A few weeks ago, I took the train to Aosta. I had walked through the small Alpine city once before. That was many many years ago. It was cold, tourists were eating all sorts of dried meat and I was on my way to Turin which, to me, was one of the most glamorous destinations in the world. The Italian thriller Rocco Schiavone (a tv series that tells the story of a vicequestore from Rome transferred to Aosta as a punishment) seemed to confirm my very poor impression. A couple of weeks ago, however, i saw an ad in an art newspaper for The Families of Man at Aosta’s Museo Archeologico Regionale.

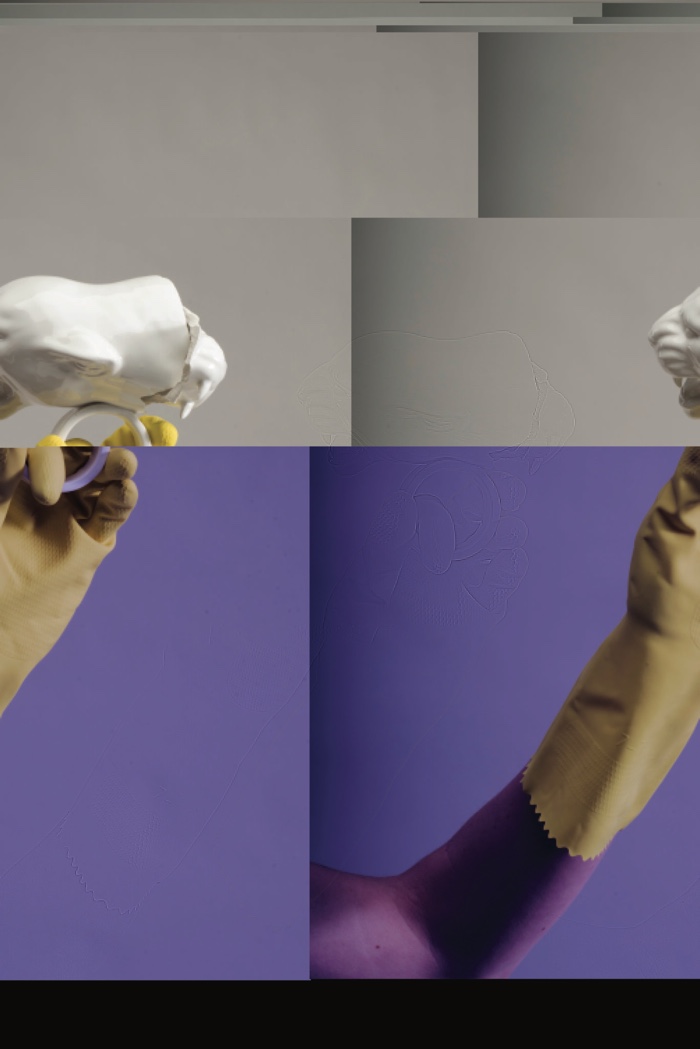

The Cool Couple, Homo Naledi – Time Travel Stuff, 2018

Andrea Galvani, Death of an Image #5, 2005

Francesca Catastini, Petrus 08, 2016

I ended up spending a fantastic afternoon in Aosta. There were still too many tourists but it was sunny, vegan-friendly and the view on the surrounding mountain was very appeasing. As for the exhibition, it is a homage to The Family of Man curated by Edward Steichen in 1955. Bringing together hundreds of images by photographers from around the world, the exhibition took the form of a photo essay celebrating the universal aspects of the human experience.

The Aosta version showcases only Italian photographers who, over the past 30 years, have been exploring the major themes of humankind and society, from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the ongoing pandemic.

The narrative of the exhibition is articulated around two main strands. One is chronological: 1989-2000; 2001-2019; 2020. The other is thematic and reflects on the most significant developments that shaped society over the 3 decades: digital technology, mass urbanisation, gender politics, climate emergency, etc. And of course the pandemic.

The exhibition is grounded in the Italian experience but many of the themes it covers transcend borders and cultures.

If you’re curious about Italian photographers’ perspective on society, here’s a brisk walk through the show:

Ferdinando Scianna, Silvio Berlusconi, 1986

I had to start with the photo of Silvio. Because of that smug smile, because it was one of the first images in the exhibition and because, as this absolutely not heavily photoshopped photo of the man taken 35 years later demonstrates, he hasn’t aged a year. And of course because Ferdinando Scianna is an extraordinary photographer.

Although I know Italy is quite the catholic place, I was surprised by the strong presence of religion in the exhibition.

Armin Linke, St. Peter’s Basilica. Investiture ceremony for a bishop, Città del Vaticano, 2002

The image above is part of Armin Linke‘s Il Corpo dello Stato/The Body of the State, a series that makes more tangible the otherwise inaccessible places in which religious and political power is exercised, where decisions are taken and ceremonies performed.

Gianni Fiorito, Jude Law in The Young Pope by Paolo Sorrentino

The shot from the tv series The Young Pope underlines with irony the need for some of the world’s oldest religions to embrace changing ways of life and modes of thinking of their subjects.

Nicolò Degiorgis, from the series Hidden Islam – Islamic makeshift places of worship in North-East Italy, 2014

While Minke’s Investiture ceremony for a bishop shows a ritual built upon pomp, traditions and spectacular architecture, Muslims living in Italy often struggle to find space where they can practice their religious culture.

In Hidden Islam, Nicolò Degiorgis mapped makeshift Islamic places of worship located across the northern regions of the Veneto, Friuli Venezia Giulia, Trentino and South Tyrol. The series documents the geography of a religion forced to exist secretly because, despite the fact that 4,9% of the Italian population is muslim, Islam has not yet officially been recognised by the State.

Nicola Lo Calzo, The (in)visible man, from the series Binidittu, 2017-2020

The bearers of the statue of Benedict during the vigil procession that takes place in September of each year in San Fratello, birthplace of Benedict in 1524.

Nicola Lo Calzo, from the series Binidittu, 2017-2020

My favourite photo however was by Nicola Lo Calzo. Binidittu (San Benedetto il Moro in Italian, Saint Benedict the Moor in English), born in Sicily in 1524 from two enslaved Africans, became the first Modern black saint in history. From the XVIIth century onwards, however, the popular saint was gradually invisibilised. His background and skin colour reminded people of some of the less palatable episodes of the history of Sicily, namely slavery and sugar plantations. His gradual removal from the Western imagination resonates strongly with the experience of the African diaspora in the Mediterranean.

For the photographer, the black saint became the pretext to reflect non only on the colonial past of the island and on today’s migration but also on the transformation of myths and beliefs.

Adrian Paci, Centro di permanenza temporanea / Temporary Reception Center, 2007

An Albanian who emigrated to Italy, Adrian Paci has long been exploring issues of displacement and uprootedness. The photo comes from a famous video showing migrant men and women walking up the boarding steps of a plane. As the camera pans out, however, it becomes apparent that the stairs are not attached to any vehicle. Flights in the background land and take off but these people will stay on the tarmac. Immigrant day labourers, some illegal, were cast to shoot this video. The workers were themselves trapped in a perpetual state of employment uncertainty.

Although the work was filmed at San José airport in California, it takes its title from the Italian term for the Italian detention centres that house illegal immigrants and refugees until their cases have been solved. Which can take years. Another uncomfortable detail about the work is that Paci momentarily hired these workers for the film, which made him complicit in the system he critiques.

Massimo Vitali, Viareggio Red Fins, 2000

Massimo Vitali never tires of photographing busy beaches. His use of light overexposures and pastel colours makes banal scenes of family at the beach sublime. And although the images look carefree, there is a sociological motivation behind them. “I was testing my 8×10 camera in 1994, and Berlusconi had just won the elections,” he told W magazine. “I was curious about the Italians who had voted for him, and so, while testing the camera, I decided to put my scaffolding in the sea and look back at the people.”

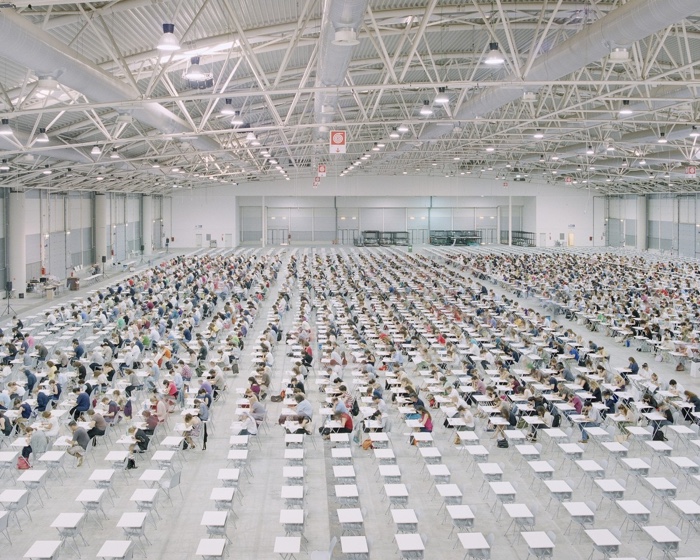

Michele Borzoni, Fiera di Roma, 2016

The photo above is part of a series that explores the search for a permanent position in the Italian public service. Michele Borzoni spent four years watching these bureaucratic examinations, where thousands of young people attend oversubscribed exams that take place in sports stadiums and concert halls.

The image shows the open competitive exam for the recruitment of 40 art historians at the Ministry of Culture. 1550 people applied for the exam which took place in Fiera di Roma, a trade fair space in Rome.

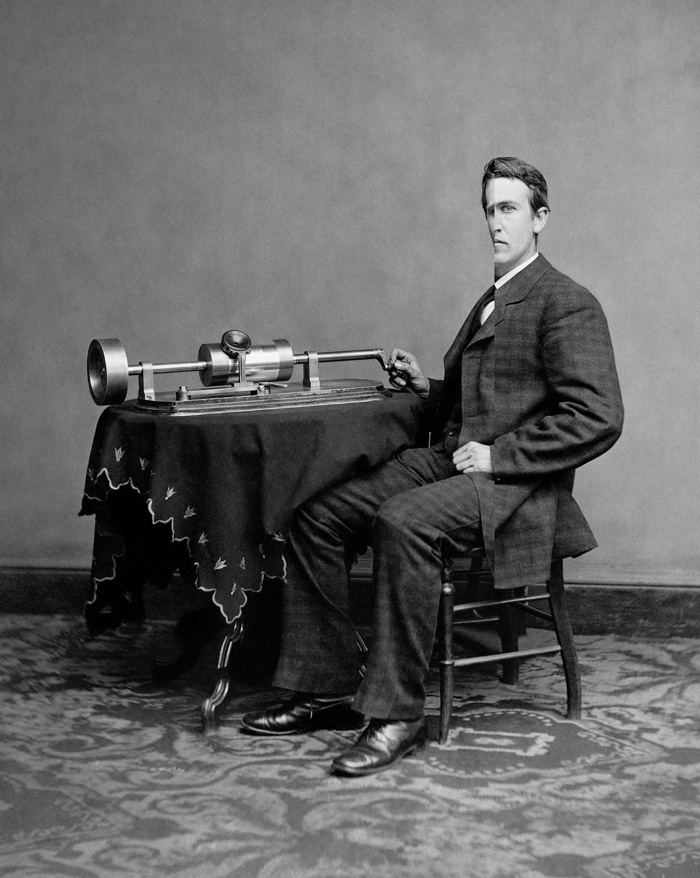

Lamberto Teotino, Sistema di riferimento monodimensionale SDRM19, 2011

Lamberto Teotino, Sistema di Riferimento Monodimensionale SDRM18, 2011-2015

Lamberto Teotino used archive images that celebrated human industriousness and progress and removed thin vertical portions from the image, forcing the observer’s eyes to try and reconstruct the missing string of visual information. The title of the series, Sistema di Riferimento Monodimensionale, is inspired by philosopher and mathematician Rene Descartes’ theorem of one-dimensional coordinate system. Teotino’s investigation on the interruption of information in space keeps the legibility of the image but adds an almost supernatural dimension to it.

Sara Benaglia, Erasure Test. C5 – Christine Rainer, 2019, Erasure Test. H6 – Mary Patrizio, 2019, Erasure Test. J7 – Daniela Falcone, 2019

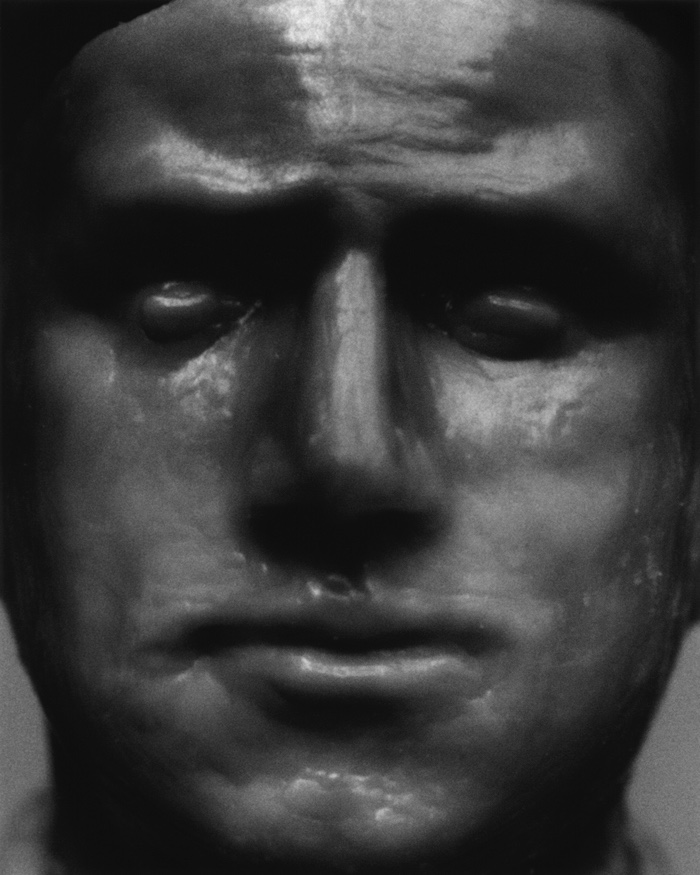

Simone Schiesari, PMHS (Post Mortem Human Surrogate) #3, 2008

Simone Schiesari explores the ambiguity of the new human images: does this face belong to a man? Why is it so waxy? Is it/he even alive?

Alberto Sinigaglia, Greenhouse George, 2017

Alberto Sinigaglia explores the ambiguity between the natural and the man-made. His clouds are actually the top part of atomic mushrooms

Gianni Berengo Gardin, Venezia, Una grande nave mentre attraversa il canale della Giudecca, 2013-2014

In 2012 and 2014, Gianni Berengo Gardin portrayed the daily arrival and departure of large cruise ships in the Venetian lagoon. The impact the sea monsters are having on the city is obscene. The cruise liners not only dwarf the architecture, they are also sources of pollution and damage to the lagoon and to the foundation of buildings.

Italy has finally put the demands of residents and cultural organisations above those of the tourist industry by banning the cruise liners from the Venice lagoon but the move came after years of protests and promises. A documentary called Gianni Berengo Gardin’s Tale of Two Cities explores the fragility of the laguna and demonstrates that business as usual and progress at any cost have become outdated and dangerous paths to follow.

Paolo Woods and Gabriele Galimberti, The Heavens, 005, 2015

Press articles about tax havens are often illustrated with images of anonymous beaches covered in white sand and coconut trees. With The Heavens, Paolo Woods and Gabriele Galimberti lift the lid on these furtive jurisdictions, their idiosyncrasies, players and apparatus. The photographic investigation features the usual suspects: the Cayman Islands, Singapore, the City of London, Luxembourg, etc.

Alex Majoli, Scene #7588, 02/03/2020

In an E.R. in the northern city of Reggio Emilia, a paramedic sprays down hospital beds. Along with Lombardy, the Emilia-Romagna region has been among the most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Armin Linke, Honda Research Centre, humanoid robot, Wako (Tokyo), 1999

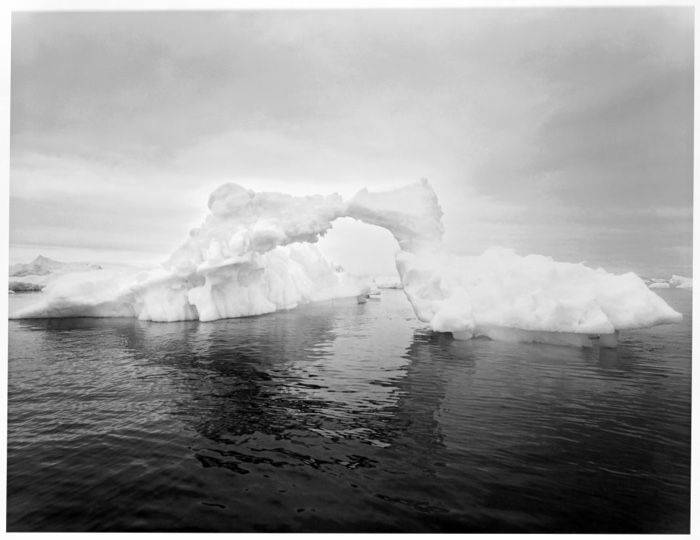

Francesco Bosso, Diamond #4, 2015, Greenland

Mario Dondero, Il mondo di Piero della Francesca, contadino della regione di Sansepolcro, 2002

Mattia Paladini, Valtournenche, 2020

The Families of Man was curated by Elio Grazioli and Walter Guadagnini (someone who seems to curate every single important photo exhibition in Italy at the moment.) The show remains open at the MAR – Museo Archeologico Regionale di Aosta/Regional Archaeological Museum of Aosta until 10th October 2021.