Paul Granjon is a facetious French artist living in Wales. When he’s not performing wearing a flattering inflatable sumo suit, or organizing parades on Dutch market squares, Granjon builds robots using sausages, cadavers of parrot toys, heaps of fake fur and dolls. But behind the pop and quirkiness, the artist is investigating ‘the co-evolution of humans and machines’, inviting us to pause and reflect for a moment on our relationship with technology.

Paul Granjon is a facetious French artist living in Wales. When he’s not performing wearing a flattering inflatable sumo suit, or organizing parades on Dutch market squares, Granjon builds robots using sausages, cadavers of parrot toys, heaps of fake fur and dolls. But behind the pop and quirkiness, the artist is investigating ‘the co-evolution of humans and machines’, inviting us to pause and reflect for a moment on our relationship with technology.

Right now, Granjon has a solo show at the Oriel Davies gallery, in Newtown, Wales, where he is presenting Oriel Factory, ‘a radical new take on production lines.’ He gathered old computers, CD / DVD players, printers, toys, radios and other discarded machines and gave them as raw material to volunteers – the ‘Oriel Factory workers’. Together, they broke apart the ‘dead tech’ and, with the help of advanced home-manufacturing technology, re-composed and re-purposed them as robots and other artefacts for the gallery.

Image courtesy of Paul Granjon

Image courtesy of Paul Granjon

The exhibition forces awareness of the vast quantities of electronic waste produced by our early 21st century consumer society, and highlights the need for renewable energy. The exhibition also gently pokes fun at our fascination with, and endless appetite for new technology and the need to own the latest smart phone or the newest sat nav.

Image credit: Diana Gonçalves

Image credit: Diana Gonçalves

Chris Keenan made video documented the preparation of the exhibition, interviewed the participants and asked Paul Granjon to present his robots:

I talked to the artist as well:

What can gallery visitors expect to see in the gallery? Will the ‘production line’ still be operative? And will the public see projects that are already documented on your website or are they all new works that you have developed with the help of the volunteers using discarded electronics? Can you tell us something about some of these new works you created at the Oriel Factory?

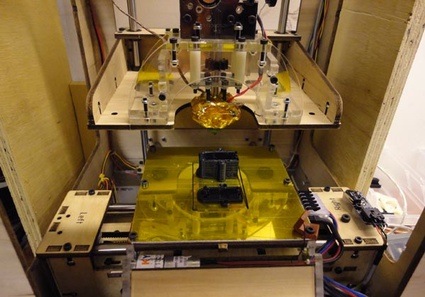

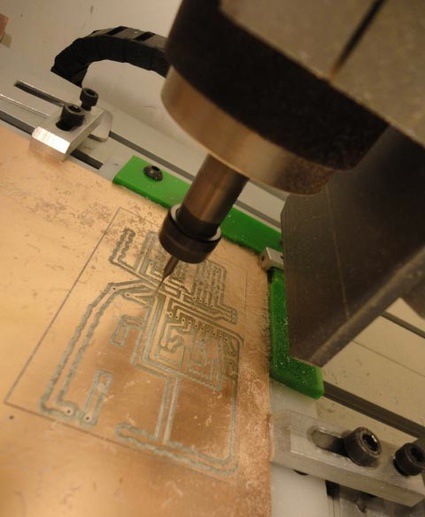

The Oriel Factory project splits the gallery in two main sections: the factory with operational production line, and the exhibition space. All the work in Oriel Factory is new. The idea was to build a set of mobile robots and to recruit volunteers to make contraptions for the robots from a large pile of electronic waste collected from the local council. Energy for the robots and their environment is provided by solar power and home-made bike generators. The robots and contraptions are visible in the exhibition space which they share with the visitors. There are 5 smaller robots, called the Thingies, whose bodies are made in metal recycled from old VCRs, combined with colourful perspex sheets cut on the factory’s CNC router. The Thingies move around, emitting sound from their built-in music boxes, and engage in simple interaction with the visitors. A larger robot called the Big Bootloader moves slowly on a taped track across the gallery. At times it opens its door and attempts to lure the Thingies inside with an infra-red beam and trap them in. A trapped Thingy will have to wait for the next opening of the door.

From 10th to 17th of September, visitors to the gallery could see the production line in operation. They could talk to the factory workers, have a look at work in progress, see the 3d printer in action and a play with the almost ready small robots. The show remains open until November 16th, with the factory left in the state it was for the opening. The robots are running, and several improvised contraptions made from recycled e-waste are activated in the exhibition space. The pedal generators that complement the solar panels which feed the robots can be used by visitors. A 20 minutes documentary film provides a comprehensive insight into the project all the way from early development stages to the opening. The film will be online at zprod.org as soon as the edit is finished, in the next few days.

Image credit: Diana Gonçalves

Image credit: Diana Gonçalves

On the one hand, you worked with old electronic kits. On the other one, you also used a 3D printer. Why did you need the 3D printer? Which objects or parts of objects did you shape with it?

On the one hand, you worked with old electronic kits. On the other one, you also used a 3D printer. Why did you need the 3D printer? Which objects or parts of objects did you shape with it?

The old electronics kits were used to make things that occupy the exhibition space, mostly simple kinetic pieces which can be triggered in sequence through a control panel made with an old Amstrad computer. The choice of using a 3D printer was an exploratory one, testing the little machine to see how useful it would be in a small scale production line.It ended up being used a lot in the robot-making process, the most visible 3D printed parts being the luminous tails of the robots. Other parts include motor and sensor holders, wheel hubs and whiskers mechanism, plus a couple of bespoke items printed for volunteers’ objects. I guess we got carried away a bit by the possibilities of the printer, and cut parts that would have been better made of metal: the wheel hubs are already showing signs of wear and I have to cut new ones in steel. But the tails are great!

Image courtesy of Paul Granjon

Image courtesy of Paul Granjon

The webpage of the exhibition explains that the work show “explores the possibilities offered by home-manufacturing equipment and the high-tech devices of tomorrow’s world.” Nowadays, we read about all these new, affordable tools to create our own objects,we can find any kind of DIY information and instructions for free online, should we have a question or problem we can get help in online forum, etc. Do you think that the number of people who are able to build and create their own tools, machines and objects is growing by the day or is building a small robot out of discarded material still something that only geeks do in their own backyard? Do you think that we will buy more manufactured stuff in the near future or will we make our own?

The webpage of the exhibition explains that the work show “explores the possibilities offered by home-manufacturing equipment and the high-tech devices of tomorrow’s world.” Nowadays, we read about all these new, affordable tools to create our own objects,we can find any kind of DIY information and instructions for free online, should we have a question or problem we can get help in online forum, etc. Do you think that the number of people who are able to build and create their own tools, machines and objects is growing by the day or is building a small robot out of discarded material still something that only geeks do in their own backyard? Do you think that we will buy more manufactured stuff in the near future or will we make our own?

I started “exploring the possibilities offered by home-manufacturing equipment” in spring 2011, when I bought a Thing-O-Matic and a small chinese CNC router. The learning curve was a bit steep and I had to call on my nerd fiber quite a lot in order to get results. With the 3D printer, the assembly takes more than 20 hours and involves soldering and precise tweaking. It would put some people off. That being said, once assembled the printer is straightforward to use and fairly reliable.

As for the future of such machines, I think they are already finding their way more and more into tinkerers’ sheds, educational institutions and small businesses. I am not sure how they will fit in homes, where their novelty value probably would not last long enough to justify the investment, and a trip to the local or online DIY shop will remain a simpler option for a while. Yet I can imagine doing an Oriel Factory-like project in ten-fifteen years time where we would find discarded 3d printers in the collection of electronic waste, in a similar way to the 2D printers we had for this event. An interesting side-effect of using a 3D printer is a minor invasion of defect ABS plastic prints. We were happy to give ours away to visiting school kids, but otherwise they could become a recycling problem…

Merci Paul!

Image courtesy of Paul Granjon

Image courtesy of Paul Granjon

I had to add the image of the Inflatable Suit:

The work of Paul Granjon remains on view at the on view at the Oriel Davies gallery in Newtown, Wales, until 16 November 2011.