I’m never not happy to visit the Venice Biennale. There are always a few works that make up for the overpriced food and the acrylic Michelangelo aprons sold by the Rialto. Wael Shawky’s Drama 1882 was the most astonishing, moving and beautiful video i’ve seen in a long, long time. Spain’s Pinacoteca Migrante and Portugal’s “creole garden” are two other highlights. Russia lent its pavilion to Bolivia, which led to much geopolitical speculation. Nearby, Israel’s pavilion was closed in an act of grandiloquent self-censorship and guarded by Italian soldiers. A genius marketing initiative that makes Israel look, again, like a victim. And I had not read reviews of the biennale before taking the train to Venice, so i didn’t realise that the German pavilion was not limited to the mound of dirt blocking its front entrance.

Claire Fontaine and Yinka Shonibare. Photo: Marco Zorzanello

What i couldn’t miss, obviously, was the main exhibition, titled Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere and curated by Adriano Pedrosa. The massive show talks about forced migrations, the stubborn influence of colonialism, climate (in)justice, exile, indigenous voices feeling like foreigners on their own land and more.

Here are the works that stayed in my head weeks after my return from Venice:

Karimah Ashadu, Machine Boys, 2024. Photo: Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

Karimah Ashadu, Machine Boys (trailer), 2024

Karimah Ashadu, Machine Boys, 2024. Photo: Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

Karimah Ashadu, Machine Boys, 2024. Photo: Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

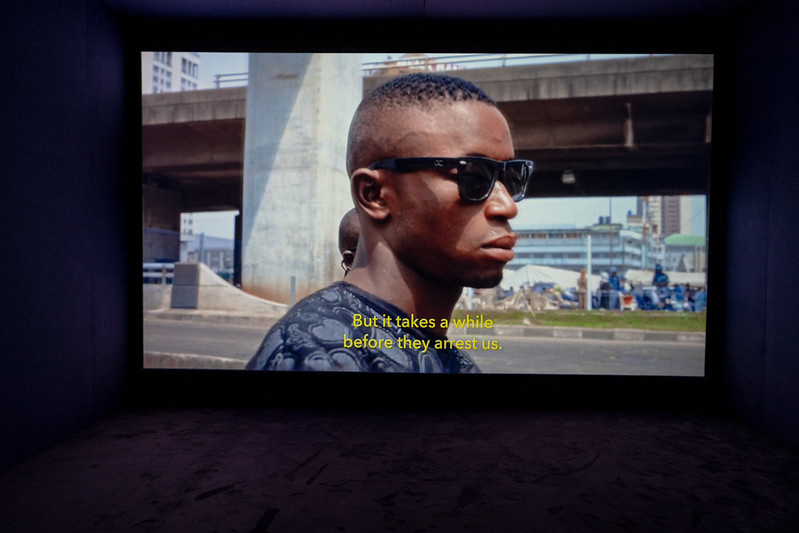

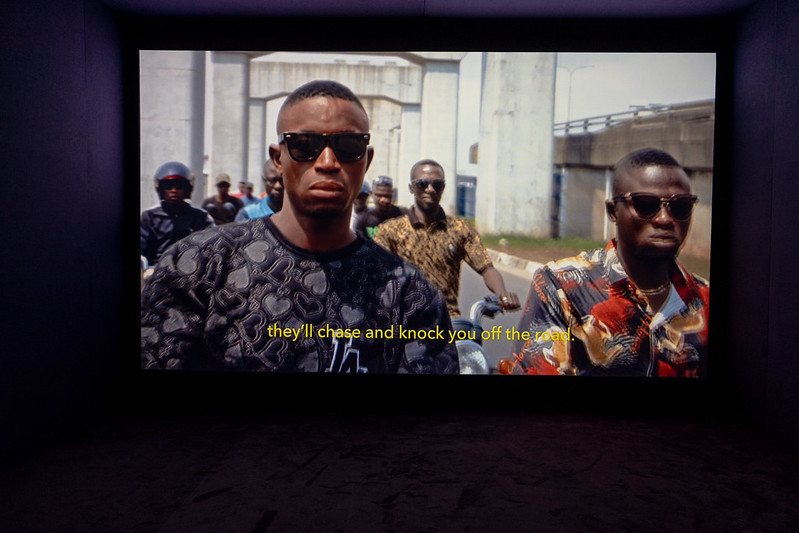

Karimah Ashadu, Machine Boys (film still), 2024

Karimah Ashadu, Machine Boys (film still), 2024

Karimah Ashadu, Wreath (Machine Boys), 2024. Photo: Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

In Nigeria and other African countries, an okada is an informal motorcycle taxi service that thrives where public transport is inadequate and where traffic congestion and poor road infrastructure reign. Okada has been associated with risky driving and accidents on the roads. As a result, okadas have come under heavy criticism, resulting in legislation intended to prohibit their operation in some Nigerian cities, notably Lagos. Unfortunately, the ban has made moving around the city more difficult for workers and students. It has also left many young people unemployed.

Karimah Ashadu‘s video Machine Boys portrays a group of bikers who flout the ban and engage in daily, testosterone-fuelled rituals on their bikes. They look powerful and fearless, but the film also shows their vulnerability: they perform dangerous moves on the bike while wearing only flip-flops and t-shirts; their situation is highly precarious; they are harassed by the police who confiscate and then ride their motorbikes; some dream of a better life (working as an okada until they have enough money to start their own business, for example.)

The filming is hectic, nervous and riveting. The camera seems to constantly find itself in the most unsafe places. In the middle of men revving up the engines, performing risky moves, throwing up thick veils of dust that shroud the screen.

“Through this exploration of Nigerian patriarchal ideals, Ashadu relates the performance of masculinity to the vulnerability of a precarious class of workers.”

Bouchra Khalili, The Mapping Journey Project, 2008-2011. Photo: Marco Zorzanello

Bouchra Khalili, The Mapping Journey Project, 2008-2011. Photo: Marco Zorzanello

Bouchra Khalili, The Constellations series, 2011

Biennale Arte 2024 – Bouchra Khalili

One long shot, one map, one hand with a marker. And that’s all The Mapping Journey Project, by Bouchra Khalili, needs to make us better understand what being an illegal migrant is.

Each of the eight videos details the story of one individual who has been forced by political and economic circumstances to travel illegally from the South of the Mediterranean to Europe. As their hands draw the perilous and convoluted routes across the Mediterranean, the invisible protagonists of the video tell about the anguish of hiding, moving towards the unknown, being arrested by the police and missing their loved ones. They never complain. They just share simple facts, always looking for a better place, waiting for papers, for money, for a lawyer, for a job or a place to sleep.

On one of the walls of the vast exhibition room, a series of silkscreen prints retrace the same routes in the form of constellations, recalling the ancient astrological knowledge that used to guide journeys and was rooted in mythological beliefs. The background of the prints is dark blue, like the night or like the sea. It is borderless, suggesting that boundaries are arbitrary and conceptions of nation-states unnatural.

“As with all of my works, the collaborators in the Mapping Journey Project are ‘civic poets’. In that sense, I don’t see them as migrants but as citizens whose civic rights and right to mobility are denied,” Khalili explained in an interview with KoozArch.

Fred Kuwornu, We Were Here: The Untold History of Black Africans in Renaissance Europe (trailer), 2024

Fred Kuwornu, We Were Here: The Untold History of Black Africans in Renaissance Europe, 2024. Photo: Matteo de Mayda. Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

Compared to the rest of Western Europe, immigration to Italy from other countries, especially from Africa, is a relatively recent phenomenon. Until the late 20th century, there were far more people emigrating from the country in search of work than people immigrating to Italy. Today, the ratio of immigrants/emigrants is roughly the same. Italian society is now trying to understand how to move from being discriminated against in places like Northern Europe or the USA to being the ones who have the responsibility of welcoming others. Sometimes reluctantly.

Fred Kudjo Kuwornu is an Italian Afro-descendant filmmaker and activist. We Were Here, his film at the Biennale, is part of a body of works that give visibility to the role that Afro-descendants have played in Western societies throughout history. We Were Here focuses on the history of art and the representation of Black Africans in European visual culture since the Renaissance. Through interviews with international historians, the artist challenges the notion that all Blacks were inconsequential slaves or servants. Not only were servants often entrusted with responsibilities but a fair number of Africans were princes, scholars, ambassadors, artists, soldiers and religious figures.

The documentary travels through Spain, Portugal, France, Italy, the Netherlands, the UK, Brazil, Ghana and the United States to make emerge the lives of the Africans who were in Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries. The film pieces together their origins, their role in society and their presence in the works of the most famous artists of the European’s Renaissance. Titian, Caravaggio, Velazquez and others. Many remain anonymous. The lives of others were better documented. The scholars interviewed by Kuwornu share the stories of Benedict the Moor, co-patron of the city of Palermo; Emanuele Ne Vunda, an ambassador from the Kingdom of Kongo to the Vatican and now buried in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome; Joao Panasco, a Portuguese knight of the military and religious Order of Santiago; the painter Juan De Pareja, an assistant of Diego Velazquez, whose paintings are part of the collections of major art institutions; the Latin professor Juan Latino, considered the first African who studied at a European university and who reached a professorship on Grammar and Latin Language at the University of Granada, etc. I was particularly interested to discover that Alessandro De’ Medici, the first Medici to rule Florence as a hereditary monarch, was rumoured to be the illegitimate son of Giulio de’ Medici (later Pope Clement VII) and Simonetta da Collavechio, a servant of the Medici household.

We Were Here: The Untold History of Black Africans in Renaissance Europe reveals overlooked figures and stories absent from mainstream historical accounts. I wish the film was screened all over Italy.

Joyce Joumaa, Memory Contours, 2024. Photo: Valentina Mori

Joyce Joumaa’s Memory Contours investigates the “intelligence” tests that immigrants were submitted to when they arrived at the Ellis Island processing station in New York in the early 1900s. Designed to identify “suspected mental defect”, the tests ensured that access U.S. citizenship was granted only to a “better class” of migrants and that “feeble-minded” people were turned away.

Joumaa replicates four drawings featured in the 1914 “US Public Health Service report Mentality of the Arriving Immigrant” and juxtaposes them with videos of hands recreating each sketch on a piece of paper. It’s shot from the perspective of the eye of the drawer.

The installation exposes the systemic suspicion towards who is foreign, different and deemed unsuitable. A century has passed since those abhorrent tests. The attitude of the USA and other Western countries towards migrants, however, is as cruel and discriminatory as it was then.

Ivan Argote, Paseo, 2022. Photo: Matteo de Mayda

In Paseo, Ivan Argote follows the three-meter-tall Columbus statue as it is removed from its pedestal on Madrid’s Plaza de Colón and towed through the capital. Passersby look baffled as the monument is unceremoniously driven through the streets.

This work is a decolonial fiction that imagines the moment when the coloniser will be stripped of honours and glory and paraded in the streets of Madrid toward his exile.

More works, no more words:

Brett Graham, Wastelands, 2024. Photo: Marco Zorzanello

Brett Graham, Wastelands, 2024. Photo: Marco Zorzanello

Santiago Yahuarcani. Photo: Andrea Avezzù

Santiago Yahuarcani. Photo: Andrea Avezzù

Marco Scotini, Disobedience Archive. Photo: Marco Zorzanello