Interest in shamanism is expanding faster than any other spiritual practices in the Western world. In England and Wales alone, the number of people saying they practice has risen from 650 in 2011 to 8,000 in 2021.

Perhaps these numbers shouldn’t surprise me as much as they did. While techno-sciences are expanding the physical and intellectual limits of the human body, more and more people are wondering what it means to be human. Why COVID has claimed so many victims. Why there seems to be so little we can do to control the catastrophic effects of climate breakdown. Or why those same innovations do not guarantee the everlasting survival of the human species on planet Earth. If they are losing faith in a bright future, perhaps it is only natural that many people look for deeper connections with spirits and the earth.

Shamans. Communicating the invisible. Exhibition view

at Palazzo delle Albere, Trento. Photo: Matteo De Stefano

Shamans. Communicating the invisible. Exhibition view

at Palazzo delle Albere, Trento. Photo: Matteo De Stefano

As the exhibition Shamans. Communicating the Invisible demonstrates, the art world didn’t wait for my two-cent analysis of the rise of shamanism to immerse itself in the world of shamanism and other spiritual practices. The show, which opened a couple of weeks ago at the rather beautiful Renaissance villa-fortress Palazzo delle Albere in Trento (Italy), examines shamanism under the lenses of anthropology, psychology, archaeology and contemporary art.

The first floor of the museum is occupied by the anthropological section of the exhibition. It takes visitors through the shamanic histories, places, rituals, languages and objects from Mongolia, Siberia and China. The works and short video interviews of scholars approach questions such as: What is shamanism? Who are the shamans and what roles do they traditionally fulfil in their communities? Can they still play a role in today’s society? Can we consider these figures to be the oldest mediators between humanity and nature? What is the meaning of their rituals and attire? How do they reach altered states of consciousness? What type of contact do they establish with the animal world?

One section of the exhibit even investigates the connections between shamanism and the anthropocene, explaining how environmental and climate disasters can be attributed to the unbalance between humankind and the environment. This unbalance often has its origins in inappropriate human behaviour towards the entities that populate non-human realms. That is where shamans come in with rituals designed to appease the spiritual beings and restore balance.

David Aaron Angeli. Shamans. Communicating the invisible. Exhibition view

at Palazzo delle Albere, Trento. Photo: Matteo De Stefano

Joseph Beuys, with Buby Durini, Difesa della natura/Grassello. Shamans. Communicating the invisible. Exhibition view

at Palazzo delle Albere, Trento. Photo: Matteo De Stefano

Although the anthropological chapter of the exhibition deserves far more detailed coverage, I’m going to jump right up to the second floor because it hosts works by modern and contemporary artists. The artworks on display look at ways to enter into a deeper connection with the unknowable and uncontrollable. Many do not explicitly allude to shamanism, but they use art and spirituality to look at the environment and ecology or to share southern perspectives on what technology may be.

Let’s start with Louis Henderson’s Lettres du Voyant, the most interesting video work i’ve seen in recent months…

Louis Henderson, Lettres du Voyant, 2013

Louis Henderson, Lettres du Voyant, 2013

Louis Henderson, Lettres du Voyant, 2013

Louis Henderson, Lettres du Voyant, 2013

Louis Henderson, Lettres du Voyant, 2013

Louis Henderson, Lettres du Voyant, 2013

Louis Henderson, Lettres du Voyant, 2013

Louis Henderson, Lettres du Voyant (trailer), 2013

In May 1871, aged 16, Arthur Rimbaud wrote what is now commonly called the Lettres du voyant (Letters of the Seer), two letters explaining his poetic philosophy.

The Lettres du Voyant is now also a film exploring the connections between spiritism, post-colonialism and technology in contemporary Ghana. Mixing documentary, fiction and poetry, Louis Henderson’s work introduces us to sakawa, a type of scam that combines Western African voodoo types of rituals and Internet-based fraud. Tracing back the scammers’ stories to the times of Ghanaian independence, the film proposes Sakawa as a form of resistance against neocolonial practices under the motto “Recover the gold that was stolen from us.”

The narrator of the film is a modern-day poet. He takes the viewer on a trip through a network of 3D mine shafts that lead the viewer to various locations: an artisan gold mine, a series of monuments that date back to the colonial era, an e-waste dump (the Agbogbloshie scrapyard which has since been bulldozed), a voodoo ritual that helps e-scammers gain super powers to travel through the internet, a nightclub, etc.

Throughout the journey, the character speaks about the colonial history of Ghana, of gold, of technology.

In a country stripped of its precious metals and used as a dumping ground for e-waste by Western countries, a new form of mining has emerged. Young workers strip down antiquated digital hardware not only for metal but also for credit card numbers or pictures of friends and families that can be used to make internet scams more efficient. The crafty hacking is “augmented” by Sakawa and constitutes a possibility for political resistance to new forms of Western colonialism.

Karrabing Film Collective, The Family, 2021

Shamans. Communicating the invisible. Exhibition view

at Palazzo delle Albere, Trento. Photo: Matteo De Stefano

The Karrabing Film Collective is an indigenous group that uses film and other media to articulate a network of practices and relationships with Earth, geology, ancestors, more-than-human life and visual culture.

Alternating between contemporary times in which Karrabing members struggle to maintain their physical, ethical and ceremonial connections to their remote ancestral lands and a future populated by ancestral beings living in the aftermath of extractive capitalism, The Family features Indigenous ancestral children defeating a white zombie with cheap, mass-produced dolls. The Family invites viewers to observe the colliding worlds of humans and their more-than-human ancestors in order to probe into the excesses of extractivism and other forms of settler colonisation still plaguing indigenous lands.

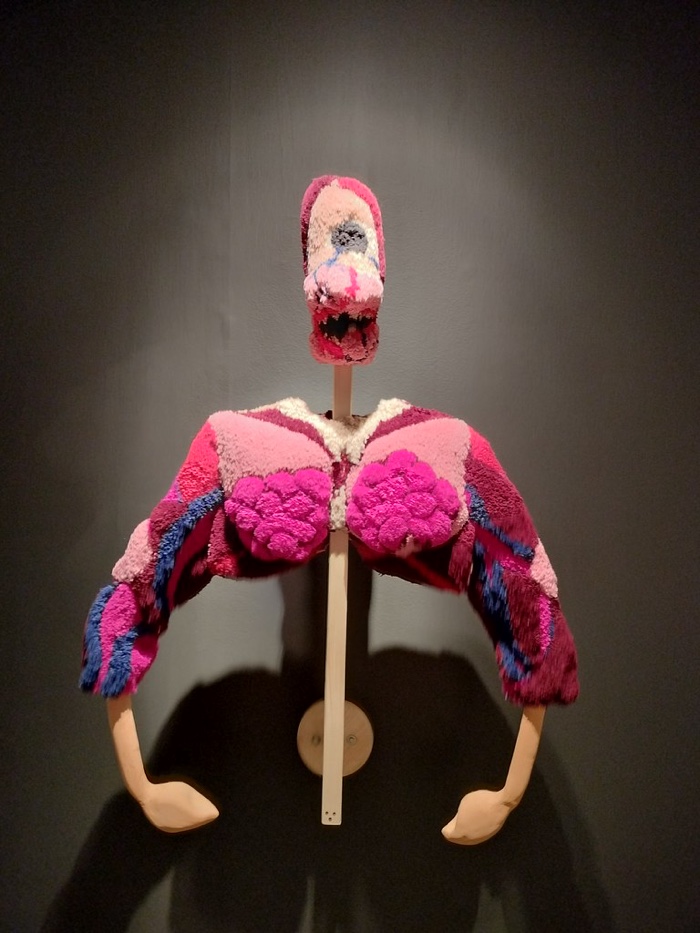

Anna Perach, Alkonost, 2019. Photo Paul Chapellier

Anna Perach. Shamans. Communicating the invisible. Exhibition view

at Palazzo delle Albere, Trento

Shamans. Communicating the invisible. Exhibition view

at Palazzo delle Albere, Trento. Photo: Matteo De Stefano

Anna Perach’s sculptures are neither humans nor beasts. Made of soft, plush fabrics, they are eerie and potentially evil. Their ambiguity only increases when you realise that many of Perach’s sculptures are designed to become alive when they are worn during performances.

The Alkonost sculpture, for example, is inspired by a legendary woman-headed bird from Slavic folklore. She was a young woman about to get married. Her future husband runs away, and she drowns herself in the river out of sadness. She comes back as a half-bird, half-woman creature. She sits on trees and sings beautiful songs that lure men, making them forget everything else.

Maria Sojob, Bankilal (El hermano mayor), 2014

Maria Sojob, Bankilal (El hermano mayor), 2014

Maria Sojob, Bankilal (El hermano mayor), 2014

María Sojob’s documentary Bankilal (El hermano mayor) is set in Chenalhó, Chiapas. Bankilal is Manuel Jiménez, the most respected elder in his Tsotsil community. A gifted poet, his role is to provide spiritual guidance to the community, to intervene, on behalf of his community, with the forces that protect the universe and to pass on the ancestral customs and practices of the original Tsotsil forefathers and foremothers. His eloquence, however, does not convince younger generations. Many of them have little consideration for protective spirit animals, sacred mountains and other expressions of ancestral symbolism.

Bankilal (El hermano mayor) shows how elders have adapted to syncretic forms of worship since the introduction of Catholicism and how contemporary lifestyle is making their task an increasingly difficult balancing act.

Marina Abramović, Balkan Baroque, 1997 XLVII Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Attilio Maranzano

Shamans. Communicating the invisible. Exhibition view

at Palazzo delle Albere, Trento. Photo: Matteo De Stefano

Marina Abramović, aka the shaman of late capitalism, uses art as a ritualistic healing exercise akin to spiritual practices.

The performance she presented at the 1997 Art Biennial in Venice was a sort of shamanic ritual inspired by the ethnic cleansing that had taken place in the Balkans during the 1990s. Abramović vigorously scrubbed thousands of bloody cow bones over a period of four days. She later remembered the horrible smell rising in the hot Venice Spring and the impossibility of thoroughly cleaning all the blood from the bones. Blood can’t be washed from bones and hands, just as the war can’t be cleansed of shame. The images from the performance speak for the fratricidal war in Bosnia, but they also transcend it. They can be applied to any scene of violence in the world.

More images from the exhibition:

Bracha L. Ettinger, 7 Notebooks, 2017-2023. Shamans. Communicating the invisible. Exhibition view

at Palazzo delle Albere, Trento. Photo: Matteo De Stefano

Shamans. Communicating the invisible. Exhibition view

at Palazzo delle Albere, Trento. Photo: Matteo De Stefano

Shamans. Communicating the invisible. Exhibition view

at Palazzo delle Albere, Trento. Photo: Matteo De Stefano

David Aaron Angeli, Offerta della coppa piumata, 2023. Cellar Contemporary, Trento

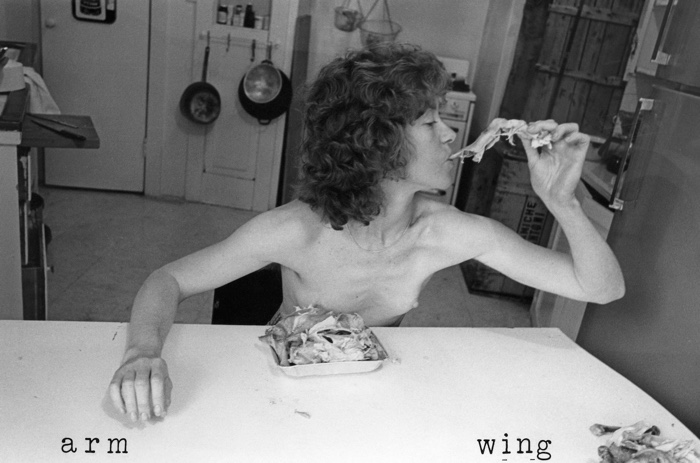

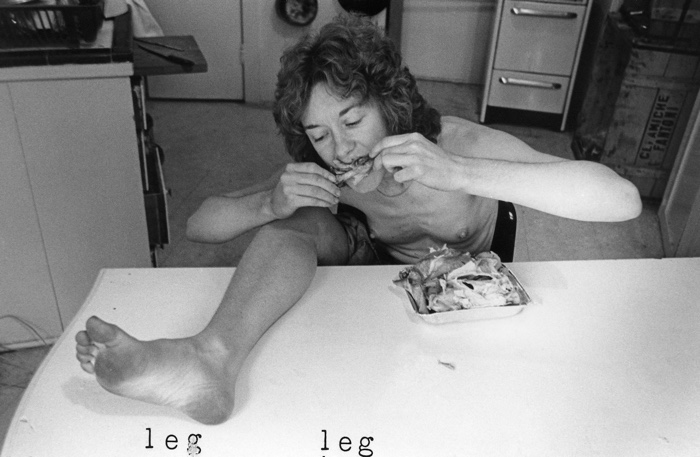

Suzanne Lacy, Anatomy Lesson #1: Chickens Coming Home to Roost (for Rose Mountain and Pauline), 1976-2005. Galleria Enrico Astun

Suzanne Lacy, Anatomy Lesson #1: Chickens Coming Home to Roost (for Rose Mountain and Pauline), 1976-2005. Galleria Enrico Astun

Shamans. Communicating the invisible. Exhibition view

at Palazzo delle Albere, Trento. Photo: Matteo De Stefano

Shamans. Communicating the invisible. Exhibition view

at Palazzo delle Albere, Trento. Photo: Matteo De Stefano

Shamans. Communicating the invisible. Exhibition view

at Palazzo delle Albere, Trento. Photo: Matteo De Stefano

Shamans. Communicating the invisible. Exhibition view

at Palazzo delle Albere, Trento. Photo: Matteo De Stefano

Shamans. Communicating the invisible. Exhibition view

at Palazzo delle Albere, Trento. Photo: Matteo De Stefano

The exhibition Shamans. Communicating the Invisible remains open at until 30 June 2024 at Palazzo delle Albere in Trento, Italy. Curated by MUSE – Science Museum of Trento as part of a wider cultural programme that brings together MUSE, MART – Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Trento and Rovereto and METS – Trentino Ethnographic Museum in San Michele all’Adige.

Previously: Dead White Men’s Clothes, Using art to study endangered indigenous rituals and music, The Occult, Witchcraft & Magic. An Illustrated History, Persona. Or how objects become human, etc.