important to suggest the complexity and the contradictions that are present. That way one gets a more complete picture, e.g it may seem a contradiction that the Chernobyl exclusion zone is now a wonderful nature reserve. That is definitely to be contrasted with state of human health there.

Shoes in the Chernobyl exclusion zone. Photo Peter Cusack

Shoes in the Chernobyl exclusion zone. Photo Peter Cusack

Photo Peter Cusack

Photo Peter Cusack

Photo Peter Cusack

Photo Peter Cusack

Photo Peter Cusack

Photo Peter Cusack

View of Pripyat. Photo Peter Cusack

View of Pripyat. Photo Peter Cusack

Is it easier to get access to these locations as a sound artist than as a photographer? I imagine that people in charge of a military site or a particularly environment-damaging oil field will be wary of a photographer but might underestimate the strength of a sound recording. Do you find that you face the same resistance and restriction when you record ambient sound than when you take photos?

The only place where i had access to a place where photographers cannot not go was the Jaguar car factory in Liverpool, where they are paranoid about industrial espionage from rival car manufacturers. At Chernobyl they give anyone access if you can pay the entry fees.

In places where you don’t get permission it depends on how obvious you are. Large microphones are as visible as large cameras. I often use small equipment which is not easy to see. However, it’s true that security guards don’t know about recording equipment compared to cameras.

The UK now is very security conscious. I’ve been stopped at places for recording and for just standing in the wrong place not recording or photographing.

These days it helps to know the law regarding recording of any kind.

Bradwell, UK. Photo Peter Cusack

Bradwell, UK. Photo Peter Cusack

Lakenheath runway. Photo Peter Cusack

Lakenheath runway. Photo Peter Cusack

The first recordings of the series dedicated to the oil industry were made in 2004 at the Bibi Heybat oil field, in Azerbaijan. Why did you start there? Was it a conscious decision to start in that location or did you find yourself there for another reason and the idea emerged then to start a new body of work?

i was in Azerbaijan for a holiday. i did not know the oil fields were there, so it was a very lucky accident from which the project grew.

You see Sounds from Dangerous Places as a form of ‘Sonic Journalism’. Yet, you are a sound artist, so what makes your work an artwork rather than merely a ‘sound reportage’?

My interest is to document places as best i can (audio recording, photography plus any other kind of material or research) so that anyone listening/reading can get an idea of the place itself and the relevant issues. this material gets used for a variety of purposes – sound art, cds, radio, education, talks, installations. whether it is art, documentary or journalism is not so important to me.

Oil field. Photo Peter Cusack

Oil field. Photo Peter Cusack

Are there dangerous places you wish you could go to or sounds you wish you could capture, only they are out of reach for some reason?

Yes, many. most military areas are completely impossible to get into. So are a lots of industrial sites, nuclear power stations, etc. Sometimes official tours are organised but usually these are useless for recording, which takes time to do properly without other people talking or getting in the way all the time. However it’s sometimes possible to make interesting and valuable recordings from outside the fences.

Other places are really, and personally, dangerous like war zones. My project concentrates on environmentally dangerous place. War zones are not part of this and i’ve no wish to get killed.

After this exploration of the energy industry, you are planning to explore global water issues. Can you tell us a bit more about this project? Your website states that the work will include the dam projects in Turkey. Why do these dams strike you as representative of the global water problems? Where else will the project take you?

The Aral Sea in Kazakhstan. the aral sea was once the 4th largest lake in the world. today it has almost dried up because the water flowing into it is diverted into major irrigation schemes far up stream. The disappearance of the sea has been disastrous for the local climate and huge fishing industry that once supplied the Soviet Union with 25% of its fresh water fish.

The Kazakhs are now trying to restore a small part of the sea with support from the world bank. This has been quite successful and the fishing industry has re-started bring the economy back to some of the fishing villages. the wildlife has returned and so has the climate. I have travelled there twice so far – very interesting.

Thanks Peter!

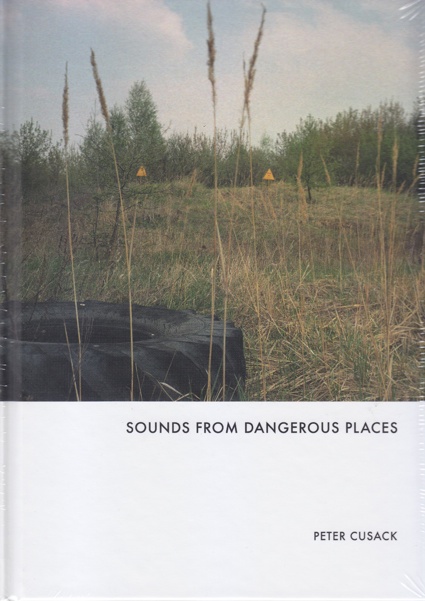

Check out the CDs and accompanying book that bring together extensive field recordings, photos and writing from the work in Chernobyl, Caspian oil, and UK sites.

Check out the CDs and accompanying book that bring together extensive field recordings, photos and writing from the work in Chernobyl, Caspian oil, and UK sites.

Sounds From Dangerous Places is part of HLYSNAN: The Notion and Politics of Listening at the Casino de Luxembourg until 7.9.2014.