The first few words i read on the leaflet of the Share Festival, the annual event of contemporary tech art and science in Turin, sum up so poetically the way i see the city:

Share Festival XIV, GHOSTS, is worldly by being otherwordly, is Turinese by being international, touches the heart of the matter by embracing the skin, is futuristic by being historical, is visible through the invisible, spoken through the unspeakable and alive through the spirits of the dead.

Well, that certainly beats the very cheesy title i had originally selected for my review of the festival exhibition (The Share festival. Or how to put spirits into the spirit of innovation)!

While Turin is famous -at least in Italy- for its innovations and manufacturing energy, it is also said to be the only city that is part of both the triangle of White Magic and the triangle of the Black Magic. This year the Share Festival played with this enigmatic identity and chose Ghosts as its main theme.

The works exhibited over the course of a long weekend in Turin called forth all the Ghosts of technologies and human memories.

There were 6 works in the show, each of them shortlisted for the Share Prize, each radically different from the others. Taken together though these artworks offered a compact, coherent and enchanting perspective on a technologically-mediated world in which the rational constantly contends with the paranormal and the superstitious.

Below are the 4 works i found most fascinating:

Starting with the ghost of a bird hunted to extinction….

Sally Ann McIntyre, Collected Huia Notations (like shells on the shore when the sea of living memory has receded), 2015. Image courtesy of the Share festival

Sally Ann McIntyre, Collected Huia Notations (like shells on the shore when the sea of living memory has receded), 2015

The Huia is an extinct species of wattle bird from New Zealand. The male and the female had differently shaped bills. They worked together to feed on wood-burrowing larvae, the male chiseling the bark from trees, while the female removed exposed grubs with her long, curved beak. The arrival of European settlers led to the loss of their habitat through deforestation, the introduction of new predators and the mass killing of the birds in 1901 when their feathers sparked a fashion craze on the old continent. The last officially recorded Huia was seen in 1907.

There is no direct recording of their songs. However, in 1949, a farmer named Robert Batley asked Henare Hāmana, a local Māori who used to lure huia by imitating their call, to accompany him to Wellington and record his imitation of the bird on a disc.

Sally Ann McIntyre‘s Collected Huia Notations (like shells on the shore when the sea of living memory has receded) calls forth the ghost of the lost bird.

She first asked Pascal Harris in Dunedin, New Zealand, to play on the piano the four known Western musical notations of the song of the Huia. The sounds were then inscribed onto phonograp wax cylinder by Graham McDonald of the National Film and Sound Archives in Canberra. The artist chose the piano because it was a musical instrument found in most domestic houses in colonial New Zealand and the wax cylinders because they were the only commercially available sound recording technology available while the Huia was still alive. During the exhibitions of the work, the sounds are played on an Edison Gem phonograph, launched on the market in 1899 for domestic use.

However, the wax cylinders are so fragile that each playback is a small erosion of the recording, suggesting that the bird will continue to escape from our understanding with each attempt to retain the memory of its existence.

It is hard not to see in this work an allusion to the 1,200 animal species which, scientists warn, “will almost certainly face extinction” without conservation intervention.

Casey Reas, The Untitled Film Stills. Image courtesy of the Share festival

Casey Reas, The Untitled Film Stills. Image courtesy of the Share festival

The Untitled Film Stills is part of Compressed Cinema, a body of work in which Casey Reas uses generative adversarial networks (GANs.) GANs are a type of machine learning systems in which two neural networks contend with each other and generate images indistinguishable from photography.

The artist reinserts a certain level of human agency and creative control into the mechanism by selecting the images GANs trains on. Instead of employing the technology to create realistic images, Reas thus deviates it from its main function, stretches GANs creative potential even further and explores its ability to produce uncanny images.

Each image in The Untitled Film Stills series appears grainy and a bit blurry, as if it were a frame from an imagined film that might have been rescued from the past.

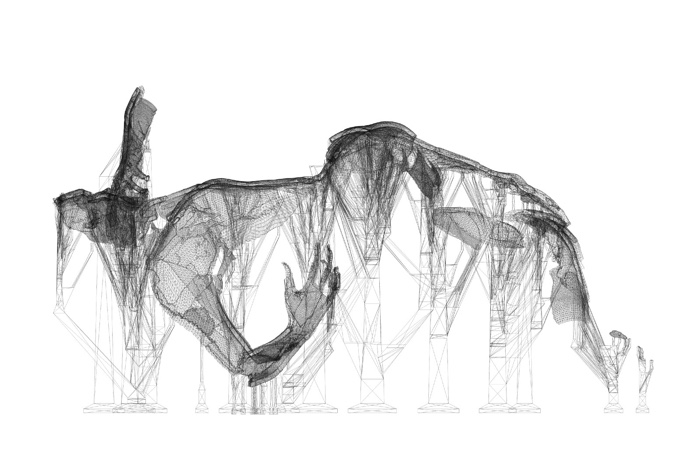

Sophie Kahn, Machine for Suffering. Image courtesy of the Share festival

Sophie Kahn, Machine for Suffering

Sophie Kahn, Machine for Suffering

Sophie Kahn’s work explores how science and technology scrutinize and eventually misinterpret the human body.

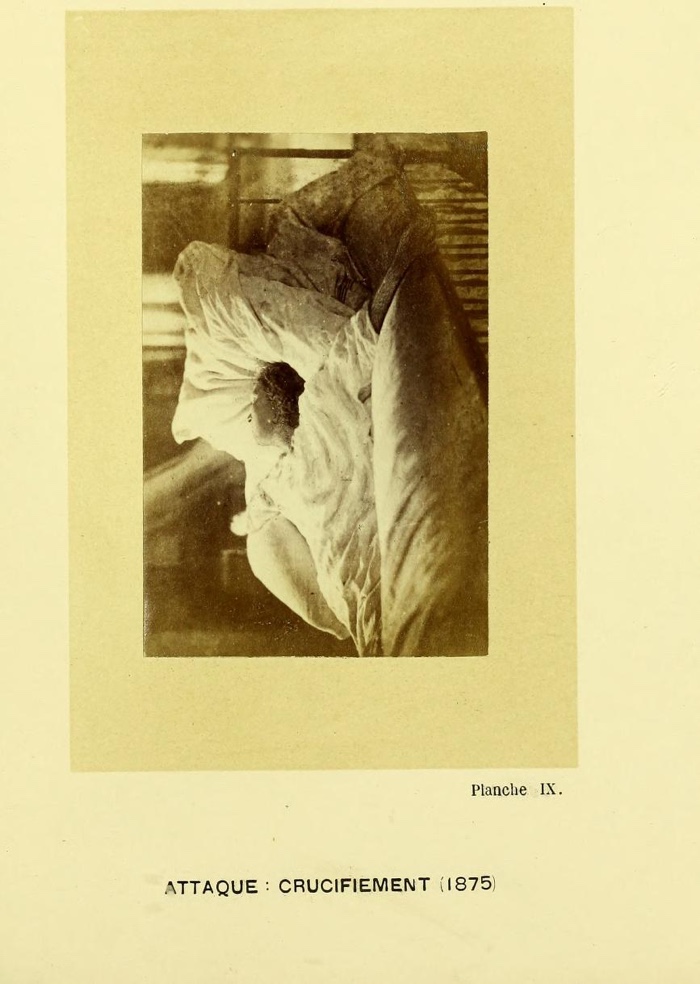

The artist uses a laser scanner to captures performers reenacting poses from photos that were developed to diagnose and record hysteria in the 19th Century. Neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot was then studying hysteria with the help of anatomical artist Paul Richer at the Salpêtrière hospital in Paris. Together, they elaborated charts and images documenting the physical poses they regarded as “typical” of the various phases of an attack of hysteria. Photography was their medium of choice, even though photos could obviously not capture the underlying psychological cause(s) of what ailed their patients. Interestingly, hysteria was a psychiatric diagnosis that, at the time, was applied largely to women. Just like today the adjective “hysterical” is almost consistently used to describe women who dare to express themselves with a bit of anger or passion.

Image from Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière, 1876-80

Sophie Kahn, Machine for Suffering. Image courtesy of the Share festival

Similarly to what happened in the 19th Century with photography, the 3D technology Kahn is using today fails to adequately capture its human subjects. Since the scanners aren’t designed to handle movements, let alone emotions, they get confused by the ever-changing spatial coordinates and turn the female bodies into glitchy shells that the artist paints, sands, glues and props up with scaffolding.

Her Machines for Suffering look like bodies that had been broken down then hastily pieced back together.

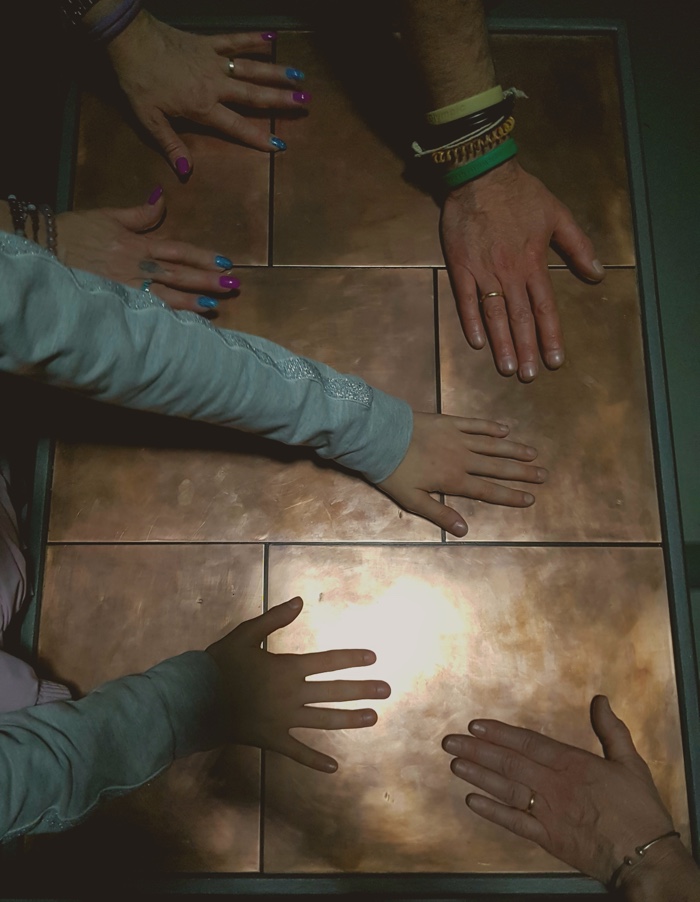

Fanni Dada, Segnali dal futuro. Image courtesy of the Share festival

Fanni Dada, Segnali dal futuro. Image courtesy of the Share festival

Fanni Dada, Segnali dal futuro. Image courtesy of the artists

Segnali dal futuro, by the Italian duo Fanni Dada, evokes a future that comes back to haunt us. This might sound paradoxical but some of the most worrying characteristics of our epoch (from man’s capacity to destroy himself with the technology he creates to the mass extinction of sepecies) were described with disturbing accuracy in the works of J. G. Ballard and Aurelio Peccei. I’m not going to insult you by giving you a bio of the iconic science fiction writer but Peccei might need a few lines of intro.

Peccei, born in Turin (a great place to be as the whole team of the Share festival and i will tell you), was the co-founder with Alexander King of the Club of Rome, an international group of people from the fields of academia, civil society, diplomacy and industry who met to reflect on the interconnectedness of a series of issues that, until then, had been examined separately and in a short-term framing: environmental deterioration, the depletion of natural resources, poverty, endemic ill-health, criminality, etc. Their conclusions, published in 1972 under the title The Limits to Growth, suggested that economic growth could not continue indefinitely if humanity continued plundering resources as it was already doing. Many of their concerns and recommendations feel painfully prescient today. And almost 50 years after their first meeting in Rome, it appears that we’re still governed by the same irresponsible mechanisms and ideologies.

Visitors of the festival were invited to place their hands on the copper plates connected to the electrical impulses of the installation video signals. This simple gesture seemed to conjure the spirits of the two forward-thinking figures. Like in a séance, their faces appeared to urge us to reflect on the kind of future we’ve already wasted and the future we might still hope for today.

Well, we didn’t listen to scientists, artists and philosophers then and we still foolishly ignore their warnings now. It doesn’t sound so far-fetched to ask ghosts to shake us our of lethargy and complacency.

The jury for the SHARE Prize was composed by Andrea Griva from the School of Entrepreneurship & Innovation, artist Lia; curator and art critic Domenico Quaranta; writer, activist and Share Prize curator Jasmina Tesanovic and science-fiction author and Share Festival artistic director Bruce Sterling.