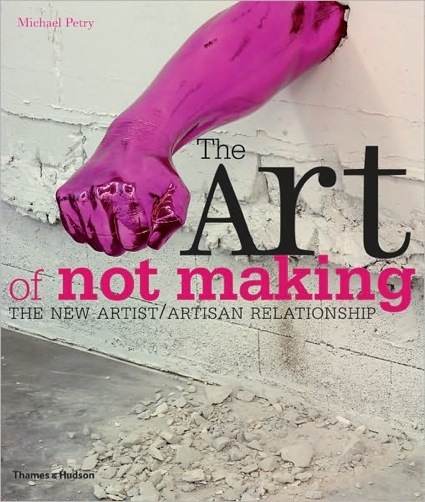

The Art of Not Making: The New Artist / Artisan Relationship, by Michael Petry.

Available on Amazon USA and UK.

Publisher Thames & Hudson writes: Can an artist claim that an object is a work of art if it has been made for him or her by someone else? If so, who is the ‘author’ of such a work? And just what is the difference between a work of art and a work of craft?

The Art of Not Making tackles these questions head on, exploring the concepts of authorship, artistic originality, skill, craftsmanship and the creative act, and highlighting the vital role that skills from craft and industrial production play in the creation of some of today’s most innovative and sought-after works of art.

Michael Petry presents the art of over 115 contemporary artists – including Takashi Murakami, Matthew Barney, Tony Cragg, Cornelia Parker, Grayson Perry, Ai Weiwei, Daniel Buren and Carsten Höller – all of whom have one thing in common: they do not always make their own work. Instead, they often either employ others to produce it on their behalf, or appropriate objects made by someone else. Original interviews with the artists and artisans offer insights into this creative collaboration, which often produces works breathtaking in their scope and ambition.

Carsten Höller, Rhinoceros, 2005

Carsten Höller, Rhinoceros, 2005

Painters of the Renaissance did it, Damien Hirst does it and so does Takashi Murakami. Marcel Duchamp became one of the most influential artists in history for doing it. Each of these artists rely on external assistance to ‘do their job.’ Some have an idea for an artwork and entrust an assistant or the expert of another discipline or craft to actually make the whole piece. Others delegate only part of the process. We know that. Yet, in the mind of the public, the artist is still this individual of great mind, impeccable dexterity and expertise who’s behind every single element of his work.

Interestingly, Michael Petry draws parallels with cinema. A film is the result of a collaborative effort between actors, technicians, assistants, writers, etc. Yet, we never question the fact that it is the film director who is credited as the maker of the film.

Petry believes that the rise in this partnership between the artist and the artisan is partly due to the return in favour of a highly crafted aesthetic in art, an aesthetic that contrasts with the mass-manufactured one. Another factor is that museums and galleries need to create ‘spectacles’ that will attract visitors, and that often entails works of spectacular proportions, a challenge that usually requires the involvement of more than one person/skill.

The author had the pragmatic idea of interviewing (or maybe he had an assistant do it for him?) artists as well as professional makers and artists who work for other artists. He asks them the reason for their collaboration, how they deal with production issues, authorship issues and what happens when one of the parties is not satisfied with the final object.

The book is quite light in theory (since The Art of Not Making is one of those coffee table trophies, theories was probably not the whole point anyway) but it still manages to provide a historical perspective, a few thought-provoking ideas, many questions and almost as many leads to help readers answer them for themselves. It also contains hundreds of illustrations and for each artwork, the author attempts to retrace the production and the technical skills necessary to complete the piece.

Quick selection:

A mushroom cloud weighting several tons and made of brass cooking utensils.

Subodh Gupta, Line of Control, 2008

Subodh Gupta, Line of Control, 2008

Wool tapestry based on an engraving showing rioters burning and looting an orphanage in New York, partly hidden by the hand-cut felt silhouette of the hanged woman.

Kara Walker, A Warm Summer Evening in 1863, 2003

Kara Walker, A Warm Summer Evening in 1863, 2003

Rug produced by hand by women rugmakers in Arraiolos, Portugal, using a traditional needlepoint stitching technique invented there.

Carlos Noronha Feio, The End (Birth and Fertility – The Good News), 2008

Carlos Noronha Feio, The End (Birth and Fertility – The Good News), 2008

The artist collected dead fighting dogs and lapdogs and had them stuffed and preserved by professional taxidermists.

Jochem Hendricks, Siblings, 2008

Jochem Hendricks, Siblings, 2008

Jochem Hendricks, Siblings, 2008

Jochem Hendricks, Siblings, 2008

I’ll never get tired of this one! Working with a taxidermist, the artist had the life-size cast made from a living animal. Body is made of polyvinyl, polyurethane foam and polyester resin. Eyes and horns are made of glass.

Carsten Höller, Hippopotamus, 2007

Carsten Höller, Hippopotamus, 2007

Animal Group, 2011. Installation view, “Experience,” New Museum. Photo © Benoit Pailley

Animal Group, 2011. Installation view, “Experience,” New Museum. Photo © Benoit Pailley

Shedboatshed (Mobile Architecture No 2) is a real wooden shed that the artist bought, dismantled, reassembled into a boat which he rowed down the Rhine, dismantled then reassembled again as a shed to be exhibited in a Basel museum.

Simon Starling, Shedboard (Mobile Architecture N0 2), 2005

Simon Starling, Shedboard (Mobile Architecture N0 2), 2005

Houshiary and architect Pip Horne oversaw the fabrication of handmade clear-glass panels which were etched with patterns based on her paintings. The new window replaces the one that had been damaged by WWII bombings.

![]() Shirazeh Houshiary, Commission for St Martin-In-The-Fields, 2008

Shirazeh Houshiary, Commission for St Martin-In-The-Fields, 2008

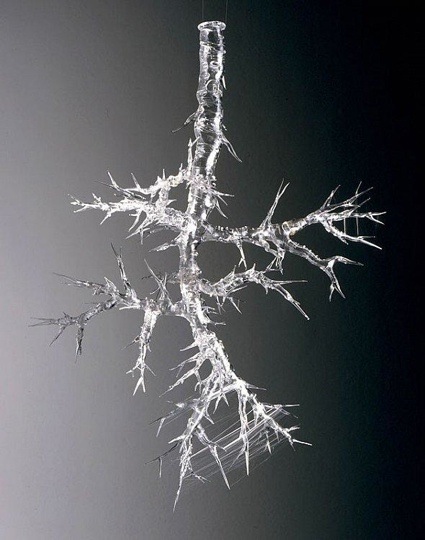

Branching bronchia of a human lung made from glass and partially wrapped in silk extracted from the golden orb weaver spider. The silk is being developed for use in bullet-proof vests.

Christine Borland, Bullet Proof Breath, 2001

Christine Borland, Bullet Proof Breath, 2001

Doves made from Murano glass, then covered in ink.

Jan Fabre, Shitting Doves of Peace and Flying Rats, 2008

Jan Fabre, Shitting Doves of Peace and Flying Rats, 2008