Survival of the Fittest at Kunstpalais in Erlangen. An exhibition that’s only one hour away by train from Munich and one of the last shows i got to see before the coronavirus put Europe on lockdown…

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, Self-inflating Antipathogenic Membrane Pump from Designing for the Sixth Extinction, 2013-15

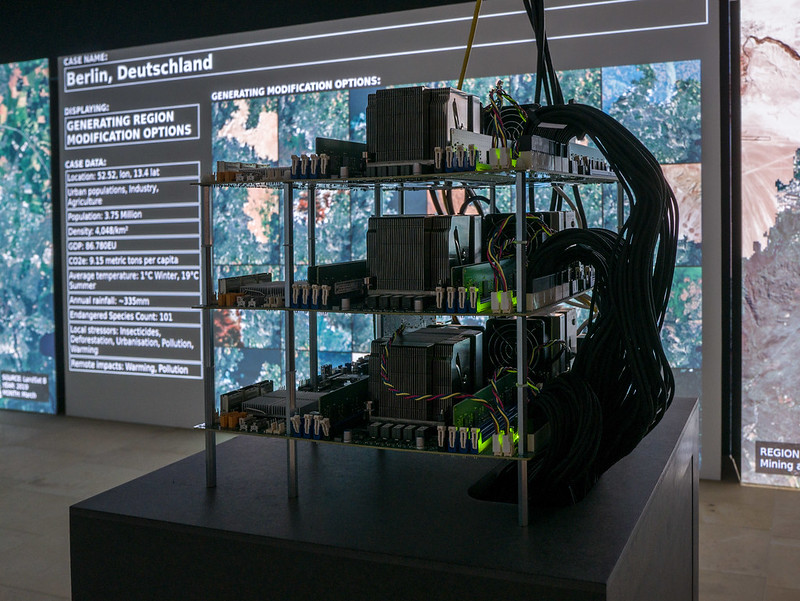

Tega Brain, Julian Oliver and Bengt Sjölen, Asunder, 2019. Exhibition view at Kunstpalais Erlangen, “Survival of the Fittest.“ Photo: Kunstpalais Erlangen, Alexandre Karaivanov

Are artificial intelligence, blockchain technology, bioengineering and other innovations a key to healing the planet or are we fooling ourselves? Survival of the Fittest -which title seems to unintentionally mock current events- helps us ponder upon this question.

The installations, videos and sculptures selected by curator Milena Mercer look at the ambiguous role that technology can play in shaping the future of our planet. Each in their own way, these artworks navigate the tensions between a techno-solutionist discourse that celebrates technology as the ultimate answer to the effects of climate change and, on the other hand, the more critical voices that see in our faith in technology one of the main drivers of the ecological crisis.

In the Darwinian evolutionary theory, the “survival of the fittest” can be understood as the “survival of the form that will leave the most copies of itself in successive generations.” In the age of digital technology and synthetic biology, the fittest might not be the one we are used to: a feline Ai might turn out to be the fittest politician to help a city face the challenges tomorrow will bring; an ammonite that is 66 million years old might be the best harbinger of our future; and a lab-engineered life might be the best-adapted organism to survive the climate crisis.

Art, unlike design or technology, doesn’t promise to solve problems but its value is unrivalled when it comes to articulating difficult questions, bringing nuances to bold promises and helping us reflect on a future we can’t seem to trust anymore.

Here’s a quick tour of the show:

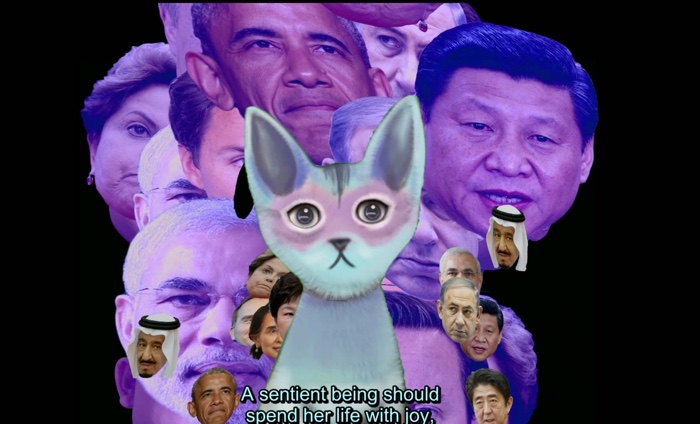

Pinar Yoldas, The Kitty Al: Artificial Intelligence for Governance (film still), 2016

Pinar Yoldas, The Kitty Al: Artificial Intelligence for Governance (film still), 2016

It’s hard to resist the charm of Pinar Yoldas‘ Kitty AI. You would normally distrust it. First of all, it’s an AI. And that AI has achieved what many people fear: domination over humans. We are in 2039, Kitty AI is the first non-human governor of a big European city. It is adorable and efficient, wise and cute. Citizens use their smartphones get in touch with it and complain about what is wrong in their neighbourhood. If the Kitty AI algorithm determines that the issue is important, it will solve the problem immediately.

What makes Yoldas’ animation particularly smart is that it doesn’t just propel us into speculation, it charts the various socio-political events and technological landmarks that led citizens to elect an AI to rule their city.

Simon Denny, Extractor, 2019

Simon Denny, Extractor (Digital illustration by Paul Riebe), 2019

Simon Denny, Caterpillar Biometric Worker Fatigue Monitoring Smartband Extractor Pop Display, 2019. Photo: Jesse Hunniford/MONA

Simon Denny‘s series of works uncovers different layers of extractive behaviours, most of them spurred by the greed of the corporations that mine, engineer and manufacture digital technologies but also collect and process vast amounts of data, doing untold damage to ecosystems in the process.

The first thing you see as you enter the room is an over-sized cardboard version of CAT’s smartband, a bracelet that monitors worker’s sleep and determine the likelihood of an accident on construction or mining sites caused by fatigue. The device ensures that a worker’s weariness will not jeopardise productivity and profitability. The smartband is used in the mining industry, the backbone of the economy in many countries but also a cause of disasters and pollution that ravage ecosystems and the health of local communities.

The large cutout serves as a display for dozens of boxes containing a sinister version of the 1960s Australian board game Squatter, a kind of outback sheep-farming version of Monopoly. In the original game, players are aspiring farmers who battle flood damage, bushfires, animal disease, droughts and other disasters that have since become the new normal for Australia and other countries.

Denny’s version of the game -called Extractor– transposes the principles of sheep farming to the lucrative industry of data mining. At the start of the game, each player is a small start-up operator dreaming of amassing and monetising as much data as possible. The obstacles faced by players face range from diversity training to staff walkouts due to military contracts.

The game also demonstrates that mining for data is just as damaging for the planet as mining for raw material. Everything is connected, the virtual economy has very physical and ecological dimensions.

Christina Agapakis, Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg and Sissel Tolaas, Resurrecting the Sublime in Better Nature, 2019. Exhibition view “Survival of the Fittest”, Kunstpalais Erlangen. Photo: Alexandre Karaivanov

Christina Agapakis, Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, Sissel Tolaas, Digital reconstruction of the extinct Hibiscadelphus wilderianus Rock, on the southern slopes of Mount Haleakala, Maui, Hawaii, around the time of its last sighting in 1912. Part of Resurrecting the Sublime, 2019

Resurrecting the Sublime offers visitors the opportunity to smell extinct flowers, lost due to colonial activity. The scent installation is the result of a collaboration between designer Dr. Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, smell researcher and artist Sissel Tolaas and an interdisciplinary team from the biotechnology company Ginkgo Bioworks, led by Creative Director Dr. Christina Agapakis.

Using DNA extracted from specimens of flowers stored at Harvard University’s Herbaria, the Ginkgo team used synthetic biology to predict and resynthesize gene sequences that might encode for fragrance-producing enzymes. Based on Ginkgo’s findings, Sissel Tolaas reconstituted the flowers’ smells in her lab, using identical or comparative smell molecules.

You can sit on a stone under a hood that releases the scent and watch an animation showing the landscape as it used to be when the flower was still blooming. The project replicates the feeling of being there but it can never reproduces the full sensory experience. Once a species has disappeared, its ecosystem reconfigures itself. We can never go back in time and undo the damage we’ve done to the planet.

This kind of project lays bare the contradictions within the whole de-extinction movement. In a time of global biodiversity crisis, it would be wonderful to bring back the wholly mammoth and other vanished wild animals and plants. But which species should we start with and which criteria should we use to determine our priorities? Cuteness of a species? Amount of “services” it can fulfil in the environment? And if we manage to “resurrect” a tree or an animal, how will they fare if their original ecosystem has changed? Could they, for any reason we haven’t foreseen, constitute a threat for modern ecosystems? Is the original cause of their extinction still present? How do we ensure that the recreated species is genetically-diverse enough to ensure its own survival in the long term?

Resurrecting the Sublime, however, also suggests that the knowledge we are gaining from figuring out how to bring back extinct species could have a positive effect on the wildlife that is still around us: by connecting us to it and make us realise what we might loose.

Jonas Staal, Neo-Constructivist Ammonites, 2019. Exhibition view “Survival of the Fittest”, Kunstpalais Erlangen. Photo: Alexandre Karaivanov

Public and increasingly also public interests are intent on colonising Mars and possibly other planets in the coming decades in a bid to flee from climate catastrophe, spread capitalism to interstellar levels, satisfy a thirst to conquer what hasn’t been conquered yet, mine for resources that are becoming harder and harder to extract on planet Earth, etc.

With his project Interplanetary Species Society (ISS), Jonas Staal invites us to consider our own biosphere before we go and embark on this ambitious project of becoming an interplanetary species.

ISS calls for new forms of comradeship between human, non-human, and more-than-human agents. Cooperation instead of colonisation! His installation consists of drawings and of ammonite fossils on top of columns bearing slogans such as “Redistribute the Future”, “Fossils are Comrades not Fuel”, “Collectivize Extinction” and “Living Worlds”. His Neo-Constructivist Ammonites installation pays homage to the Russian constructivists and productivists that spoke of revolutionary objects as “comrades”, as revolutionary agents in their own right. Ammonite fossils are thus comrades. The extinct marine mollusc animals dominated the earth’s oceans until it perished in the 5th mass extinction. The human species is now facing the unfolding of the 6th mass extinction of their own making. So maybe ammonites can teach us something. They are fossils; we are fossils-in-the-making.

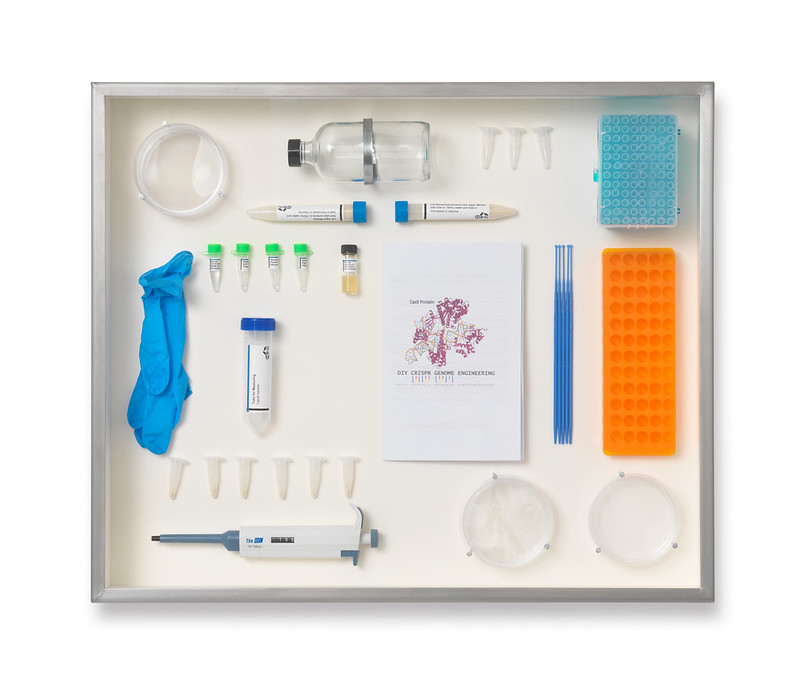

Andreas Greiner, Edit Yourself KIT, 2018. Photo: Jens Ziehe

Andreas Greiner and Páll Ragnar Pálsson, Aussaat, 2019. Installation view at Kunstverein Heilbronn. Photo: Jens Ziehe

Andreas Greiner and Páll Ragnar Pálsson, Aussaat, 2019. JCVI-SYN3.0 Zell landscape SEM

In 2016, scientists engineered a fully synthetic bacterium containing the smallest genome of any self-replicating organism. Made of the 473 genes, the so-called JCVI-syn3.0 includes only the genes essential for life. John Craig Venter calls them the first complete human-made life and the ‘beginning of digital biology’.

Andreas Greiner and Páll Ragnar Pálsson‘s installation consists of a self-playing piano and a video showing a landscape of the microscopic JCVI-Syn3.0 cells. By magnifying these microscopic forms of life, the installation brings us face to face with living cells that have been entirely engineered inside a laboratory. They belong to our living world, yet they stand aside at the moment. Which status should we give them?

Pálsson composed a piece of music for piano, soprano and violin inspired by video footage of these cells as well as a poem, ‘Sterne im März’ by Ingeborg Bachmann. The musical piece plays in the room. On the wall, Greiner has framed and hung an off-the-shelf DIY CRISPR kit that promises to allow your to manipulate life “from the comfort of your own home.”

Paul Kolling, Paul Seidler, Max Hampshire, terra0 – Prototype for an augmented forest, 2016

Paul Kolling, Paul Seidler, Max Hampshire, terra0 – Prototype for an augmented forest, 2016. Exhibition view “Survival of the Fittest”, Kunstpalais Erlangen. Photo: Paul Kolling

Paul Kolling, Paul Seidler, Max Hampshire, terra0 – Prototype for an augmented forest, 2016. Exhibition view “Survival of the Fittest”, Kunstpalais Erlangen. Photo: Paul Kolling

Paul Kolling, Paul Seidler, Max Hampshire, terra0 – Prototype for an augmented forest, 2016. Exhibition view “Survival of the Fittest”, Kunstpalais Erlangen. Photo: Paul Kolling

Terra0 is a self-owning augmented forest, a prototype that aims to sell licenses to log its own trees through automated processes, smart contracts and blockchain technology. With this system the forest is in the position to accumulates capital, buy more ground and therefore expand.

Other works in the exhibition:

Anna Dumitriu & Alex May in collaboration with Amanda Wilson, Archaea Bot: A Post Climate Change, Post Singularity Life-form, 2018-2019

Futurefarmers, Fog Inquiry, University of California Berkeley, The Sea Inside the Kettle Boils, 2020. Exhibition view “Survival of the Fittest”, Kunstpalais Erlangen. Photo: Alexandre Karaivanov

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, Mobile Bioremediating Unit in Designing for the Sixth Extinction, 2013-15. Exhibition view “Survival of the Fittest”, Kunstpalais Erlangen. Photo: Alexandre Karaivanov

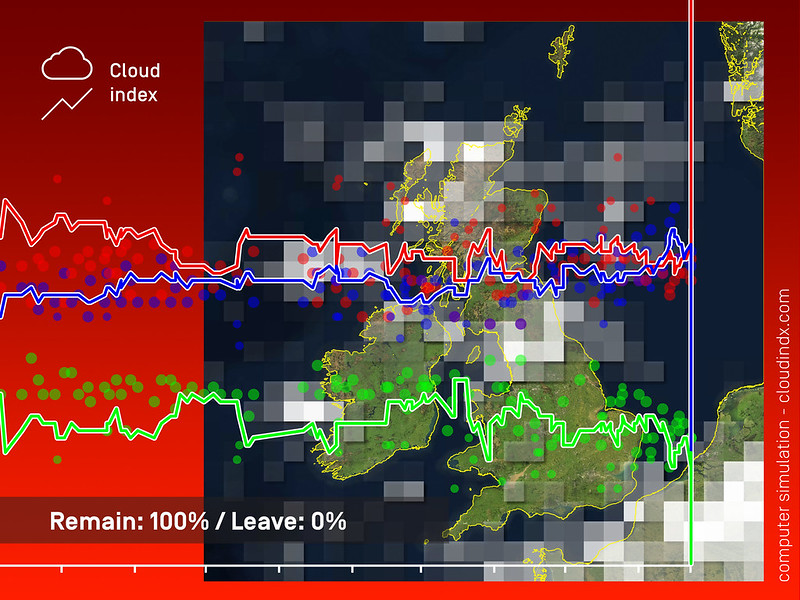

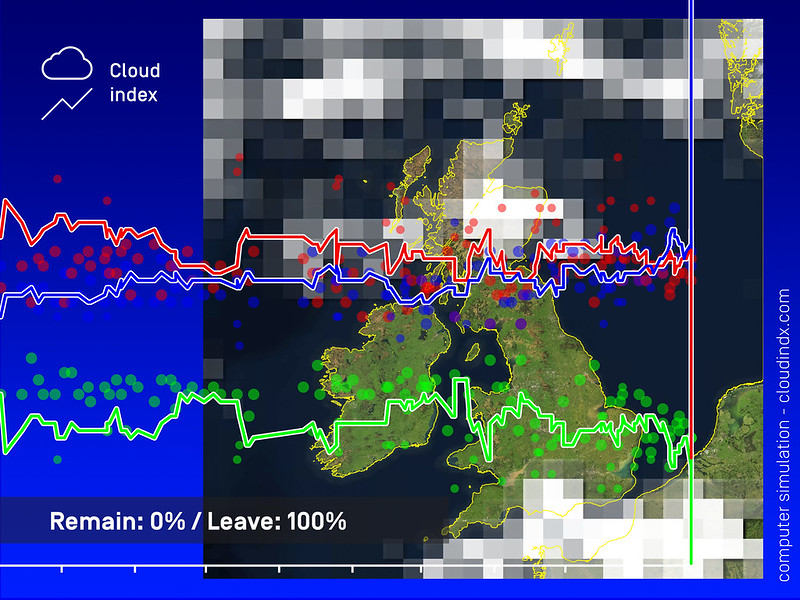

James Bridle, Cloud Index, 2016

James Bridle, Cloud Index, 2016

James Bridle, Cloud Index, 2016. Exhibition view “Survival of the Fittest”, Kunstpalais Erlangen. Photo: Alexandre Karaivanov

Simon Denny, Extractor Screen 1, 2019. Photo: Jesse Hunniford/ MONA

Survival of the Fittest will reopen on Friday 15 May at Erlangen Kunstpalais in Germany. The show was extended until 6 September. It was curated by Milena Mercer, curator and acting director at the Kunstpalais & Städtische Sammlung Erlangen.

Previous stories: Asunder. Could AI save the environment?, Talking broiler chicken, germ maps and maggots with Andreas Greiner, Artists Re:Thinking the Blockchain, etc.