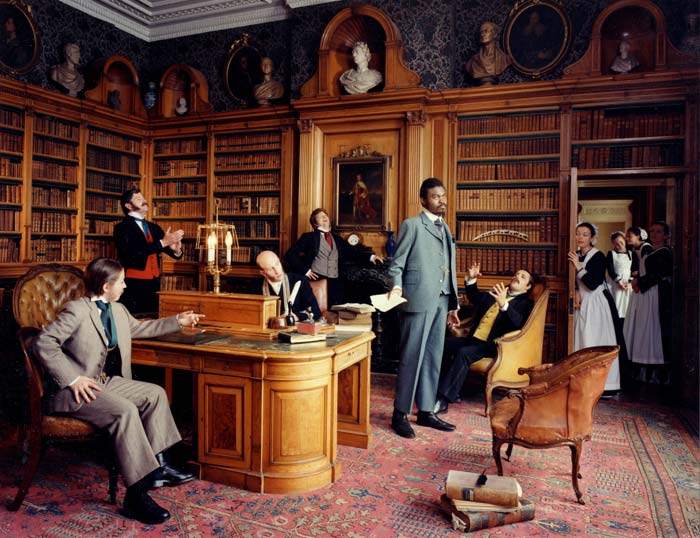

The Photograph as Contemporary Art (new edition), by author and curator Charlotte Cotton.

Publisher Thames & Hudson write: A new edition of the definitive title for students and teachers in the field of contemporary art photography. Updated throughout to reflect contemporary perspectives on the most significant moments in photography’s recent history, with the final two chapters extensively revised to reflect on new technologies, approaches and dialogue with established traditions in photography-as-art.

Publisher Thames & Hudson write: A new edition of the definitive title for students and teachers in the field of contemporary art photography. Updated throughout to reflect contemporary perspectives on the most significant moments in photography’s recent history, with the final two chapters extensively revised to reflect on new technologies, approaches and dialogue with established traditions in photography-as-art.

Photography is by far my favourite art form. It can be easy and immediate. And it can hide multiple layers of meaning and references. Photography also gives visibility to people, practices and places that mainstream visual media fails to notice.

I’ve reviewed a dozen or more books about photography on this blog. What makes The Photograph as Contemporary Art stand out from crowded library bookshelves is its compact format that allowed me to take it on train trips across Belgium last month. Despite its smallish size, the volume manages to explore the work of over 350 photographers, many of them new to me.

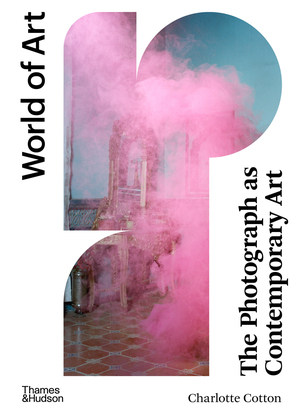

Tatsumi Orimoto, Bread Man Son and Alzheimer Mama, Tokyo, 1996

Mona Hatoum, Van Gogh’s Back, 1995

But the reason why I want to recommend this book is that it is a fun one. It targets an audience of art viewers but there’s none of the (stale) arty mumbo jumbo. There’s humour throughout the pages and there’s inventiveness in the categories Cotton chose to classify contemporary photography art. You’d expect these categories to be portraits, landscapes, documentary, abstraction or still life but the author is too farsighted and experienced to comply with readers expectations. Here are photo works and categories I discovered in this little gem of a book:

The first category, If This Is Art, considers how photographers orchestrate performances, scenarios and happenings for the camera. The image is the end goal, the testimony of an action never to be repeated.

Nona Faustine, From Her Body Sprang Their Greatest Wealth, 2013

In her White Shoes series, Nona Faustine visualizes the legacy of oppression, dehumanisation and violence against people of colour. In the image above, she stands on a wooden box in the middle of Manhattan’s Wall Street, a clear reference to the site of an eighteenth-century slave market and to a financial wealth that would not have been possible without the exploitation of enslaved people.

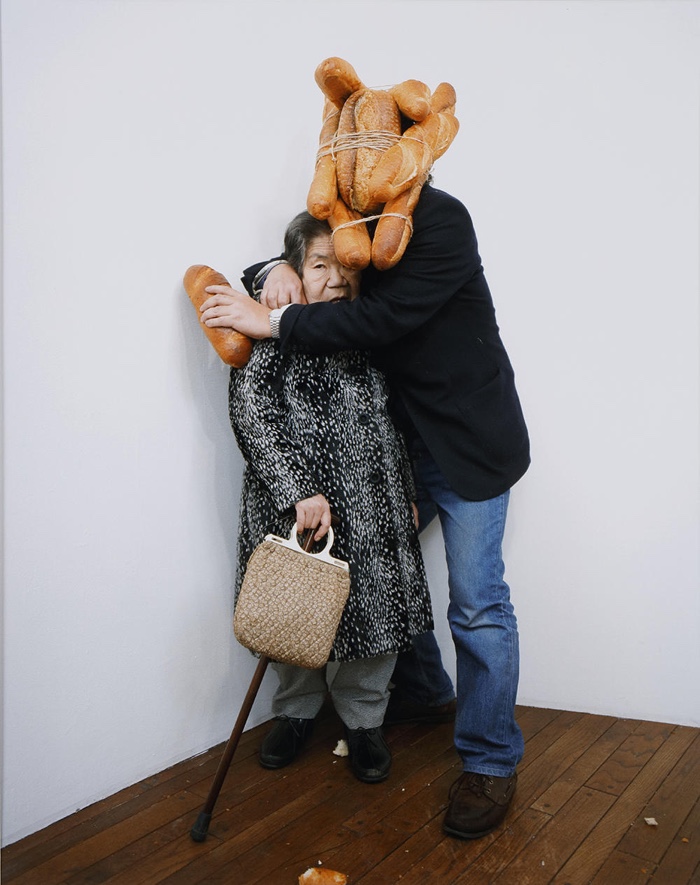

Ni Haifeng, Self-Portrait as a Part of Porcelain Export History (no. 1), 1999–2001

Ni Haifeng painted his torso with the kind of motifs that 18th-century Dutch traders designed to satisfy Western demands for ‘china’. The words on his torso are written in the style of a museum label or a catalogue entry, a direct allusion to the traumas left by colonialism and the commodification and exploitation of human beings.

Tony Albert, Brothers (Our Past, Our Present, Our Future), 2013

Tony Albert portrays Aboriginal men facing the camera with a red target painted on their torso. The motif evokes racial profiling and state violence towards Indigenous people in Australia. In Aboriginal iconography, however, red circles represent the emanation of water ripples or sound waves – a depiction of the quality of the men’s inner spirit.

The Once Upon a Time chapter demonstrates how a single photo can encapsulate a complex story. Because of the hours, labour, actors, technicians and skills involved in reconstructing scenes capable of conveying a full narrative, the practice can sometimes take the dimensions of movie-making.

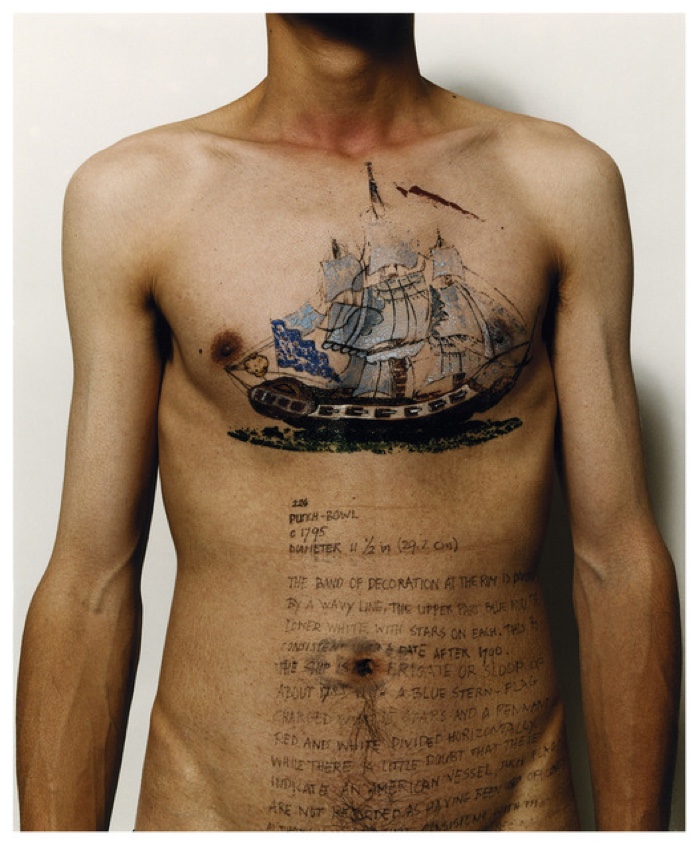

Yinka Shonibare, Diary of a Victorian Dandy: 14.00 hours, 1998

In Diary of a Victorian Dandy, Yinka Shonibare plays the main character in a sequence that depicts five moments in the daily life of an 18th-century fashionable gentleman. The work alludes to William Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress (1732–34), a series of painting that chronicled the decline and fall of the spendthrift heir of a rich merchant. Shonibare’s scenes contrast sharply with the marginalised status of black people at the time as well as with his own position as a creative black man with a physical disability in contemporary Britain.

Wendy Red Star, Four Seasons – Winter, 2006

Wendy Red Star re-appropriates 19th and 20th-century colonialist representations of Native American people and cultures. Her Four Seasons series shows her wearing a traditional elk-tooth dress that identifies her Apsáalooke (Crow) ancestry. Everything around her, however, screams of artificiality. Fake backdrop, synthetic snow, inflatable wildlife and plastic surfaces. Each of these elements hints at the scenographic simulation of “natural habitat” in world’s fair enclosures, natural history museum diorama and other types of colonialist representations.

Cristina de Middel, Susan Morrison, from the series Poly Spam, 2009

Cristina de Middel gives life to some of the spam emails she receives. She stages the ‘authors’ of the messages in scenarios that are based on the description of the desperate situations they claimed to find themselves in. The artist would also sometimes write the scammers to get more details about their circumstances.

.

The Deadpan section zooms in on art photography devoid of any visual drama or hyperbole. The images often invite the viewer to contemplate the interconnections between the manmade and natural world.

Richard Misrach, Wall, Near Los Indios, Texas, 2015

In Wall, Near Los Indios, Texas, Richard Misrach singles out a disconnected portion of the ‘border wall’ standing pitifully on a small patch of grass. The image suggests the lunacy of constructing a continuous wall through the 2,000-mile border terrain when the very people that the construction is meant to deter are not discouraged from crossing the border but are in fact taking even more risks to do so.

Something and Nothing shows how contemporary photographers transform the most ordinary objects and spaces into extraordinary, atmospheric images that elicit a sense that the most familiar scenes deserve more consideration.

John Lehr, Neon Rose, 2010

Tim Davis, McDonalds 2, Blue

Fence, 2001. From the series Retail

Tim Davis’s series Retail zooms on the windows of American suburban houses. At night, the glass reflects the neon signs from fast-food joints. Consumer culture quietly invading domestic life.

Intimate Life concentrates on personal relationships. Moving and intimate, they have an air of spontaneity.

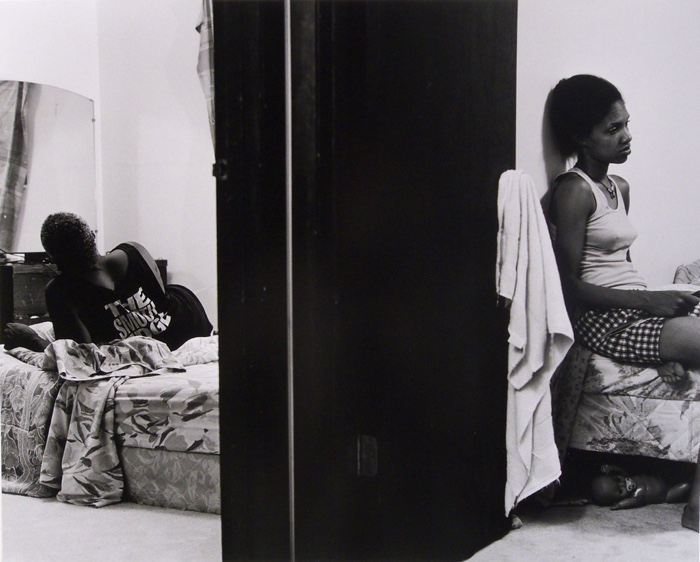

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Me and Mom’s Boyfriend Mr. Art, 2005. From series The Notion of Family

LaToya Ruby Frazier’s family scenes are subtly exploring the legacy of racism and economic decline in Braddock, a small town in Pennsylvania.

Richard Billingham, Untitled, 1994. From the series Ray’s A Laugh

Richard Billingham, Untitled, 1994. From the series Ray’s A Laugh

Richard Billingham, Untitled, 1994. From the series Ray’s A Laugh

Richard Billingham, Untitled, 1994. From the series Ray’s A Laugh

Charlotte Cotton illustrate each photographer with one photo only. I don’t have to. Ray’s A Laugh is perhaps my favourite photo series ever. I find it moving, brutal, funny, arresting. I’ll never get tired of it. In the early 1990s, Billingham started recording the life of his parents in their tower block home in the West Midlands. His dad drank too much. His mother loved tattoos and jigsaws. She often looks angry. For some reason, I see tenderness in the photos.

The Moments in History chapter propels documentary works into the world of contemporary art.

Sophie Ristelhueber, Iraq, 2001

Sophie Ristelhueber’s images of Iraq in 2000 and 2001 brings the grim reality of war into focus. Post-battle landscapes made of sand and burnt tree stumps act as metaphors for loss of life and ecological destruction.

Patrick Waterhouse, Hip-Hop Gospel and Tanami. Restricted with Athena Nangala Granites, 2016. From the series Restricted Images: Made with the Warlpiri of Central Australia, 2018.

Working with members of the Warlpiri language group, in Yuendumu and Nyirripi communities in Australia, Patrick Waterhouse invited his collaborators to “correct” his black and white prints using dot painting traditional to these Aboriginal cultures, symbolically addressing the colonial legacy of photography in the country.

John Edmonds, America, The Beautiful, 2017. From the series Du Rag

John Edmond’s America, The Beautiful is part of a series inspired by the do rags worn by young men of colour in Brooklyn. The image shows the painterly use of light, composition and colour that characterises his portraits of masculinity.

Revived and Remade brings to light practices that build upon and play with well-known codes and icons of photography.

Christopher Williams, Kodak Three Point Reflection Guide, © 1968 Eastman Kodak Company, 1968. (Corn) Douglas M. Parker Studio, Glendale, California, April 17, 2003, 2003

Christopher Williams explores the presence of corn byproducts in countless objects and aspects of our daily lives, including in photography itself: a corn byproduct is included in the lubricant used to polish photo lenses and another can be found in the chemicals used for fine art prints. Corn byproducts were even used to make the artificial corncobs in the image above. Corn and photography are therefore both the subject and the material of his photograph.

Anchored into digital culture, the Photographicness section showcases image-based works that draw upon sculpture and painting concepts.

Soo Kim, The DMZ (Train station), 2016. From the series The DMZ

The DMZ (a name that Demilitarized Zones) is a series of double-sided works that viewers can contemplate from both sides. Soo Kim captured the border of North and South Korea at a train station that was designed to move people between the two States but has never been opened nor used.

A couple more images for the road:

Antoine Catala, Image Families, 2013

Catherine Opie, Flipper, Tanya, Chloe, & Harriet, San Francisco, California,

1995

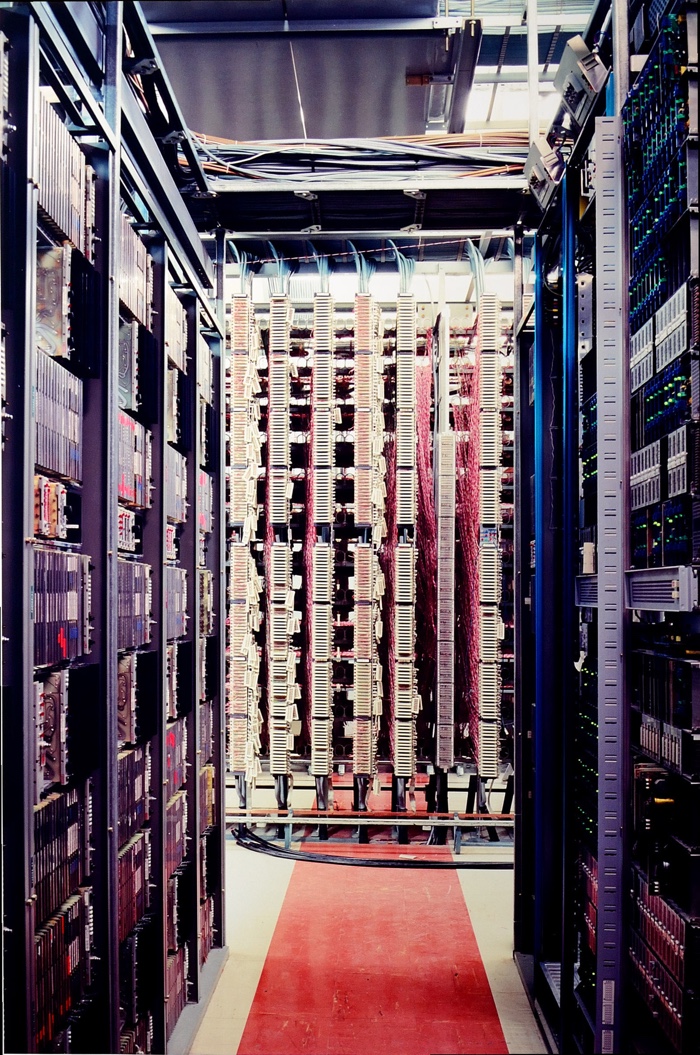

Lewis Baltz, Power Supply No. 1 (National Center Meteo, Grenoble, France), 1989–92